Books & Culture

Shirley Jackson Predicted America’s Fetishization of the Murderess

How did she know we’d still be talking about Lizzie Borden?

My great-grandmother grew up in Fall River, Massachusetts, the home of the still-infamous murders of Andrew and Abby Borden. She was privy to the trials, the rumors, and the thrills long before the Christina Ricci Lifetime adaptations. She passed the tale of Lizzie Borden — because it is, in numerous ways, a “tale” — along to my grandmother, who then told it to my mother, and then to me.

I spent much of my childhood reciting “Lizzie Borden took an axe / gave her mother forty whacks/ when she saw what she had done / she gave her father forty-one” like I would any other of Mother Goose’s nursery rhymes (and fittingly so, as this more gruesome rhyme is rumored to have been written by Goose herself). The macabre and the grotesque were celebrated and normalized in my house. In elementary school, I dressed as American McGee’s Alice for the Halloween parade, brandishing a plastic machete that spurted fake blood onto my sky blue, Disney-licensed dress. In high school, we visited the boxy green house of the Borden murders as a family; we sat on the davenport with a black and white photo of Andrew Borden’s sunken skull above us, we visited the gift shop, we left with dolls.

I have always felt that by celebrating all that is strange, I was simply celebrating my own strangeness. And this may still be true. But by doing so, I may have also contributed to the very sensationalism that demonizes and others strange girls, and it took several Shirley Jackson novels for me to finally figure that out.

I needed to cover my eyes, but I wanted, so badly, to peek through my fingers. I loved this fear strangely and too much.

As a teen, I was naturally assigned “The Lottery” for Honors English I. The strange, suspenseful horror of the story terrified and enthralled me all at once — a feeling new to me, but one that has always been exploited and preyed upon. I needed to cover my eyes, but I wanted so badly to peek through my fingers. I loved this fear. I loved it strangely and too much.

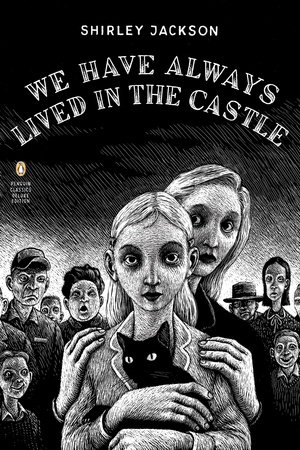

So I moved quickly through Shirley Jackson’s entire bibliography, beginning with We Have Always Lived in the Castle. It was here, on about page five, that I scrawled “LIZZIE BORDEN?!” in all capital letters, thrilled to find two of my favorite fascinations merging.

Jackson, an odd and oppressed woman herself, explores the sexist and classist implications of the Lizzie Borden trials in Castle, via the thinly-masked Blackwood family. However, she also takes the analysis of the murders and Borden herself a step further by interweaving deconstructed fantasy elements with this realistic, and even arguably historical fiction. Merricat and Constance Blackwood are mostly estranged from their New England village after Constance is acquitted of the murders of her parents and younger brother. Yet her acquittal does not quell the constant taunts of children:

I wondered if their parents taught them, Jim Donell and Dunham and dirty Harris leading regular drills of their children, teaching them with loving care, making sure they pitched their voices right; how else could so many children learn so thoroughly?

Merricat, said Connie, would you like a cup of tea?

On no, said Merricat, you’ll poison me.

Merricat, said Connie, would you like to go to sleep?

Down in the boneyard ten feet deep!

This reveals the initial paradox of both the Blackwood and Borden trials: both Lizzie and Constance were found innocent despite incriminating evidence (Lizzie’s dress burning and hatchet dismantling and Constance’s rapid rinsing of an arsenic-filled sugar bowl). They were acquitted quickly after each jury had difficulty believing a woman could act so cruelly. However, after the trials, the supposition that femininity is synonymous with altruism and docility did not hold up. Both Constance and Lizzie experienced harassment far more unbearable than a jump rope rhyme, causing the former to suffer agoraphobia and the latter to relocate altogether.

Neither woman was treated as human, in either their arrests or their acquittal; they were treated as spectacles. In each situation, the police and councils neglected to consider the full spectrum of evidence which would have effectively solved the crime one way or another (it was Merricat, after all, who murdered the family, but she was never even suspected, mostly likely because she was only a little girl). The concern did not lie with the murder, but instead with the murderess, a construct treated similarly to that of a deconstructed maiden or princess. The construct of the murderess has almost nothing to do with culpability. It’s a concept begotten from circumstance, and perpetuated as a fetish. The murderess is always strange, always unconventionally beautiful (or perhaps made pretty only as a murderess), and always, always sexualized. She is not a woman, but a thing.

They were acquitted quickly after each jury had difficulty believing a woman could act so cruelly.

Constance and Lizzie were sentenced to their respective towers, or castles as Jackson aptly asserts in her title. They are indefinitely arrested and subjected to endless conjecture and voyeurism. They are not their own, but they are the objects of the village — objects of Americana. Their homes will be burned down or slept in forever, and in many ways, so will their names.

To this day, Lizzie Borden’s culpability in her family’s murders is completely unknown. With the distance of time, it becomes increasingly difficult to separate the facts of the event from the torrent of rumors that followed, yet the language surrounding the event always points to Lizzie Borden (i.e. Lizzie Borden murders/Lizzie Borden Bed & Breakfast, etc.)

The murderess is always strange, always unconventionally beautiful, and always, always sexualized. She is not a woman, but a thing.

This rhetoric surrounding female culpability has persisted in American media. How many, for example, can even name the victims in what journalism has referred to as the Amanda Knox or Casey Anthony murders? Both women were acquitted of homicide. In Knox’s case, the actual murderer of Meredith Kercher has been identified. Yet, tabloids, Lifetime adaptations, and Freeform dramas still abound, all plastering the names of these women, forever associating them with a crime from which they have been exonerated.

In the words of Nick Pisa, the slimy journalist who coined the offensive, yet ubiquitous phrase “Foxy Knoxy,” this is because in American media sex sells. A woman, specifically a murderess, is a spectacle, and America has always loved a circus. Elizabeth Yuko’s 2016 Rolling Stone article, “Lizzie Borden: Why a 19th Century Axe Murderer still Fascinates Us” posits:

The salacious elements and the uncertainty surrounding the Borden murders has become modern American mythology. In addition to the fact that the only real suspect was acquitted and the case was never solved, the murder and trial occurred during a time when the quantity, quality and content of American newspapers was changing rapidly.

Once the arrest has been made, the woman is no longer an individual, but instead a product of that mythology. She is the strange, misunderstood girl that society projects Peter Pan syndrome upon — she does not grow older, uglier, or wiser. She must be the maiden wolf in sheep’s clothing forever: fantasizing about adulthood; removing controlling parents à la Freud’s family romance; and of course virginal, yet motivated subconsciously by sex.

This is why Jackson’s Merricat is doomed to the twelve-year-old mindset forever—burying dolls, begging for desserts, and practicing sympathetic magic into her adulthood. Likewise, Lizzie will always be an unmarried girl of 32 carefully feeding her pigeons, despite the fact that she lived to be 66. That is how the media views the murderess: stultified in their youth and stuck in the infantile mentality of the forever assumed murder.

And Jackson was well before her time in her implications regarding the fetishization of the murderess. In her 1958 novel The Sundial, she deviates slightly from the gruesome and snobbish joy of the Halloran’s in the midst of an apocalypse to discuss Harriet Smith, a previous member of the village which happens to be Fall River, Massachusetts. Harriet is also rumored to have murdered her family, and she has also been acquitted of the crime. Yet her presence and her house’s presence still draws in the same terror/fascination that fuels the media and keeps small towns afloat with tourism:

During Harriet’s arrest and trial, the villagers had met more strangers than had ever come their way before, and after Harriet’s acquittal it was customary for almost daily groups to get off the bus … and wander, guided by a villager, up the half mile to the Stuart house, where they were occasionally rewarded by a fleeting glimpse of Harriet’s housekeeper … who must sometimes have wondered if Harriet’s hammer days were over…

The home of Lizzie Borden did not officially open to the public as a museum/bed & breakfast until Martha McGinn inherited the property in 1996. While it is certain that tourists made their way to 92 2nd St. well before then, it did not become the bucket list item of horror fans everywhere until the ghost tours and well-stocked axe-shaped keychains. Yet Jackson predicts the thrill of peering into the Borden (Smith) windows with uncanny prescience. As onlookers peer over fences to see Harriet Smith in her garden, they don’t see a woman, but instead something supernatural or cryptozoological. Often, when consumers read headlines involving women and crime, they don’t read journalism; they read folklore.

How many can even name the victims in what journalism has referred to as the Amanda Knox or Casey Anthony murders?

In 2017, the names Shirley Jackson and Lizzie Borden remain intertwined through their paralleled sensationalism. Jackson’s works have been rapidly adapted into Netflix originals such as last year’s I Am the Pretty Thing that Lives in the House (which included a striking image of a young girl wielding an axe) and the mini-series based on her most famous ghost story of the same name, The Haunting of Hill House, starring Carla Gugino. Likewise, Lizzie Borden will soon be on the silver screen in Lizzie starring Kristen Stewart.

Odd girls everywhere surely rejoice in such adaptations that speak to them on an intimate level, because we, too, feel the weight of the spectacle and, perhaps, we, too, engage in its exploitation. It’s a paradox of perpetuation, and I have taken heed of Jackson’s wise warnings against it. Now, perhaps more than ever, we as a society must be careful that our gift shop keychains don’t become the very torches of media that continually burn women at the stake.