interviews

Hurt People Hurt People: An Interview with Roxane Gay

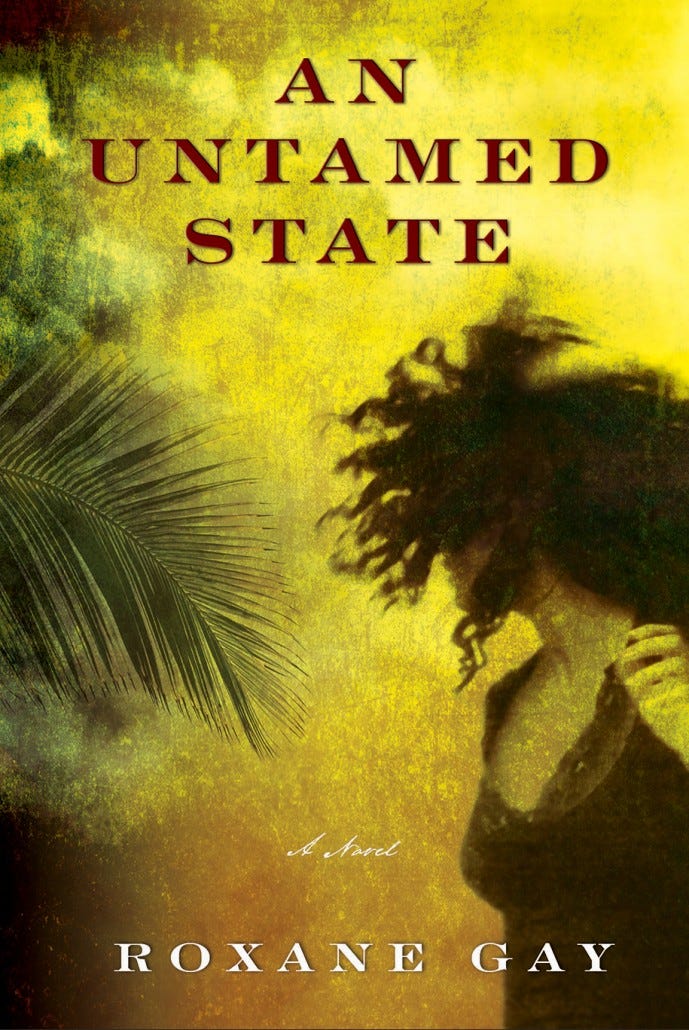

Mirielle Duval Jameson’s fairy tale life is shattered when, during a visit to Haiti, she is kidnapped. Her father, a self-made millionaire, refuses to pay the ransom. Infuriated, her captors take their revenge on Mirielle, brutalizing her past the limits of what she previously thought possible to endure. After her release, she struggles to come to grips with her father’s betrayal, with her punctured illusions of Haiti, and with reconciling who she is now with the woman she was before.

Roxane Gay’s debut novel, An Untamed State, is her second work of fiction; Ayiti, a short story and poetry collection, was released in 2011. An anthology of Gay’s essays, Bad Feminist, will be published in August. Over the past few weeks, Gay and I discussed the link between inequity and violence, its impact upon women, and the books that most challenged her.

Early in An Untamed State, Mirielle notes that “There are three Haitis — the country Americans know and the country Haitians know and the country I thought I knew.” Can you discuss the Haiti Mirielle knows? How does it compare to the Haiti you know?

Before her kidnapping, Mireille only knows a life of privilege both in the States and in Haiti. By way of her father’s success and her family’s social standing, she has been afforded every opportunity and though she isn’t spoiled she has taken a lot for granted. During and after her kidnapping, she begins to see so much of what she has, unwittingly, turned a blind eye to, circumstances that drive people to consider kidnapping a viable option.

The Haiti I know is definitely closer to the one Mireille knows before her kidnapping — one where I have had the opportunity to see the best of the country and her people, though certainly not with the same extravagance. To be clear, my novel is fiction. That said, I have always been mindful of how lucky I am as a Haitian American. As I got older, my eyes were certainly opened to the poverty far too many people in the country experience. I began to realize my family and I enjoyed a lifestyle few others were afforded and I’ve struggled with what to make of that.

Mirielle is brutalized horrifically by her captors. Why did you choose to explore this topic?

Kidnapping is a brutal crime, and certainly, what happens in An Untamed State is intense but I wanted to go there. I wanted to imagine what it would be like for Mireille to not only be kidnapped, but also suffer her father’s betrayal because that, too my mind, is the truly insurmountable trauma. There is, indeed, a lot of violence in this book but the world is a violent place and all too often, women are the victims of that violence. This does not mean that violence defines women’s lives. In this novel, violence is a symptom of a much more profound malaise.

Can you elaborate on how violence is a symptom of a more profound malaise? How is this related to inequity?

There are situations, like absolute poverty, where you feel so helpless, so unable to even conceive of how to change your circumstance, that all you can do is lash out. All you can do is give physical voice to your rage. In this novel, that is, in part, what motivates the kidnappers.

Mirielle’s father Sebastien cannot bear to allow the men who kidnapped his daughter take everything he has struggled to build. His denial of what could happen fractures his daughter so brutally that she has to forget who she is in order to survive. This ties into another theme — the price that daughters have to pay for the dreams and delusions of their fathers. Can you elaborate?

Sebastien, like the kidnappers, is also, in his way, a victim of circumstance. The poverty of his childhood has scarred him in the way that makes it possible to wait too long to secure his daughter’s freedom.

I think children often pay the price for their parents’ dreams and delusions. In this novel, it is, in part, a father’s choices that profoundly change the course of Miri’s life. I was interested in that, how the person who was supposed to have her best interest in heart, prioritized his own best interests instead.

There are also so many other fathers who have contributed to the circumstances that give rise to a place where people consider kidnapping a viable choice. I hope I acknowledged that in the writing.

During a craft talk at Atlanta’s Lost in the Letters Festival you said, “I’m a slow burner. I’ve been writing a long time.” How has time helped you develop your craft?

I’ve been writing since I was four years old. I’ve been publishing since the late 90s. It’s only in the past four or five years that I’ve been meeting with any kind of success.

Taking time has allowed me to become a much better writer and reader. I learned how to more rigorously edit myself. I mostly got over the phase of my writing life where I thought everything I wrote was perfection. Basically, I grew up and certainly I have a lot of growing yet to do.

During that same talk you encouraged writers to “read diversely in every single way, to challenge yourselves, to read outside of your comfort zone.” What books have challenged you? What would you include on your recommended reading list?

Books that have challenged me include Story of O, Deliverance, We the Animals, Notes From No Man’s Land, Maidenhead, everything Percival Everett writes… the list is long and continually evolving. I recommend reading all those books and the complete works of Zadie Smith, Meg Wolitzer, James Salter, Edith Wharton, Tayari Jones, Birds of a Lesser Paradise by Megan Mayhew Bergman, The Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward, and The Lover by Marguerite Duras.