Lit Mags

Hole

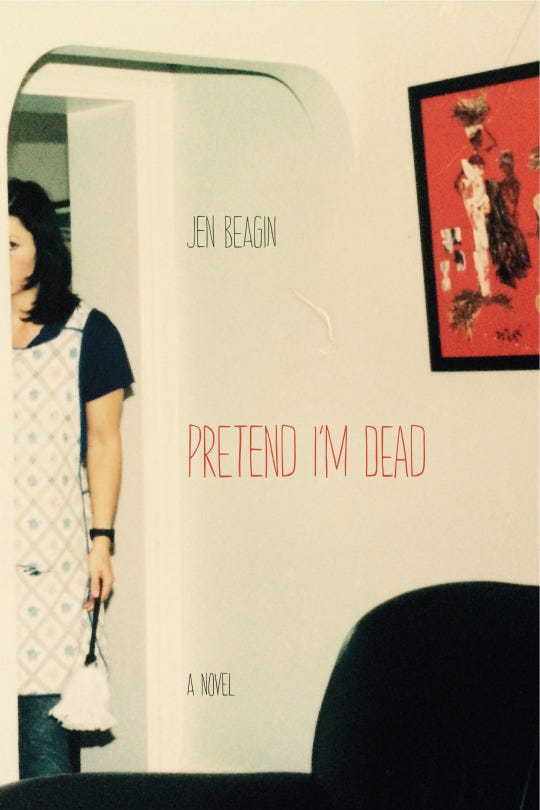

Excerpted from PRETEND I’M DEAD by Jen Beagin, Recommended by Emily Books

AN INTRODUCTION BY EMILY GOULD

As Jen Beagin’s story begins, we meet a narrator who dresses up for her shift at a needle exchange because she’s eager to see a junkie she has a crush on, a man she’s mentally nicknamed “Mr. Disgusting.” By the second page, they’ve finally struck up a conversation. Mona is alive to the minutiae of Mr. Disgusting’s physical presence, which is, as you’d expect, disgusting — but, we immediately understand, also endearing. “He was wearing the leather jacket she liked — once white, now scuffed and weatherworn, with a cryptic tire mark running up the back. There was a dead leaf in his hair she didn’t have the nerve to pluck out.”

I fell in love with Jen’s writing in much the same way Mona falls for Mr. Disgusting. I was wary. Even though this book came to me from a trusted friend, the great writer Elisa Albert, I wasn’t expecting to like it. It had been a long time since I’d read a novel. I was a new parent, exhausted and low on patience, and the only books I’d read for weeks had Baby or Sleep in the title, usually both.

But as I read these first few pages I found myself noticing details that hooked me, and then all of a sudden I was in deep, unable to stop reading. I had to find out what happened to Mr. Disgusting (spoiler: nothing good!) and, more importantly, to Mona. What else would a woman whose romantic type is “obviously doomed” go on to do in these pages? The answer is totally unexpected.

This book is the magical kind that illuminate a small, self-contained interior world so completely that you feel that you’ve experienced another life within your own. As I closed Pretend I’m Dead, I felt unaccountably sad — not because of what happens in the story, which is a little bit sad, but because I wanted to keep spending time with Mona, and stay inside her head. The excerpt here is only the beginning of the story, and this book is the beginning of a literary career I’ll be watching closely, hoping to fall in love again with something or someone disgusting, compelling, funny and real, like all of us truly are.

Emily Gould

Co-Founder, Emily Books

Hole

Jen Beagin

Share article

by Jen Beagin

Excerpted from PRETEND I’M DEAD

He lived downtown, in a residential hotel called the Hawthorne, a six-story brick building sandwiched between a dry-cleaning plant and a Cambodian restaurant. When she arrived three Cambodian gang members were loitering in front of the restaurant. It was broad daylight and she felt overdressed in her black kimono shirt and slacks. She also felt whiter and richer than she was. The sixty bucks in her pocket felt like six hundred.

The lobby had the charm of a check-cashing kiosk. A security guard stood at the door and a pasty fat man sat in a booth behind thick, wavy bullet-proof glass. Mona slipped her ID through the slot.

“Who you here to see?”

She gave him Mr. Disgusting’s name.

“Really?” he asked, looking her up and down.

“Yeah, really,” she answered.

Mr. Disgusting came down a few minutes later, wearing gray postal-worker pants and a green t-shirt that said “Lowell Sucks.”

“You look nice,” she said.

“I scraped my face for you.” He took her hand and brought it to his bare cheek and then clumsily kissed the tip of her thumb. She blushed, glanced at the fat man behind the desk, who studied them with open disgust. “You get your ID back when you leave the building,” he said into his microphone.

They shared the elevator with a couple of crackheads she recognized from the neighborhood. Mr. Disgusting kept beaming at her as if he’d just won the lottery. For the first time in years, she felt beautiful, like a real prize. They got off on the third floor.

“It’s quiet right now, but this place is a total nuthouse,” he said.

“Doesn’t seem so bad,” she lied.

“Wait until dark,” he said, pulling out his keys.

His room smelled like coffee, cough drops, and Old Spice. All she saw was dirt at first, one of the main hazards of her occupation. She spotted grime on the windowsill and blinds, dust on the television screen, a streaked mirror over a yellowed porcelain sink. The fake Oriental rug needed vacuuming, along with the green corduroy easy chair he directed her to sit in.

Once seated, she switched off her dirt radar and took in the rest of the room. She’d expected something bare and cell-like, but the room was large, warm, and carefully decorated. He had good taste in lamps. Real paintings rather than prints hung on the walls; an Indian textile covered the double bed. He owned a cappuccino machine, an antique typewriter, a sturdy wooden desk, and a couple of bookcases filled with mostly existential and Russian novels, some textbooks, and what looked like an extensive collection of foreign dictionaries.

“Are you a linguist or something?” she asked.

“No, I just like dictionaries.” He sat directly across from her, on the edge of the bed, and crossed his legs. “I find them comforting, I guess. Most of these I found on the street.”

“You mean in the trash?”

He shrugged. “I’m a slut for garbage.”

“Your vocabulary must be pretty impressive,” she said. “Do you have a favorite word?”

He thought about it for a second. “I’ve always liked the word ‘cleave’ because it has two opposite meanings: to split or divide and to adhere or cling. Those two tendencies have been operating in me simultaneously for as long as I can remember. In fact, I can feel a battle raging right now.” He clutched his stomach theatrically.

She smiled. It was rare for her to find someone attractive physically and also to like what came out of their mouths.

“What’s your least favorite word?” he asked.

“Mucous,” she said.

He nodded and scratched his chin.

“I wasn’t born like this,” he said suddenly. “Moving into this hellhole did quite a number on me — you know, spiritually or whatever. I haven’t felt like myself in a long time.”

He’d lived there seven years. Before that, he owned a house in Lower Belvidere, near that guns and ammo joint. He’d had it all: a garage, a couple of cats, houseplants. She asked what happened.

“I was living in New York, trying to make it as an artist,” he said. “I had a couple shows, sold a few paintings, was on my way up. During the day I worked as a roofer in Queens.” He stopped, ran his fingers through his hair. “One night I was on my way home from a bar and I was shit-faced, literally stumbling down the sidewalk, and out of nowhere, two entire stories of scaffolding collapsed on top of me, pinning me to the concrete. A delivery guy found me three hours later. Broke my clavicle, left arm, four ribs, both my legs. Bruised my spleen. My fucking teeth were toast.

“After I got out of the hospital, I couldn’t exactly lump shingles as a roofer, so I crawled back to Lowell. Then I got this big settlement and was able to buy a run-down house, but one thing led to the other.” He pointed to his arm. “I pissed it away, made some bad decisions. I’ve been living in a state of slow panic ever since.”

“Sounds like you’re lucky to be alive.”

He shrugged. “Am I?”

She felt her scalp tingle. For as long as she could remember she’d had a death wish, which she pictured as a rope permanently tied around her ankle. The rope was often slack and inanimate, trailing along behind her or sitting in a loose pile at her feet, but occasionally it came alive with its own single-minded purpose, coiling itself tightly around her torso or neck, or tethering her to something dangerous, like a bridge or a moving vehicle.

Mr. Disgusting plucked a German pocket dictionary off the shelf and leafed through it. He was certainly a far cry from the last guy she dated, some edgeless dude from the next town over whose bookshelves had been lined with Cliffs Notes and whose heaviest cross to bear had been teenage acne.

“Do you know any German words, Mona?” he asked, startling her. It was only the second time he’d said her name.

“Only one,” she said. “But I don’t know how to pronounce it.”

“What’s it mean?”

“World-weariness.”

“Ah, weltschmerz,” he said, smiling. “You have that word written all over you.”

“Thanks.”

He was beaming at her again. Where had he come from? He was too open and unguarded to be a native New Englander. She asked him where he was born.

“Germany,” he said.

According to his adoption papers, his birth mother was a French teenage prostitute living in Berlin. An elderly American couple adopted him as a toddler and brought him to their dairy farm in New Hampshire.

“They would’ve been better off adopting a donkey,” he said. “My mother was a drunk and my father danced on my head every other day.”

He ran away with the circus when he was seventeen. Got a job shoveling animal shit and worked his way up to drug procurer. It wasn’t your ordinary circus, though. It had all the usual circusy stuff, but everyone was gay: the owner, all the performers and clowns, the entire crew. Even the elephants were gay.

“What about you?” she asked.

“Straight as an arrow,” he said. After a short silence he asked, “Why, are you?”

She made a so-so motion with her hand.

“Wishy-washy,” he said. “You really are from L.A.”

She laughed.

“Well, I’m glad we got our sexual orientation cleared up,” he said. “Listen, there’s something else I need to get out of the way. Our future together depends on your reaction to this.” He smiled nervously.

“Fire away.”

She was ninety percent certain he was about to tell her he was positive.

But he didn’t say anything, just continued smiling at her, his upper lip twitching with the effort. She smiled back.

“What is this — a smiling contest?” she asked.

“Sort of,” he said.

“You win,” she said.

“Take a good look,” he said.

“Yeah, I’m looking. I don’t see anything.”

He walked over to the sink and filled a glass with water, and then he removed his teeth and dropped them into the glass.

“I’ve read Plato, Euripides, and Socrates, but nothing could have prepared me for the Teeth Police,” he said.

He held up the glass. The teeth had settled into an uneven and disquieting smile. She felt a sudden rawness in her throat, as if she’d been screaming all night.

“They’re grotesque — don’t think I’m not aware of that. I call the top set the Cathedral of Notre Dame. Notice the massive dome and flying buttresses.”

She smiled. The lump in her throat had shrunk, allowing her to swallow.

“What I really need to do is have the roof cut out of the damn thing. There’s this weird suction thing going on whenever I wear it.”

“It cleaves to the roof of your mouth,” she managed, and held her hand up for a high five.

“Precisely,” he said, slapping her hand. “Very uncomfortable.”

He set the glass on the sink and sat on the bed again, gazing distractedly out the window. She realized he was giving her a chance to study his face. He looked better without the teeth-more relaxed, more like himself somehow.

“Well,” she said. “It’s not like I’ve never seen false teeth before.”

“Yeah, but have you been in love with someone who has them?”

She felt her eyes widen involuntarily. “Who says we’re in love?”

“I do,” he said.

For the first time since setting foot in the building, she felt a twinge of fear. She imagined him throwing her onto the bed, gagging her with one of his socks.

“I’m kidding,” he said.

“How old are you?” she asked, changing the subject.

“Forty-four,” he said.

“I might be too young for you,” she said. “I’m only twenty-three.”

“That isn’t too young for me,” he said seriously.

“Of course it isn’t,” she said, and laughed. “What I’m trying to say is that you might be too old for me.”

He frowned. “I had a feeling the dentures would be a deal breaker.”

“It’s not that,” she said quickly. Or was it? She imagined him sucking on her nipples like a newborn, and then waited for a wave of repulsion to wash over her. Instead, she felt oddly pacified and comforted by the image, as if she were the one being breast-fed. “I’m thirsty,” she said.

He made Mexican hot chocolate with a shot of espresso. They sat side by side on his bed, sipping in silence. She noticed a notebook lying on the bed and resisted the urge to pick it up. He saw her looking at it. “That’s the notebook I write snatches of poetry and ridiculous ideas in,” he said.

“Good to know.”

“Do you have anything embarrassing you want to show me? A bad tattoo, perhaps?”

“My parents gave me away to a practical stranger, so my fear of abandonment feels sort of like a tattoo,” she said. “On my brain.”

He smiled. “You visit them?”

“Dad, never. Mom, rarely.”

Rather than a photo, Mona kept a list of her mother’s phobias in her wallet. She was afraid of the usual stuff — death, beatings, rape, Satan — but these commonplace fears were complemented by generalized anxiety over robbers, Russians, mirrors, beards, blood, ruin, vomiting, being alone, and new ideas. She was also afraid of fear, the technical term for which was phobophobia, a word Mona liked to repeat to herself, like a hip-hop lyric. Whenever Mona longed for her, or felt like paying her a visit, she glanced at that list, and then thought of all the pills and what happened to her mother when she took too many, and the feeling usually passed.

“My parents are addicts,” she said and yawned. “But I shouldn’t talk — I’ve been on my share of drugs. Psychiatric.”

“Antipsychotics?”

She laughed. “Antidepressants.”

“No shame in that,” he said. “I’m on four-hundred grams of Mellaril. My doctor said I could develop something called rabbit syndrome, which is involuntary movements of the mouth.” He twitched his mouth like a rabbit, and she laughed.

“What’re you taking it for?” she asked.

“Opiate withdrawal,” he said. “But they usually give it to schizophrenics.”

She nodded, unsure of what to say. He grinned at her and suddenly lifted his T-shirt with both hands. On his chest, a large, intricate, black-and-gray tattoo of an old-fashioned wooden ship with five windblown sails. The Mayflower, maybe, minus the crew. Above the ship, under his collarbone, a banner read “Homeward Bound” in Gothic script.

“Wow,” she said.

“One of the many useless things I purchased with my insurance money,” he said.

“Well, this is kind of embarrassing,” she said, “but I have some pretty big muscles. My biceps and calves are totally jacked. When I wear a dress — which is never — I look and feel like a drag queen.”

“Let’s see,” he said.

She hesitated and then pushed up her sleeve and made a muscle.

“What are these?”

He was pointing to the scars on her upper arm. They were so old she didn’t even see them anymore, but she looked at them now. There were four in that spot, about two inches long each. The cutting had started her sophomore year, immediately following her first dose of rejection by a boy she’d met at a Circle Jerks show.

“Teenage angst,” she said.

“Ah.”

“Maybe that’s more embarrassing than the muscles.”

He made a sympathetic noise and traced one with his finger. Usually she flinched whenever someone touched her arm, but she liked the feel of his hand. She felt something shift inside her — a gentle leveling, as if she’d been slightly out of plumb her whole life without knowing it.

He squeezed her bicep. “Are you a gym rat, love?”

“God, no,” she laughed. “I vacuum. I’m a cleaning lady.”

He blinked at her. “What — like a janitor?”

“Residential.”

“So you clean… houses.”

“Two or three a day,” she said. “In Belvidere, mostly.”

“You clean for a bunch of rich turds,” he said, finally wrapping his head around it.

“Basically,” she said. “Why the surprise?”

“I just think you’re a little above that kind of thing. Seems like a waste.”

She shrugged. “I’ve always felt a weird affinity for monotony and repetition.”

In fact, vacuuming was among her favorite activities. On applications she listed it as one of her hobbies. Even as a child she preferred vacuuming over things like volleyball and doll play. Her classmates had been forced to learn the cello and violin, but her instrument, and strictly by choice, had been a Hoover Aero-Dyne Model 51.

As a teenager she developed a preference for vintage Eurekas. Now she owned four: models 2087, 1458, an Electrolux canister vacuum, and a bright-red, mint-condition Hot Shot 1423, which she christened Gertrude. She’d found Gertrude in a thrift store. Love at first sight.

“Anyway, I’d much rather push Gertrude around someone’s house than sit in a generic office all day. I’ve always felt very relaxed in other people’s homes, and I like the intimacy involved, even though it’s not shared — these people don’t know the first thing about me. But yes, the rich turds, as you call them, can be a bitch to work for — it’s true. I think many of them struggle with the, uh, intimacy.”

“Why — are you sleeping with them?”

“Of course not,” she laughed. “I never see them. Many of them I’ve never met in person. But I know as much as a lover might — more, maybe — and they seem to resent me for that.”

“Ah,” he said. “You’re a snoop.”

“I’m thorough,” she said. “And… observant. You learn a lot about a person by cleaning their house. What they eat, what they read on the toilet, what pills they swallow at night. What they hold on to, what they hide, what they throw away. I know about the booze, the porn, the stupid dildo under the bed. I know how empty their lives are.”

“How do you know they resent you? Do they leave turds in the toilet?”

“They leave notes,” she said. “To keep me in my place. Funny you mention toilets — yesterday a client left me a note that said, ‘Can you make sure to scrub under the toilet rim? I noticed some buildup.’ And I was like, Oh wait a minute, are you suggesting I clean toilets for a living? Because I’d totally forgotten — thanks.”

He scowled. “I’m glad I don’t have to work for assholes.”

“Why don’t you?” she asked.

He smiled and told her he made his living as a thief.

Awesome, she thought. Well, he lived in a hotel so he was definitely small-time. She pictured him running through the streets, snatching purses.

“You don’t take advantage of old ladies, do you?” she thought to ask.

“I do, in a way,” he said matter-of-factly. “I mean, sometimes I do.”

“Well, are you going to elaborate, or do I have to guess?”

“I work for a flower distributor,” he said. “I supply him with pilfered flowers.”

“You’re a flower thief?” Now it was her turn to be baffled.

“That’s right. It’s seasonal work.”

Well, it explained the dirt under his fingernails and the scratches on his hands and arms.

“It’s hard work,” he said. “There’s a lot of driving and sneaking around. And I have to work the graveyard shift, obviously.”

“What kind of flowers do you steal?”

“Hydrangeas, mostly. Blue hydrangeas.”

“You just wander into people’s yards?”

He nodded. “Just me and my clippers! I can wipe out a whole neighborhood in under an hour,” he said, clearly pleased with himself.

She thought of the hacked bushes she’d seen in the Stones’ yard last week. “I think I’m familiar with your work, actually,” she said. “So what do you steal in the winter?”

“Why not ask me in December?” He winked.

“How’s the pay?”

“The guy I work for is a friend of mine. He pays me under the table for the hydrangeas, but he also keeps me on the payroll so I get benefits. It’s like a real job. Anyway, don’t look so upset. It’s not like I’m stealing money. They grow back.”

Against her better judgment, which had left the room hours ago and was probably on its way to the airport, she hung around. They continued talking and swapping war stories, sitting side by side on the bed. By the time the streetlights came on, he took the liberty of leaning in for their first kiss. It was just as she’d imagined it all those months-dry, sweet, a little on the solemn side.

It was like dating a recent immigrant from a developing nation, or someone who’d just gotten out of jail. They went out for dinner and a movie, usually a weekly occurrence for her, but Disgusting’s first time in over a decade. The last movie he’d seen in the theater was The Deer Hunter. At the supermarket she steered him away from the no-frills section and introduced him to real maple syrup, fresh fruit, vegetables not in a can, and brand-name cigarettes. He showed his thanks by silently climbing the fire escape at dawn, after his flower deliveries, and decorating her apartment with stolen hydrangeas while she slept. Easily the most romantic thing anyone had done for her, ever.

Besides the flowers, his first significant gift was a series of drawings he found in the basement of a condemned house. There were seven in total, about five by seven inches each, loosely strung together in the upper-left corner with magenta acrylic yarn. They were crudely drawn in black and red crayon, seemingly by a child. She liked them instantly but was much more fascinated with the captions scrawled across the top of each one. The captions read:

There was a house

A little girl

Two dogs

One Fat Fuck

It was a nice skirt

Fat Fuck was found with no hands

Fat Fuck is dead

He thought the best place to display them was the bathroom. “It’ll give us something to contemplate on the can,” he said. “We can come up with Fat Fuck theories.”

They decided to hang them side by side above the towel rack, and she stood in the doorway, watching him tap nails into the wall. She’d never been in a relationship with someone who owned a hammer. He was wearing a pair of checkered boxers and his Jack Kerouac T-shirt, which had a picture of Kerouac’s mug on the front, along with the caption “Spontaneous Crap.” He’d made the shirt himself and usually wore it during the annual Kerouac Festival, when Kerouac’s annoying friends and fans descended upon Hole to pontificate about the Beat Generation. He called himself president of the I-Hate-Jack-Kerouac Fan Club.

His teeth, she noticed, were resting on top of the toilet tank. As usual, the sight of them produced a buzzing in her brain, like several voices talking over one another. She wanted to put them back in his mouth, or in a jar, the medicine cabinet, a drawer. They needed some kind of enclosure.

“Ever been with a fat guy?” he asked.

She told him yeah, she’d gone to the prom with a fatty named Marty, a funny and friendless guy she knew from art class. He’d been a couple years older than her and, at age seventeen, had already been to rehab twice. Since his license was suspended, his mother had driven them to the prom in her Oldsmobile, and they’d sat in the backseat as if it were a limo.

“Did you wear a dress?” he asked.

“I did,” she said. “It was black and made of Spanish lace. I found it in a thrift store. It came with a veil, but Sheila wouldn’t let me wear that. In fact, she insisted I wear this really gay red flower in my hair.”

“I bet you looked like a hot tamale,” he said.

“I’ve always wanted to be more Spanish,” she admitted.

“How Spanish are you?”

“A quarter.”

“How was it being with a fat guy?” he asked. “Were you on top?”

She rolled her eyes. “Never happened.”

“Did you get loaded?”

“We split half a gallon of chocolate milk on the way there. Then he had a panic attack, so I fed him some of my Klonopin.”

He scratched his beard. “We should start a band called Klonopin.”

She brushed by him and retrieved an old canning jar from under the bathroom sink. She filled it with water and then dropped the dentures into the jar and placed it on the counter, next to her toothbrush. When she looked at him she was startled to see tears in his eyes.

“What’s wrong?”

“Nothing,” he said.

“It’s just a jar.”

He shook his head. “You’re the first woman to touch my teeth without wincing.”

“I clean toilets for a living,” she reminded him. “It’s hard to make me queasy.”

“Makes me want to marry you.”

She laughed. He’d been saying that a lot lately.

If only their sex life were less difficult. He referred to his organ as either “a vestigial, functionless appendage” or “the saddest member of the family.” As for hers, he paid it a lot of attention and talked about it as if it were his new favorite painting — how young and fresh; what extraordinary color and composition. “You have the most beautiful pussy I’ve ever seen in person,” he marveled. “And I’ve seen dozens. You can’t imagine the shapes they come in.” Since he’d taken care to qualify the compliment with “in person” — obviously, he’d seen more beautiful pussies in print or on film — she thought it must be true, and it popped into her mind randomly and without warning, while cleaning out someone’s refrigerator or vacuuming under a bed.

He made love to her primarily with his hands and mouth — like a woman would, he said — and also with his voice. She wasn’t read to as a child, which he considered an outrage, and so, after sex — or sometimes before — he read to her from Kipling’s The Jungle Books (his choice), which suited his voice perfectly, because if wolves could talk they would sound just like him, and then short stories by Hemingway, whom he called Uncle Hem, and Flannery O’Connor and Chekhov and some other people she’d never heard of.

On Sundays they climbed the fire escapes of the abandoned mills downtown — their version of hiking — and rolled around on the rooftops. If the weather was nice they smoked cigarettes and took black-and-white photographs of each other with her old Nikon. After one such expedition near the end of August, they were walking back to her apartment when Disgusting veered toward a large pile of garbage someone had left on the street.

“Mind if I sift through this stuff ?” he asked.

She waited on a nearby stoop. She heard someone exit the building behind her and blindly scooted over to let the person pass.

“Mona,” a voice said.

It was Janine Stromboni, an old acquaintance from high school, one of the few girls Mona had liked, even though they’d had zero in common. Janine looked much the same: huge hair, liquid eyeliner, fake nails, tight jeans.

“Wow,” Mona said. “You live here?”

“Just moved in,” Janine said, and sat down. “You still smoke?”

Mona fished two out of her bag and lit them both before passing one to Janine. They chatted for a few minutes and then Mr. Disgusting waltzed up carrying a green vinyl ottoman.

“A footrest for my footsore princess,” he said and gallantly placed it at her feet.

She introduced Disgusting to Janine. To Mona’s relief, he looked good that day, like your average aging hipster. He had a tan, recently dyed black hair, and was sporting a Mexican cowboy mustache. His denim cutoffs were a little on the dirty side, but his shirt was clean, and Janine would never know the shoes he was wearing had been retrieved from a Dumpster.

Janine, however, looked plainly disgusted by Disgusting, and for a split second she saw him through Janine’s eyes: an old dude with dirty hair and no teeth, what Janine would refer to as a “total creature.”

Janine bolted right after the ciggie. The encounter permanently altered Mona’s perception of Disgusting, and from that day forward, depending on the light and her angle of perspective, he alternated between the two versions — aging hipster, total creature, aging hipster, total creature — like one of those postcards that morphs as you turn it in hand.

Her feelings for him, however, didn’t change. If anything, she grew more attached. Like cancer, he had a way of trivializing the other aspects of her life. Things that had previously seemed important were now pointless and absurd, her college career in particular. So, when the time came to register for the fall semester, she blew it off. Her major, studio art with a concentration in photography, seemed like a joke now, especially in busted and depressing-as-hell Hole. If she was going to study art, she reasoned, didn’t it make more sense to go to a real art school in a city that inspired her?

“Fuck art school altogether,” Disgusting said. They were in bed, wearing only their underwear and listening to his collection of psychedelic records, which he’d brought over to her apartment on their fourth date and to which they’d been dancing ever since. Dancing, Disgusting maintained, was the key to salvation.

“I can see going to college for math or science,” he said. “But art? Waste of time. All you really need is persistence and good taste, which you already have. The other junk you can pick up from books.” He smiled and slipped his hand into the front of her underpants. She was wearing one of her days-of-the-week underwear, the green nylon ones with yellow lace trim, the word “Wednesday” stitched across the front in black cursive. It was Friday.

“You smell different today.” He removed his hand and thoughtfully sniffed his fingers. “You smell like… hope.”

“What do I usually smell like — despair?”

“Like a river,” he said. “A little-known river in Latvia.”

She pulled at the waistband of his boxers, but he stopped her. “Let’s leave my genitals out of this.”

“Why?”

“Too sad and disappointing.”

“But I like your sad and disappointing genitals,” she assured him. “Besides, they wouldn’t be so sad if you weren’t so mean to them.”

He kissed her hand and placed it on his chest and she traced the words “Homeward Bound” with her finger. “Move in with me,” she heard herself say.

He was silent for a minute. “I’m pretty high maintenance right now.”

“I can handle it.”

He cleared his throat. “Let’s embrace our lone-wolf status. Few people have what we have, which is true and total freedom. No parents, siblings, spouses. No offspring. Nothing to tie us down. We can roam the earth and never feel guilty for leaving anyone behind, for not living up to someone else’s expectations.”

“Sounds lonely,” she said.

“Don’t think of loneliness as absence. If you pay attention, it has a presence you can feel in your body, like hunger. Let it keep you company.”

“That’s not the kind of company I want.”

He kissed her mouth. “We’re lucky we found each other,” he said. “Two orphans.”

She visited him in his room at the Hawthorne twice a week. Once, after a reading session, he excused himself to go to the bathroom, located down the hall, and while he was gone she heard someone tap on his door with what sounded like acrylic fingernails.

“It’s me,” a female voice sang out.

Mona opened the door to a shapely woman with a pretty face and a crazy look in her eye. She looked American-Indian — brown skin, tall nose, long black hair parted down the middle — and was wearing a red button-down blouse with open-toed stilettos half a size too small. She’d apparently forgotten to put pants on, but had had the presence of mind to wear underwear. Mona wondered whether she was a prostitute, insane, or both.

“Is he here?” the woman asked.

“He’s in the bathroom,” Mona said.

“Are you a cop?”

“No.” Mona snorted. “Why, do I look like a cop?”

“Sort of.”

“Well, I’m not,” Mona said.

“Just slumming then, I guess,” the woman said, but not unpleasantly.

She shrugged. You may have bigger tits than I do, she thought, but otherwise we’re not so different. We both have jobs that require us to work on our knees.

“Well, tell him I came by,” the woman said as she walked away.

When Mr. Disgusting came back he launched into a story about his near suicide in Oaxaca, where he’d planned to shoot himself in the head with a gun he’d purchased in Mexico City, but had been too distracted by the scorpion on his pillow —

“Do you have a date tonight?” she interrupted.

“What?”

“Some chick came by looking for you.”

“What’d she look like?”

“A pantless Pocahontas.”

“Roxy,” Disgusting said. “She’s a sweetheart. You’d really like her.”

“Is she your girlfriend or something?”

“God, no,” he said. “I look after her and a couple of her friends.”

There was a silence while she turned this over in her mind. “Are you telling me you’re a pimp?” she asked. “Because that would be worse than having no teeth. Much worse.”

“I prefer ‘Gangster of Love,’” he said, somewhat smugly.

“Terrific.”

“It’s not what you think,” he said. “Since I work nights, I let them use my bed, provided they change the sheets. I give them a clean, safe place to conduct business. I consider it an act of kindness.”

“What do they give in return?”

“Beer money, actually.” He raised his shoulders in a so-sue-me gesture.

“But you’re sober now,” she reminded him.

“I know,” he said. “Look, this isn’t Taxi Driver, okay? These girls aren’t twelve years old. I’m not the one turning them out. They’d be doing it anyway, only they’d be out God knows where, in the back of a van — ”

“Dating a pimp isn’t what I envisioned for myself at this point,” she interrupted. “At any point,” she corrected herself.

“All I ask is that you try not to judge me.”

She sat there for a minute, trying.

“You can leave if you want,” he said. “I’m not holding you hostage here. We could end this right now, in fact. But I don’t think we’re done with each other yet, do you?”

“No,” she said morosely.

“Look, I’ll start packing tomorrow,” he said. “Okay? I’ll move in next week.”

Two days later, in the middle of a Thursday night, he called and said he was having trouble reading the writing on the wall. She knew what he meant, and replied that she, too, couldn’t always see what was right in front of her. She needed some distance from it, space —

“No, Mona, there’s actual writing on the wall, but I can’t read it,” he interrupted. She heard panic in his voice. “It’s only there when I turn the lights off and I hold a flashlight to it.”

“What’s it look like?” she asked.

“Like a swarm of bees, scribble-scrabbling.”

“Scribble-scrabbling?”

“Yeah, like, protecting the queen,” he said.

“Are you on mushrooms?”

“It’s ballpoint ink, strangely enough,” he continued, ignoring her. “Red

ballpoint.”

“Well, is it cursive, or what?” she asked, at a loss.

“Yeah, only it’s swimming backwards. It’s indescribable, really. Could you come over? Just for five minutes? I’m freaking out.”

She sneaked into the back of his building, ran up the stairs, and let herself in with the key he’d given her. He was passed out on his back with his mouth ajar, naked except for a hideous turquoise Speedo, clutching a flashlight against his chest like a rosary. She looked at the walls: nothing there, of course.

She figured he took one Mellaril too many, but in his nightstand drawer she found a dirty set of works surrounded by dirty cotton, and her head started spinning. His arms were bruise-free, but his hands and feet were swollen and she saw the beginning of an abscess on his ankle. He must have been putting it in his legs or feet. Fuck!

His notebook was lying open on his pillow and she read the open page:

I have renewed my travel visa to my favorite island. Now I can come and go without being stopped by the border police and accused of trespassing. It is pathetic how much I’ve missed this island’s scenery, its exotic food, its flora and fauna. Tonight I am in my little plane, flying around the island’s perimeter. To amuse myself, I perform tricks: triple corkscrews and low, high-speed flybys — my version of a holding pattern. But I’m running out of gas. The engine keeps cutting in and out, making little gasping noises. I’ll probably crash any minute now.

She was offended that she didn’t see her name in his diary. She tried nudging him awake, but he was out cold. No point in hanging around. She didn’t want to leave, though, without him knowing she’d been there. Rather than write a note, she removed her left shoe and then her purple sock, and slipped the sock over his bare foot. He flinched but never opened his eyes.

Over a week passed. He didn’t call and wouldn’t answer his phone. She waited for her back to go out, which was usually how her despair chose to manifest itself, but instead she became suddenly and bizarrely noise sensitive. At the supermarket she was so overwhelmed by the noise she had to clamp her hands over her ears and hum to herself, sometimes abandoning her shopping cart. After an embarrassing incident at Rite Aid, wherein she asked a woman if there was any way the woman could quiet her baby, who wasn’t even crying, just cooing, she had the bright idea to purchase earplugs, and took to wearing them whenever she left her apartment.

At work she raided people’s refrigerators, often taking breaks in the middle of the day to eat and lounge around in their living rooms, reading magazines or watching television. When there was nothing to eat, she raided medicine cabinets. Xanax, Valium, Vicodin, Darvocet — only one or two of whatever was on the menu, enough to take the edge off and still be able to vacuum. She’d always had a snooping policy — No Letters, No Diaries — but when she was high and itchy she read people’s diaries and personal papers. She read them hungrily, even if they were boring. And they were almost always boring. Afterward, she felt nauseated and ashamed, as if she’d eaten an entire birthday cake and then masturbated on their bed.

It was while reading Brenda Hinton’s weight-loss diary — full of body measurements, scale readings, and daily calorie intakes — that she finally broke down. That is, she had a coughing attack, which triggered a gripping back spasm, the likes of which she’d never felt before. She fell to her knees and lowered herself the rest of the way to the floor, where she lay for twenty minutes or so, staring at a water stain on the ceiling while Brenda Hinton’s dog, a miniature schnauzer with an underbite, calmly licked her elbow. Eventually she reached for the phone and called Sheila in Florida.

“What’s the matter?” Sheila asked.

“Back,” she said. “Muscle spasm.”

“Yoga, honey,” Sheila said.

“The downward dog isn’t going to help right now.” The schnauzer seemed to roll his eyes at her. She decided she didn’t like dogs with bangs.

“I never hear from you. What’s going on?”

She spilled the beans: she’d fallen for an addict, someone she met at the needle exchange. They were in a relationship. Yes, a romantic one. He’d been sober for six months. Now he wasn’t. “Blah, blah,” she said. “You’ve seen the movie a million times.”

To her relief, Sheila didn’t offer any banal Freudian interpretations.

“Maybe now you’ve finally hit bottom,” Sheila sighed. “I know you won’t go to Al-Anon, but it’s time to get on your knees and start talking to your H.P.”

“What’s that again?”

“Higher Power, babe.”

“Right,” she said. “Small problem: I don’t believe in God. As you know.”

“What happened to Bob?”

Bob had been her nickname for God when she was a child. She’d talked to Bob like an invisible friend. She’d mentioned this to Sheila in passing once, years ago, and Sheila never forgot it.

“Bob’s dead,” Mona said. “Prostate cancer.”

“He’s not dead, sweetie,” Sheila said sadly. “But forget about Bob. Your

H.P. can be anyone. It can be John Belushi or Joan of Arc or Vincent van Gogh. In fact, Van Gogh might be perfect for you. He was tortured by his emotions, never received positive feedback, and died without selling a single painting. If his spirit is out there, it can relieve you of your suffering. So, start now. Get on your knees and ask Vincent for help.”

She took three days off work, two of which she spent resting her back. On the third day she hobbled to the Hawthorne and let herself into his room. He was in the same position as last time, lying diagonally on his bed and wearing only his underwear. His room was trashed: he’d stopped doing laundry, emptying ashtrays, taking out the garbage.

She waved her hand in front of his face, snapped her fingers. He opened his eyes momentarily and whispered, “I’m gonna put my boots on and make something happen.” Then he nodded out again. She envied the blankness on his face.

Her presence never fully registered with him and she sat in the corner for twenty minutes, feeling as invisible as a book louse. It was worse than the way she felt at work, passing in and out of rooms, a ghost carrying a cleaning bucket.

Again, she wanted to let him know she’d been there. She removed an earring and placed it on his nightstand, along with some items from the bottom of her purse — a broken pencil, a ticket stub to a Krzysztof Kieślowski film, several sticky pennies.

It became a kind of ritual. Over the next several weeks she visited his room and left behind little tokens of herself: his favorite pair of her underwear, a lock of her hair, a grocery receipt. When she was feeling bold, she tacked a picture of herself onto the wall near his bed. But now he was never there when she was. She figured he was out and about, making something happen somewhere. Still, leaving the items made her feel less adrift, less beside the point. In fact, she was amazed by how much a few minutes spent in his room — marking her territory, as it were — seemed to straighten her out.

One day he surprised her by being not only there, but awake and lucid. She hadn’t seen him in three weeks and was startled by the amount of weight he’d lost, particularly in his face — his eyes were what they called sunken — and by the fullness of his beard, which he tugged on now as he sat on the edge of his unmade bed.

“Are you here to deliver one of your voodoo objects?”

She shrugged, embarrassed. “I guess I’m worried you’ll forget me.”

He nodded thoughtfully, as if she’d just said something really interesting. She noticed the loaded syringe parked on his nightstand, waiting for takeoff. “Looks like I’m interrupting your routine,” she said.

“I can wait until you leave.”

“Pretend I’m not here,” she said and felt her chin tremble. She’d missed his voice, his anecdotes, his eyes on her.

“I have to hop around on one leg to find a vein these days. It’s humiliating enough without an audience.” Apparently the feeling wasn’t mutual; he didn’t miss her eyes on him, or anything else about her. In fact, he barely looked at her. She sat down in the armchair.

“Why’d you relapse? Is it because we’re moving in together? If it freaks you out that much, we don’t have to do it.”

He shook his head. “It’ll sound stupid to you.”

“Try me,” she said.

He pursed his lips, shook his head again.

“What’s with the sudden reticence?” she asked. “I thought you were the show-and-tell type.”

He crossed his legs, lit a cigarette, blew smoke toward the ceiling. If she were one of those willful, high-maintenance girls, she’d be throwing a tantrum right now — stomping her feet, interrogating him, demanding answers. But then, a high-maintenance girl never would have set foot in the building in the first place, wouldn’t even be seen in the neighborhood. “You know, you’re lucky I’m so easygoing,” she said, stupidly.

“It was free,” he said after a minute. “And it hadn’t been free in twenty years. It’s hard to say no when something is free, especially for someone like me.”

“That’s your excuse?”

“It’s really as simple as that,” he said. “It has nothing to do with you.”

“Is that all you have left?” she asked, nodding toward his nightstand.

“For now,” he said.

“If I buy some more, can we do it together?” she asked. “I have a wicked backache.”

He studied her face for several seconds, finally acknowledging her, but it was quickly followed by indifference and his gaze returned to the floor.

Since he’d apparently chosen drugs over her, even after everything she’d shared with him — her mattress, her secrets, her so-called beautiful whatsit — it seemed only fair that she know what she’d been up against. She pulled forty dollars from her wallet. “Is this enough?” she asked,

placing the money on the bed.

“Cut it out,” he said, rolling his eyes.

“I’m serious,” she said.

He picked up the syringe and held it in front of her face. “This is this,” he said emphatically. “It isn’t something else. This is this.”

She blinked at him. “Is that a line from a movie?”

He crossed his arms. “Maybe.”

“You’re being slightly grandiose,” she said. “You know that, right?”

“Yeah, well, you’re not taking this shit seriously enough,” he said.

Twenty minutes later, they were sitting on his bed and he was inserting his only clean needle-the loaded one on his nightstand-into her arm. “That syringe looks really… full,” she said, too late.

“Believe me, it’s barely anything,” he assured her.

The next thing she knew she was lying on the floor of a stuffy attic. The air smelled like pencil shavings. A fan, some high-powered industrial thing, was on full blast, making a loud whirring noise and blowing a thousand feathers around. It was like the Blizzard of ’78. Then the fan clicked off and she watched the feathers float down, in zigzaggy fashion. They landed on her face and neck and she expected them to be cold but they were as warm as tears, and that’s when she realized she was crying and that the feathers were inside her. So was the fan. The fan was her heart. A voice was telling her to breathe. She opened her mouth and felt feathers fly out. There was a rushing noise in her ears, a mounting pressure in her head, a gradual awareness that something was attached to her. A parasite. She was being licked, or sucked on, by a giant tongue, a wet muscle. The sucking sensation was painful and deeply familiar, but there was no comfort in the familiarity, only dread, panic. She felt herself moving, flailing, trying to get away from it.

When she opened her eyes she felt a presence next to her on the bed. An exhausted female presence. She gasped, turned over, and found Mr. Disgusting sitting on the edge of the bed, scribbling in his little notebook.

“Ah, you’re back,” he said. “You had me worried for a minute.”

She tasted blood in her mouth. “Did something… happen?”

He closed his notebook, placed his pencil behind his ear. His pupils were pinned. “I lost you for a few minutes.”

“I passed out?”

“I think you must be allergic to amphetamines.”

“What?”

“You have a cocaine allergy,” he said patiently, as if he were a doctor. “You’re probably allergic to Novocain, too. And caffeine, maybe. Does coffee make your heart race?”

“I thought we were doing… heroin.”

“I mix them together,” he said. “I mean, nothing major — just a little pinch. It was meant for me, not you, and I’d forgotten about it.”

“Where are my boots?” she asked.

“You looked like a half-dead fish lying on the pier, just before it gets clobbered.”

“So what,” she said. “Who gives a shit?”

“I do,” he said. “That’s why I took such careful notes. I knew you’d want to know exactly what happened.”

“So what if I died while you were taking notes? You’re obviously too wasted to take me to the hospital.”

“Since when do you care about dying? Besides, I knew you wouldn’t die die. I was keeping my finger on your pulse the whole time. Your heart stopped beating for about five seconds and then it normalized. Let me ask you something: did you see anything? A white light? A tunnel? Dead people?”

“I was inside a vagina,” she said. “A giant vagina, it felt like, but then I realized it was regular sized and I was just really small.”

He smiled and nodded, as if he’d been there with her. “Whose was it?”

“My mother’s, probably.” She shuddered and hugged herself. “Is it cold in here?”

“You have a really weird expression on your face,” he said.

“Do you realize how shitty it is to be born?”

He did some slow-motion blinking.

“It’s excruciating — physically, I mean. There must be some mechanism in the brain that doesn’t allow you to remember, because if you had to live consciously with that memory… well, you’d never stop screaming.”

“It’s called birth trauma,” he said, nodding. “But I doubt it compares to other kinds of trauma. You know, like slavery. Or torture.” He gave her a significant look, but she was too nauseated to respond. She got out of bed, hobbled down the hall to the bathroom, locked the door behind her. There it was, her stupid face in the mirror.

Where’s your lipstick? she heard Sheila’s voice say. You look like hell. Why don’t you get on your knees — right here, right now — and talk to your H.P.?

She was on her knees two minutes later, vomiting into the already — filthy toilet. Puking was easy, almost pleasurable — like sneezing. She flushed, examined the ring around the bowl, imagined herself dumping Comet into it, scrubbing with a brush, spraying the lid with Windex, wiping it clean with toilet paper, moving on to the rest of the toilet-the tank, the trunk, the floor around it —

Detach, she ordered herself. Observe. Observe the dirt.

Someday, hopefully, she’d be able to enter a bathroom, even on drugs, and not envision herself on her hands and knees, scrubbing the baseboards with a damp sponge —

And that’s when she noticed Mr. Disgusting’s handwriting right next to the light switch:

If we had beans,

we could make beans and rice,

if we had rice.

Back in his room, he was still in bed, propped up against the filthy wall with a belt around his arm. His body was slack, his eyes half open. She wondered if he’d had more dope all along, or if he’d gotten it from one of his neighbors while she was in the bathroom.

“Sometimes I wish I were made of clay,” he mumbled.

He was miles away now, in his little plane, she imagined, flying around his favorite island. She put her boots on and he opened his eyes and said, “No, no, no — stay.” He patted the space next to him on the bed. “I’ll read you a story. Chekhov. ‘The Lady with the Dog.’”

“I’m sick of stories.”

In fact she felt a little like Anna Sergeyevna right now, after she and Gurov have sex for the first time. Disgraced, fallen, disgusted with herself. Aware that her life is a joke. Anna gets all moody and dramatic, but Gurov doesn’t give a fuck, and just to make it clear how bored he is by her display, the watermelon is mentioned. There it is on the table. He slices off a piece and slowly eats it, and thirty minutes tick by in silence.

Mona laughed.

“What’s funny?”

“That’s who you remind me of,” she said. “Gurov and his watermelon. You don’t really care about me. I’m just your boring mistress.”

He rolled his eyes. “Aren’t you at least a little high?”

“I read your diary,” she said.

“Of course you did,” he said. “And?”

“I’m not your favorite island.”

“There are better places to be sober,” he said, as if continuing an old conversation. “In the next life I’ll have an Airstream next to the Rio Grande, a silver bullet with yellow curtains. I’ll wash my clothes in the river and hang them on a clothesline. I’ll have vegetables to tend, books to read, a hammock, a little dog named Chek-”

He nodded off, his mouth still twisted around the word. His voice, she noticed, had lost its teeth. She crept over him on the bed, carefully unbuttoned his pants, worried her hand into his boxers. What the fuck are you doing, she asked herself. He’s gone, you fool. It’s over.