Lit Mags

Humans Are the Most Alien Creatures

An excerpt from BEAUTYLAND by Marie-Helene Bertino, recommended by Thomas Morris

Introduction by Thomas Morris

A hundred pages into Marie-Helene’s Bertino gorgeous third novel, Beautyland, the mother of our protagonist Adina says to her:

Do you know, there are people who when they ride in cars, only ride in cars? They don’t point things out to make the other person laugh, they don’t joke around or say anything interesting. They sit there. If they say anything it’s like “Make a left at the Burger King.” They don’t even joke about things like The Flying Man. It wouldn’t occur to them. They sit there, driving in cars. Throughout every area of their lives. They work a job, have dinner. No humor. It’s called being a literalist and most people are one. I’m glad you’re not one.

And this reader is also glad.

Because in Beautyland—surely one of the most charming novels I’ve ever read—Adina is our alien guide, wiping the windshield with her sleeve until we’re able to see the roads of experience in ways we’ve never before perceived. The daughter of a working-class single mother, Adina probably believes, at some deep level, that if she stops joking around, then their battered and heatless VW may well break down. Likewise, if she were to stop compiling and sending her observations about life on Earth to her celestial superiors via the mysterious fax machine that she acquires at the end of this excerpt—well, perhaps the fabric of her whole universe will fall apart.

This is a novel of scrupulous, hilarious, and loving observation. It’s also a novel about observation—about seeing and wanting to be seen, and how the act of observing can change the observer. As Adina watches the people around her, carefully studying what makes them tick, the novel reveals the countless pressures (tacit and explicit) that operate on someone as they attempt to become themselves. With the lightest of touches, Bertino decodes how these messages can be shaped by one’s social class, gender, and ethnicity—and mediated and buttressed through the education system, one’s peers, and the media. All the while, her illuminating prose beats and glows like a sky of dancing stars.

I’m writing this short note from Ireland, where I had the privilege of becoming friends with Marie-Helene when she lived in Cork for a few months in 2017. In the six years since, whenever I’ve felt lost, lonely, confused, or desirous of being somewhere else, I have picked up the phone and called Marie, and we have talked for hours. She makes me laugh like no one else on Earth, and I find her honesty, her integrity, and her love of people—all qualities abundant in her work—deeply inspiring. Talking to Marie and reading her fiction, I’m reminded that life can be difficult and sad and funny and beautiful, often all at the same time.

And speaking of Time: on this planet, in these finite human lives, Marie-Helene Bertino’s own time, for all its magic, is still a limited resource. I know she can’t answer all calls, at all hours. What good fortune, then, that you and I will always have her books—these strange and perfect missives that are sent here to assure us: we are not alone.

– Thomas Morris

Author of Open Up

Humans Are the Most Alien Creatures

Marie-Helene Bertino

Share article

An excerpt from Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino

In the beginning there is Adina and her Earth mother. Adina (in utero), listening to the advancing yeses of her mother’s heart and her mother in the labor room, vitals plunging. Binary stars. Adina, swaying in zero gravity. Térèse, fastened to the operating table. The monitor above the bed reports on their connected hearts: beating heart, heart, beating heart, beating. Térèse’s blood pressure plummets as Adina advances through the birth canal; she has almost reached Earth. At this moment, Voyager 1 spacecraft launches in Florida, containing a phonograph record of sounds intended to explain human life to intelligent extraterrestrials.

It is September 1977 and Americans are obsessed with Star Wars, a civil war movie set in space. Bounding to the stage after hearing her name, a Price Is Right contestant loses her tube top and reveals herself to a shocked Burbank audience. In the labor room of Northeast Philadelphia Regional, no one notices Térèse’s plummeting blood pressure. Something lighter and more conscious detaches and slips beneath the body on the table, underneath the floor and sediment, landing in a corridor of waist-deep water. Behind her, unembodied darkness. Far in front, over an expanse of churning waves, a certain, cherishing light. Térèse wants the light more than she wants health, more than she wants this baby’s father to become a shape that can hold a family. She forces one leg through the water then the other, trying to paddle herself like a vessel.

The contents of Voyager 1’s record were chosen by Carl Sagan, a polarizing astronomer who wears natty turtleneck-blazer combos and has been denied Harvard tenure for being too Hollywood. Carl and his team have assembled over a hundred images depicting what they decided were typical Earth scenes: a woman holding groceries, an insect on a leaf. The sounds include Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode,” the sorrowful cries of humpback whales, and recordings of the brain waves of Carl’s third wife. Footsteps, heartbeats, and laughter. Destination-less, Voyager 1 will travel 1.6 light-years: farther than any human-made object. At a press conference Carl says that launching this bottle into the cosmic ocean is intended to tell “the human story.”

The astronomers hoped to include the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun,” but Columbia Records asked for too much money. It’s hard to make human beings believe in things.

Also not included is 1977’s top hit “Barracuda,” though every story hummed that year over the upholstered dividers of United States of America or yelled between cars pinned atop Auto World pistons or delivered through the eldritch mists of Beautyland’s perfume section is told over the twinned guitars of the two-sister band from Chicago. It plays on the radio in the nurses’ station at Northeast Regional. A speck of Panasonic rustle between songs.

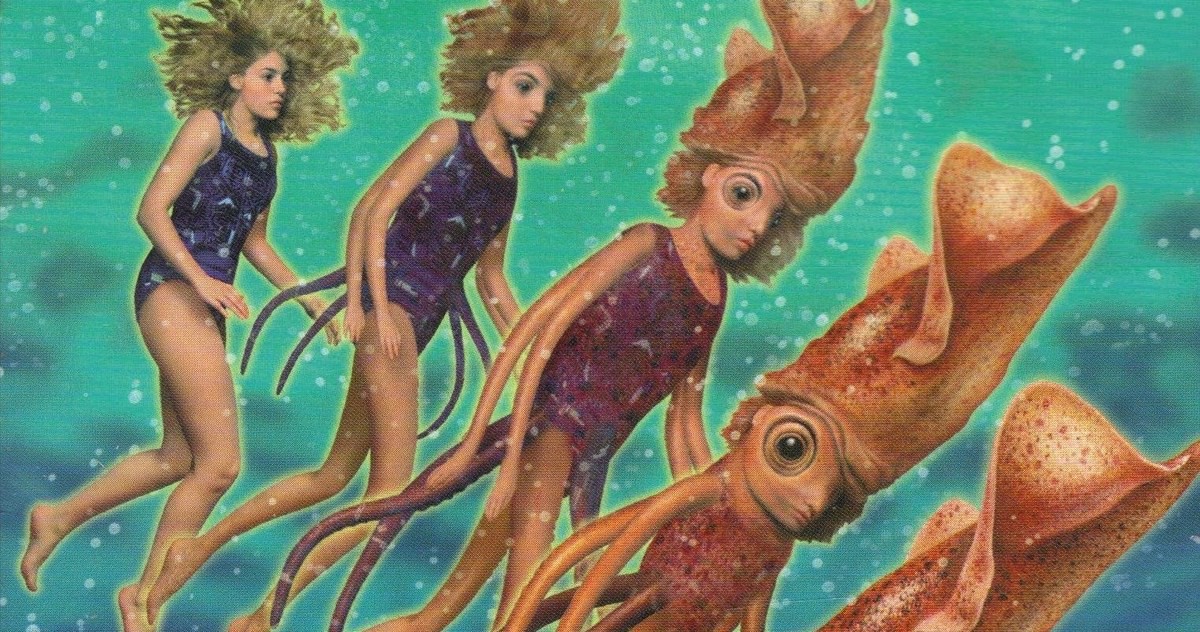

The current is too strong; Térèse makes no progress. The light remains distant. She cries out. The fright of a huge suck pulls Adina through to big white. Térèse regains consciousness under unfriendly lamps, baby on her naked chest. The baby is too small. Her skin and eyes appear lightly coated in egg. She is placed under a phototherapy lamp. Lit blue-green by the mothering light, yearning toward its heat, she appears other than human. Plant or marine life, maybe. An orchid or otter. A shrimp.

Adina: noble

Giorno: day

Térèse watches through the nursery window as her new daughter fails to reach the light.

Adina will hear this story several times in her life and in her imagination Térèse will wear a strapless red corset and capelet like Ann Wilson on the cover of Little Queen, only Sicilian, and with roller skates, humid late-season wind blowing through the doors. Her hair will glisten darkly with Moroccan oil, too coarse to relent to the popular feathering style.

She is too tired to realize that pursuing him is following the promise of a dead star.

In reality, Térèse has been arranged into a wheelchair by the nurses, feeling retracted to Earth by an unkind thread. The collar of her hospital gown falls beneath her collarbone. Her baby unrolls a tiny fist and she thinks of her unchained friends, Adina’s father among them, on their way to the club. She is too tired to realize that pursuing him is following the promise of a dead star. The nurses chat about the Price Is Right contestant. Did it on purpose, one says. The first part of Térèse’s life is over. He will never again beg to hold her perfect nipple in his mouth. She will never again be wild Térèse dancing on the lit floor at Bob and Barbara’s. Her parents will not support her. She is this tiny baby’s mother, mother, mother. The she in Adina’s head.

In Adina’s imagination, her mother will gaze through the nursery window, electric guitar chevroning behind her. In reality, Térèse is perforated by exhaustion, parentless, barely returned from death’s corridor. Even the hospital gown refuses to help; its foolish smile exposes half a perfect breast.

But the womb is Adina’s second lost home. The first has already tumbled three hundred thousand years away. A planet in the approximate vicinity of the bright star Vega, in the northern constellation of Lyra. Intelligent extraterrestrials have sent their own probe in a form and to a location no academic—not even Carl Sagan—could anticipate.

It is an interstellar crisscross applesauce. Two celestially significant events occurring simultaneously: The departure of Voyager 1 and the arrival of Adina Giorno, early and yellowed like old newspaper. If like a newspaper Voyager intends to bring the news, this baby is meant to collect it, though no one knows that yet, including her. Even as the spacecraft breaches the troposphere, the delicate probe stretches her fist toward a heat lamp in the pediatric ward of Northeast Regional, having just been born—or landed—depending on perspective, premature. Wriggling, yearning, recovering in heat, full head of thick black hair, at the moment she is still mostly salt and feeling.

This family, trying, lives across from Auto World in Northeast Philadelphia. Their apartment comprises the bottom floor of a two-unit brick building attached to another brick building, attached to another brick building, and so on, et cetera-ing down the highway. These are starter row homes. This is a starter family. The complex’s lawn, newly mowed, emits a pleasant fecund smell to the cars speeding by and to Adina’s father, where he crouches, glaring at a screwdriver. If he keeps his city job they’ll move to the suburbs where within years he will not rent but own an unattached house. They’ll have a yard that’s only theirs, a grill, a tree, and enough space for each family member to do things alone. There is no solo activity in the row home across from Auto World. Being a father is alien to this man but he’s trying. Today, he will use metal to add wood to wood and produce a swing, the way a man plus a woman and baby makes a family.

Each row home is designed like a cadaver lying flat on a table: at the prow of the apartment is an abbreviated entryway that normally holds Adina’s kicked-off boots and her mother’s neatly arranged work pumps, hallway like a throat leading to the open kitchen, the torso a family room big enough to hold a couch and a half-moon table covered in the open faces of their books, a fart of a bathroom, two small back bedrooms. Wood paneling. Everything possible painted beige. In front of Auto World a flying man twists and gyrates, making Adina and her mother giggle as they pull into their driveway.

Four-year-old Adina wakes from a nap and moves through the apartment, surprised to find the family room empty. Where are they? She believes she is the nucleus of every interaction and while she sleeps her parents pray for her to wake. She is still inactivated. She is still upturned to the sun. She cannot stop thinking about the bunnies she saw on the lawn the previous day under a bush, heads pressed together in a soft shamrock.

She believes she is the nucleus of every interaction and while she sleeps her parents pray for her to wake.

There are no cookies in the jar and the fridge is filled with off-limits bottles. Kid math: if her mother is rustling in her bedroom then her father must be in the backyard. There is still as much chance Adina will go to her father as her mother. She pauses. The home itself—every crock on the shelf, every bill—seems to pause.

The swing wins. Adina longs to sit weightless on a piece of oak fastened to rope. The vehicle of upward thrust. There is no reason to have a swing. This makes the swing an anomaly because in addition to its intended purpose every object in the apartment must also function in two or three other ways. Everything repurposed, everything salvaged. Even she, the child, was meant to fulfill several things at once: to be silent, useful, hardworking, a credit to her father.

That morning, her mother pulled a fax machine from a neighbor’s trash and, holding it aloft like a prized marlin, engaged in conversation with herself. “Why would anyone throw this out? Probably because they want the latest model. But it could clearly be a planter!” (Anything about to be trashed was first tried as a planter.) “It even comes with paper!” (She unearthed the roll from the trash, brandishing it in front of herself and Adina.) “I’ll bet it works. Paper! People are crazy.” (People were always crazy.)

Her father said it was ugly and no one he knew had one in their home and it should stay in “the child’s” room.

“Fine,” her mother said in her not-fine voice and carried the fax machine to Adina’s room where it claimed most of her bureau’s top. Except for the paper tray, city-pigeon gray, the machine was the color of the orthopedic shoes the employees wore at her mother’s job. A slim phone posed beside a bank of flat buttons with scripted numbers that glowed when her mother plugged it in. Portals to the business world.

Adina’s mother slid a sheet of paper into the tray. “Who should we fax?”

Adina didn’t know any phone numbers except her own. Her mother dialed: 215-999-1212. The machine whirred to life, trembled pleasantly as it pulled the paper through itself, went silent.

“What happens now?” Adina heard her father in the backyard, readying his tools. The woosh of cars on the street. A clicking sound from a private place inside the machine. A sheet of paper launched from an internal chamber Adina and her mother had not anticipated. An error message: no answer.

Adina’s mother’s eyes were wide. “Incredible.”

It is impossible to be unhappy on a swing. Even at four, Adina knows this. She wants it to be finished so she can be as happy as she needs to be. She wants her father to swing her until she is high enough to reach the porch’s tin ceiling.

“Is it finished, Daddy?”

But some immeasurable slanted expression over breakfast has dug a divot into him. Her mother thinks he’s weak or unable to build a swing. She thinks she’d be better off alone. He is. He is. She would be. Even though the plates are his, the table his, the yard, the everything is provided by him. The nail’s failure to find purchase in the flaccid wood has dug that divot even farther. Now this brown berry kid wants to check his progress? Is he finished. Thank you, how about.

Her father’s neck bulges with veins in an unmatchable shade of red. He pushes Adina out of his space. Maybe he forgets the five concrete steps leading to the shared yard when he pushes her again. The concrete and the trimmed grass offer little to cushion her brief fall. Falls.

In the kitchen her mother lifts a glass of water to her mouth. She drinks eight a day, soundlessly, one after the other. She hears a neighbor call her name and hurries to the backyard where Adina is a quiet lump on the pavement.

How long does Adina stay outside the realm of human voices? Seconds? A century? She wakes to her mother shaking her, screaming go back inside to a constellation of worried neighbors. Earth to Adina. Come in, Adina. Adina reboots. Some things return immediately and some take time. A tin taste sours her mouth. Her mother’s steel grip on her shoulders, helping her stand. Her father’s gaze locked on the abandoned tools on the ground. Adina is activated.

That night, Adina “wakes” in a room designed to appear as a classroom. The English alphabet borders the walls. An aquarium with blinking blue fish and a shelf filled with globes. The scene is stitched from what she has seen from classrooms on television and the visit she made to the grade school she will attend the following year. They are using human objects so she will understand.

Her superiors are an area near the front of the class that shimmers and evokes the sense of the singular plural. Multi- souled, multi-personed Shimmering Area. The closest human word for how they communicate is intuiting. They intuit toward Adina and she receives the message. This is her native tongue. It makes sense that she dreams in it and that using it fills her with ease. She intuits the Shimmering Area is both a location and a doorway.

The lights dim. An ivory screen descends from the top of the chalkboard and fills with projected images. A switchboard operator pulls a line from a connection. Two housewives talk on the phone. A formally dressed man ducks into a telephone booth to make an emergency call. Adina consults the Shimmering Area for whatever is next.

A familiar object flashes onto the screen, the fax machine her mother pulled from the trash. A disembodied hand feeds a sheet of paper with nondescript handwriting into it and presses the large green key. The paper churns through the mechanism. As it emerges on the other side, the machine and paper glow. Joyful sparks beam out.

Adina wakes in her Earth bedroom, nostrils filled with the tang of cleaning supplies. She lazes in and out of sleep, considering a space near the door where morning light has collected into the shape of a ship. Seeing the fax machine on her bureau, she remembers the images from her dream.

She writes on a sheet of paper:

I am an Adina.

After thinking about it, adds:

Yesterday I saw bunnies on the grass.

She feeds her note into the machine and presses the green button. The paper jolts through the tumbler with a robotic scanning sound.

It is so early even the boulevard is silent. Her mother is asleep in her bedroom and Adina is awake in her own, hovering next to an office machine, unsure what to hope for. After a moment, a red light she hadn’t noticed activates. Incoming fax! A sheet of paper squeaks through the tumblers.

DESCRIBE BUNNIES.