interviews

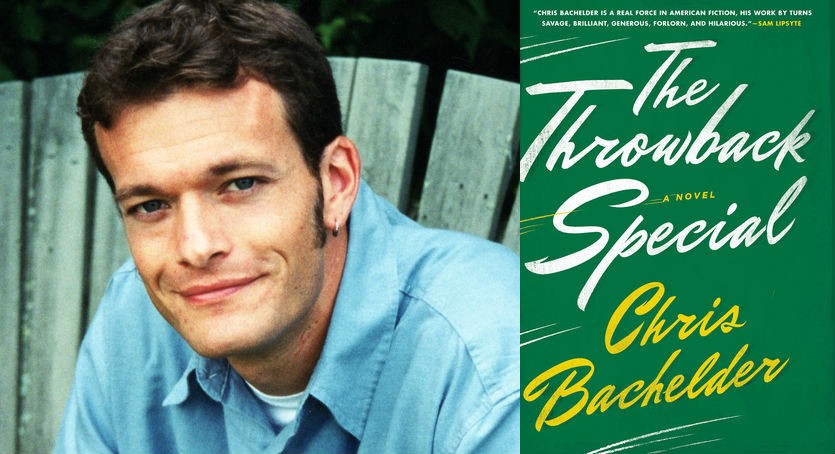

Chris Bachelder, Author of The Throwback Special, Writes the American Male Psyche

I first encountered Chris Bachelder’s novel The Throwback Special in The Paris Review, where he serialized it starting last spring. I missed the first installment, and so I began the second one cranky. I’m not going to get this, I thought. And it’s about football anyway. I don’t care. And yet I read, and kept reading. I got hooked.

Of course The Throwback Special isn’t about football, which I should have seen coming, Friday Night Lights fan that I am. It’s about a group of twenty-two middle-aged men who convene in a hotel every year to re-enact the play in which Lawrence Taylor broke Joe Theismann’s leg, which is to say that it’s about community and nostalgia, violence and anxiety. It’s about masculinity, bigtime. Football is just an excuse. Let’s start there.

Lily Meyer: I’d like to talk about my own interest in your book. I do not watch football, I’ve never watched football, I’m young and female, and I loved The Throwback Special right away. I was surprised, and that made me curious: are you surprised, too? Who did you imagine reading The Throwback Special as you were writing it?

Chris Bachelder: That’s really gratifying, because I tended to think of it as a very small audience. With my last book, I had trouble placing it at first. So with this book, I really stopped thinking about audience in a pretty liberating and great way. So now that we’re here and there’s interest from people I didn’t think would be interested — it’s wonderful, and yeah, it’s surprising.

LM: Do you think of yourself as being an experimental writer? And if so, did you always?

CB: On the one hand, any good novel of any stripe is going to be experimental in its way, so it’s such a hard word. Any novel that’s interesting is going to try something new. When I started, though, I definitely wore that jersey. I wanted to be on the experimental literature team. And I think what’s happened is I’ve gotten less interested in formal experimentation, and more interested in a subtler kind.

Flannery O’Connor said, “If it looks funny on the page, I won’t read it.” There was a long time for me where if it didn’t look funny on the page I didn’t want to read it, but I’ve expanded my own tastes. I think there are experimental aspects of The Throwback Special, but it’s not as ostentatious, formally.

LM: I mean, the writer it reminded me of the most was John Le Carré.

CB: Really?

LM: At least in the humor it did. I think your jokes are in the same register — and I love Le Carré’s jokes. I wanted to ask about that, actually. Did you set out to make The Throwback Special funny?

CB: I see myself predominantly as a comic writer. If there’s no way to come at an idea from a comic stance, I lose interest pretty quickly. But I hope my idea of humor has expanded, become more complex and nuanced, started to intertwine with other emotions. I don’t want my work to be intermittently comic, but comic at the same time as other things. Comic and melancholy, angry. I’m looking for a good tonal mix.

LM: What would you say are the driving emotions of The Throwback Special?

CB: If nostalgia is an emotion — well, it’s a state, but it’s certainly a nostalgic book. There’s a sense of melancholy. And I don’t think bewilderment is an emotion, but these men strike me as slightly bewildered.

LM: They seem bewildered to me. They seem anxious to me, too.

CB: [laughing] Oh yeah, yeah.

LM: Really, really anxious.

It’s emotionally complicated, and as a writer, you don’t have to sort emotional complication out. You just enter it.

CB: I would hope that — talking about guiding emotions, I think what attracted me to the Theismann play is that it’s a complicated weather system in that it’s brutal. It’s savage. That’s a kind of cold front, but when you add time and nostalgia, you bring a warm front of wistfulness, a kind of ache. It’s emotionally complicated, and as a writer, you don’t have to sort emotional complication out. You just enter it.

LM: That’s something I love about The Throwback Special — there’s no sorting.

CB: I’ve just ceased to think that’s my job as a novelist. I don’t sort anything out. Besides, I don’t think the men quite know why they re-enact this play. I didn’t know myself until I started doing this kind of interview.

LM: So now you know?

CB: Well, one interesting thing I’ve found is that the men think the purpose of the weekend is the play, but the purpose is something else. They only vaguely understand what it gives them. And that was true for me. When I showed up in front of the computer writing them, I thought I was coming to do something with the play. I had to be fooled just like the men into doing what I was really doing, which was writing about belonging.

Nostalgia is about belonging.

I mean, it’s complicated why the men show up. They aren’t even friends, but they’re getting a kind of intimacy without friendship. And they’re having a weekend that’s completely different from their normal lives. That gives them a sense of cohesion and group membership and, yeah, belonging.

LM: How do they know each other? Do you know?

CB: No, I don’t. I didn’t want to get into how the men know each other, or setting up the ritual of the play. When you do a weird premise like this, you kind of just want to draw a circle around it and keep readers from asking too many questions.

LM: I reacted really strongly to the play itself, which is narrated not by the men but by spectators in the stands. My initial reaction was, “No! This is so unfair! I want to be on the field with them!”

CB: That was a risk. I had written an earlier draft where I tried to dramatize the play from, but it just didn’t feel convincing. I had to come at it a different way, with some distance.

LM: I just don’t know how you could possibly have made watching the play from within better than watching it from without.

CB: It was like if you’ve ever tried to write a fight scene. It felt too overwritten, too melodramatic.

LM: You lose the emotions in the play-by-play.

CB: Right. Also, the Theismann play takes five seconds. It’s hard to describe it in a way that honors its quickness.

LM: That’s what made me realize the narrative had to go outside the men. From within, it would have gone on too long. From the stands, you get the, “Oh my God, it’s over?”

CB: Yeah, the, “What just happened?”

LM: And the entire book has been building to the play! It’s such a sad moment. It seems like this is the highlight of these men’s years, and then it’s over so fast, it’s really sad!

CB: That’s gratifying to hear, that a reader felt that way. The elevator pitch of this book makes it sound absurd, farcical, maybe zany, but my job is to try to make readers care a bit about this premise, to take the men seriously. So definitely I was aiming for a kind of gravity and sadness to the whole thing, but especially to the end.

LM: So what was the very first bit of the premise?

CB: I saw the play when I was fourteen, so it’s always been in my head. It never leaves your head. I started thinking about it again, and feeling something literary there, some energy or power, so I started watching the play again. I’m kind of squeamish, so I watched it from across the room with my hands over my face.

I was wrong when I thought the power was in the play itself.

I was wrong when I thought the power was in the play itself. It was only when I understood that the power was in the play plus twenty-five years, plus thirty years, that I knew that the play was not my subject. What happened, if I had to guess, was that I watched the replay so many times that the players started to seem like actors. You watch something happen twenty times and you start thinking, “Wow, they are all moving perfectly together to make this catastrophic event happen.” But it was like I had to trick myself. I would never sit down and say, “I am going to write something about the American male psyche.”

LM: So how many drafts did you go through before you understood that you were writing about the American male psyche, not the Theismann play.

CB: Well, my process is to mull and think and despair and really just work a premise over, trusting that there’s something there, and then what I’ll do is I’ll think, I maybe can solve this puzzle of point of view, stance, tone, style — it’s like a Rubik’s cube. I’ll start and get not very far in before I know there’s something wrong. I’m not writing with conviction or energy. So I wrote a series of false starts. I wrote it as a short story, and thought, “Well, this didn’t work at thirty pages, so maybe I’ll try it at two hundred,” which is kind of perverse.

LM: I know you wanted to write about this particular play, but it’s a complicated thing to write about the Washington Redskins. The first two words of the book are “Washington Redskins.” At one point Derek, one of the men, thinks, “Good lord, they were named the Redskins,” but it’s the only time you explicitly address the fact that this team just has a racist name. What was your thought process about that?

CB: I’m not trying to give myself a free pass, first of all. But because it’s such a nostalgic book, and because that controversy is relatively recent, it wouldn’t be in the men’s consciousness to object to it. Again, not giving myself a pass, and not giving the men a pass. It’s an offensive name. I, like so many people, wish they would change it.

LM: I grew up in D.C. and I live in D.C. now, and everyone I know just calls them “the sports team” or “the football team” — we don’t use the name. But you couldn’t do that.

CB: It’s a tricky issue, but to draw attention to it would have drawn attention away from the central drama of the book. But that passage with Derek was at least a chance to bring it into one of the character’s consciousness.

LM: Honestly, the fact that no one but Derek ever comments on the team’s being named the Redskins drew my attention to the fact that these men are from not just a different generation from me, but a different era.

CB: These guys are interested in the perfection of a play. The re-enacting impulse is an impulse toward perfection. They’re completely committed to everything that was the case in 1985, including the name.

LM: Did you do research on re-enactors, or interview any other kinds of re-enactors?

CB: My research was pretty limited to the play itself — watching it, and then reading about it. I didn’t research re-enactors in general. One character in particular doesn’t like that term. He doesn’t want to be associated with Civil War re-enactors, even though I think the impulse is similar.

…if the Theismann play means anything, it means we’re not in control, even though we think we are.

What’s interesting is that if the Theismann play means anything, it means we’re not in control, even though we think we are. The football players go to the line of scrimmage and everything goes wrong. This play represents the really dark underside of what can happen, and is a lesson that we’re not fully in control, and so the paradox of the book is that if this is what this play means — utter contingency and chaos governing our lives — what do the men want to do? Re-enact it perfectly. Control it.

LM: How much emotional distance did you have from the men as you were writing?

CB: The omniscient point of view — roaming, mobile, but capable of going way deep — requires both intense proximity and dispassionate observation. I really like that point of view as a reader. I was committed to them, immersed in them, fascinated by them, but then I had a certain distance and detachment.

I’ll say that I never for a minute thought that the men are ridiculous. Of course, I have some that do or say ridiculous things, but I hope I’m not making fun of them. Did you think the book was satire?

LM: No. Absolutely not.

CB: People have called it that, and I don’t get to say what the book is, but I didn’t set out to write a Satirical Book About Men. That would be a bit unsporting, to invent an absurd premise and then pile on about how ridiculous they are. So I felt some tenderness toward the men and their troubles.

LM: How much did you develop the men as individuals in your head?

CB: Well, I had a list to keep track of who had two kids, how they looked, details like that. But at some point I realized I wasn’t going to develop twenty-two people. A reader could never keep up with twenty-two people. Better for a reader to let it wash over her.

LM: So what was the point of Adam, who comes late and leaves early, unnoticed?

CB: As I wrote the book I was really troubled by the lack of event, the lack of suspense or tension, but when I added too much, it was too much conflict. It took over the book when I added a big piece of outside plot, and so I wasn’t able to just watch them talk. So instead I tried to add tiny things throughout, little things to irritate them.

As you say, Adam is missing at the start, but they don’t even notice he’s missing. The book perversely fails to make a plot point where it could have. They never realize he was gone. That was a way to suggest that the ritual is coming to a close, or that it’s wearing out. Adam’s mysterious late appearance and mysterious early departure was a way to show decay and introduce instability, but not a radical instability that takes over the book.

LM: The one other character I want to talk about is Fat Michael [who plays Theismann and who is in perfect physical shape]. How did you develop him, and how did you decide he would be this year’s Theismann?

CB: I was just playing with the idea that there would be two characters with the same name, like, okay, there will be two Michaels, so let’s develop a nickname in that masculine style that’s part tribute, part criticism. They could call him Fat Michael if he were really fat, but that would be cruel, so instead they call him Fat Michael because he’s in great shape.

…when we write, what we have to do is think about what our characters want and not give it to them.

And then the lottery where the men choose which player to be — that was fun to play with. At first I tried to do a truly random lottery, but I gave that up. I wanted to be in control. You know, there’s a psychological burden to being some of these players. They don’t break the Theismann’s leg every year, it’s ceremonial, but there’s still a burden to playing Theismann. And when we write, what we have to do is think about what our characters want and not give it to them. Fat Michael is someone who’s committed to his body, to maintaining his fitness as he gets older, and so he’s someone who wouldn’t want to even ceremonially or metaphorically get struck down. It gets to him.

LM: Did you ever think about having there be a ceremonial injury, either intentional or unintentional?

CB: When I began the book, it was unclear in my mind whether they would break Fat Michael’s leg. But it was like the jazz motto, “Think of a note but don’t play it.” I was thinking about outrageous violence but wanted to steer away from it. What seemed more in line with the book was the injuries of middle-aged men — you know, some of them pull a muscle. That’s all that happens to them.