Interviews

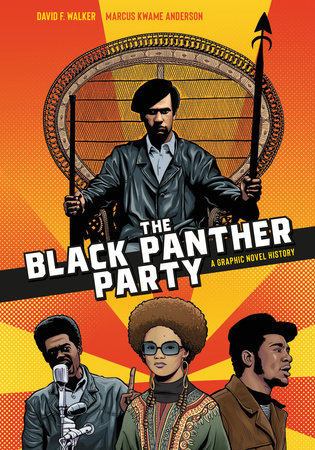

A New Graphic Novel Shows the History of the Black Panther Party

Even those who know about the movement will learn something new—and see how the past repeats itself

David F. Walker and Marcus Kwame Anderson’s graphic novel The Black Panther Party may be the first introduction to the revolutionary party for some. For others, it will provide additional context to the history. The graphic novel spans from the founding of the party by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale in the mid-’60s to its unfortunate demise when members were murdered, ostracized, or imprisoned. It covers the constant government attacks to the Party—cue J. Edgar Hoover, who stated the Black Panthers were the “greatest threat to the internal security of the country”—and its internal strife, against a background of increased racial tensions throughout the nation.

Walker and Anderson’s collaboration reveals that the Black Panthers weren’t without faults, yet the organization’s focus from the beginning was always giving Black communities the strength and power to be informed of and fight for the rights they deserved. From food pantries to educational programs to a newspaper circulating relevant and under-reported news affecting Black people, the Black Panthers served their community first, which seemed radical to those who never thought Black people deserved basic rights in the first place.

I spoke with the author and illustrator about the challenges of bringing forth more rounded information about the Black Panther Party, and the cyclical ways social justice movements have fought not only for our voices to be heard but for survival.

Jennifer Baker: David, in the afterword you spoke pretty poignantly about having conflicted feelings about writing a book about the Black Panthers. What was your approach in regards to this graphic novel? Did you and Marcus think about what existed already or did you primarily think about what you wanted to do?

David F. Walker: I went arrogantly into it thinking “I know a lot.” Thinking this would be easy. And that was my first mistake because I didn’t know as much as I thought I did. When I went into it [it was] with the attitude that this book would be for people who knew nothing about the Panthers. I didn’t dumb it down in any capacity, [but] I felt like if you never heard of the Panthers or if all you know is the name or had seen an image or know about Bobby and Huey, that this would be sort of the Panthers 101 History as a great jumping off point. And even then it was still a challenge—despite what seems like a lot of material out there, there’s not really as much as you would think, and some of it is sort of one-sided and at times even unreliable in its information. It was definitely a big challenge, and I think that also for myself there were definitely people in the Party who I didn’t have as much of an understanding of, [and] I began to understand them more. And at times [this] was conflicting because these were actual people. We learn about them as iconic figures, but they were people who made some really great decisions and some not so good decisions.

Marcus Kwame Anderson: Not dissimilar to what David was talking about, I was going in with a good amount of knowledge. I came up in the ’80s and the ’90s and I remember “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” [by] Public Enemy, there was just all kinds of Panther references. And I remember them talking about being a supporter of [JoAnn] Chesimard (Assata Shakur). So it was at that time when I was in high school in the ’90s where it sprouted the interest to learn more. But like what David was saying, no matter what you know there is so much more, so I was coming in with information but David is very humble about what he does. When I was reading the script I was impressed with how much he did get in there and how much of a big picture it gives. I was excited, and for me it was a very huge task but also felt like a task that I was kind of meant to do, just in the sense that my interest in work that deals with the African diaspora and social commentary and all that and my love of comics, they really merged on this project in a way even before I knew about this project.

JB: Marcus, can you talk a little bit about your artistic approach? There’s a softer element to your work. There’s not as many hard edges and there’s a great attention to hues and how they balance out on the page.

I grew up reading comics back in the ’80s, ’70s, and before, and there was one brown for Black people, period. I’ve never gone to a default brown.

MKA: I always try to draw what I want to read. When I read comics I’m a fan of people that are inventive when it comes to page layout and panels. One of the things you’ll see if you read the book is oftentimes I’ll break the panels with borders, not necessarily just to do it, there’s always a reason for that. I grew up reading comics back in the ’80s, ’70s, and before, and there was one brown for Black people, period. I’ve never gone to a default brown, so I would look at it like Huey’s complexion is darker than Bobby’s. And then you have Angela has her complexion so I tried to really be true to that. One of the challenges is I was working from a lot of black and white reference images. But for a lot people who are still around I was able to find some color images for color references. And David and I had also talked about coming up with simpler color palette and some colors that could be found in the Panthers’ newspaper because the newspaper was a huge part of the Party and the design was very dynamic. A big part of the color theme was orange and blue, that’s my favorite complementary color combination, so I kind of built a lot of the color around that. But then you’ll see there are pages where the murder of Fred Hampton, scenes that depict racist violence, are in more red hues and that was a very deliberate choice. But for a lot of the scenes that were less violent I went with some softer colors like you were talking about.

JB: I also want to get into the women that are featured. I haven’t amassed as much Black Panther history myself, but there’s a lot that was revealed to me. Because of how information was unraveled I had a deep appreciation for seeing women like Erika, Kathleen Cleaver, and Tarika Lewis actually discussed.

The leadership roles were primarily men, but the Party lasted as long as it did because of women.

DFW: Thank you for bringing that up, because I honestly feel like if there’s one part of the book where I fell short it’s this particular part. I actually wanted there to be more about the role of women and specific women in the Party. When I went into this [I was] thinking “I know all about the Panthers, this is gonna be easy,” but then the more research I did it seemed like it was impossible. It really felt like women were written out of the history. And I really had to dig deep to find stuff. In some cases I had to talk to people who were in the Party to get a feel for it. Elaine Brown’s memoir, her autobiography, is probably one of the key publications that deals with women in the Party, but that’s only one person’s story. Kathleen Cleaver has yet to produce anything along those lines and Angela Davis, she doesn’t talk as much about the Panthers. And I was getting really really frustrated and I was committed to having something in the book.

It was one of the last sections of the book that I finished writing because I was still conducting the research. And I think more than anything else, where I talk about the stuff that I learned and how incomplete the history of the Party, the women and the role that they played is the thing that stands out in my mind the most. And I feel like that definitive book has yet to be written. That story has to be told, because when you look at the numbers more than half of the party was made of women, rank and file women. The leadership roles were primarily men, but the Party lasted as long as it did, it survived and did all that it was able to do because of women. I don’t know that it would be me [to write it] but it really needs to be about the complexity of gender, gender identity, and what women have to do just to survive. And not just survive but get acknowledged for the work that they’re doing.

JB: You’re right that there’s such a dearth of Black women in our history books and in their connection to the Party. Even your intro of Civil Rights and reading more books, I’ve learned how PR driven some movements were.

DFW: When I look at … history or Black history, the role of women—I didn’t realize this ‘til I got older and began taking my work more seriously—I didn’t realize how much the role of women was diminished. And now that I see it I’m more aware of it all the time. To the extent that I feel like okay, as I move forward in my career and my life, one of my life battles has to be to help level that playing field and to help find opportunities for creators who might not get the break that they need and for stories to be told that might not have been told.

I would love for people to start talking to their families and recording their stories. That’s how we’re going to understand the Party.

I remember reading just a paragraph of how Tarika was the first woman to join the Party, and Marcus can talk about this too, figuring out what she looked like was so hard. ‘Cause there were pictures of her, but there’s only three or four and none of them were labeled correctly. And so it took forever. There are several women who I have pictures of. There’s one woman whose name escapes me at the moment. But I had 30 or 40 pictures of her with her name and there were enough pictures that I thought “Okay, she had to be somebody if someone took this many pictures of her.” But I couldn’t find her name in a single book. In the back of my mind, I’m thinking, “There’s the story here.” I want to know her story. She has this dynamic look about her. There’s pictures of her in the newspaper and a couple other photo essays but nobody took time to write about her. And that to me, when we talk about the Panthers and when we talk about people in general, the rank and file, that’s where the true story of the Panthers is. Some of those rank and file members are still with us, they’re our parents or grandparents, our aunts and uncles. I would love for people to start talking to their families and recording their stories. That’s how we’re going to understand the Party, what they went through and how to learn from what they went through.

MKA: What David mentioned with Tarika Lewis is really important. Because … there were more recent pictures of her when I was researching her, so I found myself really trying to cross reference her pictures with older pictures to try and de-age her. But it really was a challenge. Speaking to David’s earlier point of the importance of someone following this work, I’m just thinking about the fact that a lot of the people in the Party and the people we’re speaking about aren’t here, and the people who are right now I do think it’s important for as much of their story to be told both in our book and otherwise, because they’re not going to be around forever. And I don’t want some of the lesser known aspects of the history, especially about the rank and file people, to be lost.

JB: With this contribution to literature about the Black Panther Party, is there a conversation you want us to engage in or dissect a bit more when it comes to social justice parties and grassroots work for us and by us?

Look at what happened to the Panthers, and know that those same tactics are being used against you right now.

DFW: There was a moment when I was working on the book where I realized that the age that I am right now, right this very minute I am old enough to be the father of any founding member of the Panthers. Bobby was the oldest when he formed the party, I think he was 25, 26. Bobby Hutton was only 16. Huey was in his early 20s, and there were moments when I was reading about what they did and things that happened to them and I realized I was reading it from a middle age man’s point of view, where I don’t have the same fire in my belly that I had in my early 20s and my late teens. And what I was thinking about was, how do we keep that fire in our bellies, the thing that drives us the way it drove the Panthers? How do we keep that going as we get to middle age and how do we survive long enough to do something with it? One of the worst tragedies of the Panthers is that all the people who were killed, most of them were killed before they hit 30 years old. And when Huey died he was in his 40s, but he might as well have been in his 80s in terms of all the things he’d been through. And so it was just really interesting to me because I thought about what would it take for me now as a man in his 50s to take arms? And more importantly, what would I say right now today to young people? I look at what’s going on with the BLM movement and I see people out in the streets and there’s part of me that’s like, “Maybe I should go out there with them, but I got a bad back. And I don’t want to fall and break a hip.” I really would like to see more people my age think about how we can help educate and mentor young people. But I would like young people to look too, as they wonder why nothing has changed in their mind, look at why it hasn’t changed. Look at what’s happening. Look at what happened to the Panthers, understand how they were infiltrated, how they were turned against each other. And know that those same tactics are being used against you right now.

MKA: When I started working on the illustrations it was last spring or summer of 2019, so this is pre-George Floyd but post many other travesties of justice. And as I’m reading about these things all these uprisings that happened in history into the 20th century, some of them you could’ve just changed the names and it would’ve been any headline that we could speak of in the last ten years. Then the tail end of my work directly overlapped with the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, so those uprisings were fresh in my mind. There was a surreal moment this past May where you would see a lot of people who had previously been very uncomfortable with the phrase or idea of BLM becoming more comfortable, and all these companies getting their graphic designers to put statements about. And I don’t want to make light of it too much because I think even incremental progress for people, the idea of BLM being less vilified is positive. But I felt reinvigorated living with the Panthers for a year. I had read about them and learned about them, but to create this book I felt like I was living with them this past year and it really did help reignite a fire within me. I also think it’s important for this story to be out there so it can inspire people, but they can also learn from the ways it didn’t work. I really think that’s what progress is. We stand on the shoulders of others and you take inspiration from the things that worked and then you try to rebuild from the things that didn’t.