Lit Mags

The School

A short story by Donald Barthelme, recommended by Steven Polansky

Introduction by Steven Polansky

In the Fall of 1972, I enrolled in the Ph.D. program in English at SUNY Buffalo, where I spent one anarchic year — in the Student Union I accidently stepped on a couple copulating on the floor — then fled.

I’d come to Buffalo hoping to work with John Barth, a luminary there, and a leading figure in American post-modernist fiction. (I couldn’t have told you then, in any satisfactory way, what “post-modernist” meant.) When I applied, I didn’t know that Barth had decided to leave Buffalo for Johns Hopkins (via Boston University). I went to Buffalo expecting Barth, and got Barthelme, whose post-modernist light was not a watt less luminous.

In each of my two semesters at Buffalo, I took a graduate fiction writing seminar with Barthelme. In each seminar I produced two stories. For me an impressive output never to be repeated. All four of my stories were futile, sycophantic travesties of stories in Barthelme’s collection, City Life, then all the rage. I wanted Barthelme to like my work, and me, but I could not tell what he thought of either. In class and out, Barthelme was courtly but aloof, and I wasn’t ever sure he knew my name. I was not clever or sophisticated enough, not free enough in spirit and imagination, insufficiently steeped in world literature and music and, especially, in the visual arts, even to approach the kind of arch and high-gloss and often brilliant literary maneuvers of which Barthelme was master.

I’d read half a dozen of Barthelme’s stories in The New Yorker. I didn’t understand them, could not have explicated those texts for love or money. But I admired their brittle, ironic surface, and Barthelme’s wit and manifest refinement. Since leaving Buffalo I’ve read most of his work, and with, perhaps, a bit more comprehension.

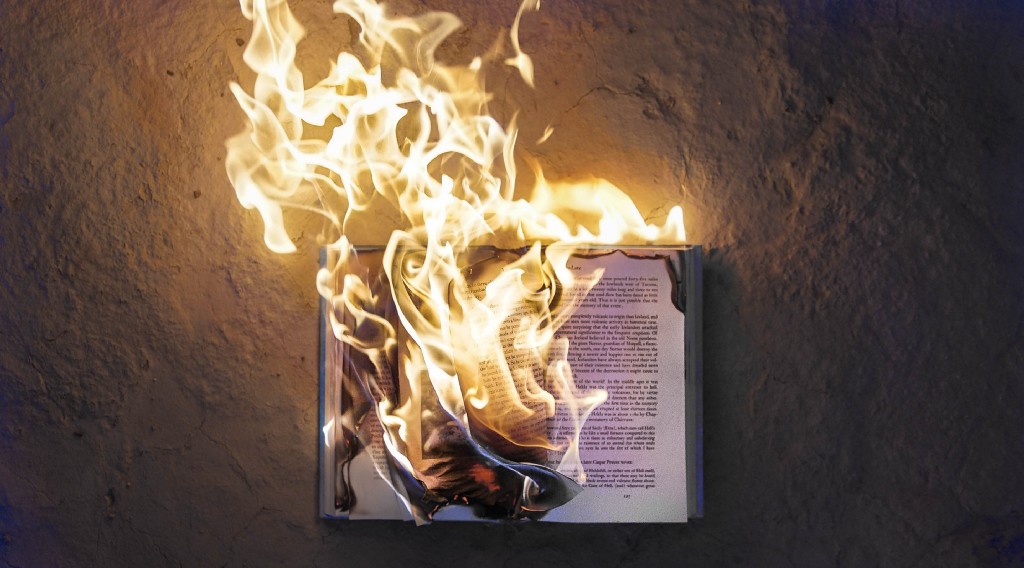

Barthelme’s short fiction is unapologetically difficult. In a 1987 essay, “Not-Knowing,” Barthelme writes: “Art is not difficult because it wishes to be difficult, rather because it wishes to be art. However much the writer might long to be straightforward, these virtues are no longer available to him. He discovers that in being simple, honest, straightforward, nothing much happens.”

Barthelme published some 70 stories in The New Yorker. Other writers have held a comparable sway over that magazine’s short fiction empire — Irwin Shaw, John O’Hara, John Cheever, J.D. Salinger (despite his relatively meager output), John Updike, Mavis Gallant, Alice Munro — all of them writers of “straightforward” fiction. All of them susceptible of imitation, however pallid. Barthelme is inimitable, sui generis — in this way, like Borges — his universe of discourse his alone. For an aspirant, such as I was, nothing to be learned, except the crucial stuff: discipline, authority, audacity, and a scrupulous precision.

When I knew him, Barthelme was in his early forties. He died in 1989, at the age of 58. “The School,” which appeared first in the 1976 collection, Amateurs, is one of Barthelme’s more accessible stories. To describe it is to sound ridiculous: a very funny story about death and the negation of meaning, and the only story ever written, by anyone, in which a resurrected gerbil is the bringer of hope.

–Steven Polansky

Author of Dating Miss Universe: Nine Stories

The School

Donald Barthelme

Share article

“The School” by Donald Barthelme

Well, we had all these children out planting trees, see, because we figured that… that was part of their education, to see how, you know, the root systems… and also the sense of responsibility, taking care of things, being individually responsible. You know what I mean. And the trees all died. They were orange trees. I don’t know why they died, they just died. Something wrong with the soil possibly or maybe the stuff we got from the nursery wasn’t the best. We complained about it. So we’ve got thirty kids there, each kid had his or her own little tree to plant and we’ve got these thirty dead trees. All these kids looking at these little brown sticks, it was depressing.

It wouldn’t have been so bad except that just a couple of weeks before the thing with the trees, the snakes all died. But I think that the snakes — well, the reason that the snakes kicked off was that… you remember, the boiler was shut off for four days because of the strike, and that was explicable. It was something you could explain to the kids because of the strike. I mean, none of their parents would let them cross the picket line and they knew there was a strike going on and what it meant. So when things got started up again and we found the snakes they weren’t too disturbed.

With the herb gardens it was probably a case of overwatering, and at least now they know not to overwater. The children were very conscientious with the herb gardens and some of them probably… you know, slipped them a little extra water when we weren’t looking. Or maybe… well, I don’t like to think about sabotage, although it did occur to us. I mean, it was something that crossed our minds. We were thinking that way probably because before that the gerbils had died, and the white mice had died, and the salamander… well, now they know not to carry them around in plastic bags.

Of course we expected the tropical fish to die, that was no surprise. Those numbers, you look at them crooked and they’re belly-up on the surface. But the lesson plan called for a tropical fish input at that point, there was nothing we could do, it happens every year, you just have to hurry past it.

We weren’t even supposed to have a puppy.

We weren’t even supposed to have one, it was just a puppy the Murdoch girl found under a Gristede’s truck one day and she was afraid the truck would run over it when the driver had finished making his delivery, so she stuck it in her knapsack and brought it to the school with her. So we had this puppy. As soon as I saw the puppy I thought, Oh Christ, I bet it will live for about two weeks and then… And that’s what it did. It wasn’t supposed to be in the classroom at all, there’s some kind of regulation about it, but you can’t tell them they can’t have a puppy when the puppy is already there, right in front of them, running around on the floor and yap yap yapping. They named it Edgar — that is, they named it after me. They had a lot of fun running after it and yelling, “Here, Edgar! Nice Edgar!” Then they’d laugh like hell. They enjoyed the ambiguity. I enjoyed it myself. I don’t mind being kidded. They made a little house for it in the supply closet and all that. I don’t know what it died of. Distemper, I guess. It probably hadn’t had any shots. I got it out of there before the kids got to school. I checked the supply closet each morning, routinely, because I knew what was going to happen. I gave it to the custodian.

And then there was this Korean orphan that the class adopted through the Help the Children program, all the kids brought in a quarter a month, that was the idea. It was an unfortunate thing, the kid’s name was Kim and maybe we adopted him too late or something. The cause of death was not stated in the letter we got, they suggested we adopt another child instead and sent us some interesting case histories, but we didn’t have the heart. The class took it pretty hard, they began (I think, nobody ever said anything to me directly) to feel that maybe there was something wrong with the school. But I don’t think there’s anything wrong with the school, particularly, I’ve seen better and I’ve seen worse. It was just a run of bad luck. We had an extraordinary number of parents passing away, for instance. There were I think two heart attacks and two suicides, one drowning, and four killed together in a car accident. One stroke. And we had the usual heavy mortality rate among the grandparents, or maybe it was heavier this year, it seemed so. And finally the tragedy.

The tragedy occurred when Matthew Wein and Tony Mavrogordo were playing over where they’re excavating for the new federal office building. There were all these big wooden beams stacked, you know, at the edge of the excavation. There’s a court case coming out of that, the parents are claiming that the beams were poorly stacked. I don’t know what’s true and what’s not. It’s been a strange year.

I forgot to mention Billy Brandt’s father who was knifed fatally when he grappled with a masked intruder in his home.

One day, we had a discussion in class. They asked me, where did they go? The trees, the salamander, the tropical fish, Edgar, the poppas and mommas, Matthew and Tony, where did they go? And I said, I don’t know, I don’t know. And they said, who knows? and I said, nobody knows. And they said, is death that which gives meaning to life? And I said no, life is that which gives meaning to life. Then they said, but isn’t death, considered as a fundamental datum, the means by which the taken-for-granted mundanity of the everyday may be transcended in the direction of —

I said, yes, maybe.

They said, we don’t like it.

I said, that’s sound.

They said, it’s a bloody shame!

I said, it is.

They said, will you make love now with Helen (our teaching assistant) so that we can see how it is done? We know you like Helen.

I do like Helen but I said that I would not.

We’ve heard so much about it, they said, but we’ve never seen it.

I said I would be fired and that it was never, or almost never, done as a demonstration. Helen looked out of the window.

They said, please, please make love with Helen, we require an assertion of value, we are frightened.

I said that they shouldn’t be frightened (although I am often frightened) and that there was value everywhere. Helen came and embraced me. I kissed her a few times on the brow. We held each other. The children were excited. Then there was a knock on the door, I opened the door, and the new gerbil walked in. The children cheered wildly.