Reading Lists

10 Feminist Retellings of Mythology

Christine Hume, author of "Saturation Project," recommends modern stories that turn patriarchal folklore on its head

Truth be told, I loathe re-imaginings of myths. The impulse feels reformist rather than revolutionary. I find these renderings on the whole stale and striving, hubristically clever, empty adaptations overly attached to their sources. They trip over their own longing for narrative’s initial hit of euphoria or devastation and slip misty-eyed into nostalgia. Maybe that makes my list invalid, or maybe that makes the books on it exceptional, which they all are.

With that out of the way, I’ll start all over. At the end of story-telling is myth-making: exhausted, stripped down narrative, pure grammar crystalized into affect. And when it’s good, it’s very-very good, a risk with the added danger of feeling safe. Myth-structure holds the power to awaken us to our own history and also to make ourselves into strangers. In Saturation Project, I adopted myth in the first section as a way of finding a repressed girlhood. The story of Atalanta, broken and re-set askew in tiny cages of self-conscious self-mythologizing, led me into my own memory and located a specialized knowledge that accommodated both unruly wildernesses and intense interiorities.

Though my book is memoir, fiction immediately comes to mind for the epic task of feminist re-mythologizing. Margaret Atwood, Pat Barker, Madeline Miller, Sarah Ruhl, Natalie Haynes, and Emily Hauser, for instance, all retell the Trojan War from the perspective of the women in the background. Hashtag we love to see it. Moving in and out of myth though offers writers a little more room to play and to surprise.

Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward

I exchanged letters last year with a writer incarcerated in Texas (through Deb Olin Unferth’s marvelous PenCity Writers Program) about Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward. He was especially vivid at accounting for the way Ward uses fractured and recombinant myth (ancient Greek, biblical, American South) to pick up narrative speed.

“Triptych: Texas Pool Party” in Triple Canopy Magazine by Namwali Serpell

My students in a text image class gravitated to a breath-taking moment in Namwali Serpell’s “Triptych: Texas Pool Party” that adopts the Perseus myth briefly to economize the narrative. The piece—a three-part fictional re-telling of news story captured on video of a Texas pool party in which a white police officer assaulted a 15-year-old Black girl in 2015—shifts point of view midway, pivots into heroic rhetoric, its tyrannies and fallacies, to reveal the real monsters in our midst (despite the grand jury declining to indict the offending officer).

Antígona González by Sara Uribe, translated by John Pluecker

Two weeks before the end of 2020, I listened, rapt, to a bilingual choral zoom reading of Sara Uribe’s Antígona González by Rosa Alcalá, Susan Briante, giovanni singleton, Carmen Giménez Smith, and Anna Maria Hong. Antigone is already feminist, but this updating of her story concentrates thousands and decades of missing bodies, missing family and friends, in Mexico into a singular grief, a singular search and standing before the law. I rely on communal contexts because they signal conversation like a counterpunch that explodes into a contrapuntal extended dance remix. In other words, these books, equal parts inventive and disruptive, aim to take back patriarchy’s tools in order to dismantle its house (versioning Audre Lorde, an autopoetic myth-maker herself).

Under Everything by Daisy Johnson

Daisy Johnson’s Under Everything hijacks the Oedipus cycle with fairy tale riffs and fingerings. Her Jocasta-figure steps from the shadows into a visceral presence; her Oedipus is trans. The novel’s gorgeous prose immerses us in fluidity—gender, sexuality, memory, language—yet that very mutability, its queer, abolitionist currents, determines “everything” eternally.

Fablesque by Anna Maria Hong

All of Anna Maria Hong’s books feature fabulous feminist retellings—I name her Queen and King of the genre! —that disenchant narrative form as a vector of cultural myths. Her latest, Fablesque, features détournementsof Siren, Ouranus, and Kronos, from the Greco-Roman tradition, along with fairy tale and fable refigurations. This book and her sharp, animist Age of Glass share a poetic interest in mythological beasts, human monsters, and mutated half-gods with Donika Kelly’s delicious debut Bestiary, marvelously questioning the shapes our identities take.

For Her Dark Skin by Percival Everett

For Her Dark Skin, Percival Everett’s satirical treatment of the Medea myth adopts a common enough idea, that myth is always related to questions of origins: how, why, and what things are the way they are, but renders it terrifyingly hilarious and cruel. When Everett turns this idea on gender and race, he refers us back to our linguistic and narrative frames, which become an endlessly reductive and recycled fate. We live in myth/language because it lives in us. If I’m making it seem more like an argument than a joyride that unexpectedly overtakes us, I’m Deadalus wrong.

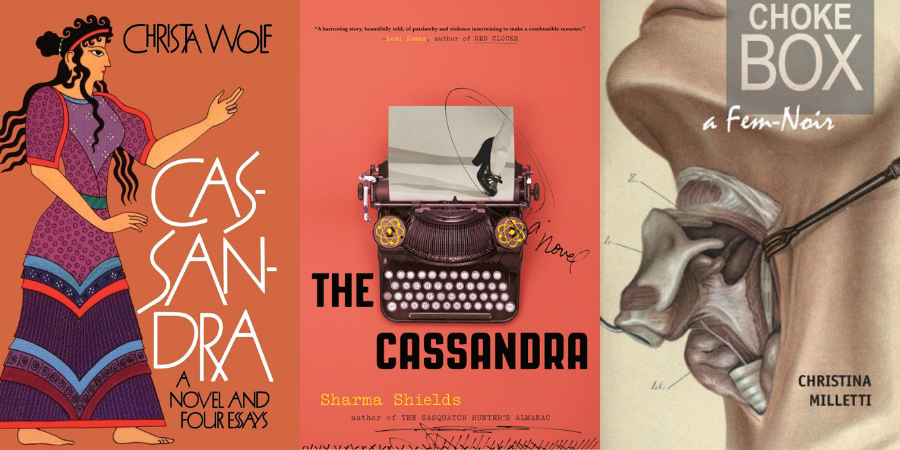

Cassandra by Christa Wolf, The Cassandra by Sharma Shields, and Choke-Box: A Fem-Noir by Christina Milletti

While the re-activation of specific myths gathers tension in the distance between the contemporary world and the ancient one, the opposite is also true, often simultaneously. Christa Wolf, Sharma Shields, and Christina Milletti give the best voice to Cassandra, whose story seems especially resonant right now. Cassandra prefigures our current gaslighter-zeitgeist and instantly imbues it with tragedy. Women, especially Black women, are mocked, belittled, and ignored for speaking the truth—about sexual violence, racism, the climate crisis, and the pandemic. Sharma and Wolf focus their warnings on the industrial military complex. Milletti’s Choke Box: A Fem-Noir is a more subtle, inter-textual retelling than Wolf’s Cassandra: A Novel and Four Essays and Sheilds’ The Cassandra. And Milletti catches us in half-complicity, stuck between sympathy and judgment. We question both the Cassandra-figure’s reliability as a narrator and the over-confidence of male authority, undermining her at every turn.

Trail of Lightning by Rebecca Roanhorse

If climate catastrophe is our present and apocalypse is our future, Rebecca Roanhorse’s Trail of Lightning makes vivid that the end of the world is also our colonial past, where America’s beginning was the Dinétah’s (traditional homeland of the Navajo tribe) demise. In this heart-racing, Navajo-myth-meets-urban-post-apocalyptic-fantasy, however, the badass protagonist makes clear “This wasn’t our end. This was our rebirth.”