interviews

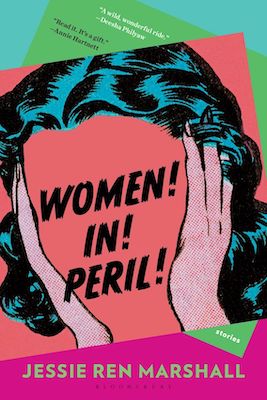

In “Women! In! Peril!,” Defying Societal Norms Is an Act of Reclamation

Jessie Ren Marshall on writing her debut short story collection and why she needed to leave New York to become a writer

Jessie Ren Marshall lives on an off-the-grid farm on Hawai’i Island. Women! In! Peril!, her irreverent stories are, as the title suggests, about women of various guises facing messy, precarious situations. This partial list of protagonists is a good indicator of Marshall’s amplitude: an Asian sex robot trying to outlast her return policy, a lesbian grappling with her wife’s “immaculate” pregnancy, a teacher lusting after a young student, a confused young American stripper in London, a Japanese freak show actress eager to escape her island. The formats vary too. She uses playscript, posts from social media accounts, and even journal updates from space.

While some stories are speculative and others realistic, each story plunges you into a deeply lived world where fucked up things—be it a toxic relationship, racial objectification, or climate doom—unravel in a way that is both bold and, often, hilarious. There is a guilty pleasure in reading these stories. You feel like you’re in the hands of someone who has a sharp eye for the strangeness of existing in today’s world and doesn’t have anything she is too afraid to say.

Marshall is an award-winning playwright and she spoke to me by phone from her farm about leaving New York to become a writer, claiming space, and the role of physical labor in her creative process.

Sasha Vasilyuk: There is a line in a story called Sister Fat that says “And you will be a perfect father. Being dead, you will not interfere.” What do you think is happening to women and feminism today?

Jessie Ren Marshall: Everybody should define feminism for themselves and think about what that means. I do think that this is a feminist book because unfortunately, at this stage of literature, it is still a radical act to show the point of view of characters who are not white men. Each story in this book explores a different woman’s point of view and within that, there is a lot of diversity because I think women aren’t just one thing and feminism isn’t just one thing. The act of claiming space and claiming your voice is going to be necessarily multitudinous and weird and unexpected.

In my writing in general, I am really drawn to women’s voices and women’s relationships. Part of that is because I can draw on my own experience and it’s just kind of a selfish thing to do. But at the same time, I do see it as an act of defiance against the norm. An act of inclusion. I really love stories about women’s relationships with women as well, not just their relationships with men or being defined by a romantic relationship because we’ve all seen that story a million times on Netflix. I’m really interested in exploring motherhood, particularly non-traditional kinds of mothering, or mother-child relationships. I myself am not a mother, but that doesn’t mean that I don’t have an understanding of that relationship. And sisterhood is a huge one for me. And then of course, there are also queer relationships between women.

SV: The collection has both speculative stories (a sex bot, a woman traveling to populate Planet B) and realist ones—a woman getting divorced, a teacher flirting with a male student, a strip club dancer in London, a reluctant teen piano player—that reading those I often found myself wondering what of your own past experiences had found a place on the page? Or do you try to keep yourself entirely out of your fiction?

JRM: I kind of love the framing of this question because I think there’s a little bit of a reluctance to say this fiction is based on my life, because then readers will want to find the answer. And the answer is not this really happened, whereas this other thing didn’t happen. It’s not a puzzle in that sense. It’s more that I have experiences and obsessions that then work themselves out on the page because I think I’m always seeking to address questions and to write around questions, but that doesn’t necessarily mean answering questions on the page.

For example, one of the more speculative stories, which is told from the point of view of a sex bot, is very personal to me and I think is one of the stories that is based more on my own life experiences than perhaps something that seems more realistic. The divorce story for example, I wasn’t going through a divorce. I hadn’t even met anybody yet. I was a lot younger, but the Annie 2 story [the opening story about the sex bot] was written during the anti-Asian violence that was happening, particularly in New York City. And it was a response to that feeling of helplessness that I had, being so far away from where I felt like the crux of the violence was happening. At the same time, even though I wasn’t there, I understood that violence in a deep sense, because I had experienced it in a million different small ways. I think that’s what happens with micro aggressions: they pile up, but if you point to any one individually, they don’t seem like a big deal. But the accumulative nature of racism and sexism is a violence that I think many Asian American women would recognize. In that story, even though it’s told in a humorous way and the reader is distanced from the narrator because we are not robots, it’s that play of narrative distance that I think is so interesting to explore and to reflect what it means to be human. So I hope that a human reading that story feels the gravitas of sexism, racism, othering, even though the story itself is more speculative in nature.

SV: Have you ever dreamt of a man sweeping you off your feet or coming to your rescue? Is it a dangerous narrative for girls to grow up with?

JRM: It is absolutely the baseline of what I grew up with. I think it is my generation’s baseline narrative of what you hope for as a young girl, and it is hard to escape. Any expectation for your life is going to be problematic. Anything that’s done by society is probably not going to work perfectly for anyone. But it is more complicated than just trying to work against this narrative of someone sweeping me off my feet, Princess Bride-style. It’s more complicated because there’s also this feminist counter narrative which was also shoved down our throats of “You need to save yourself. You need to be your own hero. Women are badass.” That is also problematic because it makes you feel wrong when you want someone to sweep you off your feet. What is wrong with wanting to be supported and saved and loved and adored? All of those things are part of human existence and I don’t think we should push them away as a kind of weakness. It’s all about balance, isn’t it? This is what being an adult is: we are trying to find a balance between what others want us to be and what we need to be in order to get through another day.

SV: What was it like coming of age as a writer in New York?

I do think that this is a feminist book because unfortunately, it is still a radical act to show the point of view of characters who are not white men.

JRM: What I said before about having to navigate the trench between the way the outside world sees you and what you need in order to survive another day. That definitely applies to being a writer in New York. There was a lot of anxiety of influence that I felt when I was there, particularly in terms of the literary scene. At that time, which was a while ago, the literary world was so based in New York City, the American publishing world was not as diffuse as it is today. It felt like everyone in my MFA program was reading the same stories in the New Yorker, the Atlantic, Harper’s. We were being fed the same books and we had similar goals because what you read is kind of what you end up wanting to write. I really enjoyed the social aspect of the MFA program, but at the same time, I don’t think it was the best place to develop as a writer because of that anxiety of influence that I felt. So I overcorrected and moved to Hawaii. And that became a really amazing place to settle into my voice more deeply, and figure out what I wanted to write about or what I was interested in. Because I didn’t think about what was being published in the New Yorker that week.

SV: You live with your dogs off the grid on a remote farm on Hawai’i Island. It’s a dream of many a writer, but the reality of very, very few. What does it do to your brain to be away from society?

JRM: You’re right in that it is a very romantic notion that in order to be an artist, one has to remove oneself from society and be alone. I mean, everyone from Thoreau to Andrew Bird has said that it is a helpful thing to do. Andrew Bird, the musician, I think it was one of his earlier albums, where he just went to a cabin in the middle of the woods and knocked it out himself. There is something about the idea of being totally in your own created world that is very appealing, especially for a fiction writer because you don’t need other people to create that world. It’s a self-sufficient space. I think also being in nature is incredibly helpful for the creative process. It allows me to remind myself that I am a part of something larger than myself. And since I’m not religious, I think I need to find that reminder somewhere else and it comes from the natural world for me. In terms of not being a part of society, that has been quite difficult. I am a hermit by nature, I enjoy being alone, I don’t often long for company. But society is more than people. There is an aspect of society that I really miss, which is cultural connection, going to the theater, going to a restaurant, seeing what new things other people who are creative are creating. It’s sad to be apart from that for most of my days. And at the same time I do think one of the most wonderful things about having a book published is that it connects you to so many people in your work in public.

When your work becomes public, it’s like you’ve debuted into society. That’s actually a wonderful side effect that I wasn’t aware of is that I’m connected to all these people that I might not have met if my work weren’t becoming public soon. It is hard to be not in a city. I think when your book comes out there’s some anxiety that I feel because I would prefer it if I could have that permanent sense of community around me, of literary community, of creative community, friends and family, but at the same time, that’s what writing retreats are for.

SV: You’re working both on your farm and on your novel, Alohaland. What role does physical labor play in your creative process?

Being an adult is trying to find a balance between what others want us to be and what we need to be in order to get through another day.

JRM: I try to spend a portion of every day doing something that is either working on the land or working on the house and both of those are definitely works in progress. I have a burgeoning garden, I build fences, I build furniture. I’m trying to make the world a little bit better, the world inside my space bubble. I’m trying to improve things and I think that that can be really useful as a writer because you spend so much time in your head creating a fake physical world. It’s nice to return to the actual physical world, where objects have permanence that you can touch and lift and move.

I think there are a lot of helpful parallels to when you look at the way that things grow and things decay and things die. There is a cycle of life to, particularly, the gardening and observing the land that keeps things in perspective. When you’re creating something like a book, which seems permanent, it seems like an object, but really everything is impermanent, because that’s just the cycle of time. So let’s not get too attached to the things that we make.

SV: Do you ever feel like a woman in peril?

JRM: I mean, I do get hurt sometimes, physically. So in those times, I think that I do curse the fact that I’m alone and trying to do things myself, but I also really like the self-sufficiency of knowing that I can lift really heavy things and, although it’s challenging, I can prevail. I think that has made the act of writing a book seem a little bit less daunting, because it is hard. It’s so fucking hard to write a book! It takes so much perseverance, it takes so much faith in yourself. And the way you build a fence is bit by bit. You don’t build it all in one day, especially when you’re doing it yourself without a lot of large tools to help you. But if you’re doing it with your own two hands, then it happens slowly and that’s the same way a book gets written.