interviews

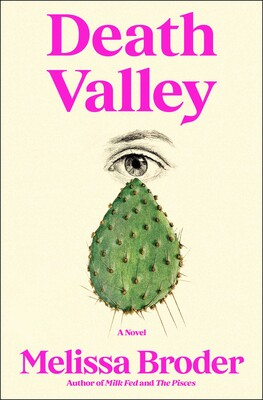

In Melissa Broder’s New Novel, Grief Looks a Lot Like a Cactus

The author of "Death Valley" discusses getting lost, learning from her characters, and the beauty of Best Westerns

“It’s brave of us to die!” writes Melissa Broder in Death Valley, a desert survival story. The woman in Broder’s third very funny novel, like Broder’s other characters, is recognizable by her need to “control the uncontrollable,” as well as her wit, occasional panic, deep and unrelenting introspection, and love affair with Best Westerns (“Where the wood can be fake, make it fake. Where linoleum can be used, use linoleum. If a geometric shape can be incorporated into any wall, rug or floor tile, it’s going in”).

The woman’s father has recently come out of a coma after a very close call, and no one can say how much time he has left; her husband is nine years into a debilitating condition that becomes inescapable for both of them. “I love you,” something the woman says multiple times a day, “can mean anything from I’m sorry you’re suffering to Please stop talking.” She escapes to the desert, she believes, to finish her novel. In actuality, she is here to reckon with her own powerlessness and unlikely resilience. On an ill-advised hike through the desert, the woman stumbles upon a strange cactus—a cactus can be a portal and “every door can be a trap door”—and is met both with her father when he was young and her own unexpected feelings about seeing him in such a childish state. Then, when she thinks she is ready to go home, she goes back to the desert and really gets lost. No food, no water, no bars on her cell, not a soul who knows where she is or that she is hurt.

The reader might feel they are wandering the desert with heat stroke before heat stroke actually sets in: rocks talk, rabbits have a party—and then things get weird. There is an obvious metaphor here about how times of grief are days spent wandering a desert—except there is nothing obvious about Broder’s searching, or the tenderness she visits on characters who fail to save those they love from pain and death, not even able to give them hotdogs when they ask for hotdogs. Seek and ye shall seek becomes a refrain in the novel, and a portal that leads to a higher self.

Annie Liontas: How would the protagonist in Death Valley define courage?

Melissa Broder: I think she thinks that courage is something that comes naturally to a person, that it’s an inborn trait rather than something that we need to muster or a resource that can come out of weakness or out of fear. I would say that she does not believe she is courageous, she does not believe that she has strength. She believes those who are not fearful don’t need courage. She doesn’t want to be having to face what she is facing. She doesn’t want her husband to be sick. She doesn’t want her father to be in the ICU. She doesn’t want to be lost in the desert. I think she’s a very fearful person, and yet there’s a will there. On some level, it’s about acceptance and seeing.

AL: So it seems like courage is something she feels is beyond her, at least in the beginning?

MB: She is forced to discover that she has inner resources in order to survive. She’s not a wilderness-y person, but she knows how to do things. I read some desert survival manuals in writing this book, so she actually knows to do things I would have never known to do. For example, looking to see what animals eat. There’s that moment where she’s going to eat one of the wild flowers and is surprised by the thought “Oh, I must really want to live.” And that parallels her father, who always seemed kind of “meh” about life until he’s in the ICU and really wants to live. By the end of the book, courage is a resource that she summoned. And she’s surprised by the will and surprised by her own fortitude.

AL: The novel—and the character—makes sure that she is very quickly stranded in the high desert. Why was this isolation essential for her awakening?

MB: It would have been a totally different book if she’d been stranded with others. But I was actually very conscious of that isolation when I was writing the book. I didn’t want to write a COVID narrative, but my father was in the ICU during COVID and the first couple of months we weren’t allowed to go see him. My dad had been in an accident in December of 2020, and he died in May 2021. We would FaceTime my dad every day, and sometimes he was conscious, and sometimes he wasn’t and the nurse would just put the phone on his pillow. And so, for me, the book could not have been another way. I needed to create that isolation for her. It’s in part about all the ways that we find connection, even in isolation. It can happen with the earth or with the rocks or with the rabbits. In a way, her isolation brings her closer to others.

AL: How is loss as much a portal as the cactus?

Grief brings a depth to life and a connection with the sacred when we face it.

MB: I see loss and grief as very akin to being lost in the desert. It can seem endless. We’re not in control. Nature or the nature of the emotional landscape is in control. We have to keep going, but there’s also a certain degree of surrender to the elements. We can’t fight against it. A desert animal is nocturnal—most of them are nocturnal, right? They’re working with the elements. They’re working with the terrain. And I think of grief in that sense. There are oases, there are these rich, beautiful steppes or springs. I think grief brings a depth to life and a connection with the sacred when we face it. A cactus is thorny. It’s not easy. A cactus is rugged. Grief is a portal to really having to ask oneself, What means something to me? And it can often completely reshape what we value.

AL: Your character, though very much like other Broder protagonists, seems somehow more grounded—if not accepting of her present state and consciousness, she seems open to a higher self. At one point, she asks her husband, “How did you do it? How do you stay kind?” Does grief create this possibility in her?

MB: They say that pain is a touchstone of spiritual progress. We don’t seek those deep resources when everything is going swimmingly and we’re in a state of peace. There can be gratitude, but we don’t always have to marshal that reliance on a higher power. We don’t have to surrender. It’s that balance between the surrender and the fight, which is a hard one to navigate. The marshaling of a higher self in a fictional character is always interesting because it’s often informed by that struggle. Our characters are often wiser than we are. One of the themes of the book is that difference between empathy and compassion. She’s able to have more empathy for her father’s thirst and not take it so personally because she experiences her own thirst in the desert. But compassion is very hard—a difficult trait for a human being—when we don’t identify or we can’t even understand the feelings of someone. Not even the experience, but the feelings. To have that sympathy, that takes muscle. So for her, lost in the desert becomes a bit of a foxhole prayer—“G. O. D., gift of desperation.”

AL: Tell us about Best Westerns.

MB: I love the Best Western! I love celebrating something that’s sort of a little bit low brow, a little bit Americana. I love American Kitsch and I love American desert Kitsch. I always stay at the Best Western in Vegas where my sister lives, and I stayed there a lot while my Dad was in the ICU on the East Coast. Since we couldn’t go see him for long stretches due to Covid, I drove back and forth between my house in LA and Vegas to be with her. Like the protagonist, I was trying to escape a feeling.

AL: What calls to you about the desert?

They say that pain is a touchstone of spiritual progress. We don’t seek those deep resources when we’re in a state of peace.

MB: The light, the foliage, the gorgeous, Joshua trees. That things can grow and survive and that there’s beauty even in the really, really rugged terrain. That to me is amazing. The resourcefulness of the animals and plants that live there. And the concealed nature of things. There’s a lot of life going on, even though it may not appear that way on the surface.

AL: Was there anything that surprised you about writing this book?

MB: I didn’t know she was going to get lost in the desert. And then I was out doing a desert recon trip. I took this hike in Death Valley where nobody gets lost, and I got extremely lost. It was only for thirty minutes, but I panicked. I had thought, “Zabriskie Point’s a very touristy area, I’m just gonna take a walk.” It wasn’t even going to be a hike. I didn’t have water with me—like, I had Coke Zero. And I panicked and climbed up this rock face trying to get back and got all cut up. And when I got back to my car and had finished crying, I realized, Oh, she’s gonna get lost in the desert and it’s gonna be for more than 45 minutes.

AL: What did it mean to dedicate this to your father?

MB: Just tonight, someone who has read the book said to me, “What a beautiful gift you’ve given to your father. You’ve immortalized him.” And I wondered, despite the fact that it is fiction, whether my dad would have liked the father character—who is deeply inspired by him. I wondered too how he would feel about having this part of his life immortalized. There’s never an easy answer to that. But I will always be grateful, and I believe that he would like this too, that I have had the opportunity to immortalize his mustache.