Both/And

As a Black Trans Man, I Refuse to Be Pathologized

Forced disclosure in medical settings makes trans people vulnerable to inadequate medical care

My intersectionality is a bullseye in the culture war spotlight. My wife and I conceal our growing worry within the safety of our floor-to-ceiling black-out shades in our bedroom. The surge of state bills targeting access to gender-affirming care have been proposed and mis-sold under the veneer of saving minors from child abuse, experimentation, and genital mutilation. One of these bills would prohibit institutional recipients of public funds from offering trans care for both adults and minors. Trans families and physicians are under attack. Politically and physically. Another bill proposed would make it a felony for physicians providing gender-affirming hormones or surgery to anyone under twenty-six. In this fast-moving dystopian reality, I wonder where we’ll find safe harbor? Stealth isn’t the answer.

My neck, its circumference, was the last thing to out me.

“Your neck is on the small side,” Dr. C. said after he glanced down my throat. I was at my first appointment with a sleep medicine specialist who, serendipitously for me, was a pulmonologist. In response to the “any changes” question during my annual physical, I’d told my primary care nurse practitioner I was waking up at night gasping for breath. At the time I had no understanding of the correlation between the circumference of one’s neck and obstructive sleep apnea. The one thing I thought I knew about the disorder was that heavy snorers are often diagnosed with sleep apnea and treated with a dreaded continuous positive airway machine. When I told my cousin I might have sleep apnea, she asked if I wanted her unused CPAP. She went on to explain she was tested, retested, and ended up with a machine she didn’t need because of (expletive) false positive results. Dr. C.’s eyes lingered a bit, refocusing on my head and neck.

I’d told my primary care nurse practitioner I was waking up at night gasping for breath.

“What size shirt do you wear?”

I re-looped a KN95 around my ears, wiggled the black cone to adjust its nose piece underneath my glasses before I responded. According to a tailor’s tape, my neck is slightly below fifteen inches with space to sneak in two fingertips. One reason I round up whenever I purchase dress shirts (slim fit) is to make more room. Fudging my neck size allows more space to tuck tails down and around my hips. Slim fit eliminates any bagginess around my chest and lats. I wasn’t sure Dr. C. cared about my arm length.

“Fifteen and a half,” I answered.

Apparently, a thick neck—considered 17 inches or more for a man and 16 inches for a woman—may indicate a narrow respiratory airway making it more difficult for air to flow to your lungs. Excess fat around your neck can also narrow your airway when you lie down. According to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s explanation of obstructive sleep apnea, if air needs to squeeze down your throat to your lungs you can end up snoring or wheezing, and if your airways become fully blocked you might stop breathing all together. The truth is at my age, I have the beginnings of a slender turkey neck. My body is aging like a luscious leather couch planted in a bay window alcove — cracks are starting to show. I’ll yield to the possibility my brain container appears small(ish) for the sixty-three-year old transman that I am today.

Dr. C. looked at his computer. I could tell he doubted the veracity of my stated shirt size.

“Did someone take your weight?”

“No.”

“That’s alright. How much do you weigh? I can type it in.”

“Back down to 165,” I said. I was proud and feeling good again after four months of a low-carb slog, ditching my pandemic backslide of double IPAs and sourdough pretzels, flourless chocolate cake and champagne.

“And your height?”

“Five eight. Well. More like five seven and three quarters since I’ve gotten older.”

“I’ll give it to you. But your BMI.”

My father was six four with what I imagine was an average body mass index most of my life. My brother is six two, played Pop Warner from Pee Wee through high school, was probably hitting two thirty the last time I’d seen him before our estrangement. Men on my mother’s side on average are shorter than me with a few exceptions. Black, Filipino and Austronesian lineage. My mother’s mother stood about four seven; at five six my mother towered over her sisters and some of her brothers. Maintaining her weight at or below a hundred and fifty pounds was an unfortunate obsession she ported over to me when I weighed in at one fifty around my 12th birthday. She drove me to her diet clinic that pumped me with HCG extracted from urine of pregnant women to make her feel better. The shots had the opposite impact of their intent: all I wanted to do was binge on ice cream and See’s Candies.

The shots had the opposite impact of their intent: all I wanted to do was binge on ice cream and See’s Candies.

BMI talk from a sleep doctor was borderline triggering. Without putting a finer point on his reference to my body mass index, Dr. C. said, “Your lung volumes are on the lower end.”

I thought about my lungs growing up in Los Angeles during the sixties and seventies when hazy smog concealed the magnificence of the San Gabriel Mountains. My father chain-smoked Winston cigarettes unfiltered before switching to Marlboros. I told Dr. C. I was exposed to my father’s second hand smoke.

Back then, I was enamored with my father’s smoking and wanted desperately to emulate it. Fake smoking with fingered air cigarettes was a regular part of playing alone in my room. I interpreted my father’s smoking as a feature of masculine strength, not a component of any toxic meditation practice. My mother’s mother smoked too. Granny struck her matches on the bottom of her pink slippers. One day my parents gave into my incessant requests to smoke. I was six or seven. I remember my mother led us into the bathroom upstairs and allowed my father to give me a puff of a cigarette he ceremoniously lit to prove their point. I gagged. They chuckled. I cried. “See!” my father said. “Told you so,” my mother said. I don’t remember which one of them threw my cigarette into the toilet bowl. It didn’t matter. Supervised smoking and quitting in the second grade happened quickly. Dr. C. didn’t seem interested let alone have the time to hear about my recollections of secondhand smoke or my parents’ experiment.

“What do you do for a living?”

“I’m retired.”

“And before you retired?”

“Corporate finance.”

“So, you understand ratios.”

I started to worry as Dr. C. launched into a cursory explanation that my lung volumes and other pulmonary function results were outside of the normal range compared to reference values. “Does it matter…,” I began. I heard the pitch of my voice change and cadence slow as I wondered if his medical opinion regarding normal was being filtered through the biological lens of male and female expectations. His expertise brought him to size — head, neck, lungs, one’s respiratory system, the interpretation of capacity curves informed by computed biological sex norms. “The way you’re describing this, does your birth sex matter? I’m transgender. I was born female.”

Based on years of experience I’ve learned to be rudimentarily clear with healthcare professionals regarding gender identity. For example, I imagine it was an assumption about my first name coupled with an attempt at culturally competent thoroughness that caused a nurse practitioner new to me to ask the date of my last prostate exam on a telemedicine videocall. When I chuckled that I didn’t need it, she countered in a tone of admonishment the importance of health screening, as if I were just another obstinate (i.e., Black) patient. As far as I was concerned, all I was doing was going through the motions to get a testosterone refill electronically transferred to CVS. Check the box, let’s move on. Mandatory biannual bloodwork, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, isn’t necessary anymore since I’ve been on T over twenty-five years. The substitute NP saw me, heard me, and yet assumed estrogen refill (which was ridiculous.) “This is a first,” I said to her with an edge of incredulity after I realized I had to articulate I wasn’t born with a prostate.

“Of course, it matters! Gender is not sex,” Dr. C. said in a slightly raised erudite tone.

Here we go, I thought to myself. I had gone from chatty and open about my symptoms to a vulnerable trans person in an unfamiliar healthcare setting — exposed. Decades earlier, an urgent care nurse at Alta Bates Hospital in Oakland practically cursed me out as she took it upon herself to shame me because I misrepresented my sex, despite the fact I was legally male by then with an amended California birth certificate to prove it. I remember her face turning sunburn-at-the-beach pink, her voice raised like Dr. C.’s as she walked out of the room.

I was in for a tetanus shot. To be fair, she was trying to make sense of a potential duplicate medical record. There was someone named Anastasia Cecilia Jackson, same date of birth and social security number in their system. Years later I was instructed to make a 45-minute drive to California Pacific Medical Center’s emergency room in San Francisco because of a two-day 104 fever after my phalloplasty procedure. The attending nurse insisted they perform a rapid HIV test after I “revealed” I had received bottom surgery weeks earlier in their gender clinic. She initially responded with a WTF stare, and began asking questions about my status, which after further probing I realized was shorthand for my history of sexual activity and IV drug use. Fever is a symptom, but I tried to explain that I doubted HIV was the culprit lighting my body up and rolling me into her emergency room. She pushed back and said we needed to rule out HIV. Hours later I was admitted into the hospital to combat a UTI.

Dr. C. scrambled up and out of his chair. “I’ll be back. I’m going to rerun the test to see where you fall within the other ranges. I’ll do it myself,” he said this time in a hushed tone, as if he were a priest in a confession box administering five Hail Marys and two Our Fathers, sworn by an oath to keep my sin of gender omission between the two of us. The way I saw things, a one-sided discussion about assigned sex with Dr. C. was due to an outdated binary intake system. My new dermatologist’s webform asks for birth sex, gender identity, and pronoun preferences. But she is a Black physician and dermatological surgeon running an award-winning medical and aesthetic practice. Based on Dr. C.’s quip about gender versus sex, it could have gone either way in that moment — he could (re)make some attempt at cultural competence or be the bearer of righteous indignation under the guise of the Hippocratic oath in reverse, as if I had broken a covenant of my divine duty to disclose in a medical setting that I was born with XX not XY chromosomes.

My fear and simmering rage aside, in 2002, Bellemare, Jeanneret, and Couture published results from their study Sex Differences in Thoracic Dimensions and Configuration. They concluded the volume of adult female lungs is 10 to 12% smaller than males of the same height and age. Unaware of this data at the time, I waited for Dr. C.’s clandestine analysis using an updated set of female reference values, back to so-called normal.

The way I saw things, a one-sided discussion about assigned sex with Dr. C. was due to an outdated binary intake system.

Intellectually I understand disclosure. How else will providers know the appropriate care to administer if you can’t speak for yourself? Despite the misdiagnosis risks, I’ve treated my birth sex as HIPPA PHI on a need-to-know basis. The one exception to my current rule is primary care. Even then, I tend to omit surgical plus minus additions and subtractions, revisions, ‘ectomies and ‘plasties on generic intake questionnaires. I choose to forego the zoo animal observation in the name of scientific curiosity (i.e., medical education) until I can build a mutual relationship of trust. I once had a urologist at a teaching hospital ask if his students could look at my ding-a-ling. Never again. I will not be pathologized. Disclosure needs to have a pertinent purpose. So no, my dental hygienist does not need to know my testicular implants were taken out because the silicone alternative was too hard and interfered with my road bike performance. Chafing is bad enough on long rides for anybody, even with high quality butt butter!

Dr. C. was taking a long time. Five minutes by myself was nerve wracking. I was in a sparse unfamiliar room within a department treating patients with asthma, COPD, cystic fibrosis, and lung cancer among other respiratory system issues. The breathing test administered right before felt like my nose had been clamped shut with a binder clip. I was instructed to wrap my lips around a tube with a mouthpiece that looked and felt like a snorkel. I hadn’t expected tubes and wiring for a sleep study referral. Before the diagnostic probing, I knew my lungs had scar tissue based on an X-Ray performed for an unrelated medical procedure in college. “Let me try it again. I can do better,” I cajoled the respiratory technician with a resonant tone I hoped she understood (sis, gimme another chance.) “Mm-hmm. I don’t want to use this because I need three good measurements. I can throw one of them one out.” I had no idea how to interpret the graphical lines being mapped real time when I turned my arthritic neck to the right. I felt discouraged I couldn’t blow with the force she encouraged, “keep going, going, exhale; take a deep breath; is your tongue in the way? There needs to be a good seal.” “Yep,” I grunted which sounded like a weak muffle down the end of a blocked megaphone.

We kept at it. In the moment, attempts to achieve the best results seemed more about her skill as a respiratory technician than my limitations. She was distracted throughout the test. I overheard her on her mobile with a care giver of a relative, excusing herself multiple times between measurements, in and out of the spirometry equipment room. Perhaps that explained why there was no height or weight for Dr. C. But my struggles inhaling and exhaling? There is no other way to put it. My lungs suck! This is a feature of my lived experience that didn’t need spirometry validation.

I had pneumonia twice before the eighth grade, with multiple bouts of bronchitis during flu and allergy seasons my entire life. Because of bronchitis, I missed a Girl Scout camping trip and was kicked off my high school swim team after three practices. Both absences broke my heart. More recently I got wet playing golf in coastal North Carolina during the summer of 2021. My brother-in-law and I cut the back nine short after funnels of charcoal clouds and thunder warned of fury rolling our way. The water was warm, my head and chest lightly pelted for five minutes before we drove the cart to the parking lot. It didn’t take much. Being outside in southern rain morphed into a month-long bout of spitting up thick yellow and occasionally brown mucous. A PCR test ruled out COVID-19 which I feared could blow up my fall writing residency. Bronchitis — my nemesis loving on me again. A course of antibiotics was required to fend off pneumonia. Trying to sleep with a rattling painful wheeze and a spit-bag reminded me of my childhood. Clueless and precocious, I used to fake-take tetracycline which I hated swallowing. I’d take the pellet in my hand, squeeze it between my left thumb and index finger, gulp my orange juice, and make a face with accompanying sound effects. Fake-take. When my mother left my room, I would drop the drug down the gap of my headboard. I was sick of taking pills.

I had pneumonia twice before the eighth grade, with multiple bouts of bronchitis during flu and allergy seasons my entire life.

During my gasping episodes my breathing is labored, like the time a kid who lived across the street beat the crap out of me. He called me bitch nigger after I threw a rock into his boy pack in the suburbs of LA County where name-calling happened on the regular. I picked up a blue grey Mexican pebble from my mother’s bonsai garden and connected with his forehead. He responded landing upper cuts on my solar plexus and floating ribs — my back pinned against siding near our front door which served as punching leverage. I remember my mother took me to the pediatrician in addition to calling the cops to submit a police report. “Did he call you names?” Bruised, too embarrassed to repeat the words to the officer sitting with me and my mother on our living room couch, I lied for my attacker, I lied to end the interrogation. I have no idea then or now what type of lasting damage the lung contusion from the old beat-down caused.

Dr. C. was finally back with a printout full of numbers. My rerun: female from male. His reinterpretation: “You’re still on the lower end. I’m going to order a sleep study and a CT scan to rule out bronchiectasis.” After a brief discussion on the benefits of a sleep study at home versus the occasional false negative results, we agreed to start in the comfort of my own bed versus an overnight stay in the hospital sleep lab. I wasn’t referred to Dr. C. for an assessment of my scarred lungs, however if there was something to know I was open to knowing it. I kept the newly prescribed exploratory tests on the down low. I wondered aloud to my therapist what was beneath the surface of my trepidations of sharing my latest referral with my wife. It wasn’t the first time I omitted certain details regarding tests or treatment.

I lied for my attacker, I lied to end the interrogation.

Distrust of doctors and nonprimary care providers by Black people has been well documented and researched given racial disparities in health and the traditional healthcare system. The NIH’s National Library of Medicine’s website is populated with abstracts such as:

- African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: healthcare for diverse populations

- Disparities and distrust: the implications of psychological processes for understanding racial disparities in health and health care

- Knowledge of the Tuskegee study and its impact on the willingness to participate in medical research studies

Neither my mother nor my father as senior citizens in their seventies appeared to trust doctors, resisting recommendations to take medications or perceived invasive interventions. My mother railed against treatment for my father to me, proclaiming dialysis would kill him because she knew he would keep drinking vodka and OJ. On the other hand, my father appeared unwilling to exercise his agency over his own healthcare. Apathy is a form of foul play. Years after my mother died, my siblings found partially taken prescriptions in her bathroom during their preparations to sell our family home. Previously my mother confided she had blood in her stool, however my sister-in-law supported my mother’s subsequent proclamation that all she really needed was a good night’s sleep. My mother’s vital signs were literally fine on her death bed. Who knew vitals don’t reveal the complete picture of a body’s deterioration?

Repeat: You are not your mother. You are not your father.

The first time Dr. C. and I had exposed our unmasked faces to each other was on a telemedicine video call to explain the results of my CT scan. We exchanged pleasantries as if we had never met. The virtual face-to-face felt more intimate than meeting in person masked up the prior month. Moving on to the point of the chat after smiles of acknowledgement, Dr. C. said despite the cyst and nodules, he wasn’t too worried about my lungs if I scheduled annual CT scans from now on. “Now we have a baseline,” he said.

The fact that I don’t have significant obstructive sleep apnea requiring an intervention is a partial victory for me, my gasping awake while asleep still unexplained. The cardiologist I chose to see practically escorted me out of his office with a COVID arm bump and a smile. There was no reason he needed to see me again; he confirmed my heart is healthy. Left to my tendency for hypochondria-fueled research on the Internet (yeah, sure; I admit it), I have concluded the source of my gasps is likely nocturnal panic attacks. The symptoms of a nocturnal panic attack according to the Cleveland Clinic are chest pains, chills, intense feelings of terror, nausea, profuse sweating, a racing heart, numb fingers, toes, trembling or shaking. The research shows nighttime panic attacks present more severe breathing symptoms like gasping for air versus an attack during the day.

I have concluded the source of my gasps is likely nocturnal panic attacks.

As a trans family specifically, my wife and I have both been sleeping on the edge of gasp. Mortal stress has been lurking. Swallowed. Pushed down. I know there is a collective fog of panic in the circles I belong. Culture has been weaponized; red and blue and purple states marked. Book banning. Trans kids, trans athletes targeted. Marriage equality shielded at the federal level. Some claim COVID is a sham. They say critical race theory is to blame. Blue lives matter. More guns — concealed weapons even better. States’ rights to elevate sperm and criminalize choice is terrifying. What’s next? Will the Thomas un-Supreme Court hint at its desire to accept private insurance cases addressing the legality of denying trans health, including puberty blockers, gender affirming mental health, as well as hormones and surgery? Will my F to M gender reassignment be criminalized, monitored by gender vigilantes if states legislate their “right” to protect gender-conforming citizens from moral corruption that could spread to their families?

While sleeping I gasp myself awake sometimes, and occasionally shriek, settled by the soothing sounds of my beloved telling me it’s (just) a dream. Perhaps a consistent deep breathing practice without another medical referral is all I need. We shall see.

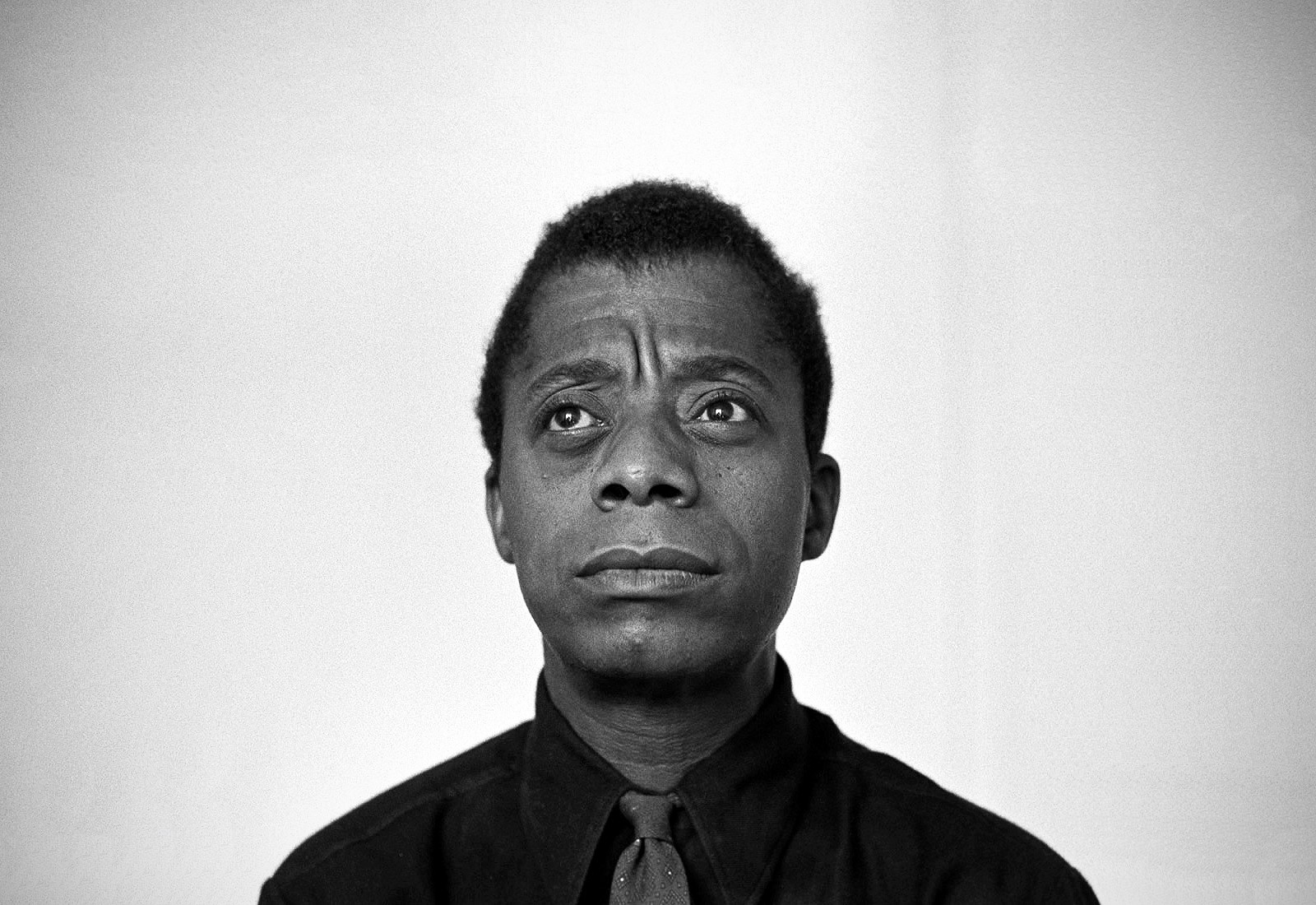

This essay, by Stacy Nathaniel Jackson, is the seventh in Electric Literature's new series, Both/And, centering the voices of transgender and gender nonconforming writers of color. These essays publish every Thursday all the way through June for Pride Month. To learn more about the series and to read previous installments, click here.

—Denne Michele Norris