Lit Mags

Win a Round Trip to Complete Oblivion

"That Old Seaside Club" by Izumi Suzuki, recommended by Makenna Goodman

Introduction by Makenna Goodman

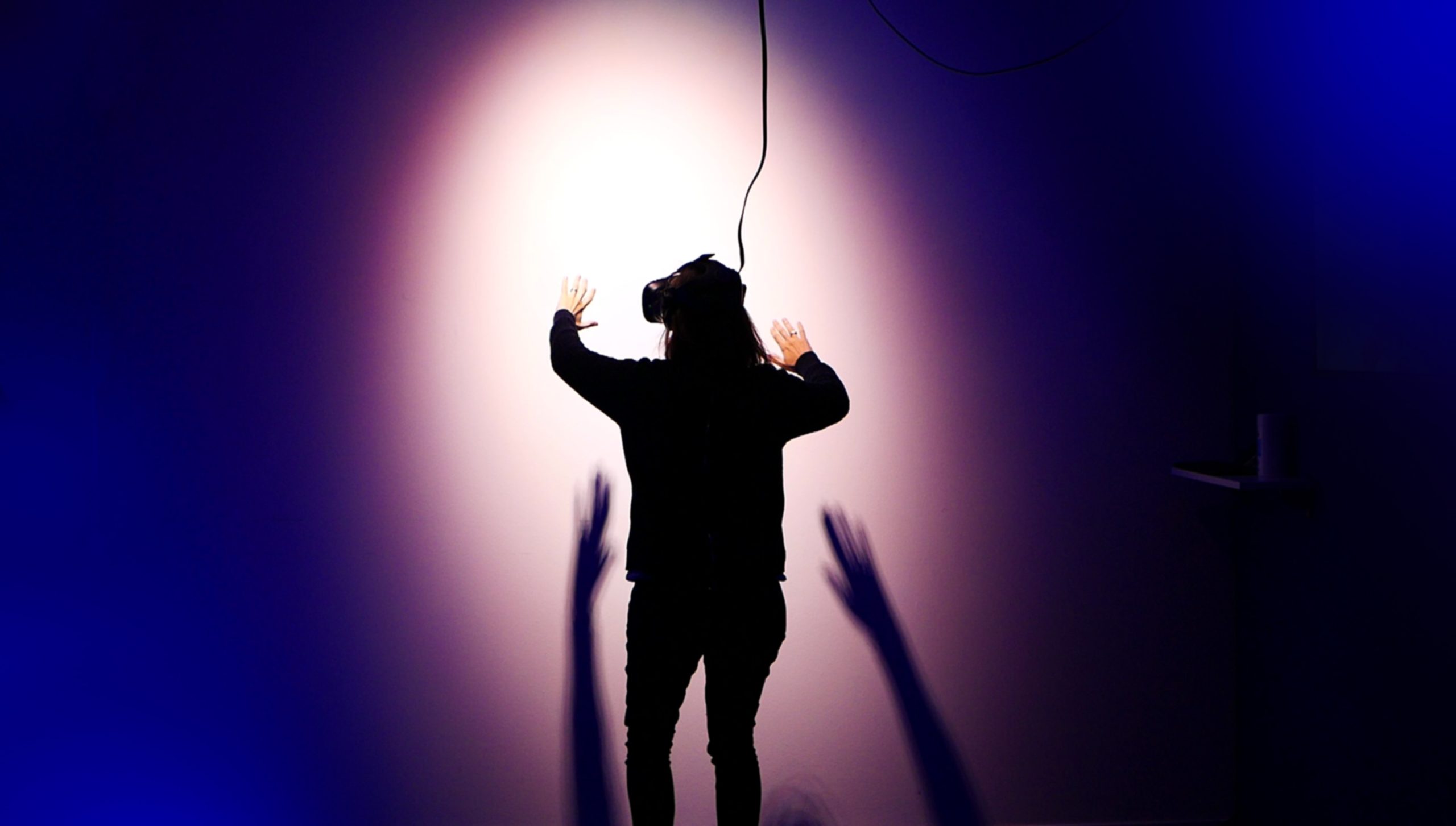

I love reading books where reality is warped into something dreamlike. Writers who do this well offer us a chance to exist as if alone in a room surrounded by mysterious darkness, while at the far edge of the room is a hole glowing with golden light. Peering through it, a brightly lit room becomes visible, a staged tableau of humanity. While we know it isn’t real, it suggests the larger idea of “truth,” allowing us to suspend ourselves in meaning as if in a tank of salt water. We don’t need to see all possibilities to know they exist, just as we can imagine a vast ocean by holding a simple shell. Art allows for this distance, in an effort to get closer.

I love reading books where reality is warped into something dreamlike. Writers who do this well offer us a chance to exist as if alone in a room surrounded by mysterious darkness, while at the far edge of the room is a hole glowing with golden light. Peering through it, a brightly lit room becomes visible, a staged tableau of humanity. While we know it isn’t real, it suggests the larger idea of “truth,” allowing us to suspend ourselves in meaning as if in a tank of salt water. We don’t need to see all possibilities to know they exist, just as we can imagine a vast ocean by holding a simple shell. Art allows for this distance, in an effort to get closer.

The writer Izumi Suzuki, an icon and pioneer of Japanese science fiction, came of age in the 1960s and was part of Japan’s artistic avant garde; she worked with the photographer Nobuyoshi Araki as well experimental film directors Shūji Terayama and Kōji Wakamatsu, and was married to the free jazz saxophonist Kaoru Abe. Suzuki died at 37, in the middle of the 1980s, completing her best work in the last ten years of her life. Despite being an outsider in the science fiction world during much of her career, she is compared to Philip K. Dick, Ursula Le Guin, Anna Kavan, and others, having paved the way for many contemporary Japanese authors including the brilliant Yōko Tawada and Haruki Murakami. Suzuki’s work, now released in English for the first time, marks an exciting moment. Its themes feel of-the-moment despite being written over thirty years ago, and yet they are also surreal—the imagined artificialities of the 1980s written as futuristic now mirror our mundane, modern technology.

In “That Old Seaside Club,” a story from Suzuki’s newly released collection Terminal Boredom (Verso), a woman plays out her fantasies of who she might be if she had learned how to be happy. A barman serves her and her friend drinks at the Seaside Club, a bar in a world where money doesn’t matter and people are free to live the life of leisure their normal lives could never provide. The narrator flirts with a strange man who strikes her as oddly familiar…and he is…but she can’t place him. The mind plays tricks; perhaps we’d be happier if we let it have complete control. The story seems to ask: if we allowed ourselves to relive our memories again and again, could we edit our fate?

At one point in the story, the narrator talks to Chair, a chair who reminds her of her mother, and speaks just as harshly. Has she gone mad, the narrator wonders? Chair replies: “You get doors and microwaves that talk, don’t you?” The narrator retorts: “That’s because someone’s made them that way!” Suzuki asks us to entertain the possibility that reality itself may be more surreal than fabrication—or just as artificial.

– Makenna Goodman

Author of The Shame

Win a Round Trip to Complete Oblivion

Izumi Suzuki

Share article

“That Old Seaside Club” by Izumi Suzuki

Sunlight floods the bay.

Boys and girls sit on benches beneath the canopy of trees lining the walkway, lapping at ice-cream cones. Others cut zigzagging paths down the walkway on their roller skates. Red and white parasols shelter hot dog stands.

I begin whistling, both hands shoved into the pockets of my denim skirt. The low notes blend together. If I try to whistle too hard, I veer off-key. I can’t properly separate the notes of fast songs like this, so they end up merging into each other.

Doesn’t match my mood, but I change to the blues. This way, you see, it doesn’t matter if the tune wobbles a bit—you can still make it to the end.

Oh, each day is such a gift.

I’m having so much fun that I can’t hold back my smile.

But what manner of idiot just stands there grinning all the time? So, I sing these songs all day. I’ve been like this ever since coming here.

A bus pulls up from behind, letting off Emi. She gives a big wave and runs up to me. “Where you off to?” She smiles, and a warm breeze teases her curly hair. Then, the scent of the sea.

“The Seaside Club.”

“Oh, same here!”

The sign outside of this bar on the outskirts of Yokohama actually reads “Serenity.” Kind of sounds like somewhere you’d go to “die with dignity,” to be honest, so we’ve chosen our own name for it. And everyone here just calls this area “the seafront.” Some folk go for “coastal promenade,” but who knows what they’re on about. Emi and I walk along by the pier, looking at the Hotel New Grand off to the side.

The melody in my head goes on, coming out as a hum now, not a whistle.

“What’s that one called?” Emi looks at me.

“Can’t say. I’d have to get back around to the hook first.” I’d stopped following the lead guitar to answer her, but I pick it up again straight away. Emi joins in with an organ-like tone. Our jam continues, on and on.

And there’s no stopping us, not even now we’ve reached the Seaside Club. The mood of the piece has become quite melancholy, or serious, but it’d be no fun to cut it off, so we stand there, carrying on. Finally, we find a chance to get back to the hook. She seems to know the song too, and we really get into it. And, like an avalanche (or so we think), we slide into the ending. The End. Or not—I decide it was a pause, and then add one last phrase. If I had a guitar, I’d be playing a trailing solo that lingers through a slow fade before disappearing, like a whistle in the darkness.

“What was it, again?” I ask, pushing open the glass door of the bar.

“‘I Can’t Keep from Cryin’ Sometimes,’” Emi answers quietly.

Can’t help but cry. True that. But I wonder why a song with a title like that came to mind.

Anyway, we make for the bar stools as usual, without giving the song any further thought.

“It’s just beautiful outside,” I say to the bartender.

“It’s always like that here. Everyone’s so content at first,” he replies, coolly.

“What’s that supposed to mean? You can live a life of absolute leisure here.”

I’d won my place in a lottery. The ticket came with some tissue paper I’d idly bought . . . I think. (My days here are like tissue paper too, I suppose—I float around, dazed, and any memories of the past are blurred and hard to pin down.)

“Oh, but you’ll tire of that. If you’re a committed sort.” This barman likes to get up on his high horse.

“We can stay here as long as we like, can’t we? And we’re free to go back to Earth any time,” Emi says, fiddling with her paper napkin.

“Technically, I suppose. Do you want to go back?”

“No, no,” she shakes her head, “I’ve only been here half a month.”

“Wait!” I turn to her. “Didn’t you say it was half a year, before?”

“I never said that.” She pauses a moment and adds, more sweetly, “You must’ve just misheard.”

One wonders. I mean, I’ve been here around a fortnight, and seeing as she was here before me . . .

“A beer, perhaps?”

“Oh, forgot to order. Yes,” I reply to the barman, “in a small glass, please.”

He places a delicate fluted glass on the counter, and then a freshly opened bottle. Emi glares as he performs this routine. She’s always like this when I drink.

“It’s the middle of the day, so . . . I’ll have something soft,” she says, slowly.

Emi didn’t win any lottery—she’s here for therapeutic reasons, a change of scenery. Apparently the air on this planet does you good. She says she’s twenty-five years old. I’m not sure what she was doing before coming here.

“Go pick some music,” she says quietly, her mind elsewhere. Stood beside the jukebox, I touch the screen and begin scrolling down through an endless stream of song names and numbers. There are enough records in this thing to fill an entire radio station’s back catalogue. I get sick of sifting through them all, so I just choose three tracks without much thought, and head back to the bar.

“What did you go for?” Emi props her elbows on the bar.

“Some rhythm and blues.”

“Nice.”

A shrill, tinny voice sings “Lucille”—could be a woman or a young boy. I spend a moment captivated by their strange enunciation, which wraps around the lyrics as if the words were the singer’s own. I take a sip of beer and put my glass down again. Emi glares fiercely at my hands.

“My mum, she . . .” After a pause, she breaks the silence. “She’s an alcoholic. Drinks from the morning and right on through. She doesn’t care, as long as she has her sauce. And it’s not about the taste—she says she never even liked it. But being a little tipsy helps take the edge off her pain, she says.”

The barman listens to her words attentively. Well, I suppose he always takes his job seriously. But once Emi started talking, a slight tension seemed to draw across his face.

“She’s always trying to quit, but she winds up reaching for the bottle again. One time, she went to throw away all the booze she’d stored up. Took me with her, too, all ceremonial. And when we got home, she was so happy—“Now I’ll never drink again!”—all of that. But just two hours later, she was getting restless. ‘I should’ve kept a little drop,’ she’d say. ‘Just enough for a little nightcap before bed.’ And before long she was out buying her bottles again.” She lets out a long sigh, her brows furrowed, and wipes her palms with a tissue pulled from her sleeve.

“And?” I ask, trying to sound as casual as possible. “Did she ever do anything to you?”

The color drains from her face. That seems to have unsettled her.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean . . .” Didn’t I? Well, then, what did I mean?

“It’s fine, I don’t care. You mean, did she hit me, right? Like some drunken guy on a rampage? No, nothing like that. But when my dad left for work, she’d grab a bottle and a glass and head right back to bed. When she was in a bad mood, she’d be like that all day long. Towards the evening, she’d start thinking about preparing dinner—but it’s dangerous, isn’t it? Cooking when your head’s all over the place—spilling, scalding, dropping knives everywhere. So she’d make something up about feeling unwell and go back to bed again.”

Emi wipes her forehead with the tissue.

“Shotgun” plays through the speakers, breaking the silence between the three of us.

“I wonder why I blurted all that out,” she whispers between the phrases in the music.

“Because of this.” I gesture to the beer before me.

“Yeah, that’d be it.”

“I’ll never drink in front of you again.”

“Oh no, that’s going too far.”

“But it reminds you of your mother, doesn’t it?”

“Yeah. It’s weird. A little while after I’d arrived here, she started really playing on my mind.”

A door opens and a young barmaid enters the room. The older barman takes off his apron. He only ever works extremely short shifts. I guess it’s enough to keep the place ticking over.

“What are you up to tonight?” I change the subject.

The barman begins clearing his things up.

“I’m going to Friday’s Angels,” Emi replies, mentioning the name of a kooky nightclub.

“Oh, great idea! Maybe I’ll come along.”

It’s my kind of place, old-fashioned interior. There’s a thickly carpeted floor, raised in bumps here and there for people to sit. And they don’t just play the charts—you hear some outrageous tunes in there. The other day they started playing some novelty song called “Don’t Feel like Doing Anything at All”, and I couldn’t get over it. And there are no kids on the scene.

“And hey, in that case,” Emi adds, “you might run into Naoshi. He’s always there.”

I feel myself blush. The sound of his name alone sets my heart racing.

“He’s cute, isn’t he?” She laughs. “Have you spoken to him, at least?”

“Not yet.” I shake my head, bashfully.

“Reckon it’ll take a while to get something going?”

The barman adjusts his scarf and leaves. I stare at my hands, gripping my beer glass.

“Well, who knows. Things can shift all of a sudden.”

I found him pretty much straight after I arrived on this planet. He’d come to the spaceport to meet some other girl, as it happened. And, oh, the wariness I felt then, and still now—and yes, that’s right. It was wariness, I’m certain. Not excitement.

I’d seen him before, somewhere. But how?

There’s no way I’d ever forget someone so beautiful. And, actually, rather than having seen him before, it’s like I’ve been involved with him.

“When I first laid eyes on him, I felt like he’d been someone close to me,” I say, absent-mindedly, “but I also felt this sense of coldness towards my own self; a distance from the version of ‘me’ that had been close to him. It’s a weird way of putting it, I know.”

“Hey, how old are you?” Emi sips her lemonade.

“Nineteen.”

“Right. So phrases like “I wanna live again” won’t have crossed your lips yet. She used to say that all the time at one point, my mum. ‘I wanna live again.’”

“That was a song, wasn’t it?”

“Oh, you can find a song for anything, you know. There’s even a song that goes, “This isn’t real love, it’s just a song”.”

Emi grows silent and starts picking at the peanuts set out by the barmaid.

“When did your mum say that?”

“When she was thirty-six. It was a dreadful age for her. All she wanted was to hit reset and start everything over again from twenty-five.”

“Twenty-five? Why so specific?”

“That’s how old she was when she got married.”

We fall silent again.

At some point the barman comes back. Music continues playing from the jukebox. Next up is “Love’s End Does You Bad.”

“I’m sorry. I’m all over the place at the moment,” Emi says, after a pause. “I keep remembering all these things from the past, without meaning to. And these memories—they’re so vivid. This stuff about my mum, I mean, it’s as though I went through her suffering myself.”

“It’s because you’ve got all this time on your hands.” I play with my silver bracelet. Emi’s wearing the same one—they have little discs on them that work as a sort of cash card. While we’re on this planet, nothing costs a penny. But neither the barman nor the barmaid wear one.

“You’re right. It’s so easy to end up imagining stuff when you’re idle.”

Seems like she’s got her mind on other things today.

A languid song, almost dripping with despair, comes on the jukebox. I check the screen—”I’ve Got a Mind to Give Up Living.” Paul Butterfield.

“Can I get you two anything else?” the barmaid asks.

We take the bus out of Yokohama as dusk nears. “What’s the next stop?”

We sit towards the back, and I gaze outside. “Yokosuka.”

“I want to go shopping,” Emi says, quite out of the blue.

“Shall we get off, then?”

“But we only just got on.”

The sky grows an ever-deeper blue; it’s almost too exquisite to watch. I gaze out the window, eyes glued to the view. The sides of the buildings lit by the sinking sun all glow a uniform gold, subtle yet intense. It’s as if rectangular shapes have been cut out of the sky, revealing this shining layer beneath.

“I didn’t know the city could look like this.”

I feel something drop onto the back of my hand. Tears! Shocked, I turn to face Emi.

“This is the first time I’ve cried over a little scenery.”

“It seems like everyone starts being honest with themselves about their feelings, once they come here.” She takes a tissue from her pocket and puts it to my nose. “Well, it’s different for the workers, of course.”

She seems troubled. I blow my nose. Come to think of it, this must be the first time since I was a child that I’ve cried in front of another person.

It seems like everyone starts being honest with themselves about their feelings, once they come here

“Apparently there’s something in the air here that gets you all wistful and nostalgic. Hey, are you glad you came?”

“Of course I am!” I answer, ardently.

I haven’t told Emi about this yet, but I had absolutely no friends before this year. It was a serious problem—and not one that could be easily explained away by shyness or introversion. I did have an idea of why people didn’t like me, but I just wasn’t prepared to admit it. I consoled myself by deciding that I hated other people and had no desire to love anyone.

But I’m drawn to Emi now, after only meeting her a couple of times. And there’s Naoshi, too.

“We shopping, then?”

“Oh, right.”

“Let’s get off here.”

And the magic doesn’t wear off, even after we leave the bus. It’s actually painful how beautiful even the ground is, and how the air is laced with the sweet scents of spring.

The last of the sunlight gives an even coat to the tops of the buildings. I can see the start of Chinatown a little down the road.

“Ages ago, I used to go out with this boy from Hong Kong. What was his name? Law, something like that.” Whose words are these coming out of my mouth? There’s no way that could’ve happened to me. On Earth, all I did every day was trudge back and forth between class and home. Are these someone else’s memories?

“What was he like?”

“Good at looking after money, but I don’t mean he was a cheapskate! He was very orderly. And extremely romantic.”

“Hmm, well. Bet he was a pretty randy bastard then, wasn’t he? Often the case with those outwardly rigid types.” Emi never ceases to impress me with her insight.

“Yeah, he was! Feels like an age ago now, though.”

“Bet he was always posing, right? And almost too protective.”

“Uh . . . Well, he didn’t love me much, so I never had the benefit of any protection like that.”

And it was aged twenty-four that I lost myself to Law’s almond eyes . . . Just when did I take over someone else’s life?

We’ve arrived at an area lined with brash American-style boutiques.

“You know, I was hoping for something grungier.”

“How about those punky places over there, then?”

I buy a stole made of yellow netting and a rose to wear around my neck. Still not quite there. Then, a black suit from a less racy shop—with a tight skirt, mind, not trousers.

“Want to come round to mine for dinner?” Now, I’m only inviting Emi over because I hate being alone with CHAIR. This is a chair that sits in the middle of my apartment and talks to me—and only ever to say mean things! It’s pretty ridiculous for a piece of furniture to have a personality, but that’s just how it is. And it talks just like my mother.

“I’m kind of tired. It’s been an intense day. I want to take a break and digest it all, by myself.”

The fact is I’ve had my fill of her already, so I’m secretly quite glad. But where’s my sense of agency? It makes me sick, seeing myself so limp-willed.

Emi raises her hand in the darkening blue light, and I sigh as she turns and walks away, as though the words “free will” were written across her back.

Once I get home, I take tonight’s clothes out of my wardrobe and lay them on the bed.

I sit down beside them and light a cigarette, and CHAIR pipes up. “What about the new outfit?”

“Oh, the black one?” I lay out the black suit, too.

“Why did you go and buy that?” She has a rough, raspy voice, husky yet piercing—she sounds just like my mother, and I hate it.

“I thought maybe Naoshi could be into plain girls. And it makes a statement, doesn’t it?”

“Do you know why you’ve become so obsessed with that boy without even having spoken to him yet, by the way?”

“Because he’s bloody gorgeous, right.”

“Wrong!” CHAIR gives an evil cackle. “You already know him, child.”

She shakes with laughter, her balding velvet cover trembling with its greyish floral pattern, and her armrests wobbling, too.

Now, I’ve never sat on this CHAIR—she started jabbering away at me the day I took this room. Anyway, you can tell her springs are probably broken just by looking at her.

“Look, Naoshi is someone you used to know. That much is true.” She takes a few steps to the side.

“Why did I forget him, then?”

“Because your long string of failures begins when things start going to pot with him. It takes you a whole decade to even realize he’s serious about you.”

“Does he dump me?”

“No, child.” CHAIR strides about the room.

“So . . . You mean there’s some misunderstanding between us and we split up. Is that it? I mean, there’s no way I’d be the one to leave him.”

“What if you are?” She lets out a snigger.

“No, I’d never—”

“Oh, come on, I just wanted to scare you a bit!”

“But, look—that’s not something that happens to this ‘me,’ here, right? It’s not me that makes that mistake.”

“Well, I suppose we could say so,” CHAIR says with a speculative air, before shimmying back to her original spot.

“That’s something done by another ‘me,’ in a parallel world, right? How old am I there now?”

I realize it’s a stupid question as soon as I’ve said it. Which “now?” How do you even define that?

“You’re in your thirties, probably. You’ve realized your mistakes and you’re stuck in a whirlpool of despair. You’re in a state, like that last song you put on at the Seaside Club. Seems like you’ve actually gone a bit mad.”

“Oh, cheers.”

“No need to thank me, dear.”

“I seem to be wrong in the head here, too.”

“How come?”

“I mean, a chair’s talking to me.”

“You get doors and microwaves that talk, don’t you?”

“That’s because someone’s made them that way!” It’s gone seven o’clock.

Cooking can be a pain when I’m on my own. (CHAIR doesn’t eat anything, you see.) And my diet is horrific. I suppose I hate fresh fruit and veg because my mum was always telling me to get my five-a-day in. She’d always be saying, “It’s good for your looks. Ugly girls need all the help they can get!”

So, three pieces of stale cake it is—straight in my gob.

“Aren’t you going out?” She knows everything.

I take a bath, which makes me sleepy. I put my pajamas on and lie in bed. The clock by my bedside reads a little before eight.

“Get dressed, do your make-up!”

“I’m shattered. Be quiet for a bit.”

“You’re scared, aren’t you? That’s what it’s really about. You’re worried you’ll mess it up again.” I hear mockery in her voice.

“Sure, maybe. But why did it happen before?”

“Because you had no self-confidence. Naoshi’s always surrounded by girls, looking bored, right? And you were just too damn proud to let anyone know how that made you feel. You hid it from him. Never even occurred to you that he might doubt himself too.”

“What did you say?” I ask, leaping up.

I’d heard CHAIR’s words, though—we both know that. So she says nothing more.

It’s way past eight o’clock.

Emi must’ve left by now. I consider calling her . . . But only consider. I don’t actually do it.

“How long are you planning on staying on this planet?” asks CHAIR after about half an hour has passed.

“I want to stay here forever.”

“Everyone says that, dear. But you can’t, can you? You have to live your life. You have to cook, clean, look after the kids when they’re sick. You have to go out to work.”

“Why do I have to keep on living that life?”

“Well, I’m not sure why.” Her voice strikes a gentler chord, all of a sudden.

And I repeat that phrase in my head. “I’m not sure why.” I fluff my pillow, turn off the lights, and chant a spell. Sleep, sleep. Make the world disappear.

Two days later, and I’ve made it to Friday’s Angels. “Heroin” is playing, which is a major plus—but no sign of Naoshi.

“Apparently he was just here,” Emi yells. You have to shout to be heard. “He came in with that girl there,” she says, pointing to a blonde dancing centre stage. A different girl to the one he was with at the spaceport.

I go to the bar and order a 7Up.

There’s a strobe light pulsing, and people’s movements skip between each flicker. It could be a time-lapse video, with a fresh troupe of frozen corpses searing every flash-lit frame.

The lighting becomes more psychedelic. I cut through the middle of the dance floor (keen to get a good look at this blonde) and make for the door. Not particularly pretty. (Not that I’m particularly pretty, either.)

Naoshi’s there, sitting on the stairs.

“Aren’t you coming inside?” I ask, standing still.

He keeps his head down and says something back. I don’t hear him.

“What?”

He repeats himself, but the sound coming from inside the club swallows his words, and I can’t make out what he’s saying.

I sit down beside him. He’s repeating, I think, the same words again, and with great patience.

“This girl said she wanted to come, so along I came . . . But I just hate people looking at me.”

I say nothing.

Apparently he came to this planet around the same time Emi did, whenever that was. And he’s famous, so I knew his name straight away.

He cuts a very striking figure and there’s a distinct aura about him. Some would say he has a sort of ethereal beauty, and you can’t help but know he’s only half human.

He was one of the first alien “blends” and, well, his almost completely green head of hair is hard to overlook.

Expressionless and gloomy, he has these severe, empty eyes that seem to say he’s long given up on any kind of hope or ambition.

I take a sip from my bottle and pass it to him. He looks back at me with that wide, unsettling stare—it’s like looking into the glass eyes of a creepy doll. His eyebrows are also a deep green and bushy around the sockets.

Meekly, he sips the 7Up.

“I don’t get it. Girls always want to come to these crowded places. I just wanted us to be alone together, somewhere quiet.”

“Well, it’s because they want to show you off.”

He runs his long fingers through his hair.

I can hear some popular song playing through the door. The dry superficial performance sounds pretty funny to me now. The melody is so monotonous, and the phrases are excessively long. Grand old golden-ratio tunes just don’t seem to suit this era.

“You know, lately,” I begin, slowly, “I’m finding it hard to identify what happiness and pleasure are.”

He looks up.

“Well . . . Does it matter? If something feels good, that’s pleasure.” He gives a weak laugh. “Nothing more to it.”

“Seems like you live a pretty straightforward life.”

“Oh, I’ve got my problems. You know, I used to comb over and pick apart every single day. Then, all of a sudden, I stopped thinking—I became ill . . . My brain cells took some damage, and I lost the ability to, I dunno, think like I used to.”

It’s as if he’s talking about someone else entirely. “What do you mean, you’re ill?”

“I’m a drug addict.”

He looks up at me after giving this blunt answer, trying to gauge my reaction. I fight the muscles in my face, trying to keep from expressing anything.

He gets up.

I follow his line of sight to find a boy standing at the bottom of the stairs, seemingly fixed to the spot, looking like a glitch in the scene. He’s an absolute fashion victim, with a bandana tied around his calf. Brilliant. Doesn’t suit him at all, sadly.

The boy makes his careful way up the stairs, step by step. He’s smaller than Naoshi height-wise, but sure makes up for it in width. One of those baby gym-rat types.

“Need to have a word with you, pal,” the boy says, with a cracked voice.

Here we go, I think to myself.

“I don’t think I know you,” Naoshi says, apparently racking his brains.

“About the girl.” He glares at me. “Her, there.”

“Sorry, what?” I step closer.

“Don’t be moving on other people’s girls, you hear me?” He looks at us both.

“Since when am I your girl?”

“Look, there’s no sense in pretending. We met twice before, out there, and you made them moves on me, remember? ‘The world’s gonna end soon,’ you were saying. ‘Let’s watch it go, together.’ And I’ve been preparing for it! But here you are, spilling all the fucking beans to this one.”

“He’s a nutcase!” I say.

Naoshi lets out a long sigh. “Everyone’s messed up here.” The boy tries to grab my arm.

He falls down the stairs. Naoshi yells something. The boy hits the landing hard.

Seems I’d kicked him over with my very own boot. I say “seems,” because my body moved before I’d even thought about it. I stand very still, surprised by my own actions. “Is he knocked out?”

Naoshi is intolerably calm. “It’s fine. He didn’t hit his head.” The boy gets up, clumsily, trying to recover his dignity.

Emi comes out through the door. “Fancy getting something to eat? Oh, dear. That blonde girl’s looking for you, you know.” Naoshi makes to leave, but pauses and asks me, timidly,

“Mind if I come see you tomorrow?”

“What time?”

“Just after noon.” And he heads indoors before I can even nod my head.

I lean against the wall. “I wish he’d stop this.”

“The fighting?”

“No, no, that was me. That’s not what I mean.”

“You’re shaking.” Emi gives me a hug.

I open my mouth to say something, but close it again.

“Let’s go.” She leads us out, and as we approach the landing, the muscly boy is still there, staring dumbly at me.

Cloud covers the night sky.

We walk along, blown by a warm and balmy breeze.

Wide streets, dark buildings—now and then, a peaceful haze will soften the neon lights of the drive-ins and the nightclub doors.

“Doesn’t this town make you feel all nostalgic?” Emi voices what I’d been thinking.

“You know, I’d always assumed I just wasn’t capable of seeing myself with real emotional clarity.”

“Well, without that clarity, you’ll never make it to the big leagues. You’ll just spend your whole life stuck among the amateurs.”

We cross the bridge. Chains of boats line the river. The road by the edge seems to be part of some big construction project, with cranes overhead casting their dinosaur-shaped shadows. The lights of cars following the curves of a distant motorway are joined like a necklace.

A desolate scene, quite apart from the seafront. Yet I still feel a similar sense of nostalgia.

“But recently, you know, I’ve been having these moments of shining coherence. I really mean it.”

“So until now you’ve just been laying on emotion for show when you’re with other people?”

“I suppose so. Hey, how about that place over there with the orange curtains?”

It’s an all-night cafe with poky windows, a cheap air and a sparse scattering of customers.

Emi and I sit at a table by the wall, and a waiter approaches with a lengthy menu. Can’t be bothered with that, so we just go for the set meal and drink.

“What’ve you been seeing so clearly now, then? People say all sorts of things, don’t they, like: ‘I’m turning into my mother,’ or ‘I’m really feeding the weak woman stereotype.’”

“There’s not much difference really, is there?” Emi’s mouth creases into a smile. “Everyone thinks they’re unique when they have these moments of clarity. Kind of like how you felt when you cried in Yokohama, perhaps. I don’t know. I find those moments allow me to forgive myself, even if it’s just a little bit . . . And I forgive my mother, too.”

“Things gets easier once you acknowledge the situation.”

“That’s right. Even if you don’t solve anything. It’s the same with my own illness, too. It might flare up again once I’ve gone back to my life on Earth. It might not. There’s no controlling that. It’s not a good habit, to want to solve everything.” Emi gazes elsewhere as she speaks.

My meal arrives. There’s the main dish, a salad, and also a small glass of rosé.

“Is this included? It wasn’t on the menu.”

Emi wraps her handkerchief around her finger. Before long, her order comes too. And, sure enough, another glass of wine. “They’re really testing me.” The handkerchief, tied like a rope, turns her finger white.

“Come on, it’s fine—” I begin, only to be shocked by Emi’s intense glare, seething with energy. I thought her gaze would pierce right through the glass. She looks away and wraps the handkerchief tighter, until it hurts. Her hands are shaking.

“Hang on, was that . . .”

She looks up. Resentment wells in her eyes and spills out with her tears. “That’s right. The stuff about my mum—that’s me. And no, I didn’t mean to lie about it. I just couldn’t acknowledge that part of myself. It was too painful, so it had to be smuggled in under the guise of my “mother.” They put us to sleep before we came to this planet, right? They must’ve manipulated our minds along the way, somehow.”

I stand up, shuffle round the table, and sit down next to Emi. Though they’re both types of addict, there’s a stark difference between an alcoholic and a dope fiend. The boozer clearly needs other people. They’re clingier than junkies. Now, if you’re hooked on tranquilizers or painkillers, you may be less bother because you become so passive, but you’ll inevitably be cold, distant and unfeeling.

But how do I know all this? Emi continues sobbing.

“You know, I’m not sad at all. I did just realize that this alcoholic mother of mine is me. But these tears, they aren’t because I’m sad.”

I grab my bag and pull out a handkerchief. Emi uses her own to blow her nose, then thanks me and reaches for the new one.

“Do you mind?”

“Not at all.”

Her tears subside. She dabs at her eyes and tries hard to smile. “Feels good to cry.”

“Yeah.”

“I’m going back to Earth tomorrow. That’s my illness: I’m an alcoholic. I think I’ll make it through.”

“Wait, hold on! Tomorrow, that’s—”

“The sooner the better. Let the Seaside Club barman know, will you? He’s been a great help.”

I’ve come to depend quite heavily on Emi, so I feel a bit dejected. She knows what I’m like. You end up completely hooked on people who indulge you. Naoshi, though—he hardly seems the dependable type.

“We’ll meet again, I know it.”

I listen to her words, crestfallen. I stare at those glasses of wine, as if they harbored destiny itself.

I can’t have slept more than a few minutes before a faint knock wakes me up.

“The sun’s barely up, you know,” whispers CHAIR.

I go to the door in my pajamas, barefoot. There’s no intercom. And there stands Naoshi. He stretches his long neck, his hair covering his eyes. “I thought you might be out,” he smiles faintly, with his big lips.

“Why?”

“’Cause it’s so early in the morning.”

I really don’t see his point. He smiles again. It’s a bit of a grimace, actually—he seems slightly unhinged. Exhausted, too.

“Come in.”

He moves to the sofa.

“How did you know where I live?”

“I just ran into Emi. She had a suitcase with her. Pretty thing.”

“Have you been up all night?”

“Don’t worry, I’ll go home soon.”

“Do you want tea or coffee? I’ve got jasmine tea, too.”

He lays on the sofa, his eyes on my bare legs. Then, a moment later: “Coffee’s not very good for you, you know.”

“Says the drug addict.” I put the kettle on.

This isn’t about ‘redoing things.’ There’s no starting over.

“I’m sick of these reboots,” he murmurs, facing me, as I open the can of jasmine tea. “I’ve had so many already, redoing things over and over again.” I can see only his green hair from the kitchen. “This is maybe my fourth time coming here.”

I take the mugs out of the cupboard.

“Correct,” announces CHAIR.

I almost drop the mugs.

“This isn’t about ‘redoing things.’ There’s no starting over,” she says. “You go through some similar experiences every time—it’s about letting go, basically.”

I cower at CHAIR’s shrill voice, but Naoshi doesn’t seem bothered by it at all.

I quiver as I make the tea.

“Reboots are about letting go, and accepting things,” CHAIR emphasizes, more quietly.

Naoshi opens those cold, unsettling eyes and watches me settle his mug on the table. He sits up and lets out a sigh long enough to carry his whole soul.

“You’re growing on me,” he says offhand, with a shrug of his thick eyebrows, “I’ve come to like you now, having met you so many times here on this planet.”

“Here he goes, blabbing on again.” More mockery from CHAIR.

“It’s simple really. So this is my fourth reboot. Now, for some reason you didn’t turn up on my third—I guess they try mix it up a bit.” I don’t think he can hear my speaking furniture. “Well, it’s made me believe in fate anyway. I always end up the same no matter what path I take.”

“Can you time-travel, is that what you’re on about?”

“Nope.” He shakes his head.

I sit on the bed, drinking my tea.

“And if you really think about it,” Naoshi says to himself, “it’s not so bad.”

“No thinking needed,” quips CHAIR.

“You know,” I say, “I thought you’d be more introverted, a man of fewer words.”

“I am, when I’m out there. And I’m pretty loaded right now, too.”

I get up and sit by his feet. “Hey, what exactly are these ‘reboots’ all about?”

“It’ll become clear, soon enough,” he replies quietly, sounding a little weary.

“Now then, look at this old scene,” CHAIR begins, “you’re hoping to get him to say he likes you again, aren’t you? But you needn’t bother. He could say it a hundred times and you’d still never be satisfied. Not even a thousand times would work. And it’s because, child, you just don’t love him. Not one bit!”

The nerve of this CHAIR, using a word like “love”? Has she no shame?

All the same, I get my sweet and coy act on (tilting my head to one side, etc.) and ask him, “What’s love?”

“This, surely?” He reaches out and places his hand on my shorts, on my crotch, before immediately taking it away again. He did it so casually I couldn’t even jump. “I’m a horribly direct guy, aren’t I?”

Oh, but if I showed some force, he’d bend to my will. You see, Naoshi had long ago disembarked from his life, had withdrawn and shut himself away in this pillowy narcosis. And now, he’s merely watching himself drift on—watching, wholly numbed, and without emotion. I doubt he could even muster the energy to try and understand anyone else. In that head of his, there probably isn’t much difference between me and his old guitar. And he isn’t trying to hurt anyone—no, not at all. He’s just . . . checked out.

But who cares if he objectifies us? It’s all fine with me. “Well, he’s not exactly ‘fine,’” CHAIR says, in my head.

I want to make him mine.

“And you reckon you’ll bring an end to your endless string of failures that way?”

I know, I know. But the reason I want him is something more urgent than love.

To me, you see, Naoshi is . . . a symbol of a certain time. And the voice in my head is no longer CHAIR’s. A make-believe time. I made it up, all by myself.

“Mind if I stay here a bit longer?” He seems more relaxed all of a sudden. And then I remember. He asked the same thing before. Back when I was twenty years old. An endless age had passed since then.

“Why don’t you sleep in the bed?”

“Okay.” He begins taking off his clothes.

I open the curtains slightly to look outside. A new day—fresh, luminous—is already starting. I imagine I’ll head back to Earth eventually. Once I manage to let go completely. I no longer care about happiness or unhappiness. I just hope the scenery’s pretty, wherever I am.

“Aren’t you going to lie down, too?” Naoshi calls out to me from the bed. I lift up the covers and get in beside him.

He wraps his arms around my neck. And he speaks now, in a gentle voice, to no one in particular. “Don’t worry. The world won’t stop spinning. It’ll keep going, even if you don’t want it to. On and on, until you’re absolutely sick of it.”

The barman from the Seaside Club is staring into my eyes when I wake up.

“How’re you feeling?”

“Not too bad.”

He’s a doctor, and we’re on Earth.

“You didn’t get what you were looking for, though.”

What a serious look on his face!

“I’ve come to accept that it just might not be possible.”

I can see a dull-colored sky through an open curtain. Weak sunlight is coming through the window.

“That planet isn’t real, is it?”

“That’s correct. Everything you experience there has been programmed and transmitted to your brain. We didn’t want to create a fantasy world, you know, where everything’s just as the patient wants it.”

“What if they never want to come back?”

“We forcefully wake them up, which can be quite painful, psychologically.”

“And the travelers with silver bracelets were all patients, weren’t they? So everyone else must’ve been fabricated, imagined . . .”

“Emi, who we discharged a little earlier—she left her contact details. Seems she wants to meet up with you.”

She must be thirty-six years old, in this world. Naoshi must be out of the facility too, then. He took off from that planet three days earlier.

I get up.

No need to look in a mirror. I already know the score: I’m a dejected housewife, in my thirties—impatient and frustrated, yet too limp and lethargic to do anything about it. And I live in one of those hideous, uniform, low-rent apartments I can see out the window.

The doctor has left.

I change into my clothes.

Waiting for me in the corridor is my husband.

Naoshi’s grown so shabby and unsightly, a goblin next to his past self. Silently, he steps towards me.

I take his hand, for the first time in forever. “Please, let’s not go to that planet anymore. Do you realize what these reboots are doing to us?”

He issues some vague sounds in response. And outside, the day turns to a swampy night.