Interviews

How the Trauma of Racial Violence Stays in a Family for Generations

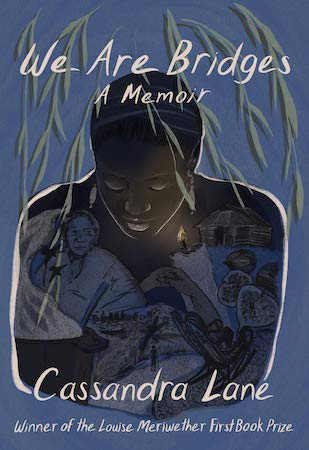

Cassandra Lane's memoir "We Are Bridges" explores the legacy of lynching and why we can't simply let go of the past

As a country, we seem far from acknowledging that slavery and racial violence have consequences in present-day for living Black Americans. Despite new focus on long-term material and psychological costs of slavery and its aftermath, for most Americans, lynching exists in a Coen Brothers movie or a middle-school history class. But lynchings lasted well into the 20th century. For some Americans, it is tangible family history.

Cassandra Lane grew up knowing her great-grandfather, Burt Bridges, was lynched. When she found herself pregnant, she began to research family history for the sake of her son. Her debut memoir We Are Bridges shuttles between contemporary Los Angeles and the South, recounting the grief and terror experienced by survivors and reclaiming family history from violent erasure.

Winner of the Louise Merriweather First Book Prize—praised by Jericho Brown as “a love story, a book of how,” by Dana Johnson as “a blazing kaleidoscope of legacy and memory”—We Are Bridges explores how lynching ended the life of Burt Bridges and changed the lives of his widow, child, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, who survived in a haunted border between silence and whispered fact. An exploration of both national and personal history, this book insists that enduring is a fervent wish, the only option, and a heavy burden.

Debra Monroe: Cassandra, tell us how did you first begin thinking about this book.

Cassandra Lane: Years ago, I set out to center this book on my great-grandfather, Burt Bridges, because I became obsessed with the fact that this kind of racial violence had happened so close to my generation. As a kid, I would sit and watch my grandfather crying about his “real daddy,” and it baffled me, but I see now that trauma that happened to his father was something I could have touched simply by touching his skin, or hearing him in a deeper way.

DM: And yet in the final version, the most compelling threads of the story are the lives of the female descendants. What did you discover about Black women’s lives?

CL: Yes, while his pain and loss were the impetus, it was the women—my grandmother, my great-grandmother, and my mother—who started popping up in, first, small ways, and as I continued to write, as the focus. I felt I knew them so well. Their working and cleaning and child-rearing. Their romantic pain and disappointments—all that I wanted to be free from. But what I hadn’t considered was their strength, their survival, and their creativity for survival.

DM: Psychologists have posited the idea of intergenerational trauma—that hypervigilance our ancestors cultivated—is, for us, learned, reflexive. Recently, epigenetic studies have found that parental trauma leaves a mark on genes. Can you talk about this research?

CL: It was already something many of us sensed when we thought about ills in our families. We’ve all talked about family “cycles.” Growing up in a deeply religious family, I remember being fascinated by that scripture that talks about the sins of the father and considering all the “begats” and how histories connect. An emotional breakdown I had over race while on a visit to a nightclub in NYC when I was in my 20s caused me to want to examine the rage I felt inside. It felt ancient. I knew it was bigger than that moment. When I saw my first article about epigenetics, it felt so affirming.

DM: In what way?

CL: In a I’m-not-crazy way. It connected me to the pain of my ancestors, but also to their resilience. It was more eye-opening when I worked for a time for an early education nonprofit and learned about ACES.

DM: ACES, or Adverse Childhood Experiences, which makes people more likely to develop depression, risk-taking behavior, even reduced life expectancy. Right?

CL: Yes. Learning how we carry invisible baggage was freeing. Biology mirrors the emotional experiences. Science gives it a why.

DM: I think Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns is important because many people know about American slavery but little about the decades after, when thousands of Black Americans were lynched or fled the South to escape lynching. White people tend to draw a line under 300 years of slavery in 1865—done, over. Wilkerson’s book is about slavery’s aftermath, Jim Crow. Your book is about Jim Crow’s aftermath. If there’s one insight about your book you hope readers take away, what is it?

When I started writing about my family’s lynching story, it seemed that so many had moved on from these issues, because so many Black families physically moved.

CL: The Warmth of Other Suns is brilliant, revelatory. I only wish I’d had a book like it when I was growing up, when I was in college and, later trying to find my way in the world as a young Black woman newspaper journalist. My family was one of the ones that stayed. For the most part, they did not migrate to the West or North. I moved out of Louisiana for the first time when I turned 30, a kind of modern-day migration. When I started writing about my family’s lynching story in the early 2000s, it seemed that so many had moved on from these issues, because so many Black families physically moved. I remember a young white writer coming up to me after a reading in our MFA program. Her eyes were wide and full of something I couldn’t quite name. “That couldn’t have happened to your great-grandfather,” she said. “I had family in the South. I can’t believe it.”

DM: What did you say?

CL: I wanted to say, “I wish I were making it up, but I’m not!” I was taken aback by her shock. We were part of a group of writers and artists getting to know each other through literary events and hanging out, laughing it up, sharing our hopes and dreams. Little did they know I was harboring this past. But artmaking is going beyond the surface of what is pleasant and comfortable and bringing it to light, crafting it to present as connection and conversation. I turned that lens on my family, and that made that friend uncomfortable. There was a Filipino friend, too, and I know Black people who say: we’re more than that now. And throw around phrases like “pain porn” and “struggle porn.” More silencing.

But we carry this baggage. People feel a safe distance looking at slavery artifacts in a museum or watching a film about slavery. But when you think about blood that was shed in the 20th century, we’re not talking about ancestors we cannot name. We’re talking about living, breathing people. My mother and grandmother. Other people’s mothers and grandmothers. My mother was born in 1953 and never attended a school that was not segregated. When my family gets together, we have in the same room someone who couldn’t drink from a white-designated water fountain, and my brothers who are in their 30s and were some of the only Black kids in their suburban schools. When you go back one generation beyond my mother’s, there is my grandfather, who never met his father because his father was lynched. As a kid growing up in the 70s and 80s, I was fascinated and repelled by his pain. I was nursing my own absent-father wound. I’d think: why hasn’t this old man gotten over this?

DM: It takes a big cognitive shift to get past our experience and understand someone else’s.

When you think about blood that was shed in the 20th century, we’re not talking about ancestors we cannot name. We’re talking about living, breathing people.

CL: Yes, and as a culture, we’re like I was back then: Why can’t they/you/we get over the past? This question is asked a lot about Black stories. But you can’t without acknowledgement, reparations. What I think my papa wanted was for someone to listen. This book is my reparation—an offering to my ancestors. In attempting to listen to my grandfather, to each of my elders, I started hearing myself. I then cleared a passageway to listen to my unborn child. And to other people’s children. I hope never to silence or shame anyone. My great-grandfather was lynched, Grandma Mary said, because the white folks thought he was too “sedity” or “uppity.” When I think about how a lynched person is cut off at the throat, the vocal chords, I think the murderer is intentionally squeezing the life out of that vessel of expression. He had a right to live, to not be silenced. The implication in telling Black writers to get over the past because there’s some exploitive or sensational form of pleasure in pain couldn’t be farther from the truth.

My grandmother used to say: “I pray for my children and my children’s children and my children’s children—that none of these evil things come in their day.” What we call evil keeps coming, but we keep praying. And writing. Highlighting what’s wrong—in us and around us.

DM: You feel tacit pressure to stay affirmative in a phony way.

CL: Yes. But writing about my great-grandfather’s lynching doesn’t take away from #BlackBoyJoy or even my own #BlackGirlMagic. In considering Burt Bridges as a flesh-and-blood human being, I found a young man full of hopes and dreams as well as a murder victim. I tapped into his joy and desires and my own. The full spectrum is sometimes light, sometimes heavy.

DM: You’ve been immersed in your family’s darkest history a long time. Did you ever feel an estrangement from the present that seemed like too big a risk?

CL: The first thing that comes to mind is a conversation I had with my mom. She never seemed too thrilled that I was obsessed with Burt Bridges. I remember her gently egging me to write about her mother’s side of the family. I was taken aback. “That’s not the story I’m trying to tell right now,” I said. She wanted to leave the past in the past, perhaps. I wondered, “Should I?” But my ancestor’s tragedy led me to understand my issues. Eventually, the story became about so much more than Burt. Motherhood—mine with my son, my mother’s with me—became a counterweight to the heaviest parts of the story.

DM: Do you feel any closure after years of exploring this subject?

This question of ‘why can’t they/you/we get over the past?’ is asked a lot about Black stories. But you can’t without acknowledgement, reparations.

CL: I had to narrate the book to record it as an audio-book. I had to read it aloud in front of strangers start-to-finish, with all the feelings that came with that process. It was hard. It was also cleansing. I still plan on seeing a therapist again, just to work with me through the process of bringing this long-held story out into the public. I don’t believe anyone is ever completely healed.

DM: Can you describe how you could tell when you were on the right track, following your instincts to tell this family history?

CL: Debra, those old Southern women who raised me went so much on whether things were “sitting right.” Today, we call that “energy” or “vibes.” I grew up in a household where there was always talk of visions and prophetic dreams and sightings of ghosts and spirits, so there is nothing strange about those other worlds to me. We were also surrounded by nature—trees of all kind, nearby woods, and all the sounds that come from the woods—so I get quiet and listen for all of that even in my super urban neighborhood in Los Angeles. I am always listening for sounds of the past.

DM: It’s not much of a leap to say that violence inflicted on Black men’s bodies a century ago has evolved into violence against Black Americans today. We still don’t talk about survivors. They appear in news stories as the person who recorded the video, the person telling us what happened. Has your understanding of survivors changed?

CL: The survivors! It was one thing to relive the lynching of Burt, but once I turned my lens onto Mary, I began to wonder what the day of lynching was like for her. Was she a witness? Did she find out later? Yet Mary went on to live for another eight decades. She farmed. She raised Burt’s child. She fed people who were poorer than she was. She repressed what happened by not talking about it, and yet when she was on her deathbed in her 90s, she reminisced and wept about his beauty and his spirit and how much she loved him. We talk about how strong Black women are, and that trope can be too much. We should not have to carry the weight and make it look easy. I admire survivors, but what more can we do as a nation, as communities, to give survivors what they need? Back then, there was faith, the church family, but not the kind of psychological supports that encouraged talking about trauma. What I learned about the survivors is the damage that silence inflicts on a person, a family. We need to tell more survivor stories. We do.