essays

His Life Was Saved by Rock and Roll

An Interview with Jeff Jackson

When Jeff Jackson and I met at an artist’s colony this past summer, we bonded over our mutual obsessions with cults, captivity narratives, and rock and roll. One of Jeff’s characters is enslaved in his new book, Mira Corpora, while Unreformed, my teenage boot camp captivity narrative, explores my stint at an evangelical Christian reform school. Later we were thrilled to discover that in 2008 we attended the same Vic Chesnutt show.

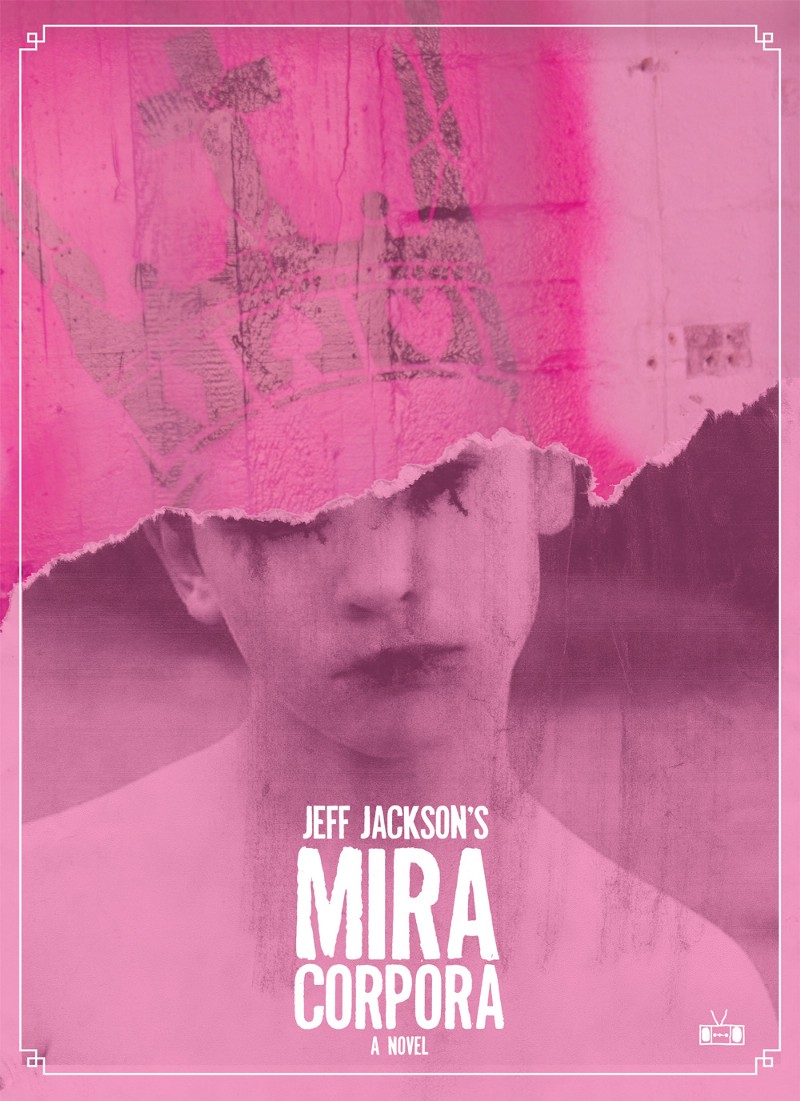

Initially Jeff was shy about sharing Mira Corpora’s galley, but once I convinced him to share, I tore through it in less than twenty-four hours. I was ensnared by its strange beauty, entranced by a world in which feral children roam through abandoned theme parks haunted by gibbons, where teenage oracles reign over a dead village, where punk rockers stalk a mysterious rock star. Don DeLillo found “its manic pacing and summoning of certain cultural emblems” mesmerizing, as did I. Recently, Jeff and I discussed Mira Corpora online.

The author’s note claims “this novel is based on the journals I kept growing up.” You’ve created a distinctive voice for your narrator. Did it really emerge from actual journals? How reliable is this narrator?

The narrator’s voice definitely started with re-reading these real childhood journals that I’d been carrying around forever. They were full of memories, gossip, odd daydreams, local myths. Enough time had passed that I realized there was material I could mine from them. The voice that came out was different from anything I’d previously written and the journals were the springboard.

In terms of the narrator’s reliability, he’s trying his best to accurately relay his impressions but there are gaps in his memories and some encounters create severe confusion. I wanted to honor his confusion and represent it as honestly as possible. The narrator’s sometimes unsure how to read and feel about certain situations, and the reader should be as well. As a result, the story is pitched between various recognizable emotional states, styles, and even genres. There’s a tangible reality in the novel, but there’s also a little bit of dream logic at play.

Your narrator, Jeff, is dying from gangrene poisoning when he is befriended by a wealthy European socialite, Gert-Jan, who after nursing him to health feeds him drugs and enslaves him. At one point he uses Jeff as a party prop. The whole section reminded me of a conversation we had about cults and how their leaders prey on the weak. Did your interest in cults and behavior control help you create Gert-Jan?

I’ve always found cults fascinating and tend to see them as a more concentrated form of society.

To me, they’re a sort of microcosm for understanding some of the sickness, pathology, and the control that can play out unnoticed in more subtle ways in our everyday lives. And in the case of a few communes, they also represent possible paths for a better society.

I’m not sure my understanding of cults had too much to do with the character of Gert-Jan though. He’s more of a lone wolf and not someone who’s trying to form a group around his personality. He’s focused on exploiting one individual at a time. My understanding of his psychology was based partly on various con artists and sociopaths I’ve run across. These people are more common than we want to believe!

When Jeff was Gert-Jan’s captive, he replicated trauma, experienced dissociative states, had suicidal ideations, and later felt pangs of regret for betraying his captor. It felt authentic. How were you able to immerse yourself so deeply into this mindset?

Mainly, it was where the story needed to go. I drew on myself and people I knew — plus my imagination. That said, I’ve found personal experience isn’t a shortcut to making something come alive on the page. It’s hard to animate these sorts of experiences with words and I experimented a lot to find the right combinations of tone and point of view.

The biggest challenge was making sure readers didn’t get desensitized.

We read about unthinkable tragedies every day and it’s an instinctive reaction to shut them out.

I tried to include shifts in perspective, odd moments of beauty and tenderness, and unexpected realizations that hopefully keep you engaged. I also tried to allow readers the space to have their own reactions and hopefully empathize.

I really didn’t want this section to read like victim literature. Richard Wright says he knew he failed when his novel Uncle Tom’s Children made readers cry — because it gave them a catharsis that was too easy and ultimately trivialized the issues he was addressing. Genuine empathy needs to be active, something you have to work to achieve — as a human being and a reader.

Many of Mira Corpora’s characters exemplify man at his most feral: abusive mothers, drunken would-be saviors, half-mad heroes, policemen blinded to those who need the most help. And much of the novel is set within landscapes corroded with rot and decay. Does this reflect your view of modern society?

Certainly civility seems to be breaking down to an alarming degree and our technological advances are aimed more at 140 characters than addressing our crumbling infrastructure. But Mira Corpora hopefully exists — at least partly — outside of the moment of “right now.”

One reason for the feral behavior is that I was trying to get past the social niceties and dig beneath the skin of the story. I wanted to evoke something rawer that represented the essence of the characters and their situations. As for all the rot and decay, I have to confess that some industrial wastelands with their rusting bridges and half-cobbled streets strike me as gorgeous. Partly, I set scenes in these landscapes because of their sheer beauty.

The novel is set in a time before cell phones and internet, a time of cassette tapes, walkmans, and phone booths. Why did you choose to set this novel then?

I didn’t want Mira Corpora to be set in a specific year. There’s a dreaminess to the tone that I hope extends to the time period. I also think the fastest way to date something can be to include a lot of technology and pop culture references. That stuff changes at lightning speed these days. Plus there were plot practicalities: My narrator couldn’t afford a cell phone and wouldn’t have many people to call anyway. As for cassette tapes, they’re great totemic objects. Creating a personalized mix tape and decorating it for the recipient can often feel like a private ritual. Cassettes also have a grubby physicality that seemed more appropriate than vinyl, CDs, and certainly MP3s. It’s interesting to see how they’re making a comeback in indie circles.

You’ve had five plays produced in New York City. Have your experiences as a playwright helped you develop character?

It’s strange to say, but my playwriting experience has taught me almost nothing about character! My plays exist somewhere between traditional theater and performance art. It’s taught me a lot about thinking visually, collaging different tones, layering story elements, and creating situations where performers can thrive. But I’m not often delving deeply into character or psychology.

Character was much more important for Mira Corpora. I needed to know the character’s motives and psychology at every step, even when they weren’t sure themselves. These things aren’t always on the surface, but I tried to embed them into the text.

As a rock and roll chick, I was especially attracted to Lena with her “ratty locks (that) almost seem like an apology for her delicate and classically beautiful features.” She seems to know everyone and is fearless about reaching out to others for help, which clues you into her privileged background. These suspicions are confirmed when we learn her “squat” is actually an apartment she inherited from “some relative or another.” How did your life in the punk scene help you create these characters?

If you’ve spent any time around any punk scene, there’s almost always a few people who are slumming. They come from serious money but feel it’s more “authentic” to act like they’re poor. Pulp’s song “Common People” does a great job of dissecting this cultural phenomenon.

Lena is one of these people, but hopefully that’s not her defining characteristic. She’s also very kind and passionate about music. She romanticizes the narrator’s poverty in a way that’s a bit naïve and condescending, but she’s also young and still figuring things out. She’s mixed up like the rest of us and the narrator really likes her despite her put-ons. He’s got too many worries to indulge in the luxury of worrying about so-called authenticity, anyhow.

Jeff joins Lena’s search for Kin Mersey, the mysterious singer who dropped off the radar after releasing an unforgettable album with “tales of drunken fathers too scared to commit suicide, mute twins in white dresses spilling their parents’ ashes over a frothing ocean, dead girlfriends reincarnated as black swans, or blue orchids, or flaming pianos.” Did you have any real-life inspiration for Kin Mersey?

I drew on a bunch of different people for Kin’s character and then heavily embellished with my imagination. One of the inspirations was Jeff Mangum. His music has this tremendous emotional power. I was also fascinated by the extreme fan reactions after he disbanded Neutral Milk Hotel. For a while, there were websites and message boards with wild rumors about why he quit and what he was doing. I remember one thread proposing fans build him a treehouse city where he could work on new material in private. Almost all these sites have vanished now, but their obsession was really touching. In some ways, I was inspired by people’s intense attachment to Jeff Mangum’s music as much as the music itself. I should probably emphasize here that I don’t know Jeff at all, though I’m glad to see him out there making music again. Some people have told me they find the ending of Kin Mersey’s section to be incredibly negative, but I think there are a couple of different ways to interpret that situation. Kin’s solution to his problems is very different from any of his real-life inspirations.

You begin your first chapter with a quote from The Mekons. Later, when Jeff makes a break from a bad circumstance, he only carries a few belongings, including “my cassettes of favorite songs taped off the radio.” Music propels the narrative throughout. Why is music important to Jeff? What implications does this have on the book as a whole?

Music is a life raft for the narrator — same as it was for me growing up — and keeps him afloat during grim times.

Songs seem like they hold secret messages just for him. Discovering Kin Mersey’s music offers dizzying glimmers of a better world and new possibilities.

I really wanted Mira Corpora as a whole to have the power of a great rock song. Something with a visceral kick you can feel in your body, strong emotions that are swaddled in distortion, and that rushes past a little faster than you can keep up. I love music that overwhelms and slightly confuses me on first listen, leaving me to dust myself off and figure out exactly what I just heard. I love music that’s immersive. The best way to understand it is to hit repeat.