Books & Culture

What It Takes to Leave the Westboro Baptist Church

For Megan Phelps-Roper—and for me, leaving my restrictive Hasidic community—rebellion starts small

I’m often asked why I left the insular Hasidic community where I was born, bred, and expected to raise a burgeoning family. What was the impetus that led to this seismic shift in my thinking? How did I find the courage to rebel, and why? It’s also often these conversations that lead to well-meaning questions about why I did not feel oppressed or violated. How could you not have? they want to know.

It’s been over a decade since my husband and I left our community of birth, an enclave in upstate New York known as Kiryas Joel. The village boasts over 20,000 residents and an exponential birth rate. As the community continues to swell, so too does the list of restrictions. TV, movies, secular newspapers, books and the internet are strictly verboten. In the community leaders’ perception, the antidote to a progressing, modernizing world is an unyielding wall of strictures.

Throughout our slow transition, I’ve struggled to articulate a moment of awakening, which is what readers and audiences seem to crave. It was a composite of seemingly innocuous events, I tell them. Seeds of doubt planted did not sprout until years later, but they served to sear holes in my confidence. I began to question what I thought I knew to be right and righteous.

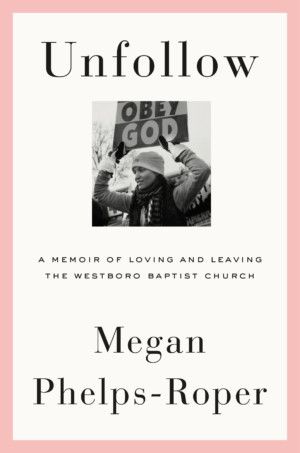

It’s this very struggle that emerged as a clarifying moment for me while reading Megan Phelps-Roper’s new memoir Unfollow—an eloquent, thoughtful and compelling book that not only tells her story of departure from the infamous Westboro Baptist Church, but also serves as a reminder for readers to examine their own biases towards those who hold different beliefs—even the extremists Phelps-Roper left behind.

On a few square blocks in a suburban neighborhood in Topeka, Kansas, Megan describes her family as a tight-knit universe unto itself, where—apart from picketing and ministerial activity—life was as American as apple pie. The foundation of WBC was erected on its strict adherence to Scripture, interpreted in fire and brimstone sermons by Gramps, as the family affectionately referred to their pastor, grandfather and founder of the church, Fred Phelps. From the pulpit, he’d expound in lurid details on the sexual activities of gays “anally copulating their brains out” to eight-year-old Megan, her young siblings and cousins.

She had imbibed the Biblical interpretations about God’s wrath on gays, Jews, and sinners who don’t heed his divine ordinances. Megan was fervent about the Westboro message. At thirteen, she argued Bible doctrine with strangers online. Sharp-tongued and unrelenting, she defended the church’s position in a chat room on GodHatesFags.com. She learned early on to ignore the insults they lobbed at her family—words like “hateful,” “evil,” “monsters,” “stupid”—”for the simple fact that I knew my family,” she writes. These descriptors were “diametrically opposed” to the people she knew: college-educated, lawyers, civil rights attorneys. Her family members were clever, creative and boasted flourishing careers. It was easy for her to dismiss these claims and to peg everyone outside the church as liars who cannot, under any circumstances, be trusted.

This was, of course, how Gramps kept his followers in lockstep. Building walls of distrust and filling seas of fear, he managed to tie the family—and church—together in a bind that could not be untethered.

For Megan, as for myself, the aha! moments happened because of small, banal rebellions that we believed we could contain.

She was an earnest girl. A good girl. An inveterate people pleaser. Her grandfather’s darling.

Fed with a steady stream of hate by the very people she adored, her family, Megan could not conceive of questioning the core tenets of this fringe religious group. The silent moments of doubt were always overshadowed by an overwhelming certainty that Gramps’s teachings were the word of God.

For Megan, as for myself, the aha! moments happened because of small, banal rebellions that we adamantly believed we could contain. For Megan, it started with interactions on Twitter. As Westboro’s designated Twitter spokesperson, Megan was tasked with defending the church. Jews, gay people, and random Twitter users engaged with her, dismantling the Westboro ideas and forcing her to reexamine the truthfulness of its doctrines. One of those tweeters was an anonymous man named C.G., whom she later married. Their messages, at first seemingly harmless but plainly intimate, helped lead to her ultimate unraveling. They went from debating on Twitter to daily affectionate banter on Words With Friends.

Unlike Megan’s church, my community of birth maintains its isolation from the modern world, crossing over for business and politics—but rarely for entertainment. How else do you keep the youth from being influenced by an enticing world of freedoms? As the number of defectors increases, leaders cobble together plans to stop the hemorrhage, tightening their control. Cracks are beginning to appear now with the younger generation, and I remain hopeful that this increased porousness will effect change.

While Megan’s church mingled with seculars to save the world from itself, Kiryas Joel’s isolation stems from a fear-based philosophy of appeasement. If we are good and obey Hashem, I was taught, we will be protected from another Holocaust. We were not in the business of saving the world, only ourselves.

In Kiryas Joel, modesty is the proverbial crown of a woman’s glory—and also, oftentimes, her undoing. The grand rabbi who founded the village gave fiery speeches reminiscent of Pastor Phelps about the hell that lies in wait in this life and in the afterlife for a woman who dares to wear sheer stockings or refuses to shave her head.

In 2008, the modesty committee known as the Va’ad Hatznius, a group of middle-aged men tasked with maintaining the highest standards of modesty in the village, got wind that I was growing my own hair. Married at eighteen in an arranged marriage, I was required by Satmar Hasidic edicts to shave my head and don a wig or a turban. Our rabbi had declared this as basic a tenet as keeping Shabbat. Over the years, as the community radicalized, adherence to these stringent modesty rules morphed into something greater, trumping even the divine commandments in the Torah.

The tenth child in a dozen, I was surrounded by married siblings who either shaved or had wives who did. Questioning something so foundational to our lives would be unthinkable—and yet, after three years of baldness, I let my auburn hair grow, careful to hide every last strand with a wig or turban.

This seemingly ordinary act was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back.

I cannot tell you where I found the courage to defy this rule—or why. But, much like Megan and her online friend/foe whom her religion forbade her from knowing better (she could only marry a WBC member—and no dating, obviously), this seemingly ordinary act was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back.

“I’d already let this ungodly affection for an unbeliever take root in my heart,” Megan writes of her anguish over lusting for C.G. “If I didn’t rip it out with both hands, I would fall away and lose everything—my family, my friends, my whole life in this world—and in the world to come I’d be tormented in Hell for all of eternity, where the worm that consumes your flesh never dies and the fire is never quenched.”

And this is where Megan’s story strikes a visceral chord: I, too, felt imprisoned by an all-consuming guilt for living in sin as a married woman with hair. At the time, I’d give almost anything to reclaim my innocence and steady the rocking boat.

When I came home the evening after our meeting with the modesty committee where they threatened to expel my son if I kept my hair, I shaved it all to a stubble. I couldn’t see it at the time, but this final act of subservience would lead me to my first autonomous decision: I will never again shave my head. In that moment, facing the mirror with a shaver on my scalp–feeling naked and violated–I could not imagine leaving my community. The gut-wrenching guilt of defying this long-standing custom passed down for generations was too big a burden to carry.

I risked harming my children with unimaginable ills. I could lose my joy in the here and now and in the hereafter. Indoctrination is so powerful, its undoing is like splitting a sea.

These feelings tore at my conscience. How do I stand up to what I know deep in my core is wrong while honoring the dearest people—my mother, sisters, family and friends—who will likely take this rejection personally? These emotions still simmer in the background of the life I’ve built. How do I tell my story while exhibiting compassion for my former community members?

It is apparent how much Megan loves her family—especially her mother and father, still. Her compassion for those she’s left behind is truly breathtaking. “I had lived to support them. There was no worse anguish than causing them pain,” Megan writes, a sentiment that reminds me of my own mother’s pain watching her daughter veer from the beaten path.

The reason fundamentalist communities have so many restrictions is because almost any act of defiance could be the first crack in the facade.

By sheer will—and through the help of her Twitter debaters—Megan leaves the church and dives head-first into a void. She describes feeling “physically ill” at her initial encounter with secular culture. She imagines God smiting her as she drives away, sending her car careening off the highway.

It’d be easy to dismiss the followers of WBC as maniacal extremists. But reading Megan’s account, I was struck by her gentle words. (Though I recognize that her words would certainly not be gentle had she stayed or continued to toe the party line.) And this is perhaps why I felt a strong kinship with Megan when we first connected last summer. Megan, Yasmine Mohammed—an ex-Muslim activist—and I had prepared for a speaking tour on fundamentalism. The tour fell through, but in the process, I formed a friendship with these women. Megan’s deep and eternal love for her family resonated with me then—and even more so after reading her book. While my family has not abandoned me, our relationships suffered as a result of my departure. Yet I love them dearly—especially my mother, whose stoicism reminds me of Megan’s mother.

For Megan to tell her story with love for the people who excommunicated her is remarkable not only because it reflects an emotional maturity, but also—and most crucially—it disproves the fearmongering WBC relies on to prevent this kind of erosion: namely, that outsiders are not to be trusted.

While every expat steps onto the path of defection by different means, it is rarely a single episode or aha! moment that serves as a catalyst for change; almost anything could trigger the pendulum to swing. The takeaway from Megan’s story—to me anyway—is that the reason fundamentalist communities have so many restrictions, some of which would seem downright petty to outsiders, is because almost any act of defiance could be the first crack in the facade.

Before you go: Electric Literature is campaigning to reach 1,000 members by 2020, and you can help us meet that goal. Having 1,000 members would allow Electric Literature to always pay writers on time (without worrying about overdrafting our bank accounts), improve benefits for staff members, pay off credit card debt, and stop relying on Amazon affiliate links. Members also get store discounts and year-round submissions. If we are going to survive long-term, we need to think long-term. Please support the future of Electric Literature by joining as a member today!