interviews

How Women Prop Up the White Nationalist Movement

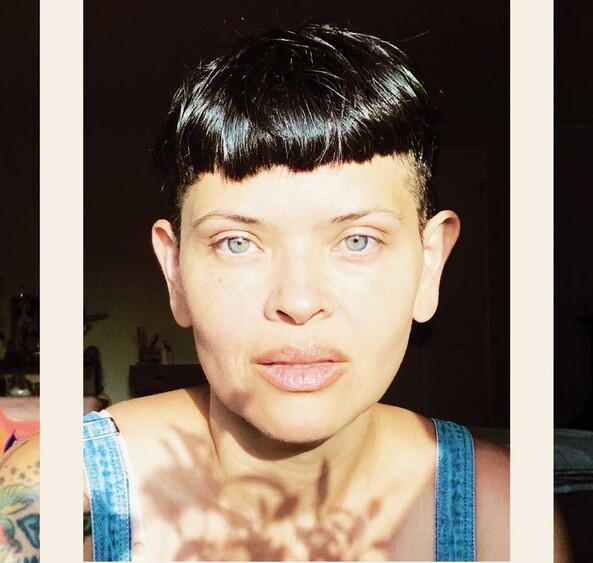

Seyward Darby, author of "Sisters in Hate," on white identity, Black Lives Matter, and racial justice

Seyward Darby’s Sisters in Hate: American Women on the Front Lines of White Nationalism opens with the author witnessing another white woman screaming a racial slur at a Black woman at a gas station in the Shenandoah Valley. Darby describes the Black woman’s face as revealing “only mild surprise—or maybe it was practiced defense.” In conversation, Darby is quick to note that she had no idea what the woman was going through internally, that this was all the woman was choosing to reveal, but Darby herself was caught off guard. When I asked Darby about her reaction, she described feeling complicated, the way she felt in the aftermath of the 2016 election, when “so many white people were surprised with the outcome, but anybody from a different perspective, particularly anyone who was Black, was not. I was surprised that I didn’t feel surprised,” Darby said. “I realized I had buried my understanding of race and what I had grown up around. When I wasn’t as surprised as other people,” she said, “I wondered what I had been ignoring.”

In Sisters in Hate, Darby profiles Corinna Olsen, Ayla Stewart, and Lana Lokteff, three women associated with the modern white nationalist movement, a sub-group often overlooked by the mainstream media. She explores their motivations for joining the movement, how they use their platforms to exploit the grievances and fears shared by a growing number of white Americans, and highlights the abuses the women are subjected to in this highly gendered environment. Along the way Darby traces the ties of the modern white nationalist movement to earlier hate movements such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the Third Reich, and Neo-Nazism, examining the connections between the far-right, white Christian evangelicals, paganism, and mainstream liberalism.

Darby and I spoke in early August on a day when America felt like it was literally unraveling—165,000 Americans, disproportionately Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous, have died from Covid-19, the protests for racial justice sparked by the murder of George Floyd are continuing, the economy is in free fall. Darby and I both identify as white. We discussed how white women have historically exercised power, how the far-right distorts demands for racial justice to provoke backlash, and what we can do to dismantle white supremacy.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: How have your views on whiteness changed over the course of writing this book?

Whiteness as an identity is a measure of power and of privilege as much as it is one of appearance, so even if I didn’t feel like I was white in any conscious way, I was benefitting from the identity constantly.

Seyward Darby: Growing up, if somebody asked me to list five things that described me, whiteness would not have been one of them. In the course of working on this book, I realized that whiteness as an identity is a measure of power and a measure of privilege as much as it is one of appearance, so even if I didn’t feel like I was white in any conscious way, I was benefitting from the identity constantly. My research also very much clarified for me what whiteness isn’t. It isn’t defined by the same things that define Black identity or any number of other identities. There’s not a white culture or clearly shared white heritage. Who counts as white has changed dramatically over time. Whiteness is a constructed category at the top of the social hierarchy, accessible only to some.

I think that what the far right does, what white nationalists do, is they try to make whiteness into this coherent cultural identity. They are perfectly aware that it is a measure of power, but they don’t want to talk about it like that. They need it to be a definition of self and community that is at once more neutral and more tribal, something people can rally around and that critics can’t easily target.

That’s frightening. Ashley Jardina, a political scientist who studies whiteness, has found that a substantial percentage of white Americans are now identifying as part of a racial group and that they are not satisfied with the group’s status. She’s quick to say that a person who sees themselves as part of a white community isn’t necessarily bigoted, but here’s the thing: if there is a concretizing sense of white identity as demographics change in the United States, the far-right may well exploit it.

DS: In Sisters in Hate, you follow three women from the modern white nationalist movement, but you also follow how white nationalism has operated historically, highlighting the work of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Can you briefly trace how the UDC served to reinforce white supremacy?

SB: When you think about hate in America, the first thing that comes to mind is the KKK. That was a fraternal association when it was founded in the 1870s. No women were allowed at that point. White women were symbols, they were what the KKK was fighting for, what they were claiming they were trying to protect—the purity of the white woman, and by extension America as a white nation.

At the same time, the UDC was organizing, and by the turn of the century, there were chapters everywhere. They were the soft power to the Klan’s hard power. The KKK was a terrorist organization that was lynching people, whipping people, doing horrible things. The UDC was sipping tea, talking about how can we erect monuments to the Confederacy? How can we demand that textbooks be edited to share this halcyon idea of the antebellum period? With the KKK, we can look at them and say they did terrible things, but with the UDC it’s more complicated because they were not breaking any laws. Their work is a side of the perpetuation of white supremacy that we don’t talk about as much, the part that’s more deeply ingrained in our everyday lives—what we see memorialized in the streets, what we read in books, how we understand the country’s history. It’s still an organization that people are involved in today.

This is the thing about hate: there are the very obvious crimes and slurs, the stuff that is so abhorrent, but there’s also the quiet and frankly more impactful work of writing narratives about what America is, what it should be, what history has been like. And I think that women have been crucial whitewashers.

DS: Definitely! They whitewashed white supremacy into heritage. What I love about this book is that you show us the history. Why is it important to trace the throughline between Reconstruction and now?

SD: People who are part of the far-right, particularly the digital neo-fascists of today, will try and separate themselves from the past. They’ll say they’re not in the KKK, they’re not neo-Nazis. They’re just asking people to see the truth about an anti-white agenda, to rebel against what they see as a too-liberal mainstream. They are trying to make themselves into prophets but if you actually look at what they believe, it’s the same old garbage. That’s why the history is so important: it lets us hear the echoes and put the lie to what white nationalists today try to claim.

The other reason I wanted to trace the history is because whenever that history has been traced by journalists or scholars, everybody talks about these male figureheads, these idealogues, and women are just a footnote. I didn’t want to place George Lincoln Rockwell or Nathan Bedford Forrest or David Duke at the forefront. I wanted to highlight the work that women have done and to show the ways it’s still very similar to the work that women do today. In some ways, it’s almost a feminist approach to history, though what’s strange is I am trying to shine a light on people who are anti-feminist—giving anti-feminists a feminist treatment.

White nationalism is all about exercising and negotiating power. I remember early in my research I was speaking to Kathleen Belew who wrote Bring the War Home, about white nationalism in the post-Vietnam era. She told me that to understand how women have power in this space, you have to relocate and redefine what power is. If you just think who is the president of an organization, who is committing the violence, who is the face of an ideology, women are not going to seem that powerful. But if you think of power in a more intimate sense—in homes, communities, relationships—suddenly women hold a lot more. Thinking about activism in a more multifaceted way allows us to see women more completely in the movement. A handful of feminist historians have done that to an extent. I wanted to bring their work together and apply my own research.

DS: White nationalism is inherently sexist. It treats motherhood as the cornerstone of its racial project. You trace this historically to the Nazi cult of motherhood. Why is white nationalism appealing to white women?

SD: I think that the appeal for white women today is that you are promised value and power simply by virtue of being physically who you are, a woman who looks a certain way and can have children. You are necessary to the future of the white race because of your aesthetics and biology and voice. You are literally being told that you are empowered without having to do much of anything. That can be alluring to some people.

The appeal for white women today is that you are promised value and power simply by virtue of being physically who you are, a woman who looks a certain way and can have children.

It’s a hyper-sexist space, but there are women I studied who weren’t finding their place elsewhere, who were disenchanted with other communities they’d been a part of, more feminist ones. White nationalism offered them a platform.

There is a certain level of mental gymnastics involved in being a woman in this space. On the one hand, supporters claim that men of the far-right love and respect women and just want the best for them, but what “best” means is remarkably antifeminist and misogynist. The far-right does not remotely define women’s interest in any way that I would define them.

They are coming to the table with completely different terms of the conversation, defining words in different ways, believing falsehoods. You cannot apply your way of seeing the world to their way of seeing the world. If you told a woman on the far-right that she was fighting against her own interests, she would likely say, “But my interests are the patriarchy, my interests are traditional gender roles, my interests are protecting my race.”

One of the tricky things about covering white nationalism is being able to see the world through white supremacists’ eyes, so that you can better grasp their motivations and aims. But you also have to be able to articulate why their way of seeing is unethical. You can’t just say that they have their worldview and you have yours and each is valid because frankly, that is exactly what they want outsiders to say. They want that to be the response from people who are covering them. But you also don’t get very far if you dismiss their worldview out of hand as idiotic or cruel and thus not worthy of serious analysis. Too often in history, unethical, fringe viewpoints have been treated that way, and so people are shocked when they gain traction. Understanding something doesn’t mean condoning it. You can understand something and still call it abominable.

DS: Can you talk about how the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Eric Garner awakened the far right?

SD: People talk about how Trump was so important as a catalyst, but the seeds existed before his candidacy in 2015-2016. Trayvon Martin was killed in 2012. When Dylann Roof murdered 9 people in Charleston in 2015, he pointed to the reaction to Martin’s death as the key awakening that he had. #BlackLivesMatter as a hashtag and a movement formed after George Zimmerman’s acquittal, but even before that Trayvon Martin had become this touchstone for Black and progressive activists. Later we saw protests in the streets after Michael Brown’s killing and Eric Garner’s killing. The chatter on the far-right was very much in the vein of “this is what we have been worried about. This is what we should have been planning for.” Black Lives Matter in the minds of the far right had to be—still has to be—anti-white lives. That myth became a rallying cry, an organizing kind of tool. It was the conspiracy theory of “white genocide” for the new millennium.

At the same time BLM was finding its footing and becoming the most important social movement of the last 25 years, the far-right was taking fuel from it in a different way. Backlash was forming. Dylann Roof is the ultimate example, but as Lana Lokteff, one of the women in my book, said, “2012 was a big year.” Why? Trayvon Martin was killed in 2012, and we started having this national conversation about police brutality, and then we started talking about the dignity of Black lives, so that by the summer of 2014, when Lokteff started to use her platform to go hard in a white nationalist direction, she was citing as all these cultural trends that would not have existed without the rise of a new kind of civil rights movement.

I hate to be such a downer about the present moment because in terms of the activism this summer and people taking to the streets and demanding justice in such a nuanced way—it’s not just about police brutality, it’s also about supporting communities—that’s all just so deeply exciting. But at the same time, I think there will be backlash. There will be fuel for the far-right. They are already saying things like “we’ve been telling you that Black lives means anti-white.” I’m not saying this is going to lead to a Dylann Roof style massacre, but from an ideological perspective demands for racial justice are something white nationalists can use to play on white people’s fears and uncertainties about the present moment.

DS: In Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements, Charlene Carruthers writes:

“White rage in the face of college-aged people wearing polo shirts and khakis makes liberals fearful. They are fearful because the country they thought they knew is not only slipping away; they realize that it never truly existed.”

How do people get past the fear and recognize that white nationalism is as you wrote “a crisis of individual and collective responsibility”?

SD: I’m so hesitant to be prescriptive because I don’t think that I have any great answers, but I do think that the first step is realizing that we never had a post-racial America. Black scholars, artists, and activists have been saying this for so long—from James Baldwin to Ibram X Kendi to Nikole Hannah-Jones—insisting that we recalibrate what we mean when we talk about American ideals. In practice, they have been so exclusionary. Equality for some. Liberty for some. If we don’t acknowledge that and work from a place of truth, people are going to make the same mistakes and fall for the same tropes.

DS: You write that women are the hate movement’s “dulcet voices and its standard bearers.” Given that white women have historically supported white supremacy, do you think that women who consider themselves white should play a particular role in dismantling white supremacy?

SD: Absolutely. I think that women have such an important role. White women are uniquely placed to recognize the mythologizing, the whitewashing, that far-right women engage in—seeing it for what it is and not letting people get away from it under the auspices of “we are just nice white women.” Also, white women who are not white nationalists can have an impact by recognizing the ways in which their own choices might play into structures of white supremacy and making new ones, better ones, more just ones. Certainly, this is where the podcast Nice White Parents and conversations about opportunity hoarding are important. The least white women can do is look at the ways in which our individual choices and actions play into structures that very much need dismantling.

The other important thing, as a white woman engaging in racial justice work of any kind, at any scale, is recognizing that you are going to say the wrong things. You are going to say things that don’t come off the way that you mean. You’re going to say things based on incomplete information or biases. Frankly you are going to fail sometimes, but if you want to be a real supporter of a better, more just future you can’t run away from the hard stuff, say “I can’t handle it.” That’s why one of the quotes at the beginning of my book is from Samuel Beckett, “Try again. Fail Again. Fail better.” To me that is a mantra almost. You’re not going to play the perfect part in dismantling white supremacy. That’s not the point, because it’s not about you in the first place. Certainly, in my own life, I’m trying to walk the walk.

DS: That’s part of doing the work.

SD: Right? And listening more. Knowing where you can contribute. People ask why did you pick this topic for a book? There are any number of reasons, one of which is that it was something I had unique access to as a white woman. I could spend time in this space in a way that maybe other people who don’t look like me couldn’t. I could interrogate my own life experience as I went. I was trying to approach the conversation about race and hate in America from the standpoint of what—as a white woman—was in my lane, as opposed to veering into someone else’s lane. That’s the work I think.