interviews

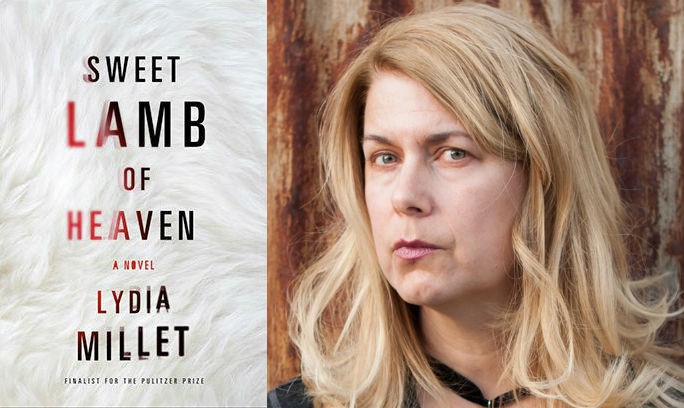

Lydia Millet on Good, Evil and the Future of the Literary Thriller

I have a new mission in life: I’m going to make Lydia Millet famous. Honestly, she should be literary-rock-star level already. She’s an exceptionally funny writer, but her sense of humor is nothing compared to her capacity for empathy. Her books glow with it. And none more than her new novel, Sweet Lamb of Heaven, in which a smart, sensible, sane woman named Anna hears the voice of God emanating from her newborn daughter. That’s not a spoiler; it’s the first page of the book. What I will not spoil for you is Anna’s flight from her evil political-candidate husband, which is the engine of the book’s plot — a plot which is thriller-level gripping, but I don’t think Sweet Lamb of Heaven is a thriller. It’s an exploration of good and evil, of language, and of motherhood; it’s high literary fiction; and, you know, it has some demons. What more could you want?

Lily Meyer: Here’s the thing about Sweet Lamb of Heaven: I’ve been talking about it to everyone I know, but I haven’t described it in the same way twice. So I really want to know how you describe it.

Lydia Millet: I suppose in basic terms it’s a story about a woman whose child is threatened, whose mental privacy is threatened and, finally, whose life is threatened. There are some supernatural elements — you know, actually, I was just looking up statistics about how many Americans believe in the supernatural, and they’re amazing. Something like 77 percent of Americans believe in angels, and — dig this — among people 18 to 29 years old who are not affiliated with any particular religion, something like 63 percent believe in demons and 85 percent believe in the supernatural.

Meyer: That is wild. Did you know about this when you started writing Sweet Lamb of Heaven?

Millet: I had no idea. I just wanted to write about language and ideas about God, and I wanted to do it in the context of a story that had suspense and tension and darkness and intrigue. And I sort of have a weakness for movies like “Fallen” or “The Ring” where there’s this real clear good-and-evil dichotomy, and I like it when evil is vested in a child. So I liked that structure, but I had no idea that there was any kind of realism associated with this book, except on the political end of the spectrum, depending on whether you interpret the antagonist as a demon or not. I thought the idea that he was a demon was outlandish — and I wanted it to be outlandish!

Meyer: How do you think your novel interacts with Christianity? I know there are a couple moments of specific Christian imagery, but I found myself thinking, from my secular Jewish perspective, that this book is sort of about the Christian God, but it doesn’t feel Christian at all.

There’s every reason Christ shouldn’t belong to the rich and powerful, but right now he does in this country.

Millet: I think the book wants to make an argument toward a broader understanding of God that is non-sectarian and is not the birthright of people, and certainly not of any specific monotheism, but is understood to be the birthright of all sentient creatures. And the plot intersects with this strain of fundamentalist Christianity that I believe has been co-opted by the corporate right and used by the corporate right to claim the moral high ground, when of course there’s no reason that Christ should belong to the rich and powerful. There’s every reason Christ shouldn’t belong to the rich and powerful, but right now he does in this country. It’s partially a book about that, but it’s not a Christian book — though I don’t want to dismiss any form of religious faith. Going forward, I think there’s a crucial role for faith to play in politics, especially in things like climate change. So I didn’t want to disrespect faith at all in this book. I wanted to look at the ways faith is exploited.

Meyer: There’s not that much political fiction getting written now, I think. Are there novelists you think are doing it particularly well?

Millet: Not directly political fiction, no. Some humorists have worked pretty well with shadow politics and symbols — like Chris Bachelder. I thought The Throwback Special is really good allegorical fiction. And then of course George Saunders and Donald Antrim, but they’re not directly political. I would like to see more literary political fiction.

Meyer: Me too! I was thinking as I read Sweet Lamb of Heaven, When’s the last time I read a novel this explicitly pro-choice? And I don’t know!

Millet: There’s a real reticence in literary fiction to be overtly political. You don’t want to be seen as advocating; you want to pretend to some aesthetic objectivity. I understand that partly, but I think it’s a cop-out sometimes. When things are difficult is really when you should probably take them on.

Meyer: To go back to the question of how you describe the book, do you think of Sweet Lamb of Heaven as a thriller?

Millet: Some people have called it that, and I think it can be framed that way. It has a certain formal kinship with thrillers, but I saw it as more of a form of horror. Maybe it’s a supernatural thriller, though people have called it a psychological thriller, and of course it is psychological, in a way.

Meyer: Well, that’s what literary fiction is, right? But your publicist pitched it to me as a psychological thriller, and, I mean, once she’d mentioned your name she could have pitched it to me as whale song and I would have been like, Great, send it to me, but that description did not prepare me at all for the extent to which Sweet Lamb of Heaven is a meditation on language.

Millet: That was where the book started, with this idea that I have about deep language. That was what got me writing.

Meyer: I’m so curious about how you actually write the sentences in a book that you’ve decided will be about language.

Millet: I wanted the diction in this book to be pretty straight. I wanted a reliable narrator, and really, my bailiwick in the past has been the flawed narrator. But here, because I had these outlandish conceits, I needed someone authoritative. She’s arch, she’s intelligent, but she’s pretty straight, and I needed that foil to play against ideas about the divine and the supernatural. You can’t really have a narrator who seems overtly untrustworthy, which is the kind of narrator that’s easier for me. But I wanted to have her be believable. I didn’t want the reader wondering whether she was just a kook. It wouldn’t have served my ideological or narrative purposes, and I think it’s sort of boring. I’m a little jaded about the Am I crazy thing that you see in a lot of horror movies. I tried to dispense with that, to say, This isn’t a story about unreliability.

Meyer: I think what ended up happening was that you created an assertive and direct female narrator of a kind that I have not seen often. That was one of the most fun things about reading Sweet Lamb of Heaven for me. I kept thinking, Oh my God, this woman is telling me that she knows she’s right! This never happens in fiction!

Millet: Obviously it’s crucial to the story that she’s a woman. And I like writing from an alleged male perspective too, but this novel had to have a strong female voice that wasn’t a victim voice.

Meyer: To what extent do you think of this as a book about motherhood?

…the greatest harm that can be done to you is to your child. You’re just a second-class citizen in your own life.

Millet: It is partly about that. You become so vulnerable as a parent, and I didn’t really anticipate that — the degree to which you are vulnerable for the rest of your life once you have children. You can always be gotten to through your children; the greatest harm that can be done to you is to your child. You’re just a second-class citizen in your own life. The stakes are very high, obviously, and that makes a mother a very raw kind of target for anyone who is willing to mess with the child. It’s about motherhood in that sense: Anna’s protectiveness and her focus on her child.

Meyer: It’s so different from other books I’ve read about motherhood recently. I’m thinking mostly of Dept. of Speculation, which I love.

Millet: You know that’s by my best friend, Jenny Offill.

Meyer: I had no idea you were friends!

Millet: She was the first person I told about Sweet Lamb of Heaven. I remember I said to her, “Jenny, I have the worst idea for a book. The single worst idea for a book I’ve ever had. There’s this baby, and God speaks through it.” And she was like, “You should do it!” She’s been a champion of the book from the beginning. Anyway, I thought the way she wrote about motherhood was very delicate and nuanced and excellent.

Meyer: Do you find that there are questions you get asked, as a writer, because you are female?

…“You’re a mother. How do you find time to write?” How many fathers get asked that?

Millet: I think the entire playing field is different for interviews when you’re a woman. You tend to get more personal questions, more challenging questions — not in the sense of difficult, but there’s less respect. There’s less talk of genius and brilliance. Instead, there’s stuff like, “You’re a mother. How do you find time to write?” How many fathers get asked that?

Meyer: That was the question I had in mind, actually. I hear female writers getting asked that all the time and it makes the hair stand up on my neck. I think the question should be, How do you protect your brain space for writing from your day job and from your life as a human, as opposed to your life as a writer?

Millet: That is a better question. And the answer for me is that I protect it by not teaching. I like students, but I don’t like reading a lot of manuscripts by students. I get infected by them. So it’s good that I don’t teach very often.

Meyer: Do you have a fantasy book that you’d like to write? Not genre-fantasy — I mean your dream book.

Millet: I would like to write a book that felt urgent. When I was writing My Happy Life I felt really urgent about it, and it actually changed the way I thought about people, writing that book. The way I thought about books, also. I was a colder writer before that book. I’d like to write another book that changed me. It was interesting to see that that could occur, that something you created could change the quality of your emotional life.

Meyer: And, finally, do you have a fantasy reader? If you saw someone on the subway reading your book, who would you want that person to be?

Millet: It should be someone who hadn’t read any of my books before and wasn’t inclined toward books of the sort that I write. Someone who came to it accidentally and liked it, who stumbled on it, but for whom it was not a typical pick. Someone for whom it was strange. That’s who my fantasy reader would be.