Interviews

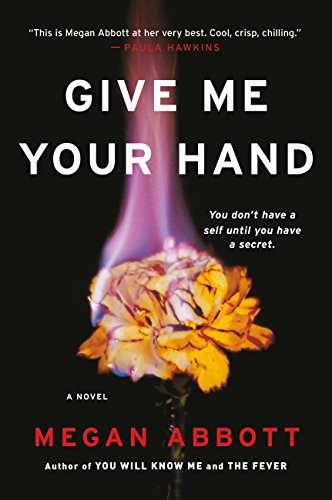

Megan Abbott Tackles Deadly Misogyny in the World of Science

The author of ‘Give Me Your Hand’ on the biology of female rage and the consequences of bottle rage

Crime writer Megan Abbott has never met a closed-up world she didn’t like. From cheerleading and gymnastics in Dare Me and You Will Know Me to the noir nightclub settings of Queenpin and The Song Is You, Abbott is fascinated by the drawn curtain, the locker room, the space only a chosen few can enter.

In her ninth novel, Give Me Your Hand, that space is even more competitive and cutthroat than usual. The action takes place in the Severin Lab, among a group of post-doc biologists jockeying for two coveted spots studying premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or PMDD, which causes uncontrollable, agonizing mood swings. Kit, the only woman in the lab, is praying that this will be her moment — and then Diane, her former best friend, appears in the lab, bearing a Harvard degree, a reputation for brilliance, and a secret that only Kit knows.

I spoke to Megan Abbott on the phone about female rage, misogyny in the world of science, and what can happen when you bottle up anger — or keep a secret — too long.

Lily Meyer: Why did you use biology as your entry point for a novel about female rage when biology is so often how women’s anger is dismissed?

Megan Abbott: I never intended to write a book about female rage. I didn’t even know Give Me Your Hand would be about science. I wanted to write about the notion of passing on a secret that burdens its recipient. I was haunted by the notion of a secret as albatross. Beyond that, I knew that when the secret-teller and secret-carrier came together later in life, it should be in a competitive work environment. I’d written many books about sports, so I wanted to make it a competition of the mind. After that, I became interested in women in the sciences, and how hard it was for them: how many are pushed out by institutional sexism, by open misogyny, by operating in an all-male environment for so long.

LM: So often, male characters in this book dismiss Kit, the protagonist, by saying she works hard, not that she’s smart. They call her a worker bee. How have you seen this form of sexism operate in the world?

MA: I was talking about this with a male friend a couple months ago. He said, “If someone told me I worked hard, I’d take it as a compliment,” and I said, “If someone said that to you, it would mean something completely different!” It’s so loaded. The way women’s work is diminished is that it’s not about the quality of the work, or our capacity or intelligence. We just grind harder — that feisty little one, you know? Again, I wasn’t thinking consciously about this when I was writing the book. It came up bit by bit, in scenes. Then the presidential campaign started, and stakes felt higher and higher. I became hyper-aware of the ways women have to put sexism aside and trudge forward until we can’t any longer.

The way women’s work is diminished is that it’s not about the quality of the work, or our capacity or intelligence. We just grind harder — that feisty little one, you know? I became hyper-aware of the ways women have to put sexism aside and trudge forward until we can’t any longer.

LM: As a pair, Kit and Diane move forward in such different ways. Kit has her head down; Diane has her head in the clouds, though not in a happy way.

MA: I was interested in exploring a character who grew up with trauma, and who doesn’t quite connect to the world or the self in the same way others do. Diane is smart enough to know she lacks that connection, so she performs it. That struck me as very painful. Kit’s more like the rest of us: she puts her feelings on a shelf at the top of a closet. It’s the way so many women operate.

LM: Speaking of performance, why is there so much Shakespeare in this science novel?

MA: The real-life inspiration was a girl who confessed a crime to another girl because they were reading Hamlet. The idea of literature inspiring a confession was irresistible. Once I had that idea in my head, I started thinking about how female power works in Shakespeare. The title comes from Lady Macbeth, and during the campaign, Hillary Clinton was always called a Lady Macbeth figure. I still bristle every time someone uses that term, because first, I think it’s sexist, and second, it’s a wrong reading of that play!

LM: If you had to pick one, which Shakespeare character would Diane be?

MA: That’s hard, because you never tap Diane’s center. I might choose someone like Iago, who doesn’t understand why he’s doing what he’s doing. That’s why we’re all fascinated by Iago. Also, Iago always seems like he’s in some ways a projection of Othello’s, and I often thought that Diane was a projection of Kit’s. She does what Kit is afraid to do. Kit would like to be able to operate like Diane: to not care, to not connect with all the feelings that she’s burdened with.

Megan Abbott on Family, Ambition and the Mystery of Gymnastics

LM: Is there a moment when Kit truly acts on her anger? How would that look for her?

MA: She has no idea, which I think is true for a lot of us. One of the things that’s been so striking for me in the last two years is the way anger gets sublimated into other places. It never dissipates, just bubbles up where it’s not expected. I think a lot of women feel that to fully release their anger would be too dangerous. That’s why Kit, like Diane, isn’t capable of having a romantic relationship. Feelings are dangerous.

LM: As a result, there’s something alluring in the novel about Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder, about the inability to control one’s rage. How did you find PMDD?

MA: I wanted to use a women’s health issue. I had heard of PMDD, but I had no idea how common it was. It’s so under-reported, and denied so often. There’s a lot of stigma and shame. Doctors steer women away from believing they have PMDD, which is a classic example of the way women have been treated by the medical industry. But once I started reading, I couldn’t tear myself away from the case studies. Imagine a situation where your body takes over your life for a week every month, and your emotions are completely uncontrollable. That feels very powerful — disruptive, painful, but there’s definitely a power in it. It’s so unacceptable for women to behave that way.

LM: Now that the book has been out for a bit, what responses have you gotten from women in science? And women with PMDD?

MA: It’s mostly been women in science. I thought I’d hear more from women with PMDD, but there have only been a handful — though I’ve learned that several women I know have it. There’s still a great stigma attached to it, and I was very conscious and wary of how I used it, because to explain how it functions would be to spoil the end of the book. I did have to explain to one person that the book does not claim PMDD makes you a killer. The book claims the opposite, really.

I was interested in how hard it is for women in the sciences: how many are pushed out by institutional sexism, by open misogyny, by operating in an all-male environment for so long.

LM: Give Me Your Hand feels mythic, somehow. Why is that?

MA: I wanted it to feel gothic, out of time, slightly eternal. Once you do that, there’s such freedom. You can go darker and stranger. When you’re writing a crime novel, the logistics can be so frustrating, especially with phones, technology, and social media. It’s so great not to have to tangle with that.

LM: Does writing in a mythic register also make it easier to think about the book’s big questions of morality?

MA: Absolutely. That’s why I so often write books set in hothouses. Environments like that create their own morality, which I think is so interesting, especially when that morality clashes with one of the characters. It’s the bubble effect. Or a better way to put it is to say there’s a moral drift that occurs, for all of us, when we’re in closed environment. That drift fascinates and horrifies me. For instance, I read so much about labotage — lab sabotage. How people commit it, and respond to it, fascinates me. What happens to you in that kind of situation, where you’re slowly distorted by the world around you?

LM: Outside the lab, what do you think Kit’s feminism would look like?

MA: I always thought that Kit’s main issue in the larger world was class. Because she’s always been the only woman, she doesn’t think about gender quite the same way. Class becomes a larger divide, or one that she carries more. She views everyone through a class lens: those shoes are expensive, that shirt is expensive. It kept coming up with Diane, because in some ways, the combination of Diane’s brilliance and her not having to worry about money gives Kit an easy way to think about Diane. She thinks Diane has had it easier than, in the end, is the case.

LM: How do you think about your readers? Who do you write toward?

MA: There’s no specific reader in my head. I think about telling stories in a bar before last call. I want it to be the most exciting story, and I want the feelings to land. I want to be true. When I think about endings, I think about two types of reader. Some people need the ending to play fair, which means I have to answer the book’s main questions. Others need an ending that’s emotionally satisfying, that leaves room for ambiguity, and lets the reader bring him- or herself into the book. I think about those two kinds of readers, but other than that, I’m just imagining a person next to me at the bar, and hoping I can tell a story well enough that they finish a bottle of bourbon with me.