Reading Lists

7 Books About the Heartbreak of Losing a Sibling

Willa C. Richards, author of "The Comfort of Monsters," on one of the closest and most complex family bonds

Perhaps one of the more bizarre aspects of having siblings is the sense that this person, your sister or brother, could have been you. Some other combination of the same genetic material has produced this person, who sometimes seems almost like a shadow self or an other-worldly version of yourself. It’s like seeing alternate versions of the way you turned out. Variations on a theme. This can be interesting, but it can also be horrifying.

Because I grew up in such a large family, I’ve always been attuned to, and interested in, the effects our relationships with our siblings can have on us. I’m particularly interested in the deep intimacy that can result, especially, but not exclusively, between sisters, and the ways this intimacy can corrode, reform, even completely disappear, over a lifetime.

In my debut novel, The Comfort of Monsters, the protagonist Peg McBride loses her younger sister. Because they were exceptionally close as girls, and because Peg was, ostensibly, the last person to have seen her alive, she carries a deep sense of guilt and shame about her sister’s disappearance.

In writing my book, I looked to literature that explored these complicated connections and what happens when they are broken: when a sibling dies, disappears, or flees. Below are seven books that showcase the specific horror and heartbreak of loving and losing a sibling:

Long Bright River by Liz Moore

With a heart-racing plot and a gorgeously flawed, yet painfully perceptive, narrator, Moore’s novel tackles a heady set of subjects: intergenerational trauma, addiction, sex work, police misconduct, single motherhood, and sisterhood. Set mostly in the Kensington neighborhood of Philly, Long Bright River follows Mickey Fitzpatrick, a beat cop, who undertakes a desperate and at times ill-informed mission to find her missing and long-time heroin-addicted sister. Mickey mines her past as much as her present to understand how both she and her sister ended up in the novel’s present moment. Her search for her sister is set against a disturbing slew of femicides, and like the narrator herself, readers are holding their breath every time another victim is discovered. A beautiful, wrenching book about the ties that bind us and break us.

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson

In Housekeeping, a pair of sisters, Ruthie and Lucille, work through the wreckage of their mother’s suicide at the not-always-so-steady hands of their aunt Sylvie. Though the sisters were once close, spending days skipping school and playing in the woods, eventually Lucille feels the tug of proper society. And one day—fed up with her aunt’s eccentric habits and poor housekeeping, and desperate to belong and live a “normal” life—Lucille abandons her sister Ruthie and goes to live with her schoolteacher. Lucille’s desertion ripples through the novel, haunting Ruthie, and readers until the very last sentence. A deeply empathetic and moving portrait of the sometimes irreparable ways we so often grow apart from those we love.

Caucasia by Danzy Senna

The pulsing heart of Danzy Senna’s debut novel is the narrator Birdie Lee’s love for her older sister Cole, which is a beautiful but complicated kind of love. The sisters’ mother is white and their father is Black, and though the girls are so close they share a secret language, in public people often don’t believe they are sisters. Birdie is so light-skinned that people sometimes mistake her for white. When their parents decide to split up, supposedly to protect their mother who believes the FBI is after her, Birdie’s life is changed forever.

Birdie and her mother run away; Birdie is forced to become Jesse Goldman and to pass as a white girl, because her mother says that the FBI will be looking for a white woman with two Black daughters, not a white woman with one white daughter. Birdie lives several years on the run, pretending to be Jesse, and the consequences of her mother’s lies are devastating. All the while, Birdie yearns for Cole, for their secret shared language, for the sense of self she used to find reflected in Cole’s face, for her father, and for wholeness. Eventually, she leaves her mother and sets out to find the other half of her family. Caucasia is a fast-paced, heart-breaking, and whip-smart read about the deeply constructed nature of race and the very real harm these constructions inflict.

The Unpassing by Chia-Chia Lin

In this debut novel, set against the bleak backdrop of the Alaskan wilderness, Chia-Chia Lin portrays a Taiwanese immigrant family of six as they try to make a new home in a beautiful but nearly inhospitable place. Tragedy strikes the family when several of the children contract meningitis. The narrator, Gavin, is so sick that he is unconscious for a spell. When he awakes, he finds out that his sister Ruby has died. Gavin grapples with his grief throughout the novel, believing himself partially responsible for passing the sickness onto Ruby, and thus for her death. Ruby’s death haunts the whole novel’s telling, and remains a powerful vacuum of grief, like a large black hole, that the family struggles not to fall into. The Unpassing is an empathetic, deeply felt, and lyrical portrait of childhood loss, of never-ending grief, and of unbearable unbelonging.

A Home at The End of the World by Michael Cunningham

The narrator, Bobby, adores and even idolizes his 16-year-old brother Carlton. And when Carlton renames his little brother—christening him Frisco—he turns him into a “criminally advanced nine-year-old”. Bobby yearns to live up to his brother’s opinions of him, so he tags along on a number of adult exploits, including taking acid with his breakfast cereal, following his brother to a cemetery where he spies on him having sex with his girlfriend, and attending their parents’ boozy house parties. The narrator doesn’t just want to grow up to be like his older brother, he wants to be his older brother. But Carlton’s death, at the hands of a shocking accident, alters both Bobby’s and his parents’ lives forever. And though the remainder of the novel takes readers far from the moment of Carlton’s unexpected death, to—as the title suggests—“the end of the world,” the magnitude of this loss continues to haunt Bobby into adulthood.

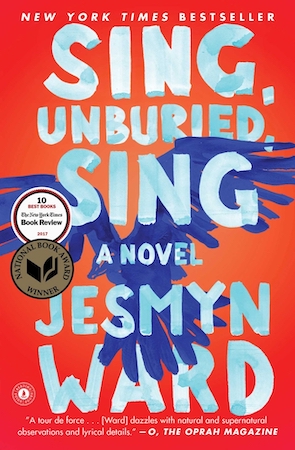

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward

Jesmyn Ward’s novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing, is the story of Jo-Jo, a 13-year-old boy who is struggling to navigate his fraught familial dynamics. His father, Michael, who is white, is in prison at the infamous Parchman penitentiary and his mother, Leonie, who is Black, is an on-again-off-again drug user. And so the care of his little sister Kayla often falls to young Jo-Jo, and they form an intense, survivalist bond that Ward portrays with heart-wrenching tenderness. Haunting, and complicating these dynamics, is the ghost of Jo-Jo’s uncle, Given, who was the victim of a suspicious, likely racially motivated, shooting accident. Leonie is perhaps most affected by the loss of her brother Given and harbors wrenching guilt both about his death and her relationship with Jo-Jo’s father, Michael, who we later learn is related to Given’s killer. Leonie is deeply jealous of Jo-Jo and Kayla, because their closeness reminds her of her own loss. Though the meat of the book centers on Jo-Jo’s fraught relationship with his mother, who is spiraling out of control throughout the novel, Given’s absence affects the entire family. A powerful, lyrical exploration of the ways that violent loss and systemic racism have ripple effects through generations.

Nox by Anne Carson

Nox—a difficult-to-categorize, shape-shifting sort of book—is required reading on grief. It’s a notebook of memories, including letters, poems, photographs, collages, paintings, and other fragmented artifacts compiled after learning of her estranged brother’s death overseas. Equipped only with one letter from her brother Michael, a handful of phone conversations with him over the years, and a limited knowledge of his movements, Carson struggles to write “an account [of his life and death] that makes sense.” And in some ways, though these investigations begin to sketch out a story for Michael, ultimately the assembled fragments are too inscrutable to become anything beyond that—a sketch, a kind of bizarre constellation of answers to all of Carson’s questions. A one-of-a-kind exploration of the circular processes of grieving, especially for a brother, a sibling, a person you feel you never really knew.