Interviews

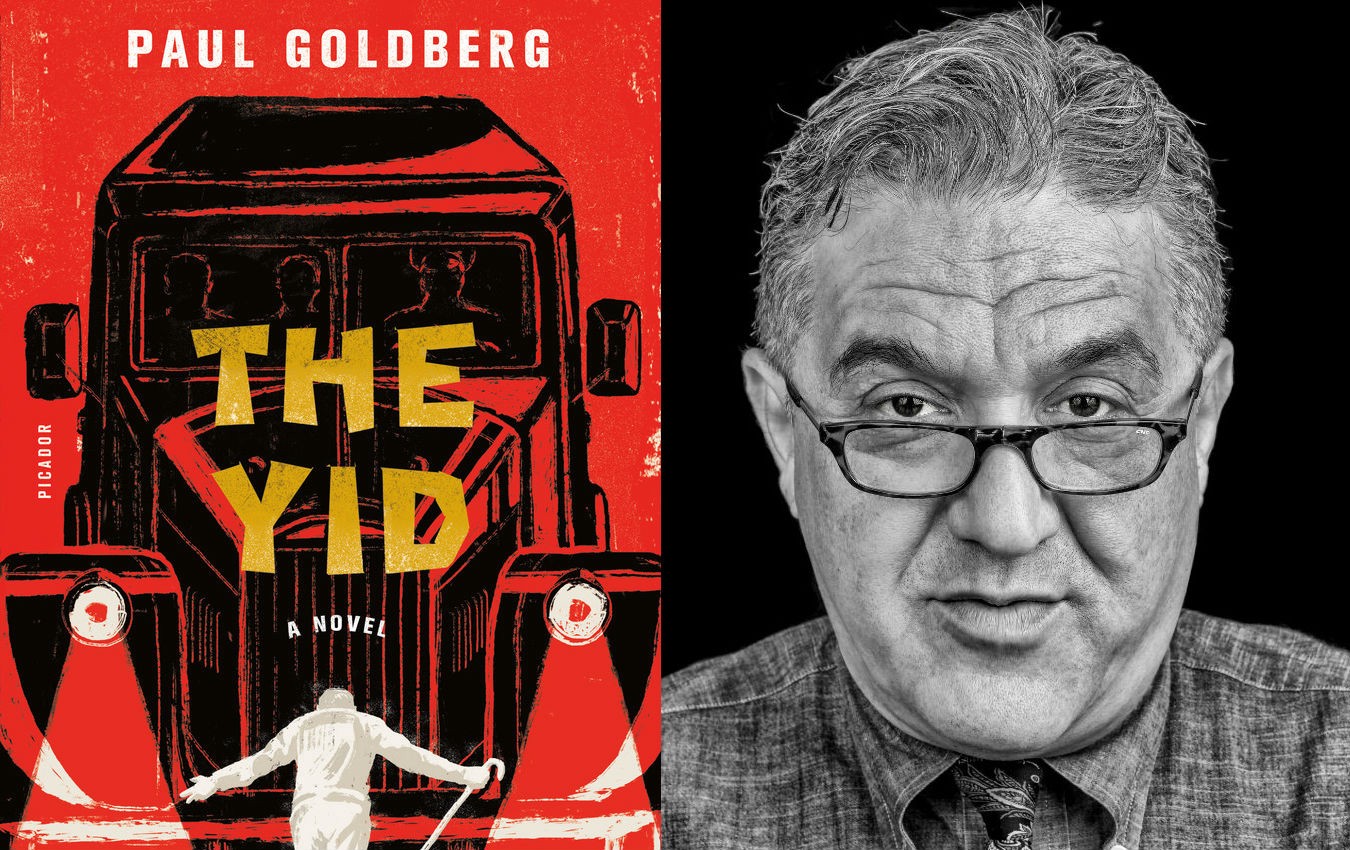

Paul Goldberg, Author of The Yid, Discusses Blood Libel & The Dark Clowns of Stalinist Russia

I talked to Paul Goldberg on a Sunday afternoon at his house in D.C., right by the National Cathedral. He made me herbal tea in a ‘Write Like A Motherfucker’ mug, indulged me while I played with his Australian Shepherd, and showed me some of his Soviet memorabilia, including a flag that once flew over the Soviet embassy to the United States. He says he bought it for $10 at a yard sale.

Goldberg is the author of The Yid (Picador, 2016), a book in which a bunch of elderly Jews led by a retired clown named Solomon Levinson try to assassinate Stalin on the eve of a massive pogrom. Chunks of the text are written in script rather than prose format, and when there’s prose it’s as much history and philosophy as it is fiction. I’ve never read anything like it. Believe me, neither have you.

LM: I want to start by asking about theater. Were you ever in plays as a kid?

PG: Absolutely not. I have no theatrical skill, talents, or abilities. I love theater and I was obsessed with theater as a tool for the novel, but I’ve never been a theater insider of any sort.

LM: Then how did you become obsessed with theater as a tool for the novel? I’ve never read a novel that has scripted action the way The Yid does.

PG: The scripts come from a specific book, and a specific place in the book. There’s a scene in The Tin Drum [by Günter Grass] where they’re running around the Baltic, along the Nazi fortifications. It totally shook me, because there’s this way of joining these genres, playwriting and the novel — if they were every really separate. But the idea is clearly from this one specific spot in The Tin Drum, which I’ve never even reread.

LM: Did you always know that the climactic scene in The Yid, when Levinson and company attempt to kill Stalin, was going to be both scripted in the plot and written out as a script?

PG: Well, you never know what you know. I always saw this novel as a circus act: Here’s this lunatic — me — on a tightrope, walking across, and the audience is looking up and thinking, When is this idiot going to fall down and break his neck? That’s the whole thing. I knew if I fell and broke my neck, I wouldn’t get to the ending.

When I did get to the ending, the only way I could come up with to do it was to write a play within a play. I had to find a way to not make it distasteful, because you’re talking about regicide, really. Do they commit regicide? Do they fail? Do they commit it and get killed, or rescued? Do they live or do they die? That wasn’t really worked out for me.

But it was also interesting how Shakespeare fits into this thing. I understood from the beginning that I wanted to play with the idea of blood libel. I wanted to claim it in the biggest possible way — which is totally Shakespeare!

LM: Except that you used Lear, not The Merchant of Venice.

PG: I couldn’t get to The Merchant of Venice. It’s interesting that the Moscow Yiddish Theater never staged it, but it was more interesting to consider a play that they had in their plans and never staged because the war got in the way, and that was Richard III. Can you imagine a more anti-Stalinist play than Richard III? It should have been banned!

LM: I imagine it would be intimidating to write Stalin, especially this particular demented, hallucinating Stalin. How did you work up to that?

…I needed the character of Stalin to be strong. He could not be a wimpy Stalin

PG: It was the biggest challenge of this whole book, figuring out how to stage Stalin. Since I put myself into the play format, or at least this book-like-a-play format with the landmarks and metrics of a play, I needed the character of Stalin to be strong. He could not be a wimpy Stalin. I didn’t want to make him up, but I did have the freedom to make him a hallucinating Stalin — which he was! He was whacked out! You’re talking about an old guy who hates Jews, hates doctors, conflates Jews with doctors — which he would have done. I mean, old guys not liking doctors is not unusual. But usually they don’t kill doctors; they sue doctors.

LM: Or just avoid them.

PG: Sometimes they kill doctors, I guess, but it’s rare. So here’s what happened: I had to find ways of figuring out what dementia would accentuate in Stalin, and I found two places that were extraordinarily helpful to me. One was a line out of his daughter Svetlana’s memoir, Twenty Letters to a Friend, where she says, “Stalin, towards the end of his life, displayed photographs cut out of Soviet magazines that depicted the happy childhood of Soviet children.”

So you’d have Young Pioneers running around, playing with model airplanes, doing all those things that I actually did as a Young Pioneer. That was interesting, because here are these children who aren’t real, but are playing some role in Stalin’s mind. She never understood what it was. I really don’t like her explanation, which was that these were substitutes for the grandchildren that he had no relationship with. That’s too Svetlana-centric. I kept the children, but I didn’t keep her explanation.

LM: It’s actually a heartbreaking detail, and her explanation makes it less heartbreaking.

PG: Right. It’s heartbreaking, but it opens up demonic potential. It unlocks it! I was looking for demonic potential. I needed to get into his skull. So that’s where I got Stalin’s visions. The happy children in the illustrations on his walls come alive with the help of his dementia.

LM: So what’s the second place?

PG: Conversations with Stalin by Milovan Djilas, which I think is the best memoir about Stalin. A lot of Djilas’ Stalin is in The Yid. Djilas met Stalin three times, and all three times were important for me, especially the first.

Here’s the story: Djilas comes into the Kremlin at the end of the war, and he has a delicate question for Stalin. The Soviet army’s in Belgrade, and it turns out that Soviet soldiers are raping and murdering Yugoslav women, which is not really conducive to good Soviet-Yugoslav relations. And Comrade Stalin thinks the question is absurd. He explains, “Imagine, a soldier marches across Europe, losing his friends, and now he wants to have a little fun with a woman. Who’s to say no?” The next night at a banquet, Stalin comes up to Djilas’ wife. He kisses her on the mouth, and then he says to Djilas, “You’re not going to claim rape, are you?”

It’s an evil spark, but it’s a spark.

So there’s a lovely description of this diabolical, taunting guy. He plays with his kill. He has no ability to feel compassion, but he can have fun. It’s an evil spark, but it’s a spark. He’s not an automaton. He is someone who taunts.

LM: All right, so that’s how you wrote your villain. How did you write your hero, Levinson?

PG: Levinson is completely made up. The point of contact with him was my apartment in Moscow. When they come to arrest him, he’s in my apartment, so I could imagine it that way. The other point of contact is a Soviet novella about the Red partisans fighting alongside the Trans-Siberian Railroad in the Urals. The commander in that book is called Levinson. His first name and patronymic are different, but here’s this Levinson who’s obviously Jewish, a Civil War commander, who’s somehow important. For me it was huge to come up with my own Levinson who was similar to that Levinson, but not completely the same. I didn’t want them to be twins. It would have been too much. As a shortcut for myself, he’s that Levinson, but my Levinson becomes a dark clown. And I didn’t make that up! After World War One the dark clown was huge in Russia. It’s a way of expressing pain, but my Levinson isn’t expressing pain. His objective is to prevail by force.

LM: He’s kind of superheroic.

…the only question left is whether I, the author, will fall off my tightrope and break my neck. That’s the element of jeopardy. I’m the dark clown here.

PG: He’s out of touch with reality! You look at him and think, Only a man who’s out of touch with reality would do the crazy stuff he’s trying to do, and then you think, Well, maybe he’ll succeed. And then the only question left is whether I, the author, will fall off my tightrope and break my neck. That’s the element of jeopardy. I’m the dark clown here.

LM: But you do have help, because Levinson has a team. He’s not trying to kill Stalin alone. He has co-conspirators.

PG: I made his co-conspirators up. Well, one, Rabinovich, is my grandfather. He was the head of Drugstore No. 12 near where I lived, but I wrote my whole family out of that apartment. So he’s real, but I made him up, too. And then Kima would have been a relative, had she existed. Her father was a made-up first cousin of my grandfather’s. He’s Rabinovich’s cousin, I mean. I made good use of my family.

LM: Could you talk to me about why you did that?

PG: I needed to find ways to relate. My own geography helped. The Moscow of the 1960s and early 1970s isn’t going to look different from the Moscow of 1953, so I knew it — that Moscow that doesn’t exist. That Moscow is dark, snowy, cobblestones and communal flats. So I used that.

And then there’s Shmuel Halkin, the man who translated King Lear into Yiddish. He’s in the novel, but in real life he lived across the street from the dacha where we lived when I was born, and my father brought me across the street to meet him. I can’t possibly claim to have any memory of this, but the idea of there being that kind of intersection on this earth is very interesting to me. I met the man who wrote Kinig Lir, technically. Just because I don’t have any memory of it doesn’t make it any less real, and so it shows how small the world is. That’s what the book’s about, really: The smallness of the world and the polarity of fascism and non-fascism.

I accepted the fact that in 1944 a Jewish woman was arrested for killing somebody, but the blood libel was hard to accept.

Then there’s this one case from which this book really stems. When I was ten, my friend Alyosha and his father and I were walking down the street, and his father pointed to the entryway of an apartment building and said, “See, over there is where in 1944 they arrested this Jewish woman. I saw her being led away for having bled a Russian girl into matzos.” And I was kind of shaken by that story. I later came back to the same gentleman and said, “Can you really tell me that you actually saw this?” And he said yes! He described it in detail, this poor woman being led away during the day, the invalids sitting on the benches with their canes and their crutches, saying, “We fought for the motherland and the Jews are bleeding our children!” To me this was an incredible story. I accepted the fact that in 1944 a Jewish woman was arrested for killing somebody, but the blood libel was hard to accept.

LM: Was there a point when you did believe in the blood libel?

PG: Yes. It would have been about eight minutes, longer if my parents weren’t home. But my mother was a teacher and this happened after school, so it was probably the eight minutes that it took to walk from my friend’s apartment to mine, and then my mother explained it. I came back to school the next day and said, “Your father’s crazy.” But I asked him many years later and he came back with the same story.

The other piece that is really interesting about this is, I was reviewing a book for The New York Times by Yakov Rapoport, who was one of the supposed doctor-murderers imprisoned at the time. His daughter told the story she heard, which was that the Jew-doctor from her apartment complex was arrested for taking pus from cancer sufferers and injecting it into people on buses.

LM: Which went straight into The Yid.

PG: Straight into the book. If I had a legend to put in there, I did. Another amazing resource for me was a novella called This Is Moscow Speaking. That’s a terrible translation. It’s the beginning of a radio broadcast: “This is the voice of Moscow. This is Moscow speaking.” The story’s set in the ’50s; this group of friends is hanging around at the dacha, playing volleyball, swimming in the river, and then they hear the radio saying, “This is Moscow speaking,” and the announcer is saying that society has reached a point where it would be possible to hold a day of open murders. You could ‘deaden’ whomever you like, as long as they aren’t government officials in uniform or employees of the transportation system. And then the author describes the day of open murders. He went to prison for this. It’s an absolutely beautiful story, but what it really tells you is that there’s this stratum of the intelligentsia that’s thinking about what this pogrom would have been like. There’s a Jewish character who says, “This is all about the Jews. This is how they’re going to kill the Jews.” That’s an important piece of my book.

LM: It sounds like your writing process was a lot of putting pieces together.

PG: It was. After the leap of fiction, but it was. Actually, the hardest part of the process for me was squeezing out my inner Bulgakov. I was really worried about sounding like Bulgakov. I hope I don’t.

LM: Was there anyone you did want to sound like?

PG: I wanted to sound like no one else. There are a lot of contemporary writers I deliberately did not read because I didn’t want to be in a dialogue with them. I’m looking forward to reading that body of work now, but I didn’t want to be in dialogue. I had no problems reading Singer or Malamud, or Vasily Grossman, who I just love. But how do you write like Vasily Grossman? You don’t.

And Malamud — you can get into a dialogue with Malamud, but his characters are so different. My characters, all of them are intelligentsia, so a simple man, a Jewish worker, just isn’t my character. Mine are all going to be yelling at each other, arguing about obscure points, getting into all kinds of radical, aggressive movements. I mean, imagine Seder at my house, or your house. There are four conversations at once, on eight different topics — I don’t know how they do it, but they do it.

LM: And somehow everyone is arguing between the conversations.

PG: They’re arguing, but there’s no focus! Elijah is the focus, the poor bastard.

LM: I was scared of him when I was a kid.

PG: Oh, everybody was. Well, not me, because when I was a kid we lived in a communal flat with some people who were probably informers, and my grandfather was a Party member, so the last thing he wanted to be seen doing was having a Seder. So my grandmother celebrated the Day of Victory over the Nazis, which was Seder-worthy, with gefilte fish and things like that. It was a secret Seder.

LM: Some real Soviet syncretism there.

PG: It seemed normal. Anything can seem normal.

LM: Not the things in The Yid! A human killing another human with a bite cannot be normal.

PG: No. I made that up. That’s not normal. The idea of bringing someone down as prey — I don’t know if anyone’s done that before. I called some surgeon friends and asked if it was possible. Fortunately, I have enough friends who understand injury, so I said to them, “I really want to do it this way. I’m claiming blood libel, so I might as well have a flying Jew bite through someone’s jugular.” I mean, I’m probably claiming the whole anti-Semitic mythology. I am. Why not?