Lit Mags

Secrets Live Inside My Son’s Ears

"The Oracle" by Joanna Pearson, recommended by Wynter K Miller for Electric Literature

Introduction by Wynter K Miller

Anyone older than roughly twenty-four—the age I associate with the end of college and its embryonic, adult-lite cocoon—is probably aware that making new friends is a Herculean task. Without the sandboxes of primary school, the classroom corrals of high school, or the undergraduate campus, finding your people can be harder than finding your soulmate. Unlike dating, which at least pretends to have “rules,” friendship initiation lacks a template. If a woman my age is sitting next to me at a coffee shop reading a book that I love, how can I approach her and communicate—without it getting weird—that maybe we should meet for dinner to talk about the book and not have sex? Is it weird to give her my number? Is it possible to find out her dietary restrictions in advance? Is a mutual appreciation for caffeine and literature really enough to justify this stressful internal monologue? Is there an app for this?!

Nell, the narrator of Joanna Pearson’s “The Oracle,” is forty, married, and the mother of a teenage son. She is, therefore, old enough to understand how rare and special it is to find an adult best friend. She knows that marriage and motherhood, however happiness-filled, cannot replace the life-affirming experience of having someone who looks at the world and finds the same things revolting as you do. For Nell, Lola is that person. “Constitutionally drawn to the art of grossing each other out,” their friendship is built on vomit noise-inducing anecdotes and an ability to see life for what it is: a house of horrors. They have, Nell believes, revealed the disgusting truths of themselves to one another and managed to continue laughing. And yet, as Pearson’s perfectly calibrated story unwinds, Nell begins to wonder how much of her friend she’s actually seeing—and whether there might be value in simply closing her eyes.

It is a credit to Pearson’s particular genius that the end of “The Oracle” is both shocking and inevitable. It’s the kind of story that you’ll immediately want to read again, if only to reassure yourself that what you think you’re seeing was actually in plain sight all along. (It was.) At first, it’s a story about asking questions. How much is it okay to want? How deeply are we allowed to love? Who are you, really, on the inside? But by the end, you’ll realize the questions have changed. You’ll understand that sometimes, it’s better not to ask.

– Wynter K Miller

Associate Editor, Recommended Reading

Secrets Live Inside My Son’s Ears

Joanna Pearson

Share article

The Oracle by Joanna Pearson

You name it, Lola’s found it in someone’s ear. A green Skittle, a watch battery, the tarnished back of a gold earring, a bunched-up bit of mint floss, a Lego head. Insects—yes, of course. Roaches of various sizes, a wasp, a small beetle. Hardened ear wax (cerumen, Lola insists, avoiding lazy colloquialism) resembling the face of Donald Trump. A polished pebble that might have been from the bottom of a fishbowl. Lola tells me about her discoveries. I devise ways to one-up her, which is difficult because I work from home, hunched over a laptop, scrolling through accounts receivable. Still: there is black mold in my dishwasher, a rotting ham sandwich discovered in the backseat of the car, ingrown hairs morphed to suppurating boils—the world rampant with revulsions when you only pause to look. I feel a little happy surge when I can make Lola groan with laughter. We are constitutionally drawn to the art of grossing each other out. It’s a trait that bonds us. Prior to meeting Lola—despite my marriage, my son—I felt alone.

“You should have seen it, Nell. It looked like a spider leg at first,” Lola says. She’s an audiologist. Her day is spent playing tones of various frequencies, peering into ear canals, testing cochlear implants, and, apparently, extracting foreign objects.

“It was right by his eardrum. I was afraid to pull it out.”

I make a gagging sound. It used to be stories of her first dates that elicited vomit noises from me: the nose-pickers and start-up bros and CrossFit dudes with eye-stinging cologne, the cycling-enthusiast/curriculum-specialist who took her to the fanciest restaurant within a hundred miles, chose the finest wine on the menu, three starters, and two mains, then left her stranded with the bill. Admittedly, with each story, I was a little relieved. She was still mine. Dating is a shit show, Lola assures me. A house of horrors. So, it turns out, is audiology. And human life in general—aging, this mortal coil. Lola and I have recently reached a decade wherein our targeted ads feature luxury compression undergarments and high-end home mustache removal systems.

“It was an overgrown hair. Thick as a wire, like nothing I’d ever seen. About yea big.”

She holds her index fingers at a distance to indicate the length, somewhere between an uncooked spaghetti noodle and an old-fashioned car antenna.

“You’re joking.”

Lola shakes her head. She never jokes, not about ears. External ears—auricles—are beautiful, so elegantly crafted: fossa, helix, lobule, the whole delicate whirled shape. She speaks of them in a way that’s almost fetishistic. Ears are powerful, Lola claims, and also erotic. There’s a special way one of her ex-boyfriends used to touch her ear, caressing it, moving his tongue against it just so. A light flicking movement—Lola has demonstrated, looking like a snake. It’s intimate, Lola’s flickering tongue. I force myself to turn away, though I’m curious. Lola believes in such things—open discussions of sexual appetite, vision boards and crystals, the power of manifesting your dreams, positive mantras, gurus, sound baths, astrology, the totemic ear, summoning up a husband from the mists of your own longing.

“Am I disgusting?” Lola asks.

“A little.”

“I really am disgusting.”

“But I still love you.”

We laugh our sad laughter. There’s an open bottle of rosé sweating on the table between us. It’s dusk, and the deer are encroaching onto the lawn, peering at us from behind the shadows of the overgrown lot across the street. The evening air smells like gasoline and wisteria, the pile of mulch sitting behind our neighbor’s yard. The deer eye us, making a pretense of shyness. There are too many of them here, and they’re no longer afraid of humans. I find them horrifying, unnatural—if someone revealed they were robot deer sent by Jeff Bezos to monitor our every material desire, I would hardly be surprised.

Lola worries she’ll remain single forever. I worry she won’t. Such fear—more accurate to call it panic—can drive a person to do all sorts of things. There is nothing worse than loneliness. Others might not understand but trust me: they have never truly been lonely. Once when Lola and I were at a local brewery, a man with a close-cropped beard came up and started making conversation with us. I could tell it was a great effort on his part. He seemed like someone who hadn’t spoken to very many people, not in a long while, and in this sense, I felt connected to him but also scornful. When Lola went to the restroom, he shyly passed me a card with his name and number to give to her, then fled. I tucked the card into my purse and said nothing to Lola. There was something off about the man, the way he’d looked at her, so greedy for her approval. He wasn’t worthy. I shredded the card into tiny pieces later and threw it away.

I’ve gleaned, however, that there is still someone—or there was. A first love, star-crossed, the outline of whom I can’t quite make out. Lola has alluded to him, to the dark circumstances that keep them apart, almost as if inviting me to ask, and yet I cannot bear to probe further. Something—an instinct to avoid the tragic—warns me away. I make jokes instead. Lola worries about her future, the long, blank line of it stretching before her like an empty corridor. Come to our house, I want to say. Come join us! I can see it—a kind of lopsided family arrangement in which Lola exists as—what, my sister? Danny’s special aunt? But we live in a society that loathes unconventional family arrangements, despite the new, idealistic children’s books promising otherwise. I know this and keep my mouth shut.

Danny walks out of the house, humming to himself, wearing shorts that are far too small. He has grown lately, this boy of mine, in body if not in mind. He’s fifteen—a halfling, carrying the stink and weight of manhood, his interests for the most part still those of a child. He’s come into a mammalian hairiness that unnerves me. I still remember the fragrant sweetness of his once baby-bald limbs. He’s a different creature now. His peers are interested in girls and mean jokes. I fear he cannot keep up; I fear he is keeping up too well. Danny loves Greek mythology and sleight of hand and Magic the Gathering, and, quite possibly, a girl in his class, tawny with long, selkie-soft limbs and caramel-colored hair, impossibly remote in her hierarchical position, a demigoddess among his classmates. Danny was born with certain minor anomalies—congenital defects, although I avoid the phrase. Danny’s differences are small, almost unnoticeable, I remind myself. And yet the savageries of children are real. Already there is a social order established, fixed and unmoving, a Brahmin class of adolescents reckless with ease and excessive beauty, predestined to the life of plenty.

For one thing, Danny was born without a right auricle. Or, rather, the external ear that formed there was small and misshapen, useless. A rudimentary nubbin of pink cartilage like the bulb of a perennial. There was no auditory canal. More common in boys, the ENT told us. His left ear is perfect, pristine.

I took him to every specialist. Like any good mother, I sought to fix things. This is how I met Lola. At the time, I’d felt half-mad—isolated and milk-stained, sleep-deprived, fit to be locked up in an attic. I believed I’d finally revealed the truth of myself to my husband Peter, who’d met me during a year in my life when my skin had been firm and I’d been doing a successful imitation of my most appealing college roommate, Connie Whitaker, a lovely, laughing girl who seemed to be pulled through this world on a gossamer thread of goodwill. But the jig was up; I’d been reduced to a heap of rubble. Lola had touched my wrist that day in such a way, so gently, that I’d burst into tears. She was, is, Danny’s audiologist, from the time he was a baby. One might hardly notice Danny’s asymmetry now. He can hear well enough with his other ear. Not everything, you learn quite quickly as a mother, is within your power to perfect.

“I have no right auricle,” Danny used to say, a child who always preferred precision in his terminology—only back when he was little and first met Lola, he pronounced it “oracle.” “I have no right oracle.” He said it forlornly. A bright child, an early reader, he was interested in fortune telling and airplanes and ancient Egypt, so I pictured the absent ear as a cave in Delphi. Lola has always appreciated his clinical specificity, declaring him from the start to be a remarkable child.

“Hi, Dan,” Lola says, and Danny stops humming. His eyes dart to us, and he gives a little wave. I watch something flicker from his face to Lola’s—a silent exchange that I cannot decipher. She looks down. Danny has already resumed his humming and walked away. They’re close, my son and my best friend. Lola has been like a godmother of sorts since Danny was small, taking him for little outings, tagging along with me for his school events. As he’s gotten older, she’s begun hiring him for little projects around her house—basic landscaping, moving furniture, and the like. I know it’s an excuse for them to spend time together, to make Danny feel helpful, and her efforts—his pleasure in those efforts—pleases me.

“Don’t worry,” I say, feigning obliviousness. “He ignores me, too.”

Lola sighs, as if I require great patience.

“He’s perceptive. He senses things the rest of us miss.”

Lola has always claimed that Danny is wise beyond his years, attuned to reverberations beyond our humdrum day-to-day. It’s a pleasant fantasy. Her belief in my boy moves me, even if I do not share it.

“I don’t know.”

“He’s gifted,” Lola says, and I love her for it.

“The other kids leave him out.”

There are girls in Danny’s grade with the grace and bearing of young duchesses, boys with the stubble of full-grown men. Last week, I heard at carpool that Kevin Riley and Kayla Hutchins were spotted buying Plan B at the Walgreens on Cedar. Peter, attempting to be a progressive-minded parent, one embracing openness, gave a package of condoms to Danny last fall—untouched, I’ve noted. There’s a degree of developmental mischief in adolescence that strikes me as necessary; I am bracing myself for it.

When Danny was eight, there was a trick he learned involving a silver dollar that he did over and over again, for weeks at a time. He’d wave his hands, beaming before us as he made the coin disappear. Then, delighted with himself, he’d reach behind one of our ears and retrieve it, laughing. It was a good trick. He had polish, panache, especially for an eight-year-old. We laughed with him, even while we grew weary of watching.

When Danny stopped performing the trick abruptly, I asked what happened. He lost his special coin, he said. The 1921 Peace silver dollar with a splotch of purple enamel paint that he’d gotten from Grandpa. You could do it with another coin, I suggested. Any coin, really. But he shook his head. No other coin would do. Danny, a child who has always known the power imbued in particular objects.

That same week I saw a group of children standing outside the school awaiting pickup. A group of boys and girls. In one of their hands something silver flashed. The boy made an exaggerated pantomime of a magician before a crowd, stretchy, clownish grin and mincing steps. There was the flash of silver pulled from behind someone’s head. The boy, big and handsome for his age, bowed. The whole thing was overdone. A mockery.

Danny stood at a distance by himself, dragging the toe of one shoe through the dirt in indecipherable patterns. When he got in the car I asked if he knew what had happened to his silver dollar from Grandpa.

I lost it, he said at first. Then, No, I gave it away.

I knew then that one of the other children had taken Danny’s silver dollar from him—my child, my boy. A fury rose within me, wild and winged and taloned, but I said nothing. The list of what must be left unsaid as a parent is endless.

The list of what must be left unsaid as a parent is endless.

“I need your help clearing out the old shed, Dan,” Lola calls. “I’ll pay you.”

Danny lifts his chin slightly in acknowledgment and then returns to what he’s doing: a hole, I see now. A hole in the corner of our yard. There’s no telling this time, I think. Peter says we have to let him follow his interests, even if it means burying chicken bones, waving feathers, making bicentennial silver dollars disappear, creating time capsules, conducting the odd rituals of a juvenile soothsayer. Peter has found porn in Danny’s room, but he promises me it is of an ordinary variety—unconcerning, normal even, Peter tells me. Not the ornately constructed cruelties some men watch, slick and pulsing parodies of ownership. Even so. I still find Danny sleeping with his thumb tucked into his mouth, so I cannot square it.

“How is he?” Lola asks, and she makes a hand motion that suggests she means Danny’s hearing. Danny is prone to cerumen impaction in his working ear, requiring periodic washouts.

“Hard to say given how he ignores me.” The curse of motherhood, I think, is the inevitable derision you accrue, the eventual disregard.

Lola waves a hand, as if brushing my words away. She lifts the bottle of wine gently, topping off my glass. From where we sit, we can see the right side of Danny’s head, the deaf side. There is an ear there now, one crafted painstakingly by a surgeon. A work of art, my husband Peter says. Impressive, agrees Lola. She declares it an excellent imitation, good enough to fool anyone but a connoisseur like herself. I can discern its falseness, though, and the fact of it sometimes bothers me.

“Peculiar children grow up into interesting people,” she says.

I don’t answer.

Lola sips her wine. She studies Danny, the hole he’s dug. The family of deer is rustling in the dimness beyond us, the rabbits growing bolder. If I listen hard enough, I imagine I can discern the sound of growing things, shoots unfurling, the restless soil being churned. We do not know it yet, but things are about to change.

“I want a baby.” She pauses, takes another sip. “I still haven’t given up. It happens all the time to women our age.”

Lola and I have both turned forty. Lola wants a child badly. Her yearning is hard to witness. We do not meet each other’s gaze, the two of us watching Danny work at his hole. He is singing to himself, and the song carries—a song for much younger children, an absurdist song of repetition and escalation, an old lady swallowing a fly and then everything else. Perhaps she is hungry with want too, the poor old lady in the song. I cannot bear its melancholy, hearing the song now sung by my son, who is surely too old for it, the relentless and ridiculous refrain. Danny digs away, arranging something I cannot see in the gloaming. His singing is un-self-conscious, the kind of blithe lack of self-awareness that makes me worry for him, for what the other children might say. What they might do. How it will harden him. Sometimes I think Lola might be the lucky one, but I cannot say this to her—not now, not ever.

“You think I’m crazy?”

I think of Lola’s apartment, the disarray of scattered magazines and shucked t-shirts, socks draped over chairs and half-empty snack containers on the counters, the crystals and patchouli, the tattered yoga mat into which her dog has eaten a large hole—the haphazard overflow of a perpetual adolescent. I cannot quite imagine her cleaning up, boiling bottles, carting around a pink-cheeked infant, but none of this is for me to say.

“I think you’re normal,” I tell her.

“Yeah,” she says. “Something crazier will probably happen at work tomorrow.”

Afterwards, her words feel like foreshadowing. Lola found the first jewel the very next day.

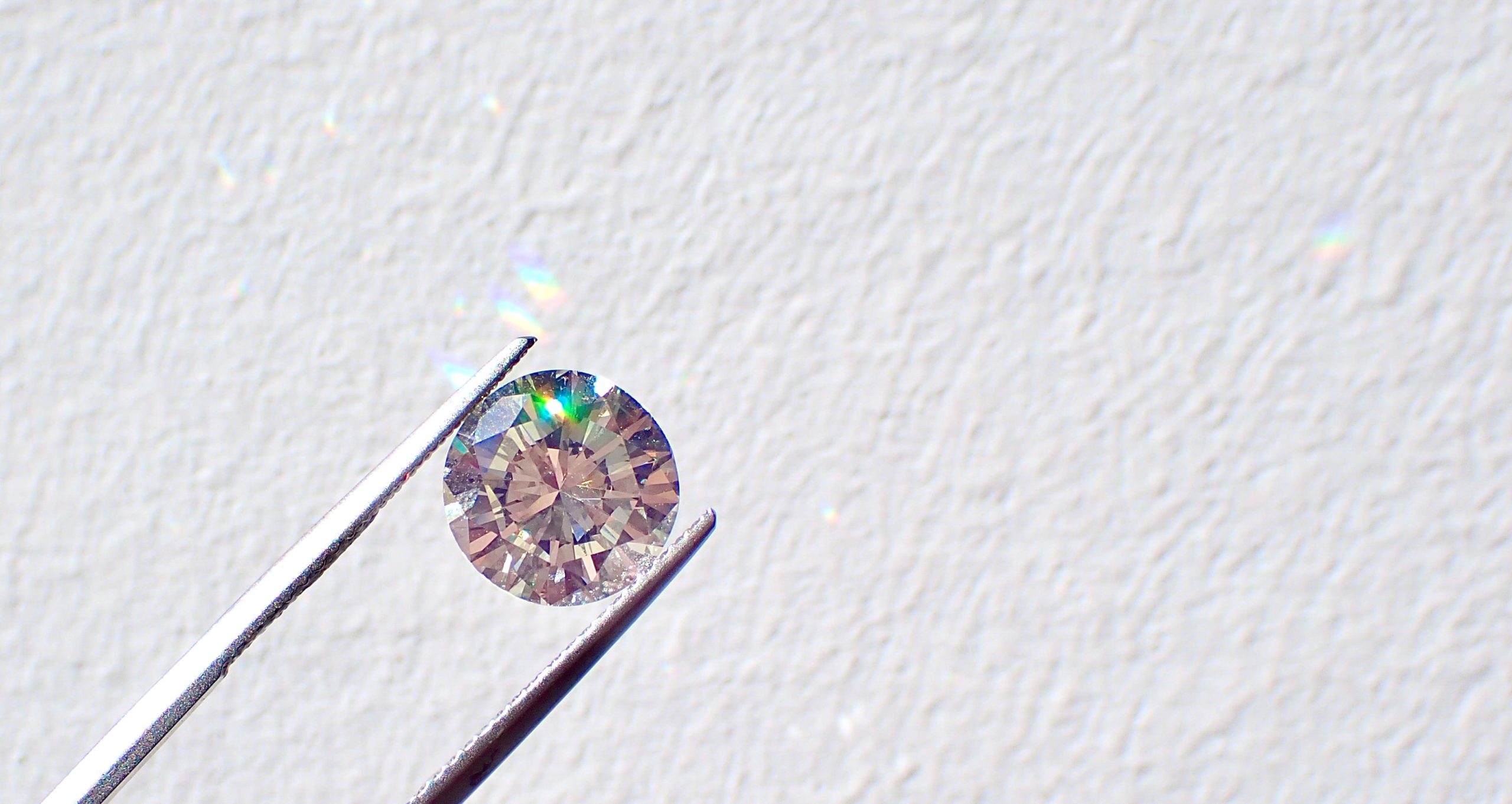

It’s a diamond. Pear-shaped, three carats, flawless as far as Lola can tell. Extracted from the ear canal of an 88-year-old man complaining of unilateral hearing loss.

“How’d it even fit?” I ask her.

She’s giddy, breathless on the phone. Normally we text. Phone calls are for truly notable events. Emergencies.

“He had big ear canals.”

She laughs into the phone. The old man, her patient, she tells me, was a widower. His wife loved jewelry, but he doesn’t think he recognizes this diamond. But it must be hers. Maybe, he speculated, it fell out of its setting, then worked its way over to his pillow, and he slept on it such that it worked his way into his ear.

“Seems improbable.”

She laughs again. It doesn’t matter, her laugh seems to say, because the world holds possibility now. If diamonds the size of acorns can fall out of people’s ears, what else might the future hold?

“It’s the only thing we can come up with,” she says. “He certainly didn’t shove a diamond up there. My patient wanted to give me a reward,” she continues. “He wanted me to keep the diamond at first, but I wouldn’t accept it.”

“Wow,” I say. “It can’t be real. It must be some kind of prank.”

She doesn’t respond, but I can feel it over the phone—sudden, like a storm cloud. Her mood has shifted. An automaton speaks in Lola’s place, with her voice, her intonation, but no feeling.

In the living room, I can hear Danny and Peter’s soft groans and triumphant whoops as they play a video game together. It’s a pastime I hate, but Peter says it’s a source of connection, a way of accessing Danny. What he sees in our boy then—eyes glazed and glistening in the reflected light from the television monitor, the controller slick in his plump hand—I do not know. It’s in those moments, over the blip and bleep and laser zap, the enemy combatants on screen, that my son is most inaccessible to me.

“He can hear better now. Without that diamond in his ear.”

“I’ll bet. It’s a miracle.”

The first time was saw Danny on the ultrasound screen, that ghost-image of him, the whoosh of his hummingbird heart, I said the same thing. It’s a miracle. Miracles, I believe, are fraught. Turn them on their sides and they can look like curses.

Danny’s shriek pierces the silence. He cannot bear it when the space alien hordes or robot intruders—or even Peter, especially Peter—defeat him. He cries out again. Something heavy strikes the floor.

“Like attracts like,” Lola says. One of her sayings. Were we living in a different time, she would be arranging burnt offerings to the gods, gifts of sheep and goats. She’d believe in augury, favorable phases of the moon; in fact, she believes in these things now, in their modern form, delivered via internet astrologers.

We hang up, and Peter comes into the kitchen to pour himself a glass of water. I can hear Danny muttering angrily in the other room. The world has splintered unforgivably into disappointment, lacerating him. It takes so little, I think, to wound this child, my son. Peter glances at me the way he often does—as if I’m a benign shadow, a pleasant person who is hardly there.

“He says he’s not going to the end-of-school dance,” Peter says. “The girl he wants to go with can’t go with him.” There’s the dull thud of something being thrown in the other room, striking the wall and landing on the floor. Peter looks at me meaningfully, as if the dance explains Danny’s current tantrum. In his mind, there’s always a reason behind the reason. Perhaps he’s right. But Danny also simply hates to lose.

“So he can go solo,” I say. I detest the thought of these dances—an infliction of misery. The administrators should know better. I recall my own luckless youth, my terror as I cowered beside those other girls, my peers, who moved with confidence, abashed and proud of their little teacup breasts, girls who kissed their boyfriends by the darkened bleachers. I was sick with fear, alone, and horrified at my aloneness—hideous, it seemed to me at the time, although in retrospect I see I was only shy and utterly ordinary.

“The other kids are all taking dates,” Peter says.

I consider this a moment—my son, who still sleeps with a plush turquoise seal. My son, filled with such a thwarted ache.

“What about Kara?” I ask.

Kara Evans is our neighbor’s child, a sweet, awkward girl one grade below Danny, his friend since preschool. At least, they used to be friends.

Peter shakes his head. “I don’t think so.”

In the living room, I find Danny curled on the couch. His frustration has dissipated, leaving him hollowed, silent. There are dark crescents beneath his eyes like those I’d expect to see on an overworked adult. Like Lola, he seems to have a way of retreating into himself, turning stony and inaccessible, present in body only. Two hardcover books lie on the floor, where Danny has thrown them.

“Hey buddy,” I say, taking the spot next to him on the couch. He shifts his body away from me, almost imperceptibly. He manages a reptilian stillness, his hooded eyes at half-mast, breath barely perceptible. What I wouldn’t give to know what he’s thinking.

“Dad says you aren’t going to the dance?”

His silence hardens. Is it even possible for him to absent himself further from me? I can smell the faint, unwashed musk of his hair, the hint of recently consumed cheese crackers on his breath. As a baby, he was the most impossibly beautiful creature, and although I love him, the ugliness I see in him now surprises me—a measure of his maturation into a wholly separate self.

“You could take Kara, I bet. I could ask her mom.”

He turns to me, and his mouth parts as if he’s about to say something. His lips shift to form not a smile, but a scornful expression. A sneer.

“We used to take friends as dates,” I offer. “No big deal.”

He rises from the couch, shaking his head at me. Like I’m an imbecile, a fool.

“You have no clue,” my son says, and I swear, his voice is an octave lower than the day before.

I check Danny’s laptop sometimes—or, rather, I used to. I did it frequently, hoping I might learn something about him, information he might want me to know on some level, but would never be comfortable sharing. I combed through it all: his browser history, webpages he’d visited, news articles he’d clicked, whatever profiles he’d last viewed on Facebook. Peter installed a parental control app that prevents explicit sites from showing up, but there’s still plenty there to paint a solid picture of Danny’s insecurities. His search history includes: How to tell if she really likes you . . . , easy ways to build muscle mass . . . , is it normal if . . . . “How to Drive Her Wild in Bed” was the headline of one article he’d clicked on several times, and seeing this, I wanted to shrivel up and die—although I wasn’t sure if my embarrassment was for Danny or myself. Normal mischief, I reminded myself. Normal curiosity.

There are, of course, the expected sites: video game reviews, Harry Potter fan fiction, critical essays on The Sun Also Rises, skateboarding videos. This viewing history reassures me. My boy has a boy’s interests.

Each time I snoop, though, I’m overcome with shame at myself, preemptive humiliation on my son’s behalf at what I might find. I dread stumbling on evidence of some darker current—incel chatboards, QAnon threads, all those angry young men yelling into the void. And yet I can’t stop looking. Lately, he’s been reading up on love spells and state marriage law. These facts confound and break my heart.

The other day when I looked, though, his top search phrases were how to get your mom to stop spying on you and what to do if your mom is the gestapo. The rest of the history had already been cleared. Fair play to you, Danny, I thought to myself. Message received. I closed the laptop, putting it back carefully just as it was, and closed the door softly as I slipped out.

Two days later, Lola finds a small ruby in the ear of an eighteen-year-old volleyball player. The next week, she plucks a sapphire from a retired math teacher. That Friday, there’s another ruby inside the ear of a 43-year-old military veteran. It’s wedged in so tightly that the man’s ear bleeds. By the following Tuesday, she’s pulled a freshwater pearl from a seventy-three-year-old former actuary’s left ear, and the local news station wants to interview her. There’s another pearl in the ear of a local orthodontist that afternoon. By Wednesday, the story’s picked up by the Associated Press.

Something strange is happening, an unspooling sequence of events from a fairytale. Danny and I meet Lola for lunch at the deli downtown. We sit at the picnic tables outside with our thick-cut sandwiches and wax cups of lemonade. Lola’s eyes seem too bright, her pupils enormous black holes. She hugs Danny, talking more quickly than usual, like she’s about to laugh or cry, like she’s just inhaled a bunch of nitrous oxide.

Lola’s going to be on Good Morning, America, she tells us. People are saying she has a kind of Midas touch, that she’s been blessed, or that she’s a witch. Or perhaps a charlatan, an illusionist pulling off a riveting prank that will eventually be revealed as the viral marketing campaign for a forthcoming movie. Some people are claiming the stones she’s discovered are fakes, junk-shop glass.

“But they’re real!” she insists to Danny and me, tearing into a bite of her sandwich. A local gemologist has volunteered to verify this fact. “People are so close-minded.”

None of Lola’s recent discoveries compare to the original diamond she found. The newer gems are smaller, mere accent stones rather than centerpieces.

“It must be a copycat thing,” I say. “Ever since that first diamond. It somehow got wedged in that guy’s ear by accident, like a one-in-a-million fluke. And ever since then people have heard about it, and, you know.” I make a gesture as if inserting something tiny and invisible into my ear.

“Stick rocks up their ears then come to see me?” Lola asks.

“Exactly.”

“But why?”

“To perpetuate a story. To be part of it. For attention. The same reason people participate in TikTok challenges.”

“The ear diamond went viral?”

“Exactly.”

“That’d be so weird, though. For people to do that.”

“It’d be absurd. But people are absurd.”

Danny slaps his sandwich back down on his plate so abruptly the plate jumps. Across the way, I see Kara Evans and her mother walking into the deli. Danny seems to glance at them with veiled, feline interest. His lip curls.

“You don’t believe in shit,” he mutters.

I hear him, but I don’t fully believe I’ve heard him.

“What?”

“I said, you don’t believe in shit.”

Danny stares at me hard. He’s delivered each word as a punch this time, puncturing the helium giddiness in Lola’s voice. Her brow crinkles, then softens to a look of concern.

I look at him. I do believe in certain things. I believe there are things we want—that we need—to keep telling ourselves; in the wish to be part of something larger, to experience something exhilarating. Magical. To not feel alone. But somehow, I cannot explain this to Danny.

Danny rises from the picnic bench. He grasps Lola’s hand suddenly, with such urgency I hardly know him.

I believe there are things we want—that we need—to keep telling ourselves.

He stands there a moment, his mouth moving as if he’s going to speak but says nothing. I remember the fairytale about a princess out of whose mouth no words fell, only jewels. Or was it frogs? Lola studies him, and it seems some knowledge is transmitted, something beyond my comprehension. He drops her hand and walks away, leaving his sandwich unfinished.

“Well,” I say after a moment. My gaze follows Danny across the patio, the stoop of his shoulder, the coiled way he carries himself.

When I turn back to Lola, I see that she is slumped in her chair, eyes half-closed. She blows a strand of hair off her forehead. All the pulsing manic energy seems to have dissipated.

“Everything okay?”

Her eyes widen, and she looks startled, almost like she’s forgotten I’m still there.

“Oh, Nell,” she says. “No, it’s all good. I’m manifesting. It’s all coming to fruition.”

She smiles so hard her eyes crinkle into two lines. She looks like she might laugh or cry.

“Oh, Lola.”

I reach for her, awkwardly across the picnic table. Then, thinking better of it, I rise and move beside her, pulling her close to me, my nose in her hair. She smells sweet, like freesia and the bacon from her sandwich. Across the way, Danny has disappeared. Nothing but the moodiness of a teenager, I tell myself.

“I just needed to believe. To commit to my vision. It’s never the way you think, when your prayers are answered.”

She’s smiling and crying, looking at me with such raw joy that I’m terrified to ask her what she means.

“I thank Danny. He’s been crucial, Nell. He’s been my guide in so many ways.”

I check Danny’s room sometimes, too—his drawers and closets, under his bed. Or, rather, I put his laundry away, and when I do, I can’t help but notice things. Inconsequential things, mostly: an empty can of lime La Croix, a half-finished bag of Doritos (despite the fact that I beseech him not to snack in his room), a crumpled trigonometry quiz, notes for a paper on Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, a ticket stub from the local movie theater, scraps of yellow paper with inscrutable messages to himself, words in tiny print, numerals like 1111, 222, 3333 written over and over.

Yesterday, when I was tucking Danny’s folded t-shirts back into his drawer, my hand brushed against something silky. I let my fingers linger and felt the edges trimmed in lace. Hesitantly, I pulled the fabric out and saw a pair of women’s panties. Hanky Panky—the expensive type I know Lola is partial to. They were lavender, buttery soft in my hands. Call it an instinct, a gut feeling: I knew they were hers.

I imagined how it happened: Danny, finding himself with a moment alone over at Lola’s, slipping into her room, pulse quickening as he peered into the drawer of fancy undergarments in sherbet colors rolled tightly into rows, neat as a department store. Danny, allowing the tips of his fingers to brush gently over the fabric. It would be so easy to slip a single pair into his pocket. A reminder. A talisman.

I will tell her, I told myself. About this violation. Completely inappropriate. Danny would have to be confronted. But he was also just a child, a child surging with hormones, yes, but a child nonetheless. It would ruin everything with Lola—perhaps make things so awkward she’d no longer be comfortable coming to our home. And Danny would be humiliated in front of the one person who saw such specialness in him. And what if I was wrong? If the panties were from elsewhere? A school friend, a buddy, some sort of ill-conceived department store shoplifting dare. I would wait and make sure, I told myself. Either way, the fact of it would need to be confronted. I could take my time and make sure I handled it properly.

A single pair of panties would hardly be missed.

Peter is home when I get back, working in the garden. He swipes the back of his hand against his forehead and waves at me. He looks natural out there, handsome—the sort of person who has always existed honestly with himself, to whom things have come naturally. Even the plants seem to curl toward him, flowers unfurling in his presence, as if he is the sun.

“Good lunch?” he asks.

“Have you seen Danny?”

“He’s upset.”

Peter gestures to the little patch of undeveloped land behind our house. The woods, Danny calls this area. The forest. The river. It’s a scraggly patch of land covered in weedy overgrowth, kudzu and muscadine, wisteria and honeysuckle, burs and briars and beggar’s lice. A drainage ditch runs through it. There are copperheads out there. Ticks and mosquitoes. Danny loves it, despite our protests. He’s set up various little encampments beneath the trees since he was little. Neither Peter nor I have the heart to tell him how far this is from a real forest, how pitiful it is by comparison. He’s laid claim to it. It’s his.

“Oh.”

“I think he needs a moment to himself.”

Peter squints again, as if trying to discern a figure just beyond me. The sun is intense, a white-hot beam of heat irradiating my shoulders and back. A wave of nausea passes like a darkening cloud.

“Oh.” I say it again, stupidly, an empty syllable.

“Nell,” Peter says. “Wait. We’ll talk to him this evening.”

“I’m finding him now.”

I’m gone before Peter can answer, through the backyard and down the hill, to the sloping bank. There’s a chain-link fence with a slumped section from people having climbed over and through it so many times. I pull myself over, already starting to sweat.

The trickling drainage ditch almost looks like a stream, but it has the queasy smell of sewage. A fat groundhog startles and moves from my path. I cross the water and haul myself up the other side. There, beneath a large overhanging stone is a flat area, a kind of half cavern. Crouched beneath it, I see Danny, in his bright blue shirt, kneeling on the ground. I’m approaching from his deaf side, so he can’t localize me at first.

“Danny!”

He spots me, scrambling backward, crab-like, trying to conceal whatever’s on the ground behind him. I can see a rough spread of color, objects. Items of clothing. A pair of shoes.

“Leave me alone!”

“Danny.” I’m breathing heavily, climbing the rise. “I just wanted to check on you.”

“Go away!”

He’s flushed, splaying his arms, trying to conceal the ground beneath him. I can see it’s the large dirt drawing of a person, windblown and smudged now—but I can discern legs, arms, a face. There are a pair of shoes where the feet would be, shorts, a shirt, pine straw arranged for hair, crude features carved into the mud that would be the face, runny and distorted by recent rain. A woman, I realize, noting the way the dirt is humped into two discrete mounds for breasts. A mud woman who is, I see now, adorned in belongings I recognize as Lola’s: a running tank top, a hemp bracelet, soft pink panties trimmed in lace. A black bra. There are two small gold hoops I recognize in the spots where the mud woman’s ear lobes would be.

“That’s Lola’s stuff,” I whisper.

A silence follows, suspended between us, iridescent, like a bubble, and then something falls in Danny’s face. He scowls.

“It’s nothing,” he says, answering the question I haven’t asked. “I don’t even need it anymore.” The mud-woman, Lola, lies supine beneath where he sits—a grotesquerie.

“You stole from her,” I repeat, my throat filling with a sour taste. “And this—get rid of it, please.” I gesture to the mud-woman, although I can’t look at her again.

“I didn’t steal from Lola,” he says. His face is defiant now, dark eyes flashing as he rises to stand. He is taller than I am now, this son of mine. It’s hard in this moment to remember that he’s the same child I bore. He could be anyone—a stranger, carrying hatred in the lines of his jaw.

“You did.” I point. The answer is obvious. It’s all there—not just a single pair of undergarments, but a whole treasure trove. A sick shrine. The urge to vomit rises within me.

“These were gifts,” he says.

“Gifts?”

There must be incredulity, confusion on my face, because he scoffs at me, a horrid sound. Hard-edged, like glass.

Then, a look—satisfaction? smugness?—passes over him.

“You’d never understand. You’re jealous.”

I’m parched. I cannot speak.

“You never listen,” he whispers. “You poke and prod, but you never really listen.”

“Get rid of that,” I say, pointing to the horrible drawing.

“And you’re socially awkward—I got that from you. It’s your fault.”

“Get rid of it.”

“I don’t need it now anyway. Not anymore.”

We stand facing one another, wordless. I watch his skinny shoulders rise and fall with his breath. Then I’m tearing back down the slope, letting the sharp grasses slash my ankles and calves, stepping right into the dank, reddish water. Branches slap against my face and arms and tears sting my eyes.

Back at the house, I stop on the patio, gasping for air, a diver surfacing from a dark pool.

Peter is putting away dishes when I go inside. He turns to me.

“How’s Danny?” he asks.

“Fine,” I lie, although there is a flip-flopping in my chest.

He smiles despite the sadness in the corners of his eyes. Peter is an attractive man, good with people, easily liked, quick to make friends with new neighbors and passersby. In this regard, maybe he will never understand me, or Danny—at least not completely.

Here is what happens:

Danny skips the school dance, and Peter and I muster a ferocious good cheer. We insist on watching one of Danny’s old favorite movies as a family, eating takeout pizza and drinking flavored seltzer. There are explosions onscreen, large-bosomed women in sleek outfits, macho bonhomie between the main character and his sidekick. Goofy jokes, an obvious villain, a bank heist. Peter guffaws appreciatively. Danny sits sullenly apart from us in the corner of the room while elsewhere, in a dim gymnasium strewn with multi-colored streamers, all the other sophomores dance with one another, rocking on their heels together to the slow songs beneath strobing lights.

The next day, Lola, appears on Good Morning, America, talking about her discoveries, the gemstones she’s found in the ears of everyday people, like it’s a feat of her own ineluctable willpower. What faith—to believe you’ll find a glowing diamond where none should be and, lo, to pluck it free!

Danny and I watch Lola together on television. Her face appears pale and painted, her smile strained. The skin is stretched too thin. She’s a grinning skull on the LED screen; I think of the jeweled catacombs of kings, piles of treasure with empty-eyed skeleton guards, memento mori. Lola moves her hands quickly, drawing elaborate shapes in the air, making expressions of surprise. She’s describing love vibrations and manifesting, the laws of attracting such good fortune, demonstrating how she worked the first diamond out of the old man’s ear ever so gently. The hosts gush. Speaking of the power of manifestation, they announce, they have a big surprise for Lola.

Before the live audience, out walks an older gentleman in a rumpled suit, looking bashful and handsome, waving to the crowd. Lola gasps with apparent happiness. Her hands are at her mouth. The man smiles and bows, and a rolling script at the bottom of the screen declares him to be Lola’s patient, the one from whose ear she extracted the first diamond. Good Morning, America has arranged all of this. He holds one hand outstretched, offering Lola a small velvet box, inside of which rests a diamond—the very diamond! It is familiar to me, but maybe every diamond looks the same. The old man, a widower and believer in true love, knows—he just knows!—there’s a special someone in Lola’s life. And he wants the diamond to be hers, with all his blessings and well wishes. Unconventional, perhaps, but he wants Lola to have the opportunity to use the diamond to propose!

I watch Lola hug the old man. Yes, there is a special someone, she says. Her soulmate. The hosts gush and ask Lola to tell them more. She describes a man with salt-and-pepper hair, a financial planner with a generous laugh and a penchant for pickleball and Stracciatella gelato. A figment, I realize. A fiction. I watch her perform this dumb show for an audience of millions as slowly, a cool knowledge settles around my throat. Lola’s eyes seem to bore directly into mine from the television, and I realize I know who she really means. I’ve noticed what she’s wearing around her neck—a silver dollar with a splotch of purple enamel hanging on a silver chain. It dangles there, suspended just above her breasts. A lucky charm. Danny’s lost coin. A coldness, a runnel of water on a wall of ice, rolls down my back. I think of every child, Danny included, moving along a conveyor belt into full personhood, into inscrutability.

“There,” I whisper to Danny. “Your coin.”

But Danny has already left the room. He knows. And maybe I know nothing: maybe I have always known. The blood rushes through my head so fast, in such mighty torrents, that it’s deafening.

Peter walks in. He is holding something, his face knotted with concern: an empty bracelet, an anniversary gift that he gave me on the tenth year of our marriage, only now the rubies and sapphires with which it was inlaid are gone. The prongs are splayed, having been pried apart. And where are the pearl earrings I inherited from my great aunt, Peter wants to know? Or better yet, the engagement ring I find too cumbersome to wear, its gem a family heirloom passed down from Peter’s grandmother? Have I checked my jewelry box recently? He’s worried, Peter says, that Danny’s taking things.

I furrow my brow but say nothing. A new solution is rising in my mind—elegant and wrong, but also right. Soon enough, Danny will turn eighteen. I can stay quiet until then. Like an illusionist at a child’s party, I will perform my own magic, will pluck, not jewels or coins, but tiny, folded bits of fortune-cookie paper from their ears—Danny’s, Lola’s, Peter’s. Voilà! They will laugh and applaud, all of us together, right there, in the kitchen. Your true love was right here all along, I’ll read aloud—three identical fortunes, three fates sealed. It will be good, I promise myself. It will. As if I hold authority within me. A prophecy. As if saying it will make it all true.