interviews

Translating the In-Betweenness of the Immigrant Experience

Activist-novelist Jessica Gaitán Johannesson discusses the connections between language, migration, and climate justice

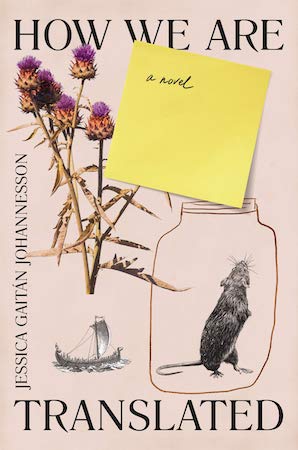

“Surprising … Rising from the surp. What is a surp anyways?” The narrator of How We Are Translated by Jessica Gaitán Johannesson questions. The Swedish word for “surprising,” on the other hand, translates to “överraskning”—which, when taken apart into “över” and “raska”—literally translates back to English as “to trod over something.” Word games like this are scattered throughout this debut novel; How We Are Translated formats its many Swedish-English translations into columns, comparing them side by side and using them to illuminate quirks about the narrator’s headspace. Johannesson nimbly plays a game of linguistic telephone, breaking words apart and filtering them through different languages.

A 24-year-old Swede who recently immigrated to Edinburgh, Kristin can’t stop thinking about language. Johannesson’s introspective and rambling narrator certainly has a lot else on her plate (and Kristin might question here: is this an idiom that exists only in English?). Her partner Ciaran wants to immerse himself in Swedish and refuses to speak English. Her workplace, the National Museum of Immigration, is going through a series of bizarre changes—as if working as a Viking reenactor at a tourist attraction wasn’t surreal enough; Kristin spends her days milking unhappy cows and pretending not to understand English, so that the tourists can have an authentic experience. And, sooner or later, she has to decide what to do about her potential pregnancy.

Johannesson’s novel acutely points out how “translation” isn’t simply about carrying one language over to another; it’s about how we are constantly translating one another’s words to communicate with each other, and translating our own desires to make sense to ourselves. Taking place through just one eventful week in Kristin’s life, How We Are Translated probes at the messy intersections between immigration, language, reproduction, and our constructions of home.

Jaeyeon Yoo: How did you decide on the structure of this novel (particularly the columns!), and this way of presenting translations?

Jessica Gaitán Johannesson: I think it sort of comes from, more than anything else, my own multilingualism. I grew up speaking both Spanish and Swedish. So I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t bilingual in Spanish and Swedish; English is technically my third language. For a long time, when I was transitioning to writing creatively in English—about a decade ago, when I moved to the UK—there was this sense of imposter syndrome, basically, and a lot of [asking] was I allowed to write in English? What would that look like? With the novel, I eventually decided to lean into that in-between-ness by arriving at the character of Kristin, who is bilingual and, I suppose, really wants to belong. But, at the same time, she’s both outside and inside of a culture and a group of people in this place. So the structure itself came from that in-between-ness that came from: what would it look like to sort of inhabit my Swedish-speaking brain and my English-speaking brain at the same time? I think it’s fairly impossible to do it completely, but the columns and the literal translations and the hybrid view on language came from wanting to explore what it really means to live in several languages at the same time.

JY: You mentioned that you started creative writing in English around ten years ago. Were you writing in Swedish or Spanish before that? How was the process of choosing or beginning to write in English?

JGJ: I find it really fascinating to talk to other people about this. At least for me, there’s no straightforward answer, and it’s been fairly—I don’t want to say fraught—but definitely conflicted. I used to write in Swedish mainly. I was writing a lot in my 20s in Swedish and the first couple of poems and things I published were in Swedish. Then, when I moved to the UK, I ended up just staying. I did an MA at Edinburgh University called Literature and Transatlanticism, which is a program that doesn’t exist anymore. But it was totally fascinating because it was about looking at literature in terms of migration and connection, rather than studying American literature or English literature. So I’ve always sort of been interested in these [cross-lingual connections]. Then, I ended up living in English and breathing English and I met a partner who only speaks English. At some point, it just didn’t feel natural. It wasn’t possible to stay with both feet in Swedish. I had to at least try and write in the language that I was living in. That’s kind of the simple answer.

It’s such an interesting question because I’m just very aware and probably increasingly aware, as time goes by, of English being this all-consuming thing—as a colonial language and as a language of empire. I had to make the active choice to write in English. What does that mean, to leave a smaller language behind in order to write in English? That brings up a lot of different questions and there’s a loss to it, this sense of giving up on our responsibility. But, at the same time, we all own English; immigrants make English, people who speak English as a second or third language also own it. So I think there’s also a sense of diversity to English.

JY: RIght, there’s also a political question throughout, as your narrator notes, of what kind of language you can speak. I loved Ciaran’s quote in the novel about how “People don’t choose to learn English. It’s like smog.”

We live in a colonial world in which English has a very unique position to create insiders and outsiders and hierarchies.

JGJ: Absolutely. I mentioned responsibility and sort of asking oneself, what does it mean to leave a smaller language and to choose this all-consuming “smog” language? But at the same time, it isn’t necessarily a choice. You know, we all make choices within systems and within larger parameters. Weirdly, that kind of connects to a lot of what I’m writing about at the moment for my second book, which is climate justice, and this idea that all comes down to individual choice. And that’s essentially consumerism and individualism; we want to think that we all make choices, and that’s sort of the end of the story. But actually, the context is always different. We all have to make different choices within different contexts, and we make the choice to write in English—like, why English? Well, because we live in a colonial world in which English has a very unique position to create insiders and outsiders and hierarchies.

JY: Speaking of consumerism, I was intrigued by the performance of “authenticity” at Kristin’s workplace, this overt commodification of “foreign” cultures (like fika and IKEA). I wondered if you could speak more about these ideas that crystallize at the National Museum of Immigration?

JGJ: I’m so glad that those are the things that came up for you. On a superficial level, I’ve worked in tourism, places where multilingualism is commodified and a good thing to have. Those questions have always been there for a long time, like, yes, on the surface this looks like it’s celebrating a kind of internationalism and lack of borders and people communicating across cultures. But, at the same time, it’s very exclusive and commercial; it’s also got this idea of essentially the “good” and the “bad” immigrant. In order to belong here or to be able to stay, you have to contribute certain things. That’s the idea I ran with, which just kept snowballing and becoming more and more extreme—like now we have to do a parade [in the novel] to prove our cultural heritage.

JY: There’s a beautiful tenderness to this book that I found really special, particularly in depicting Kristin and Ciaran’s relationship. What does this relationship in the book mean for you?

JGJ: It means lots of things and the book certainly started with the relationship. The very core of the book for me is the idea of the future and of change, as in change of identity and change as anchored in our ideas of pregnancy. If you have the choice to become or not become a parent, in order to [give birth] there has to be a fundamental trust in the world and future—a sense of safety, you know, the world isn’t on fire sort of thing.

I just didn’t ever want to say, it is wrong or right to give birth… as if the very act of giving birth were tied to right or wrong for the climate.

For the main character, her safety is the small safety of having carved out home, having chosen a place to live, having this one person that speaks her language-beyond-language, if that makes any sense. They might not share a first language, but they have created a language together. They have all of these words that they use, like a lot of inside jokes and rituals, the way that intimate relationships work. So when her partner then takes control over the situation by saying, “I’m going to stop speaking to you in our language, but I’m going to somehow override you and and learn your language because I think that’s going to help,” that, for her, is him saying, “I don’t see you; I reject us and what is us.” One of the things that I find with moving between countries, being multilingual from the very beginning, and coming from an international family is that you’re never fully at home. You’re never fully a stranger, but you’re also never fully at home. So for him to say, “I’m gonna just speak Swedish to you.” She’s like, “But that’s not me, that’s not home” So, yeah, there’s a lot in there about what it means to know someone or what it means to see someone.

JY: I really resonated with what you said, of what it means to find a home in someone and make our own sense of belonging, within these larger systems of immigration and border control we’ve talked about. What little things we can do to keep our sense of agency or comfort, I guess.

JGJ: Yeah, yeah—and I think something that puzzles me and what I’m thinking about a lot in my second book is: where does community come into this? Because with characters like these—if your sense of belonging is solely tied to a small group of people in a private sphere, and also to a relationship that’s very heteronormative, where does community come into it? While writing [How We Are Translated], it partly also became an exploration of community. I wanted her world to expand, little by little, when she’s forced to look outside of her nest. So it’s like, there are these other people that I spend my days with—not just the Norse people [at work], but everyone else. She gets these little snippets from other kinds of lives, from people who have come to Scotland who are a lot less privileged than she is, and. So then she’s like, “well, do we all belong here? And do I have a sense of responsibility to this community, even though we’re not from the same place?” It wasn’t something that I set out with, but the idea of community became really key as I was finishing the book.

JY: You’ve alluded to this a few times throughout our chat and the novel, about the dilemma of creating life as the world is burning around us. I know you’re also a climate activist, so I wanted to know: how are climate activism and novel writing related for you?

A lot of people in the Global North are in a privileged position to not feel climate collapse yet.

JGJ: Oh, that’s such a great question. Which I don’t have an answer to. [Laughs.] But I can also talk about it for a very long time. It’s interesting you said novel-writing, because what I started writing straight after I finished How We Are Translated is a collection of personal essays, non-fiction, coming out in the UK in August. And the timing of those two books was quite weird. I’d finished the first draft of How We Are Translated by the time of the 2018 IPCC report—the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, the one that made all the headlines saying we have 12 years left and all of this stuff. I’d been involved with environmental activism a little bit before, but that report for me and my partner was what kind of threw us into climate activism, like headfirst. And I’d written this book about hesitancy concerning the future. What became quite important for me in the rewrites and editing was that I just didn’t ever want to say, it is wrong or right to give birth. I didn’t want to come out on any side and make it into a debate, as if the very act of giving birth were tied to right or wrong for the climate. As a climate activist, I’ve come across a really toxic narrative around birth and choice, one that sees non-birth as a strategy in limiting climate change, regardless of context and structural issues. [So] even though I’ve had huge debates with myself about parenthood in the face of climate collapse, I didn’t ever want to be prescriptive in the book. I didn’t want it to be a message about right and wrong, but rather that the way forward lies in community, of caring about where you are in the present and for people who might not be part of your immediate community.

JY: Yeah, for sure. This also really reminds me of another book I read by Julietta Singh, called The Breaks.

JGJ: Oh god, I love it so much. I was so inspired to read Julietta Singh’s book, because it dares to be actively hopeful about breakdown. She sees the breakdown as letting go of toxic narratives and embracing what comes after, you know? I was also deeply influenced by a book by an American scholar called Jade Sasser. She wrote a book called On Infertile Ground, which is about women’s rights and population control in the age of climate crisis.

I think a lot of people in the Global North are in a privileged position to not feel climate collapse yet. So, the idea of climate activism here is you go straight to bringing down emissions and CO2; it’s the science that comes first to mind. But if you look at things from a climate justice perspective, then you start to see that things like migrants’ rights and anti-racism and all of these things—and also reproductive justice—all these things are ways in which we tackle the climate crisis. Once I was thinking more along these lines, I realized that these are the things that form the very basis of [How We Are Translated]; the ideas of immigration and belonging are actually tied to the climate crisis. So, I sort of went on a bit of a circle and came back to [the novel] like, oh, yes, of course migration is about climate.