Reading Lists

10 Books That Show the Dark Side of Music Mania

These novels, stories, and memoirs demonstrate the potential, and the danger, of a mind under the influence of music

The English restoration playwright William Congreve has the curious distinction of having written two famous lines, one of which is widely misattributed to Shakespeare and usually paraphrased, “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned,” and the other most often misquoted as “Music hath charms to soothe the savage beast.” Both lines are from Congreve’s 1697 play, The Mourning Bride, and the bit about music actually reads: “Music hath charms to soothe a savage breast, To soften Rocks, or bend a knotted Oak.” While the more renowned William hardly needs two more quotable sayings added to his vast catalogue, music did often enter into his plays — its power to soothe (be it a troubled breast or beast) but also to bring about grief. In the opening of Act IV of Measure for Measure, which begins with a song, the Duke assures Mariana that “music oft hath such a charm / To make bad good, and good provoke to harm.”

The capacity for music to provoke harm and drive people mad goes back even earlier in Western literature, when Ulysses is advised by the goddess Circe, in Book 12 of Homer’s The Odyssey, about the Sirens. Sailing by the island of the Sirens, she warns, without being tied to the mast or having one’s ears plugged by wax, will guarantee that no man will ever see home, wife, or children again. “The high, thrilling song of the Sirens will transfix him, / lolling there in their meadow, round them heaps of corpses, / rotting away, rags of skin shriveling on their bones.” One wonders, just what were they singing?

In my novel, The Prague Sonata, music takes center stage as a young musicologist sets out on a quest to locate the missing parts of an eighteenth-century piano sonata manuscript and attempt to identify its composer. For all its sublime joys in the novel, music is also locked in a timeless dance with war and death. Any number of the composers and musicians who are conjured in the book — from Beethoven to Jimi Hendrix to “mad as a March hare” Schumann — paid dearly for their devotion to the musical Muses. And while thinking back over some of my favorite books in which music plays a central role I was struck by how many, whether fiction or not, leaned less toward the soothing than the dark side of music and musicians.

1. Annie Proulx, Accordion Crimes

The green accordion in this sweeping hundred-year narrative provides both the music and the metaphor centering Proulx’s epic of immigrant, often malignant, America. Characters with names like Przybysz and Salazar, Baby and Malefoot, are all at one point or another the owners of the accordion, originally transported in the late nineteenth century by its anonymous maker from Sicily to New Orleans, where he is murdered by an anti-Italian mob. A dizzying, bloody odyssey follows from Mississippi to Montana to Maine and beyond, in which those who own the accordion often encounter racism, hatred, mindless violence, and every so often a ray of gladness brought about by the increasingly dilapidated accordion (which meets its own sad fate in Florida in the book’s final pages). Just as migrants bring with them the richly specific melodies of their homelands, they inevitably, per Proulx’s unflinchingly dark vision of America, encounter those who would deny them their songs, their voices, often their very lives. All brought to life — and death — with the author’s own musically prodigal language.

2. Michael Ondaatje, Coming Through Slaughter

Employing his singular gifts as both a poet and fiction writer, Ondaatje offers a deeply moving, uniquely hybrid collage-style portrait of Buddy Bolden, sometime New Orleans barber at Joseph’s Shaving Parlor and first of the greatest jazz trumpet players, whose sui generis approach to the instrument influenced the likes of Louis Armstrong and King Oliver. In lyrical prose punctuated with documentary facts, Ondaatje evokes the sad life of a gifted, doomed man. Alcoholic, haunted, prone to disappearing, ultimately mad, Bolden was also an incandescent and legendary musician who preferred playing in the key of B-flat and died on November 4, 1931, in the East Louisiana State Hospital. There is only one surviving photograph of him with his jazz band, and there are no known recordings. While Bolden’s breakdown and institutionalization in 1907 may not be directly attributable to his bond with music — in fact, his trumpet probably saved him from himself for a time — it is interesting that during his many years in “the bug house” he stopped speaking and never played another riff, not even a note, on his trumpet.

3. Thomas Mann, Doctor Faustus, The Life of the German Composer Adrian Leverkühn as Told by a Friend

Mann’s postwar masterpiece is one of those necessary epics, like The Magic Mountain, that must be read slowly, savored empathically, in order to fully experience the tragedy of Leverkühn’s syphilitic descent into madness and invalidism that is directly compensated by his exceptional ability to compose transcendent music. After contracting the disease from a prostitute during his only sexual encounter — his symbolic selling of body and soul — Leverkühn grows more ill while at the same time his music is increasing touched by genius. Mann doesn’t shy away from symbolic references to the Faustian deal many Germans made during the rise of the Third Reich, collectively trading their ethics to embrace the deadly extremist nationalism of Nazism. Just as in the original Faustian tale, deals cut with the devil inevitably come to bad ends. While his prose style may be a bit traditionally rigorous for some, the reward is that few other novelists command a greater knowledge of classical music than Thomas Mann.

4. Oliver Sacks, Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain

When the late, very great Oliver Sacks weighed in with one of his psycho-neurological collections of case studies centered on music a decade ago, I couldn’t put my hands on a copy fast enough. Like legions of others, I was fascinated by books like The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, An Anthropologist on Mars, and Awakenings, and now he’d written about a subject dear to my heart. Nor did he disappoint. Here was Silvia N., who suffered from musicogenic epilepsy, a syndrome in which music — in her case the Neapolitan songs from her childhood — provoked seizures cured by a partial temporal lobectomy. Here was Sydney A., a man with Tourette’s Syndrome who “lurched, jerked, lunged, yelped, made faces, and gesticulated exuberantly” upon hearing music on the radio. Here, too, were stories of Martin, whose childhood meningitis contributed to severe physical and mental disabilities, but also contributed to his becoming a musical savant who knew over two thousand operas (who’d have guessed there were so many in the first place?) as well as Bach’s cantatas. If you suffer from earworms — as I do, with sometimes near-pathological severity (I cannot listen to Rufus Wainwright, alas, without it sticking in my head for weeks) — Sacks has a chapter on that as well.

5. Ann Patchett, Bel Canto

The perils of being a famous musician are as inherent as they are various. While fans provide the means for a star-dusted performer to thrive, they also have the capacity, whether purposely or inadvertently, to put their idol in harm’s way. Patchett’s lyric soprano opera star, Roxane Coss, has doubts about accepting the invitation to perform at the birthday party of mega-rich electronics mogul Katsumi Hosokawa in an unnamed Latin American country that’s courting his investment, but the payday is irresistible. As her last aria rises to its conclusion, the lights in the vice-president’s palace abruptly go dark as Coss, Hosokawa, and the rest of the black-tie attendees find themselves swarmed by terrorists. The siege that ensues becomes a palpable opera itself — operas, including soaps, are woven throughout — as it stretches from days to months, enveloping its sizeable cast of captors and captives. Unexpected liaisons develop. Hidden talents are discovered. Violence is never far away (the author gives a particularly unflinching account of Coss’s diabetic accompanist’s death as his insulin runs out). When the siege does inevitably end, ensuing elements of romantic fantasy may dismay some readers, while enchanting others, but the hard edge of Patchett’s detailed portrayals preserve the darkness inherent in this music-saturated novel.

6. Robert Coover, “The Return of the Dark Children” (A Child Again)

Only Angela Carter rivals Robert Coover when it comes to rethinking, reviving, and retelling classic fables and fairy tales. With this adaptation of “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” Coover takes an already grim cautionary tale and moves it to the gloomiest possible registers. The story begins, long after the piper has seduced all of Hamelin’s children away playing his “demonic flute,” with the reappearance of black rats “scurrying shadowily along the river’s edge and through the back alleyways.” The shortsighted, greedy townsfolk, who failed to pay their musically bewitching exterminator, now face a fresh ethical dilemma as a new generation of Hamelin kids are endangered once again. Hysteria grips the village, imaginations run amok. And a déjà vu choice must be made anew “between letting the children go, or living — and dying — with the rats.” Needless to say, as is too often the case with village elders, they opt for the inevitably expedient course of action. Sorry, children of Hamelin. And as for the future, the playing of music will be frowned upon and dancing discouraged. As if all the woes of the world were a piper’s fault.

7. Miles Davis with Quincy Troupe, Miles: The Autobiography

8. Quincy Troupe, Miles and Me

Both jazz legend Miles’s autobiography and poet Quincy Troupe’s memoir, Miles and Me, which offers a disarmingly candid account of their Sturm und Drang relationship, unveil the demons, the mind-blowing contradictory behaviors, the self-confidence and self-hatred, and the very hard-earned genius of one of the greatest musicians of all time, jazz or otherwise. Bitches Brew wasn’t plucked out of thin air. None of Miles’s revolutionary work over the course of decades from the bebop-cool jazz of Kind of Blue to the fusion of Tutu came without profound personal costs. Miles’ drug and alcohol addictions, his distress over the blackness of his skin, his raging diabetes, his volcanic temper, his loneliness behind those wraparound shades — these are only a few of the monsters Miles battled, emerging triumphant on most counts while reinventing, over and over again, that singularly American kind of music: jazz. The biopic film treatment of Miles and Me, by the way, will reportedly be going into production in early 2018 with Michael K. Williams as Miles. I’m so there for that.

9. Lauren Belfer, And After the Fire

In The Prague Sonata, my protagonist recalls her mentor sternly lecturing, “More often than not, music means music. It’s not a poem about a tree. It’s not an essay about nematodes. It often stands for nothing greater or lesser than itself.” Whether one agrees with him or not, sometimes music can be a medium for communicating a message, and there is no guarantee that the message will be benign. In Lauren Belfer’s richly detailed novel, And After the Fire, a lost Bach cantata turns out to have been deliberately kept hidden for centuries after Bach’s eldest son, Wilhelm Friedemann, entrusts the manuscript to his talented piano student, the Jewish socialite Sara Itzig Levy. Shocked by its virulently anti-Semitic message, Sara hides the score and it remains hidden by generations of her family until, by chance, it is rediscovered in the present day. If Martin Luther was the father of the denomination to which Bach belonged — “be on guard against Jews,” Luther wrote in his essay “On Jews and their Lies” — Richard Wagner, one of Adolf’s favored German sons, took up the wicked cause. A bright book about dark hatreds.

10. Richard Powers, Orfeo

Pity Peter Els. All this aging American composer of obscure avant-garde music ever wanted was to “break free of time and hear the future.” And if his innovative path to achieve this goal was to inscribe musical compositions in bacterial DNA at his homemade microbiology lab — where he uses, among other things, a salad spinner for a centrifuge and a rice cooker to distill water — then who would stand in his way? Well, for openers, two Homeland Security goons who show up at his door, looking like “counterfeit Jehovah’s Witnesses,” and begin questioning him, confiscating his equipment, and telling him not to go anywhere. The next day, as government investigators accompanied by a throng of media descend upon his abruptly quarantined house, Els decides to flee. Only a writer with Richard Powers’s rare imagination and technical dexterity could pull off the mad odyssey that follows. Dubbed the “Bioterrorist Bach,” Els unexpectedly finds himself an Internet sensation as he sets out on what is to be his final bit of performance art. When readers turn the last pages of Orfeo, they are fully aware that the Kafkaesque forces closing in on Els will not be deterred. It’s a good moment to remember that Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time was always one of Els’s favorite compositions but that he, unlike Messiaen, will not elude his personal apocalypse.

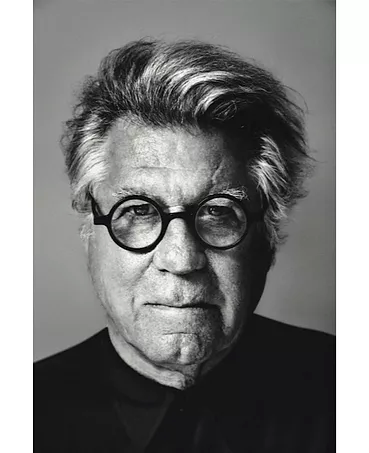

About the Author

Bradford Morrow is the author of eight novels, including Trinity Fields, The Diviner’s Tale, The Forgers, and now, The Prague Sonata. He is also the author of The Uninnocent, a short story collection. He is the editor of Conjunctions, which he founded in 1981. Morrow has received numerous awards and honors, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, O. Henry and Pushcart prizes, an Academy Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the PEN/Nora Magid Award for excellence in editing a literary journal. A Bard Center Fellow and professor of literature at Bard College, he lives in New York City. www.BradfordMorrow.com