Lit Mags

Nothing Like a Lockdown to Lock Down a Relationship

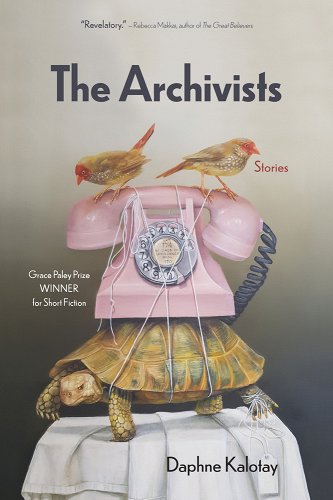

"Communicable" from THE ARCHIVISTS by Daphne Kalotay, recommended by Rebecca Makkai

Introduction by Rebecca Makkai

Like Lewis Carroll’s White Queen, I’m always looking for impossible things. When a story manages to pull off something that by all logic shouldn’t work, I’m thrilled and floored. And by my accounting, Daphne Kalotay does four impossible things in “Communicable” from her new collection The Archivists.

First: She writes a story about the pandemic without making it just a story about the pandemic. We’ve all been so nervous, over the past few years, about writing “the present,” a time we used to be able to gesture at vaguely and universally. For three years, we’ve either had to be specific (who’s masking, how are people meeting up, are they talking about it) or ignore it altogether. In the stories that do acknowledge the present, pandemic details often feel tacked on—or else they steal the show. But what Kalotay does is remarkable: She uses the pandemic as an organic plot device, writing a story that could only happen in lockdown—COVID is at the very center of the story—and yet it’s all simply scaffolding to the real story, which is about people who are both pushed together and falling apart.

The second impossible thing: Kalotay writes a story where not much happens, and makes it riveting. The actual events of the story are minimal—but there’s enough danger, enough forward tilt, enough that’s mysterious and ominous and desperate, that we’re going to keep reading.

Third: She separates characters via technology, and not only makes the conversations work, but makes them work as they never could in real life. I’m always telling students not to separate characters by phone or computer, and here’s Kalotay proving me wrong. It’s safe to say this is not only the best Zoom-dependent story I’ve ever read; it’s a story that’s made better by Zoom.

And the fourth impossible thing (with a mild spoiler): She writes a story in which a character is unaware of herself in some fundamental ways, but in ways readers are oblivious to as well. We’re not sitting back thinking that we’re watching someone come unhinged, questioning their narration… until, at the very end, we have to face reality alongside her. In lesser hands, it would feel like a gimmick. Here, it feels entirely earned.

To cap it all off, Kalotay makes it look effortless—it’s the kind of story you have to imagine the author typing in one go, while drinking tea and watching birds. I have no doubt that the real labor and delivery of this story was far more complicated and painful, but then again, I’m in the mood to believe impossible things. So, I choose to believe that she wrote the story as quickly and eagerly and entirely as I inhaled it.

– Rebecca Makkai

Author of I Have Some Questions for You

Nothing Like a Lockdown to Lock Down a Relationship

Daphne Kalotay

Share article

Communicable by Daphne Kalotay

The first time it happened—though she didn’t exactly take note—was when the plumber reemerged from the basement to report that the water was back on. He wore the kind of mask that protruded like a snout and kept to the border of the kitchen, directing his comments only to Leland, though Marlo had been the one to make the appointment and usher him inside. As though Leland really were the man of the (rented) house and not a lover arrived just days ago. Marlo watched from the heavy oak dining table that had become her office, wearing knit fingerless gloves to compensate for the feeble heating. Something fluttered just beyond her knee. But when she looked, there were only the scratched wooden floorboards, with dark knots like misshapen eyes.

“I’ll see if we’ve got the part in stock,” the plumber said. “With shipping delays, orders are taking some time.”

From behind his own mask—of wrinkled fabric—Leland asked about using that bathroom. He had a habit of hunching his shoulders to accommodate those shorter than himself, and against the persistent chill wore the padded jacket a friend had given him—apparently retrieved from a dumpster, washed, and, failing to fit his friend, handed off to Leland. It was deep blue like his eyes, with sleeves a half inch too short. His wrists poked from the cuffs, making him look as much a child as his true age of thirty-six. While the plumber delivered what to Marlo seemed a preposterously lengthy response to a simple question, Leland nodded along, pausing to tug the cotton mask back up to the bridge of his nose. In their weeks apart, Marlo had often pictured him—the tousled hair, the violet flecks in his eyes—and the word that came to her was dreamy. But with the mask, his eyes looked severe rather than a frankly penetrating blue.

It was as he again reached up to adjust the mask, hiking the somehow ludicrous jacket above his waist, that she saw another shadow. More like a flicker. The moment Marlo sought it, it disappeared. She glanced at the overhead light. The house possessed many quirks. Marlo had found it online, through a real estate agent, after everywhere she could afford had been snatched up. She had waited too long to leave the city, hesitated even as provisions dwindled and hospitals filled—had put off her decision because of Leland.

They had been dating only a few weeks before the lockdown and when Marlo finally left had slept together only twice. The first time was the night before the email from Marlo’s company directing employees to bring home all they needed to work remotely. And as Marlo filled a cart with cans of soup, sacks of rice, and dried beans precious as ancient beads, her next thought, beyond panic, had been, Will I ever see Leland again? He lived with roommates in a fifth-floor walk-up on a grim street down by the Manhattan Bridge. With fears of even a shared subway car, the distance between their apartments became a vast and perilous gulf.

Now, she watched him show the plumber out and checked the time. Marlo was director of marketing for a company that designed office furniture, and endured daily meetings with her boss (a mildly infuriating man who had already contracted the virus and survived). Leland ran his own nonprofit, the Community Project. In normal times he spent his weekends documenting whatever activity he had organized (pop-up tuba concert; barbering classes; painting murals on a stretch of city street), to post clips on his social media accounts. Marlo usually found such look-at-me behavior cloying—but this was to bring in donations. Leland’s posts garnered hundreds of hearts. He also belonged to an online network of people who recycled their belongings not simply to reduce waste but also to avoid spending money. If someone needed a new cellphone, say, they asked if anyone had an old one to give away. Same for sofa beds, wrapping paper, wart remover. No request was too large, small, or strange. Marlo knew this because Leland had invited her to join the network, where she saw people posting photographs of trash on a street corner: Found this free armchair, just missing one foot! with the geographical coordinates, no seeming worries of bedbugs or otherwise. Leland and his roommates had furnished their entire apartment via the network—perfectly nicely, though Leland had no mirror or desk. Marlo couldn’t help wondering, if he were ever to give her a gift, if it would come from this list. But four years had passed since her divorce and she was tired of the dating apps, the disappointments. She liked Leland’s energy, his keen mouth and hands that even the first time knew just how to touch her, and wanted to do things differently.

“Here, fuel to get you going.” Leland had removed his mask and slid a bacon-cheddar scone before her.

She was supposed to curb her salt intake due to high blood pressure, but she didn’t want to sound defective; she took a bite. “Mmm, delicious.”

Yawning, Leland took a seat across from her. Marlo reached over to wipe the residue of sleep from his lashes. “Trouble sleeping again?”

“Yes, but it doesn’t bother me.” An edge to his voice. Apparently, he had experienced insomnia for years.

“I was hoping the country air would be a soporific.” She said this even though she herself found the bedroom somehow unnerving. She wondered if Leland had noticed the strange feeling in the room but hated to mention it if he hadn’t.

He said, “The key is not to stay in bed if you can’t sleep. That way you don’t associate the bed with lying awake.”

Marlo had been aware of Leland leaving in the night. “What do you do when you get up?” She had been wondering this since his arrival two days earlier.

“Read, or stretch, wait until I feel sleepy again. Last night I did some tai chi.” He took a sip from his coffee mug. Like Marlo’s, it was glazed a morose shade of green and chipped at the brim. “In the past, some women I was with weren’t able to deal with it.”

The mention of previous women had her sitting up straighter. “You mean—your insomnia bothered them?” (It bothered her, too, but she was determined to acclimate.)

“I don’t know exactly. They decided they weren’t comfortable with it. You know how some people are.”

Some people. Informing Leland about the rental, Marlo had been ashamed—at her desperation to escape her sleek building (especially the elevator), and at how easily she had shelled out no small amount of cash for a scrappy cottage three hours from the city. She once heard a friend say of her that she threw money at problems. Marlo was single, childless, and made a good salary—not to mention the divorce payout, after Reggie’s affair with a paralegal from his firm. The staggering shock, after six years of what she thought to be a happy marriage, was worth something after all. Marlo did not live grandly, but if something broke, she paid someone else to fix it. If disaster struck, she bought a ticket out of it.

Yet money could not mitigate the fundamental awkwardness of being thirty-nine years old and dating during a plague. It was hard enough getting to know someone new. Frightening, even. Marlo’s friend C.J. had already told her she was moving too fast with Leland.

She said the virus was a perfect excuse to slow things down.

“But I’m afraid of losing him.”

“Lose him—where’s he going to go? The entire planet is on lockdown.”

“We’re just getting to know each other. If we don’t stay close, he could lose interest.”

“Shouldn’t you be focusing on figuring out how you feel about him?”

C.J. was such a killjoy. No wonder she was still single.

It was Marlo’s main partner at work, Pamela, who convinced her to invite him—not that Marlo would have admitted it to anyone. People thought Pamela was batty because she did things like claim to be mildly psychic and, if a coworker ever did something obnoxious, sent the person a forgiveness memo stating why the behavior had been hurtful and that this memo is meant to be open and forgiving because she believed that failing to be truthful about one’s feelings caused them to manifest in other, harmful ways, drawing out residual emotions lingering in the atmosphere—to say nothing of the fact that, upon receiving the company email about the building closing due to the virus, she had used Reply-All to urge everyone to rinse their sinuses with a mixture of salt and lukewarm water. She had also, once, refused outright to work with an employee she claimed had conducted himself deceitfully. Actually, Marlo privately admired her for that. Another time, Pamela declared herself unable to work on a textiles partnership because she had a bad feeling—and, sure enough, the textile company’s owner was accused of embezzlement. In her late forties or early fifties, Pamela was VP of communications and had an enviable aura of calm about her, plus she was brilliant when it came to marketing campaigns; probably her uncanny ability to read people was what she meant by psychic. She was the person who, during team brainstorms, would serenely watch everyone work themselves into a corner, and then suggest, Or we could just . . . Always something simple yet right—which, Marlo supposed, was how she got away with all the nutty stuff.

Marlo and Pamela worked in tandem and often chatted together before and after meetings. Soon after Marlo had bought the used Honda to relocate to the farmhouse, she found herself telling Pamela, at the end of one of their calls, about Leland. Was it too soon to invite him along? Friends told stories of boyfriends who turned out to be nightmares, or simply annoying. Either way, it scared her.

Pamela said, “Listen to your intuition, not your fear. Intuition allows us to take action. Fear paralyzes us. Let it be you deciding—not your fear.”

Taking another bite of scone, Marlo decided she would simply tell Leland she liked less salt. Easy enough. Problem solved.

The shadow-flickers returned a day later while she was on a call for work. On-screen her coworkers appeared less polished, some with unmade beds in the background, some with pets, small children, sulky teens sidling up, to be briefly indulged then swatted away. Her sales strategist (huddled in a laundry nook to escape household noise and her children) was constantly having to tell her youngest, Not now, sweetie, I’m on a call. And each time Marlo glimpsed his little head entering the frame, a pang went through her, at not having her own child to sweetly bat away.

She hadn’t dared tell Leland she hoped to have children, for fear of scaring him off. She hadn’t told him about the painful, expensive process she had undergone to have her eggs extracted and frozen.

You know Marlo: throwing money at a problem . . .

What would frugal Leland make of an extravagant medical procedure for a purely hypothetical possibility?

Her friends found it incredible that Marlo had yet to hold the do-you-want-kids conversation with Leland. Was it the fact that Leland had yet to ask her? She hated to sound like one of those women simply looking for someone—anyone—to father a child. There was also the matter of her true age, which Leland did not yet know. On the dating app she had entered her age as five years younger, since everyone told her men wanted younger women. And it turned out to be true, the men who chose to meet her uniformly believed themselves older than Marlo. She had intended to tell Leland her real age the night she met him—but by the time she remembered, that fact, too, felt like something she needed to introduce at the right moment.

On the dating app she had entered her age as five years younger, since everyone told her men wanted younger women.

“For the semi-opaque ones, I’m thinking something like ‘Refuge’?” her marketing manager said. He wore his signature bolero hat with a blousy silk shirt unbuttoned to mid-sternum, so that some wispy chest hairs were visible. Though still in his twenties and possessing no great talent, he had been prematurely promoted, apparently because he reminded their boss of the younger version of himself.

From the laundry nook, her sales strategist said they needed something less literal. “What about ‘Aura’? Like a cloud, rather than a divider.”

Because of the virus, they were having to reconceive their entire product line. Community spread meant no more shared office spaces, no more hot desks. When people returned to work, it would be in cubicles, as if it were the nineties again. Today they were naming a line of plexiglass partitions easily erected between desks.

Marlo watched as the marketing manager pontificated in front of what looked to be a professionally stocked bar. The sales strategist had turned her screen off, which meant she had at least one child seated on her lap. Pamela sat in calm solitude before a bed on which posed a subtly shifting black cat.

“Mar?” Leland poked his head in, hair mussed in his youthful way. “Have you seen my jacket?”

Marlo smiled, gave a little shake of her head; he would understand she was in a meeting. Leland whispered, “Sorry!” and disappeared from her view.

Something flickered at Marlo’s elbow. She kept her eyes on her monitor. “Okay, how about these ones with storage?”

As possible names were tossed back and forth, Marlo involuntarily checked her hair in her little box on screen. (There was only so much longer that she could keep touching up her roots; soon she would have to re-dye, risking Leland noticing.) She swept a stray lock behind her ear. Though she no longer wore her sleek jackets or sharp-heeled boots, she still used a hair iron and eye makeup before her meetings. She could not imagine attempting her role without them.

Meanwhile, these men with their five-o’clock shadows and unmade beds . . . and the marketing manager with his stupid hat and bare chest . . . When he turned off his video, his black box was replaced with a photograph of him in semi-profile, wearing sunglasses (though the photo was clearly taken indoors) and the flat-topped hat but with a different—tapered—shirt, also unbuttoned to the level of his nipples, his chin angled dramatically toward his shoulder, his one visible eye peeking over the rim of his shades. If Marlo used a picture like that—if she wore a bolero to work with her blouse unbuttoned down to her bra—she would be laughed out of town!

The sight of the photo, like the hat and unbuttoned shirt, brought on the same low-grade resentment she could not help feeling at Leland’s ill-fitting jacket—that he could wear a coat found in the trash and be taken seriously, while she had to iron her hair and swipe on eyeshadow. On his video calls Leland rotated the same two faded button-down shirts, plus the scrappy padded jacket, without being mistaken as destitute or insane.

What about the young men his program helped? she wanted to point out. Would he send them to an interview in threadbare shirts and too-small jackets and expect anyone to give them the time of day?

“File-r-upper . . .” the marketing manager was saying.

“Smorgasbord,” said her sales strategist, hunkered in the laundry nook.

From the hallway, Leland pantomimed: Could he borrow the car? Adding, in a half-whisper, “Must’ve left my jacket at the post office.”

Marlo pointed to where her purse (which held the car key) hung from the doorknob, as something flitted past her hip and a notification popped up on her screen. The network, someone in her neighborhood in the city asking if anyone had a spare desk. Even with the nation wiping down groceries with antiseptic cloths, leaving mail to sit for forty-eight hours, people were still exchanging items.

Marlo clicked the notification away, trying to focus, as Leland thanked her and left.

When at last her meeting ended, she and Pamela purposely lingered. Pamela looked tired. She asked Marlo about life in the country and, when just the two of them remained on-screen, “How’s it going with Leland?”

“Great—really well!” Marlo told her how it felt to have his help shopping at the grocery store, Leland keeping a place in the long, slow queue while Marlo foraged for flour, bouillon cubes, boxes of pasta in strange shapes that were all that was left on the shelves. Back at the house, lathering their hands under the rushing spout as hurriedly as if they had touched a corpse, Marlo felt, she half-joked to Pamela, like a real couple!

But something on Pamela’s face looked—what? Disappointed? As if she didn’t quite believe it? Perhaps Pamela was envious. After all, she was a good decade older, not to mention still single. Marlo asked, “How are you holding up?”

“It’s been hard. Home alone, day in and day out.”

This was something else Marlo liked about Pamela. Never the reflexive Fine, and you? Marlo wished she could be like that.

Pamela said, “You know, I’m used to a balance of solitude and socializing. I had the perfect life. I sang in a choir, I swam on Mondays, took a blacksmithing class on Wednesdays—”

“Blacksmithing!”

“—and Friday was Lindy Hop night. Now all that has evaporated. Sometimes I’m just . . . sad.”

Her voice through the computer audio was hollow. As if her voice, too, were caught in a square black box. Marlo wanted to reach out and hug her. She felt herself about to invite her to join her and Leland in the country house. But no, that would be crazy. She said, “That sounds tough.”

Pamela said, “You were smart to invite Leland to come out. Everyone who has someone with them right now is lucky.”

“Well, except for people stuck with people they can’t stand.”

“True,” Pamela said. “The grass is always greener.”

For a horrible moment Marlo imagined herself alone in her own apartment, without Leland to accompany her through the torrent of emails, the online meetings that managed to bleed into every hour of the day. With everyone working from home, she now found herself scheduled for meetings at all hours, five in the morning with a London distributor, seven thirty in the evening with the Seattle sales team . . . To go through this alone, no one else in her box of an apartment to turn to, would be hell.

“I do feel lucky,” she told Pamela. And though not usually superstitious, Marlo rapped on the wooden chair, just in case.

She asked Leland about children on a suddenly warm afternoon on the south patio. While the north side hadn’t yet shaken the bleakness of winter, here one could feel the sun and watch bumblebees dawdle in the bushes.

She was glad to be outdoors. To escape the eeriness that lately seemed to have spread throughout the house. Something not quite right . . . Though she tried to tell herself it was nothing, the sensation affected her concentration—just when she needed to prove herself, with the consolidations at work. Yet she hesitated to mention it to Leland, wanting to preserve the even rhythm they had created. Also, it was the kind of thing some eccentric spinster like Pamela would say.

In the sunshine, her unease floated away. Marlo felt less burdened. Reclining in the wicker chaise, laptop balanced on her thighs, she was mid- email when a shadow-flicker swept through her periphery.

This time she took full note. “Did you see that?” she asked Leland, who was working at the wrought-iron table, munching on a cider donut from an orchard he had stopped at on one of his drives.

“No, what?” He wore the pale blue sweatshirt she loved, that made his eyes twinkle. In just over two weeks, his hair had reached his ears, thicker and lightly mussed, like a teenager’s.

Marlo indicated the area by her leg. “I thought I saw something.”

“Chipmunk? I think they’re planning a coup.”

It was true the chipmunks were hard at it. Each seemed to have its own fiefdom; interlopers were chased away in what looked like adorable skirmishes but were probably incisive territorial battles.

Leland held the bag of donuts out to her. She waived the grease-stained thing away. She couldn’t eat baked goods as he could, without repercussions. Leland was always bringing home bread products, having taken over most of the errands now that Marlo headed her company’s digital division, too. While Leland’s patronage of small-town grocers near and far was sweet, he had somehow managed, so far, to always let Marlo be the one to fill the gas tank.

Another shadow-flicker—quicker this time. Marlo knew it wasn’t a chipmunk. She was about to say, “There, see”—but stopped herself. She didn’t want to sound insane. She told herself it had to do with the way the sun was passing through the clouds. She looked up. There were no clouds.

Please don’t let it be eye trouble. Not now, when all the doctors’ offices were closed. Probably it was from too much screen time. The consolidations meant Marlo spent even longer hours on her computer. Not to mention that her boss had made her do the layoffs.

She tried to remember what the eye doctor had told her about torn retinas, or was it macular degeneration? Something about “floaters” or dark spots. Was that what these flickering shadows were? She couldn’t ask Leland. That sort of thing was an old-person problem.

She was suddenly terrified that there was something really wrong.

Leland yawned. “Time for my post-prandial nap.”

Marlo tried not to show annoyance. She had begun to suspect that his naps contributed to his insomnia. But the one time she suggested he try to push through, Leland had looked at her with affront, as if her insensitivity to his malady were a sign of hard-heartedness.

He also checked his cellphone in bed, though the light from such devices was known to interfere with sleep. He was always posting on his various social media feeds, to keep people engaged in the foundation while its activities were stalled, since he had lost some large donors. He called it the Keep Connected Campaign. Marlo had seen some posts: the gothic-looking turkeys, the solitary deer that liked to nibble placidly on one unfortunate tree, a garter snake peeking out from a rock . . . Leland did not feel the need to hide his abandonment of the city. He came up with comical tag lines for his photographs (for the turkeys: Sure, it’s beautiful, but I miss the city—here no one ever seems excited to see us) always with a link to the Donate button. Apparently, each brought in a slew of small donations.

Was that what he worked on in the wee hours?

A chipmunk, cheeks bulging, ran right across Marlo’s foot. They really were cute. Marlo watched it scurry to the stone wall to fit itself into a dark little hole, its perky tail upright like a flag. And in that moment, Marlo managed to blurt out, “Have you ever thought about having kids?”

“Yeah!” Leland said it brightly, as though recalling a fun leisure activity. “I’ve always thought it’ll happen however it’s meant to happen.”

Men could do that, wait and see. Her ex—six years older than Marlo—had done that. He and the paralegal (whom he had gone ahead and married) now had twin daughters they dressed in absurd matching outfits. Never mind that the paralegal had been a subordinate; Reggie’s indiscretion had not prevented him from making partner at the firm. He got the whole enchilada, as C.J. had put it.

C.J. always knew how to make Marlo feel a blow.

Pamela had told Marlo she needed to rid herself of her resentment. That if internalized, it would warp how Marlo viewed the world. Of course, Marlo would be the one whose attitude had to change. Not cheating, paralegal-poking Reggie. (While Pamela could outright refuse to work with that guy she no longer trusted, and completely remove herself from a project based on a negative feeling!)

Marlo was prepared for Leland to ask if she wanted children of her own, but his phone pinged. Though his projects were stalled, he still fielded plenty of calls.

He reached over to give Marlo’s hand a squeeze. “Sorry, Mar, I have to take this.”

His phone was a small, refurbished one acquired through the network. As he spoke, Marlo secretly congratulated herself: she had asked the dreaded question. The answer wasn’t anything other than what she ought to have expected. She needn’t worry anymore.

When she and Leland went walking together, they rarely saw a car, let alone another human, just the occasional fleeing deer, or a hawk lifting with the wind, or cows whose tails spun like dials. If they did cross paths with someone, it was usually the old man at the farm down the hill, standing at the opposite side of the road to chat while his three dogs barked ferociously from behind an invisible electric fence.

Leland asked the man about the house they were renting, where the owners had gone.

“Been empty a good year now. Guy had a landscaping business, but must’ve had trouble. One day he up and left. Wife and kids, too.”

When she and Leland continued on their way, Marlo wondered aloud if the couple still owned the house, whom exactly her rent went to.

“I wonder if they’re still a couple,” Leland said. “Maybe they were splitting up.” He slung his arm around her. “A few of my friends are going through that now. Relationships I thought were rock solid. But I guess after a certain amount of time . . . who knows. Must be rough.” He let go to pick up a bright rose-colored stone from the road, examined it, tossed it aside. “What about you? Know anyone who’s been through a divorce?”

Marlo kept her eyes on the pebbly road before her. The problem was that when your husband left you for another woman, it sounded as if you were insufficient—a reject. She said, “No—well, maybe I should say not yet.” She tried to laugh.

“Yeah, well, you’re a few years younger than me. Give it some time.” Leland took her hand in his. She held tight, as noisy birds clamored in the trees, and said nothing more.

Later, at home, Marlo thought about what the man down the road had told them. It made sense that the family’s finances hadn’t been good, when she considered the state of the house—the weak plumbing (the part for the toilet had arrived only last week), constant draft, whole place needing a fresh coat of paint. She always emphasized these facts in her phone catch-ups with C.J., who had gone to take care of aging parents in a house in Vermont and sounded cold and lonely. Bitter, too; her brother wasn’t helping one bit. Marlo had told C.J. about searching for a plunger in the basement and discovering a stash of empty vodka bottles—twenty, thirty of them—behind a panel near the washing machine. Dusty, some covered in cobwebs. Was this why the landscaping business had gone under? “Someone was hiding their drinking problem.”

“Drinking while laundering,” C.J. joked. “Depressing.”

“Leland brought them to the dump. He says the important thing is to take action, not get emotional. When I’m heartbroken over the news, he talks me down. It’s such a breath of fresh air compared to what I’m dealing with at work. They just furloughed another fifteen percent of the company. Leland makes everything seem manageable.”

“He’s your knight in shining armor.”

Marlo couldn’t tell if C.J. was being sarcastic. She decided to keep the tender moments for herself. The (loving?) way Leland held a buttermilk biscuit to her lips on one of her now nonstop days. Eyes lighting up when she emerged from her shower, as if she were an odalisque and not a nearly forty-year-old in a fuzzy blue bathrobe. Dancing around together to old rockabilly songs when they cooked dinner, how he paused to brush her hair from her face and kiss her.

She wondered what small, unconscious actions she might have taken that pleased him without her knowing it.

“How’s his insomnia?”

Of course C.J. would go there. Marlo explained that though he still had some trouble, after nearly five weeks of this, it no longer disturbed her. “I mean, half the time the coyotes wake me up.” There was a wolf in the pack now, she had noticed. A lower, deeper howling than the others.

Sometimes, seeing the empty spot in the bed, the void seemed to chide her—for all she still did not know, did not understand, about this person she wanted to be close to. As if it were some error on her part. That if it weren’t for the lurking unpleasantness of this room, of this house, Leland would be here in bed beside her.

Sometimes, seeing the empty spot in the bed, the void seemed to chide her—for all she still did not know, did not understand, about this person she wanted to be close to.

One day, Marlo noted something to perhaps support this notion. It happened during a work meeting, the morning after Leland’s question about divorce. A shadow flickered near her elbow. And on-screen she saw—was certain she saw—Pamela’s eyes dart to where the shadow-flicker had been.

She saw it, Marlo thought with a jolt. Saw, and then couldn’t see—just like me.

There was no time to chat after the meeting, and Pamela didn’t mention it. But Marlo had seen her eyes. This gave her confidence to say something to Leland.

She waited until dinnertime—Leland’s spaghetti, steam rising into the chill air. “Don’t you think this house has a weird energy?”

He was twirling his noodles around his fork, a miniature hay bale. “What do you mean?”

Marlo felt a small deflation, that he had not picked up on the strangeness. “I think something happened here.”

Leland seemed to really be thinking. “You mean—because of what the plumber said?”

The plumber. When he at last returned with the missing part, Marlo had noticed the way he paused in the entryway to glance around the combined living-dining room, as if looking for something. She had ventured: “Did you know them?”

“Family that lived here? Nah. Must’ve been doing their own plumbing. Or trying to.”

“Did something happen to them?”

“Other than the business failing? Not that I know of. Small enough town, I’d hear about it. Cops had to come here a couple times. Wife was a screamer.”

Marlo stared at him. “What do you mean?” She asked even though she wasn’t sure she cared to hear his answer.

“Guess they liked to bring the local brass into their marital spats. Some folks like an audience.”

She didn’t like the plumber at all, then.

To Leland she said, “Maybe that’s what I’m thinking of.”

Because anything else would just make her sound like a madwoman, and she didn’t want him to think of her that way.

By mid-May, peonies were blooming on the east side of the house, heavy wadded pink clumps. Marlo cut stalks to bring inside. Despite the signs of spring, the air still nipped at them; Leland wrapped himself in a wool blanket (he never had found his padded jacket), and Marlo still wore her fingerless gloves. The peonies leaned in a tall vase near her desk so that their sweetness infiltrated her meetings. The petals crawled with shiny black ants.

Today’s meeting was just Marlo, the marketing manager, and Pamela; to Marlo’s dismay, her sales strategist had been furloughed. Worse, it seemed she did not intend to return. With her children home, and summer camp likely to be canceled, and who knew about school come fall, she said she could no longer do two jobs at once.

She was probably right about school. Today’s meeting was for the company’s “At School At Home” campaign—office furniture repackaged for domestic use. Secretly Marlo wished the marketing manager had been furloughed instead. If you told him (twenties, single, childless) you needed him at a sales conference in Grand Rapids, he would make a wincing sound and say, “You know, I just don’t think I can fit it in.” Whereas her sales strategist (thirty-seven, three children) would take a long deep breath, pause, and say, “Okay, I’ll see what I can do.”

Marlo’s favorite graphic designer, too, had been let go. She was a single mother with two young sons, one of whom had some severe condition that required him to live in a residential facility, which had closed due to the virus. Marlo had no idea how she was managing.

On small calls like this, Marlo liked to arrange her screen so that she could view everyone at once. Through the open dining room window came a robin’s expert whistling, and the cute interrogative whine of goldfinches.

Not now, sweetie.

Even in the warmer weather, the marketing manager wore his bolero hat, with a shiny blue shirt unbuttoned to mid-chest. Marlo adjusted her earbuds as Pamela said, “We want to sound upbeat but not false. None of these kids want to be home.” Behind her the cat, regal, eyed the camera distrustfully.

Marlo heard the door open. Leland must have woken from his nap. He asked if she had the car key.

She turned to give him a quick wave and indicate her earbuds. Her purse, in which her keys were buried, hung from her chair, but something stopped her.

“Sorry to interrupt,” Leland whispered. He pointed to her purse as he approached her, made a key-like gesture. Pamela said, “Is that Leland? Handsome!”

“Yes!” How proud it made her, to be able to say, Yes, he’s mine!

As he hovered behind her, Marlo reached into her bag for the keys, tossed them to him. A pillow-crease marked his cheek. He thanked her and ambled out.

“So that’s what lured you out to the country,” the marketing manager teased.

But something was happening to Pamela. She was no longer smiling. Her eyes were blinking. Her mouth was open. She seemed to be staring at something.

“Pamela?” the marketing manager asked.

Marlo looked behind her. There was nothing there. “Pamela,” Marlo asked, “what do you see?”

Pamela rolled her chair backward, as far from her desk as possible. The chair bumped the bed, startling the cat. It leaped away, off-camera.

The marketing manager said, “Is there something happening on the news? Is that what you’re watching? Marlo, are you on Facebook? I’ll check Twitter.”

“No, I’m not,” Marlo snapped. “Pamela, what’s wrong?” But Pamela’s little on-screen box disappeared.

“I’m messaging her,” Marlo said, as her marketing manager, scrolling through his phone, said, “I’m checking my feed, there’s nothing happening.”

“Let me call her.”

There was no answer. No one was able to reach Pamela for the rest of the day.

It was like she was hallucinating, they explained on their group call the next day, when Pamela still hadn’t returned any messages. Though one of the designers who lived in her neighborhood had tried to check on her (at Marlo’s urging), Pamela hadn’t answered the intercom. When Marlo suggested contacting the police, their boss said it was Friday, “let’s give her the weekend—you know how Pamela can be. She logged off on her own, so she hasn’t had a stroke or anything. Maybe she just needs some time.”

The fact was, everyone seemed to have expected this. Hadn’t Pamela always been crazy? Clearly pandemic isolation had driven her over the edge.

Meanwhile, ever since that day, Marlo had been seeing, all around her, the flickering shadows. They gathered round in swarms.

She never had spoken to Pamela about the shadow-flickers. Since Pamela hadn’t mentioned them, Marlo hadn’t dared ask what she had seen that one time. Now she tried to recall if those circumstances had been similar. This time Pamela had seen Leland walk in, and then: what?

She tried texting Pamela again.

I’m worried about you. Do you need help?

Silence.

There was no sign of Pamela on Monday. But when Marlo asked about contacting the police, her boss said he had managed to reach Pamela and not to worry—then refused to say more. Marlo forced herself not to dwell on it. But by Friday, when Pamela still hadn’t returned, Marlo, desperate, called her boss to ask, “What’s going on?”

“Oh, I meant to tell you. Pamela got in touch a few days ago. She decided to take the severance package.”

The early retirement package being offered to more senior employees, to help reduce overhead.

“You mean, she’s not coming back?”

“No, she said she’s done here.”

It was a slap—a punch. “But—”

“She said she’s been wanting to start her own consultancy. That this way she could take a break first. Have a rest.”

It was true Pamela had mentioned wanting to go out on her own—but now surely was not the time!

Marlo immediately texted her.

Are you okay? Know that you can share with me what happened.

And hours later, when Pamela had not responded:

Pamela, you can tell me what you saw.

All week, the flickering shadows had grown so frequent, so teeming, it seemed impossible Leland didn’t see them. But he sat peacefully at the other end of the dining table, typing into his laptop, the fuzzy wool blanket wrapped around him.

When she could no longer stand the shadow-flickers darting round, Marlo typed:

Pamela, if what you saw has to do with me or Leland, I beg you to tell me.

The reply came within minutes.

You haven’t been forthright with him

Marlo stared at the message. She was considering how to respond when Pamela wrote again.

Rage attracts past rage

Lies breed & proliferate

Marlo turned off her phone. This was no time for that kind of crazy talk.

“You okay?” Leland placed his palm on her forehead as if taking her temperature, then leaned down to kiss her before taking a seat next to her.

“Pamela quit.” She could hear her voice shaking.

Leland gave a tsk. “She have kids at home, too?”

“No, she’s not—”

“Oh, right, the kooky one.”

They were Marlo’s words, yet they sounded wrong. “She wasn’t just kooky.”

“I meant . . . isn’t she the one who, like that time someone was dishonest—” Leland stopped himself. He leaned back, away from her.

Marlo felt herself stiffen. “Yes,” she said, “all of that nutty stuff.”

Leland slid his chair back. The violet flecks in his eyes looked like sparks. For the briefest moment, Marlo was afraid of him.

“She took the early retirement package,” Marlo said quickly.

Leland said nothing. Marlo could not look at him. She looked down at her phone with its darkened screen.

At last Leland said, “Well, I guess that would explain it.”

“Yes. I suppose I’d take it, too.”

She dared to look up. Leland’s gaze pinned her to the chair. Marlo said, “More work for me. Yippee.”

Leland gave a quizzical look. When Marlo looked away, he said, “Just don’t burn yourself out.”

That night in bed, the coyotes woke her. It always happened this way, a single coyote’s cry, then another’s excited yapping, and another, as if the yowling were contagious. In her half-sleep, she envisioned the house’s former owners out there, somewhere among them, howling.

Wife was a screamer.

She could hear the wolf now, too, its deeper howl. Rolling to her side, she saw that Leland had left the bed.

The skirling outside was wild, pagan. What had they killed out there?

“Do you hear that?” she called to Leland.

She threw back the covers. The floorboards were cool and rough, and she hastily pulled on her socks before stepping out to the dark hallway. A dim light issued from around the corner. She followed it, to the door that led to the basement. “Lee?”

The bulb above the basement stairs had gone out. The only light came from below, a dull amber glow. Marlo waited for her vision to adjust before finding her way down the steps—wooden slabs that gave small groans under her feet.

A single yellowish lightbulb left most of the basement in shadow. Across the room, past the washing machine, a figure hunched over something.

In the dusky shadow the figure became Leland. He was kneeling, crouched in a posture that at first confused her. His shoulders sloped, his head bowed over what seemed in the haze to be a torso.

Leland looked up. In a pained voice he asked, “Why did you hide my jacket?”

For a moment, Marlo could not speak. She found she could barely breathe. How could he not see why—though she struggled, now, to find words to respond to his question. Even in the dark she could not look at the jacket. She asked, “How did you know where to find it?”

He gestured at the crawl space where she had found the vodka bottles those weeks ago. “Isn’t this the hiding place?”

The shameful place. Everything she hadn’t dared say aloud. Her resentment, her lies. He had sniffed them out.

“I’m sorry, Lee. I don’t know what I was thinking.” She realized she was whispering.

He was still crouched on the floor, shoulders drooping. Calmly, he said, “I’d like to try to understand. But right now I just need to figure out what I want to do.”

She felt her heart racing, chasing after him. “Please don’t leave me here.”

“I just need to borrow the car and take a drive or something. Clear my head.” He placed the plywood cutout back over the crawl space. Stood and brushed the dust from his pajama pants. Tenderly, he draped the jacket over his arm. Then he walked past Marlo, toward the stairs, without looking at her.

In the amber darkness, she watched him make his way across the room. With his long limbs, his pajama pants exposed his knobby ankles, visible only as he passed close enough to the light, before darkness hid them again.

She watched him retreat back up the steps. The squeak of each wooden board was like a tiny cry. Around her, the shadow-flickers gathered, flitting frantically back and forth. She stroked them, and caressed the tops of their heads, before swatting them away.