Reading Lists

7 Books That Show Storytelling Has Consequences

Toby Lloyd, author of "Fervor," recommends novels and memoirs that reveal truths (or untruths) that were better left unsaid

There’s an old Talmudic injunction: “Your friend has a friend, and your friend’s friend has a friend; be discreet.” Living through a primitive age, when gossip was limited by oral transmission, the rabbinical sages feared loose talk—unkind words about neighbors, confessions of forbidden desire. Had those sages laid down one night and dreamed up modern publishing and the mass-market paperback, they might never have slept again.

In my novel Fervor, Hannah Rosenthal (like many writers) has no intention of being discreet; she aims to write and publish an account of her father-in-law’s experiences in the Warsaw Ghetto and Treblinka without his consent. That no one in her family wants her to proceed does not put her off. While she claims her motives are righteous—the old man is dying, she seeks to preserve his story from oblivion and honor the victims of the Shoah—money and fame also seem to twinkle somewhere on her inner horizon.

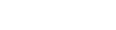

I have become interested in seeking out other novels where a character produces a “cursed book”—an object that reveals truths (or untruths) that were better left unsaid. These cursed tomes are sometimes memoirs, sometimes fictional, but are all bound by the same sense of breaking a taboo: no one stopped to think of their friend’s friend’s friend turning pages in the bath.

Different books enact different kinds of trespass, and the seven works on my list chart the range. Sometimes the demands of privacy are ignored and the doors to a heart’s sacred chamber are thrown open. Elsewhere a lie is dressed up and accepted as a truth, and a reputation is forever tarnished. Or the desire to write a great book, to seek out the most compelling literary material, is itself the motive for spurious deeds. Perhaps what fascinates most of all in these tales is the creeping fear that literature, despite good arguments made on its behalf, is inherently amoral—the author paring their nails behind the screen of words has always chosen not to care what damage their books will cause. Otherwise, they couldn’t write.

My Struggle: Volume 6 by Karl Ove Knausgaard

When the Norwegian author published the first volume of his autobiography, which draws its provocative title from Hitler’s prison memoir, he enacted a kind of Faustian pact. On the one hand, he became first a national then an international literary star; his books can be read in more than twenty languages, and the collection has been hailed as a masterpiece all over the world. On the other hand, My Struggle Volume 1 turned his own family against him. And it was precisely what made his autobiography so successful—minute descriptions of the ugliest parts of his own life, detailing his father’s abusive parenting style and eventual death from alcoholism—that also made it so painful to his nearest relatives. In Volume 6, Knausgaard wrestles with his conscience as he describes the events that led up to his own uncle suing him for libel and the even more devastating effects that his earlier memoirs have had on his wife’s precarious mental health.

The Vixen by Francine Prose

The place of storytellers in times of political turbulence has preoccupied Francine Prose since her first novel, Judah the Pious. In her most recent, The Vixen, it is not the writer of the cursed book whose morals are tested, but the cursed book’s unfortunate editor. In 1950s New York, at the height of McCarthy’s witch hunts, editorial assistant Simon Putnam is given the job of working on a trashy novel that demonizes the recently executed Ethel Rosenberg. Putnam is a Harvard-educated Jew who passes, almost without trying, for a gentile in a world where the memory of the Holocaust is everywhere, and where anti-Communist forces are weaponizing latent anti-Semitism throughout America. To complicate matters, the real Ethel Rosenberg was a friend of Putnam’s mother, and he knows that working on the novel that sullies her memory is both the perfect way to advance his career in the America that is taking shape around him and also a terrible sin.

Zuckerman Bound by Philip Roth

Like Prose, Roth was particularly energized by the ethics of writing Jewish stories in postwar America. This quartet of novels, written after he was catapulted to fame by Portnoy’s Complaint, chart the rise and fall of the novelist Nathan Zuckerman. In the beginning, Zuckerman is a writer in his twenties, enjoying the first flashes of literary success for short stories that offer intimate, sometimes unflattering portraits of Jewish characters. Already, he faces a backlash; certain Jewish authority figures accuse Zuckerman of recycling tropes that will provoke hatred of his people. As he embarks on his literary career, he has a choice. Will he do as he’s told by his father and his rabbi, and only write nice stories about nice Jewish families? Or will he continue down the road he’s started along, and pursue a darker form of artistic truth whatever the consequence?

Yellowface by R. F. Kuang

The morality of portraying a minority group in fiction also animates Kuang’s novel, Yellowface, though here the group in question is Asian Americans rather than Jews. And, crucially, the author who takes credit for having written the novel within a novel isn’t a member of the group. When Juniper Hayward steals her dead friend Athena Liu’s manuscript to edit and publish as her own novel, she tells herself she isn’t doing anything really wrong. The manuscript as Liu left it was in no fit state to publish, and she only means to give it the final polish required to let the book outlive its author. However, once she has started lying about the manuscript’s provenance, she finds herself heading rapidly down a track she cannot turn off. Soon, both June and Athena’s reputations are dragged through the mud, with accusations of colonial plundering and internalized racism thrown at each of them.

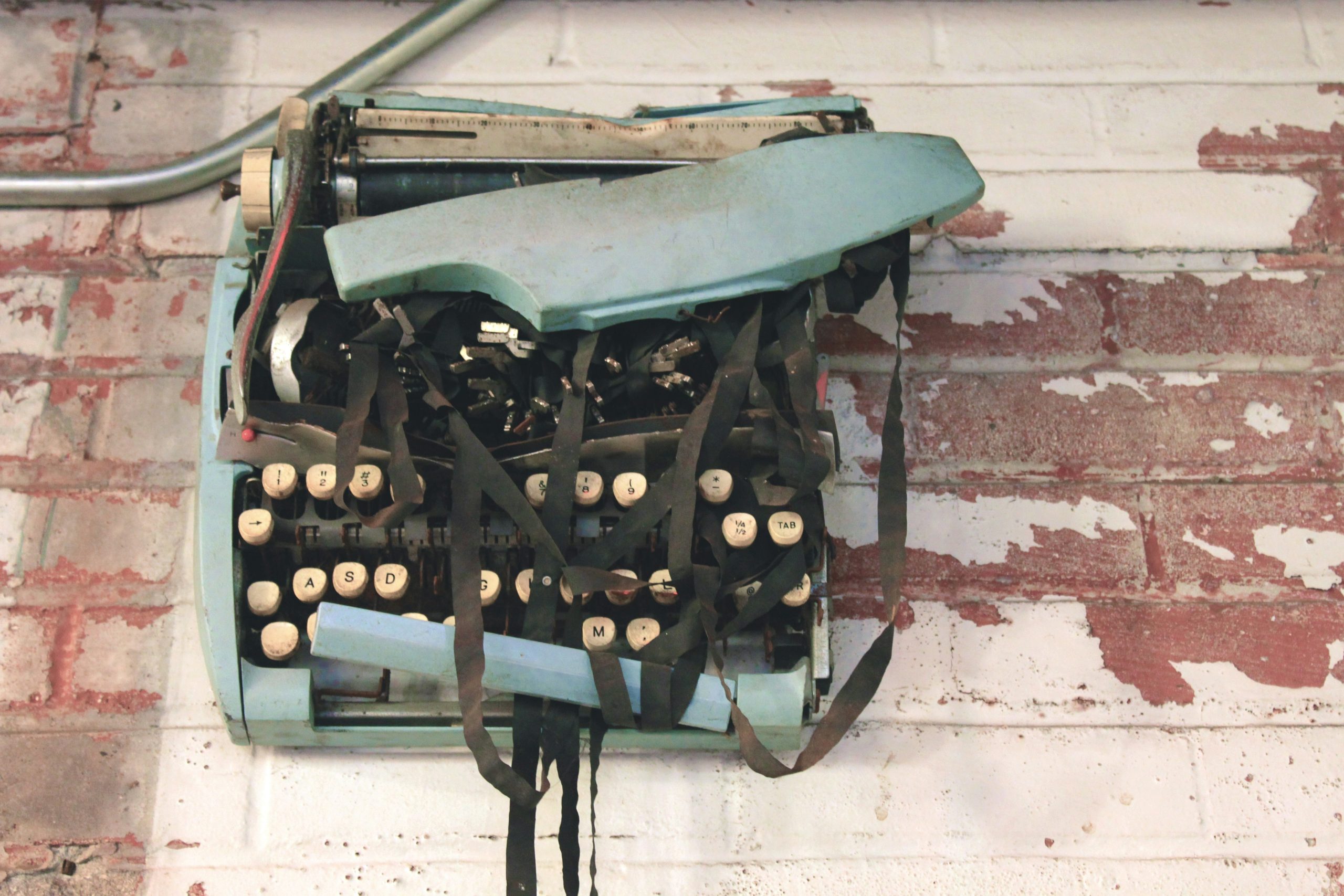

Man-Eating Typewriter by Richard Milward

Of course, not all cursed books are ushered into the world by mainstream publishing houses. In Richard Milward’s novel, a publisher of lowbrow and pornographic fiction, whose editorial director moonlights as a backstreet abortionist, agrees to print the manuscript of Raymond Novak’s memoirs as he sends it to them chapter by chapter in the countdown to what he promises will be a “fantabulosa crime” to shake the world. Is Novak full of hot air or is he a genuine violent criminal, a self-styled British Charles Manson? As the date of the crime approaches, and people start disappearing, we are haunted by the editor’s foreword, which warned us that although Raymond’s reign of terror started only with a paper cut, it led in time to wooden caskets.

Heir to the Glimmering World by Cynthia Ozick

Cynthia Ozick’s novel reveals the potential harms of stuffing a real person into fictional robes. The book follows the fortunes of the Mitwisser family, refugees from Hitler’s Europe, who come to depend on the patronage of James A’Bair. James, not unlike the real life Christopher Robin, is the son of a popular children’s writer who has written a series of novels about a character known as “the Bear Boy.” But while the character in the children’s book, adored in households on both sides of the Atlantic, lives an idyllic existence, suspended in a never-ending childhood, James, his real-life counterpart, has grown up and become helplessly embittered. For all the riches he inherited from his famous father, he seems bent on a course of self-destruction, threatening to ruin the happiness of the Mitwissers in the process.

The Book of Sand by Jorge Luis Borges

It would be remiss to compile a list such as this one without including at least one literal cursed book. In the eponymous story of this late collection by Borges, a man is visited by a traveling Bible salesman, who convinces him to buy a highly unusual piece: a book with an infinite number of pages. A page of this book, once seen, can never be found again. At first intrigued by this wondrous object, the narrator soon comes to see his new acquisition as monstrous. Mere possession of the book defiles its owner—he becomes reclusive and insomniac, haunted by nightmarish visions. Elsewhere in Borges’s collection, the danger of books is also evident. In one story, a misreading of scriptures leads a heterodox sect of Christianity into unthinkable sins, and in another an ancient poem written to praise a warrior king brings ruin to both the poet and his subject.