Craft

Warning: Family History May Cause Writer’s Block

How to risk failure and do ambitious shit when your ancestors are watching

At 5:15 in the morning, I tiptoe across my kitchen floor and pray it doesn’t squeak in that one spot where it always squeaks. I don’t pray often, but these are desperate times: I have a small child and forty-five minutes to write in solitary silence. With a baby monitor and a cup of coffee in front of me, I open my laptop. The cursor blinks as if to say, “Now what?”

I’m working on an essay about re-learning Cantonese, the language I grew up speaking. Of course, it’s about more than that. It’s also about the pain of losing your cultural identity. It’s about what’s lost from one generation to the next. At least, that’s what the essay would be about if I could write anything at all. When does writer’s block become an actual medical condition? Should I call my doctor if symptoms persist for more than six weeks? Stephen King says the best way to beat writer’s block is to write with the door closed—my door is wide open, and my audience, if you can call them that, doesn’t even bother to knock. I stare at the blank screen and realize I’m holding my breath and grinding my teeth as they stand in the doorway wondering what the hell I’m doing. They, my ancestors.

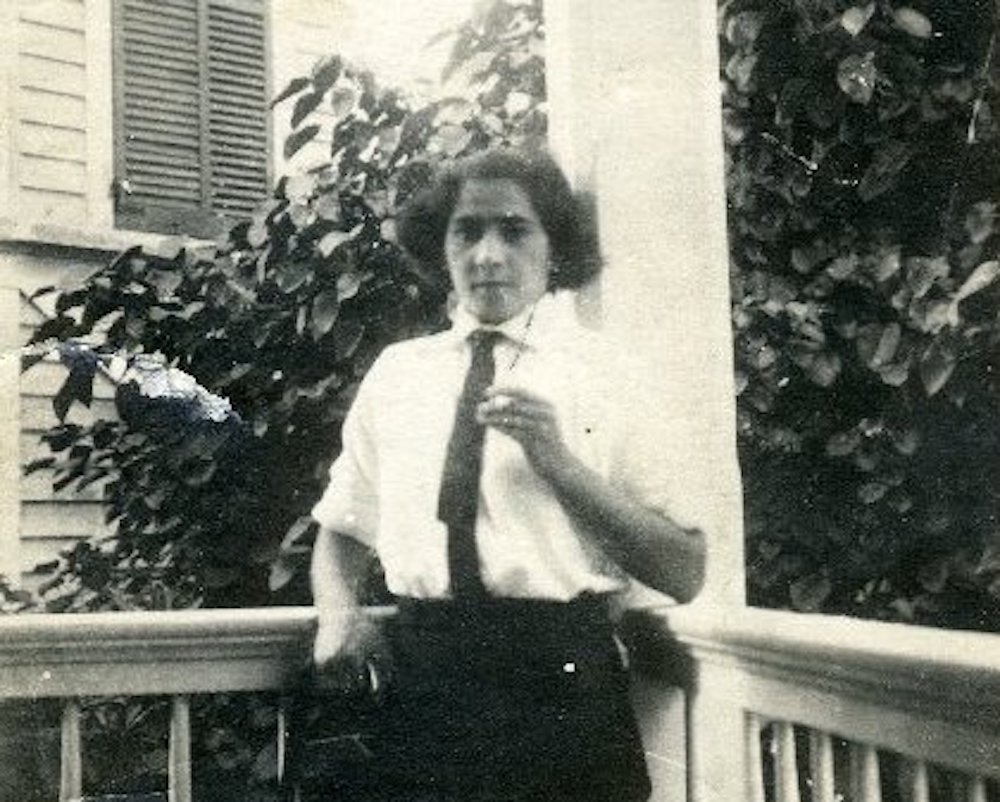

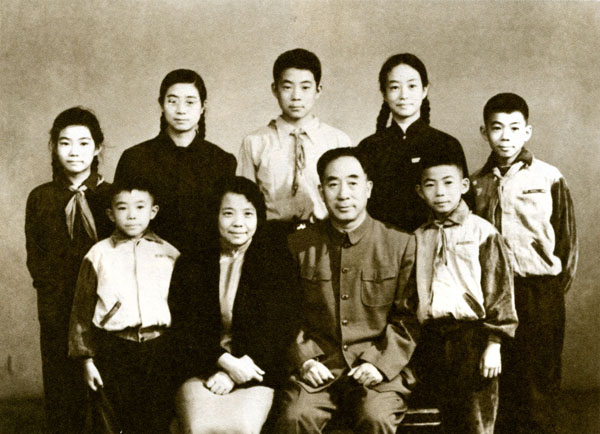

My mother immigrated to the United States from Hong Kong in the 1970s. If you ask her what she found most surprising when she got here, she’ll tell you it was the grocery stores. Aisles and aisles of mass-produced meat, snacks, and desserts, loaded up in buildings the size of airport terminals. It was so different from the open markets she grew up with in Hong Kong, where vegetables were laid out on rugs and ice cream was sold by the slice. Here, in the United States, she could buy a whole gallon of ice cream—enough to get a tummy ache. She’d throw the rest down the garbage disposal, another novelty my mother couldn’t believe. She has always loved to tell me things like this. Stories of life back in Hong Kong. How she and her siblings shared a tiny bedroom with another family because they had nowhere else to stay. How my great-grandmother’s home was ambushed during the Chinese Civil War. How my great-great uncle came here to build the railroads and was treated so poorly that he returned home to report, “Even if all you have is a sidewalk to sleep on in China, never go to the United States.”

. . . Do you see what I mean? It’s hard to not grind your teeth when it’s your job to tell a story, and these are the stories that came before you.

My family loved to neutralize my complaints with their own, which, of course, were always so much worse.

When I was a kid, I would pretend not to care about my mother’s stories. “You think I had it bad?” she’d say, “You should talk to grandma—now she had a tough life.” I knew I should pay attention, but when she talked, I would dig my nose deeper into whatever Baby-Sitters Club novel I was reading. I don’t know why I did that. Maybe I wanted to prove that I wasn’t impressed by her struggles because I needed mine to feel important. Who could blame me? My family loved to neutralize my complaints with their own, which, of course, were always so much worse. I’d complain about mowing the grass in the Texas heat, and my mom would say, “I used to cut grass with scissors.” I’d complain about not being allowed to shave, and she’d say, “Be grateful for your hairy legs—better than going to bed cold.” I once made the mistake of complaining to my aunt that I had to run four miles every day at soccer practice. “Kristin, just be happy you’re alive,” she said, as if death were the only alternative to junior varsity soccer.

Or maybe I didn’t listen because I was scared. The life my mother talked about in Hong Kong looked so different from the one I was planning for myself. She grew up hungry and poor; I watched Saved by the Bell and took gymnastics lessons. She worked minimum-wage jobs to put herself through night school; I was going to college someday. Her goal was to survive; mine was to find a career I loved. Even as a kid, I sensed the tension between preserving my family’s past and planning for my own future. It felt like a betrayal, and I wasn’t ready for those feelings back then. So, I pretended not to listen. My fingers hover over my laptop keys and I look up. My ancestors are still there, nodding as if they knew all of this all along.

“Ah, a writer. So you don’t like making money?” my uncle asked when I revealed my aspirations to him. We were at dim sum, and it was a family reunion of sorts. I hadn’t seen him since I was maybe . . . ten? Now, I was a teenager writing for my high school newspaper. He asked what I wanted to do with my life, so I told him. I was prepared for his response and knew not to take it personally—our family was very practical about these matters. Still, I protested. “Didn’t our family come to the United States for a reason?” I argued. “So we could have a better life? Don’t you want your kids to have the chance to choose what they want to be?” My uncle finished a mouthful of har gow and smiled. “Not really,” he said.

It’s hard for second-generation kids to tell their immigrant parents they want to be writers, actors, or illustrators. Or anything creative, really. By and large, our parents want us to become doctors and lawyers because that’s the most likely path to financial success. And you can’t really blame them. Our country treats immigrants like commodities. Even the most well-meaning policymakers argue that immigrants deserve to be here, not because they deserve a shot at survival, but because they’re good for the economy. So if your family immigrated here and you don’t earn six figures, you sort of feel like a guest who showed up to a party without bringing a bottle of wine.

It’s hard for second-generation kids to tell their immigrant parents they want to be writers, actors, or illustrators.

In a culture where people are only as valuable as their output, earning a ton of money can seem like the best way to gain respect. It’s why so many people believe that you can fight discrimination by getting rich. It’s also why children of immigrants feel isolated from their ethnic communities when they choose creative careers. If we’re not earning a ton of money, we feel like we’re letting down our ancestors. As one Big Law attorney put it in a viral TikTok video, “Yes, it’s fuck capitalism. But my family didn’t fly halfway around the world for me to be a broke bitch.”

I didn’t commit to being a broke bitch right away. After college, I took on a technical writing job at a Big Evil Corporation where I wore slacks and made lots of money. I had extravagant perks, like, you know, health insurance. But I couldn’t shake my desire to write for a living. So after a few years of living in luxury—treating my friends to dinner, going to the doctor when I felt sick—I decided to take the leap. I wanted to save up some money, quit my job, and move to California to be a freelance writer, maybe even write for television. It was a risk, but I saw myself as a “calculated risk-taker.” I told my therapist about my game plan; I created a whole spreadsheet with strict deadlines for every milestone I planned to hit. By the end of the year, I would save six months’ worth of living expenses. By the time I moved, I would have two freelance gigs secured. My therapist smiled at me the way you might smile at a puppy for stepping in its own shit. “Well, don’t forget to have fun,” she said. “Isn’t that the whole point?”

I can see my grandmother laughing in the doorway as I type this. “Who has time for fun?” she says in Cantonese. Another voice, I can’t quite see who it is, chimes in, “Somebody has to pay the bills.” An aunt, maybe. Or my mother. Maybe it’s me.

All of this might sound contradictory. If I’m such a stickler for playing it safe, why would I choose a creative career to begin with? That’s the thing about coming from an immigrant family, though. You are fearless and terrified at the same time. You feel scrappy enough to do ambitious shit, but you’re also terrified of failure. Most people are afraid of failure, but this kind of failure is different. As the child of an immigrant, you need to earn your place here, so if you’re bold enough to go down an unpredictable or unconventional career path, you sure as hell better get rich doing it.

Of course, there’s also the guilt that comes with being the offspring of survivors. “Survival” is one of those words that has evolved to mean just about anything. When my mother talks about survival, she means having enough food, having shelter—you know, not dying. For me, survival is getting through a particularly stressful day of click-clacking on my computer while I decide if I have the energy to go grocery shopping because we’re out of La Croix. “How was your day?” my husband asks. “Fine,” I tell him. “I survived.” Sure, my ancestors wanted a better life for their descendants, but is this what they had in mind? Honestly, I’m not even sure my ancestors would like me. I’ve been writing this whole time, and they’ve been sitting there with their arms crossed, shaking their heads.

As a kid, I had grand ideas about what a writer’s life looked like. It was plugging away on a typewriter in a remote cabin in the woods. Or scribbling down brilliant ideas at a retreat in southern France. As an adult, I know these are myths about writing that most of us don’t get to experience—but they’re alluring, aren’t they? For most of us, writing is jotting down notes in your car when you get a break at your day job. Or squeezing in time to write when your kid goes down for a nap. Sure, there are also those moments you wake up with a warm cup of coffee and a silent house and get to feel like Ernest Hemingway for thirty minutes before your kid starts crying or your husband wakes up and tells you how poorly he slept. Those moments are rare treats. By and large, though, the creative process is a struggle.

Maybe the more important question is: why write in the first place? I recently read that writing is a way to live forever—“little bids for immortality,” as the writer Elisa Gabbert put it. If we can find the right words to describe our thoughts, feelings, experiences, and histories, then it’s sort of like our consciousness will live on without us. The alternative, if we don’t manage to tell the stories we want to tell, is that our stories will disappear when we do. Our ancestors will die along with them. My son will look out of the car window on a road trip to Sacramento, see a train passing by, and not even know that his ancestors built those tracks. He’ll never know his grandmother shared slices of ice cream with seven other siblings. Or that his great-great-grandmother used to pluck grub worms out of her rice buckets and say, “Look at this fat bug, trying to eat all of our food.” It’s my job to tell these stories, even if he pretends not to listen.

My ancestors are harsh editors. They hover in the corner every time I sit down to write these stories. But like all good editors, maybe they just want to do the story justice, not only for the people who came before me but for the people who will come after. We are, in some ways, collaborators.

In two hundred years—maybe even fifty, maybe even now—no one will care about my little Cantonese essay. It will disappear into the infinite timeline of existence (or the internet). So why do I keep writing? Why do I sit here with the door wide open, desperately trying to tap into my creativity? I guess because, like my ancestors, I am trying to survive. And writing is the best chance I’ve got.