essays

Thomas Pynchon Shows Us How White Writers Can Avoid Appropriation

Yes, it’s possible to write about colonialism without being a colonizer yourself

Thomas Pynchon: The name conjures black polo-necked students, carrying copies of Maurice Blanchot’s L’Ecriture du Désastre, chain-smoking gitanes, postmodernism tattooed on their foreheads. The man’s been aestheticized, like his literary movement. But instead beyond brilliant technique, Pynchon should be known as one of the very few foreign (white) writers who wrote responsibly about an African country, and actually improved the world by doing so. He was conscious of his privilege as a white, male author, and used this privilege in order to tell a story buried by white history: the Herero people’s genocide by German colonial forces, the first, “forgotten” genocide of the 20th century.The massacre is integral to two of Pynchon’s most famous novels, V. and Gravity’s Rainbow.

There is a particular set of circumstances that authorized Pynchon’s telling of the event, circumstances which do not exist today. For starters, there weren’t any Herero (or Namibian, for that matter) writers of fiction who had prominently addressed the genocide at the time of his novels. In the ’60s and ’70s there was no internet, nor the masses of scholarship we take for granted. In such circumstances, it was almost a moral imperative to write the genocide down — repeatedly, in Pynchon’s case — to draw attention to it again and again. By doing so, he acted (and still acts, as the books live on) as a kind of ethical megaphone, and ensured that this megaphone would be passed down to others. He led me to Namibian activists and their work, for instance; you should definitely check out what Esther Muinjangue, Israel Kaunatjike and Veraa Katuuo have to say. I also discovered Dorian Haarhoff, a Namibian poet and author, who leads creative writing workshops with local students in order to give their stories a platform.

The story goes that Pynchon stumbled on the genocide while looking for a pamphlet on Malta. He then devoted himself to reading everything he could on it — consulting German reports, anthropological studies, Herero dictionaries, anything. It’s no small feat, considering that V. was published in 1961 and most of the history books on the genocide were written in the 2000s. The Herero massacre wasn’t even really talked about until mid-1990s, since the Namibia was controlled by the South African government — and its apartheid — until then.

Published when Pynchon was 24, V. is an ironic yet heartfelt postmodernist rant against the increasingly corporatized, automated, biopoliticized world of 1961. I was also about 24 when I started reading it, and I thought, okay, this is obviously a very cool book with proper lefty sentiments and a heart and masterful technique and intelligence displayed already by an author no older than myself. I gradually understood that the eponymous V is a time-traveling, shape-shifting woman who embodies the Western, post-enlightenment condition: a terrifying, automated creation, obsessed with jewelry and all specimens of materialism, one that emerges and feeds on Empire and its horrors. It’s fitting, then, that she appears in Namibia in Chapter 9, part of the souvenirs of a German engineer, Kurt Mondaugen.

When I first read V., though, I was taken aback by the sudden change of scene. What is this, I thought, Pynchon’s ‘Out of Africa’ fantasy? I was deeply skeptical about this white man, not to mention tired and afraid. Later that same year, 2016, we would all hear Lionel Shriver’s speech on how the concept of cultural appropriation was just stupid. She praised bestselling author Chris Cleave — white, British — for his “courage” in creating “Little Bee,” a fourteen-year-old Nigerian asylum seeker in his book of the same name. She scoffed at the critics who believe Cleave was wrong to appropriate such a story for himself, because “they are his characters, to be manipulated at his whim, to fulfill whatever purpose he cares to put them to […] It’s his book, and he made her up. The character is his creature, to be exploited up a storm.” It felt like an imperial slap in the face — but it didn’t surprise me. It was an attitude I was already used to, one that’s cropped up many times since then, including recently in Francine Prose’s article for the New York Review of Books. And when V. shifted scenes to Namibia, I assumed it was more of the same. A righteous hippie appropriating a story that wasn’t his to tell: I thought I had Pynchon summed up. When I finished the chapter without outrage, I re-read it, determined that I would find one way that the novelist had failed, had been dismissive, insensitive, crude. I found none. This was incredible to me. As a brown, Créole métisse from the African island of Mauritius, raised on Edward Said, Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire, I’d lost hope that white writers could produce something on us so-called “Others” without me choking on my own bile.

I’d lost hope that white writers could produce something on us so-called ‘Others’ without me choking on my own bile.

And yet, here was a powerful, furious voice on the horrors of German colonialism. Here was a 24-year-old man writing his heart out on a massacre that almost no one had heard of, that nobody was even talking about until decades after novel was published. Here was Pynchon, shedding light on the genocide of the Herero people, and doing so in a responsible, ethical way that didn’t appropriate the Herero voice. It was a revelation.

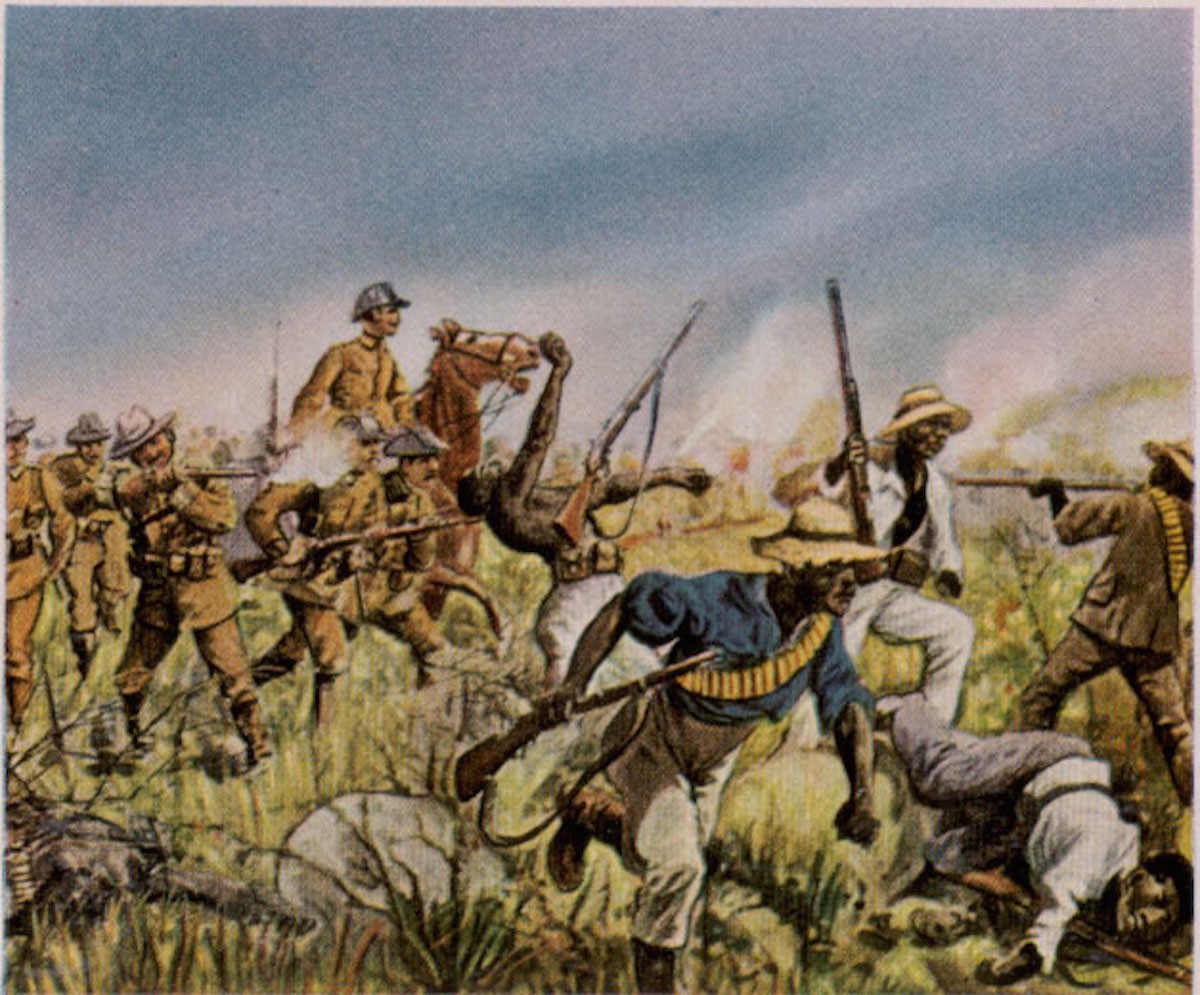

Through faithful historical retelling, Pynchon sears the genocide into our consciousness. In flawlessly lucid prose, he describes how General Lothar von Trotha “issued his ‘Vernichtungs Befehl,’ whereby the German forces were ordered to exterminate systematically every Herero man, woman and child they could find.” You encounter the narrator’s virulent disgust in every line. It’s easy to imagine Pynchon in some dusty archive, tearing through German reports and their blank, statistical language in anguish: “[Von Trotha] was about 80 percent successful. Out of the estimated 80,000 Hereros living in the territory in 1904, an official German census taken seven years later set the Herero population at only 15,130, this being a decrease of 64, 870 […] This is only 1 per cent of six million, but still pretty good.”

You learn about the way the Germans tortured the Hereros, the way they killed them — and you learn it from the point of view of a German character, Kurt Mondaugen. This deliberate choice is part of Pynchon’s responsible storytelling technique: first, it’s one of the only ethical ways of recounting the genocide as a foreign author, since the Herero point of view is not appropriated. The massacre should be told by the Herero people: it is their trauma, their story. Pynchon couldn’t just put words in their mouths, words they didn’t choose. It would have been a third silencing of the tribe: the first being the literal silencing of the people by death, the second the silence of history on the event, and the third, the bleaching of the Herero’s (fictional) voice. Instead, by telling the story slant, Pynchonleaves space for the true voice to come: by leaving the Hereros silent, he acknowledges that an outsider cannot describe a trauma so abysmal in scope. That voice belongs to the Herero people alone.

Second, since you see the genocide unfold through Mondaugen’s eyes, the reader feels like a witness, hands tied and somehow complicit in the mechanisms of white history. Indifference is impossible. The colonists’ actions are told in the same, detached voice as the German reports, a voice that showcases the utter, systemic dehumanization of the Hereros: “From the height of a man on horseback a good rhinoceros sjambok used properly can quiet a n****r in less time and with less trouble than it takes to shoot him […] with the tip of his sjambok, had had the obligatory sport with the black’s genitals, they clubbed him to death with the butts of their rifles and tossed what was left behind a rock for the vultures and flies.”

Gravity’s Rainbow was published twelve years after V. The book is set at the twilight of the Second World War; it moves through time to explore the ideologies and events that caused the war, the genocide, and the Holocaust, and what those ideologies have turned into “today” (the 1970s, but equally applicable today in 2017). In the novel, the Hereros have traversed continents and now find themselves in Germany. There, they grapple with their identities, their displaced condition, the massacre of their people.

We move from V.’s German point of view into the Herero mind. I can’t speak for Pynchon, but I think the reason he gives the Herero tribe a voice now is that we have moved away from the genocide and Namibia into a completely fictional setting and narrative. That doesn’t mean, of course, that the characters should be “used” in any way he wants, as Shriver might say: that would be contrary to everything the author’s strived so hard for. Instead, through his fully-fledged Herero characters — you’ll find no essentialist, indeterminate ‘African’ descriptions here — we learn more about the tribe’s rich history: we are introduced to their culture, language and religion, an account that is well-researched and highly accurate. In this way, the Hereros aren’t seen as faceless victims of a genocide: they are a people, with history, with culture, identity.

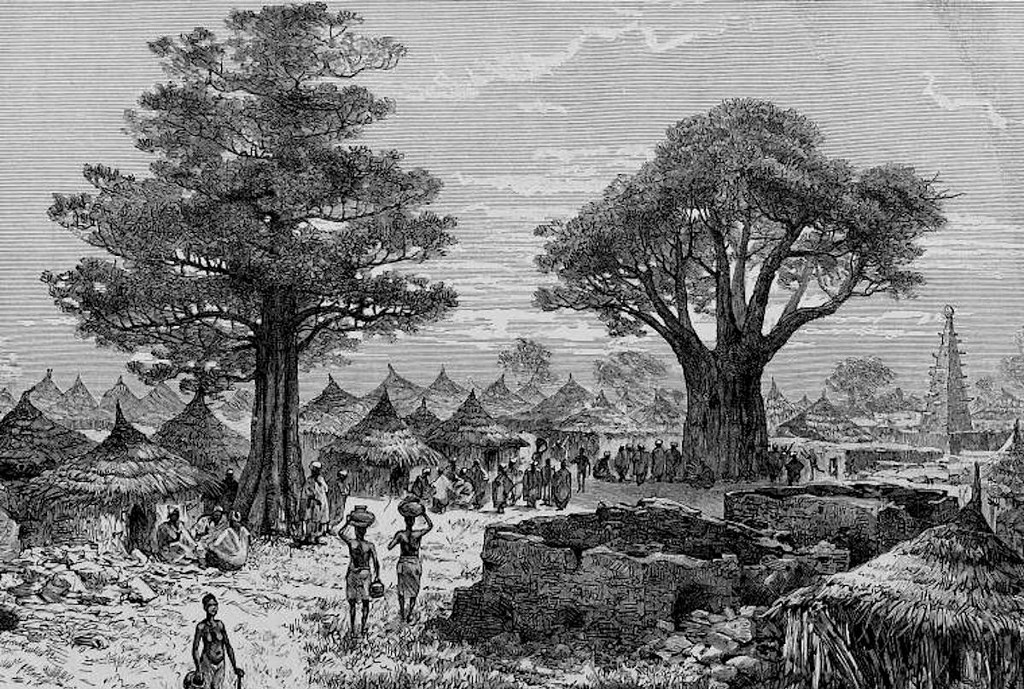

We learn of the Herero God, Ndjambi Karunga, “creator and destroyer, sun and darkness, all sets of opposites brought together, including black and white, male and female.” How the God passes on this duality to Mukuru, the mythical first man, and how he in turn passes it to to the omuhona. How the omuhona carries a leather cord tied in knots, where each knot corresponds to a member of the tribe. How the Herero village is shaped like a mandala. Pynchon gives us a stunning description of the fertility ritual of the Ovatjimba, an outcast tribe of the Herero people: “But as you swung away, who was the woman alone in the earth […] they have pointed her here, to be in touch with Earth’s gift for genesis. The woman feels power flood in through every gate: a river between her thighs, light leaping at the ends of fingers and toes. It is sure and nourishing as sleep.” If the prose of V. was at an ironic remove, in the cold nihilist style of the German reports, here Pynchon leads us on an empathetic journey through fact-based imagination.

I’m assuming that some of you, by now, will be wondering why on earth the Hereros are in Germany. The country should be, and is, anathema to them — so why are they there, working for the Axis powers? This narrative arc, I think, is Pynchon’s way of exploring the shattered, traumatized post-colonial self, without ever rendering his characters into mere metaphor or symbol. I’ll explain by way of Pynchon’s main Herero character, Enzian, who is also the product of incredible amounts of research and postcolonial discourse (I find Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth again and again in him).

“Somewhere, among the wastes of the World, is the key that will bring us back, restore us to our Earth and to our freedom”: Enzian, the leader of the Hereros, relentlessly attempts to make sense of the depthless horror his people have suffered. He was a child when the genocide occurred: “He had been walking only for a few months when his mother took him with her to join Samuel Maherero’s great trek across the Kalahari.” Samuel Maherero was the leader of the Hereros, who understood that he was being played by the German forces for their own gain. He turned against them in 1904, leading his newly united tribes against the colonial powers. The German army decided to exterminate them all; the Herero people fled the troops by crossing the Kalahari desert.

The reader feels like a witness, hands tied and somehow complicit in the mechanisms of white history.

Enzian’s mother dies during the crossing. He is returned to his village, where his people were either exterminated or “used as animals.” “Enzian grew up into a white-occupied world,” Pynchon writes. “Captivity, sudden death, one-way departures were the ordinary things of every day. By the time the question occurred to him, he could find no way to account for his own survival. He could not believe in any process of selection. Ndjambi Karunga and the Christian God were too far away. There was no difference between the behaviour of a god and the operations of pure chance.” He then becomes the protégé of Captain Weissmann (literally, “white man”), who takes him to Europe.

This Herero finds himself at a kind of interstice of identity: violently molded and yet “cared for” by Europe, he is as consequence both attracted to and intensely repulsed by the Western White Man. He carries this rift within himself, since he is both Nguarorerue (“one who has been proven”) and Otyikondo (“half breed”). His memories of how life was before remain blurry, a kind of historical amnesia reconstructed by stories and myth. This is true of all his exiled tribe: the German influence on them has become so strong that it has diluted the Herero sense of self, out there in Europe.

Enzian desperately seeks to make sense of the genocide, of his survival. He is convinced that there is a true text of his people out there, one that would reveal to them their lost identities and their fate, one that would explain their traumatized condition. He was told by Weissmann that he’d find this text by working on the V-2 Rockets. In the face of such devastating power, the power to annihilate masses, Enzian thinks the rocket is a sort of divine manifestation, since it “Begins Infinitely Below The Earth And Goes On Infinitely Back Into The Earth it’s only the peak that we are allowed to see, the break up through the surface, out of the other silent world.” He works on a new rocket, one that would “have no history” and where his people would “find the Center again, the Center without time, the journey without hysteresis, where every departure is a return to the same place, the only place.” A place where the whole Herero self, uncontaminated by colonialism, would lie within reach.

It’s a painful read, to say the least, and I believe it will be painful for anyone whose ancestors were murdered by white colonists, for anyone who is descended from slaves. I’m reminded of my aunts who read Léopold Sédar Senghor and other négritude writers in the ‘60s (and today), working out their identities within the historical amnesia produced by slavery. Of my mother, who prefers not to think about her family’s history, since it hurts too much. Of my grandfather, a Creole man with a Franco-Mauritian father and black, Malagasy mother. He bore his father’s surname, one of the few declared métisse’s of his time. He was made to suffer atrociously for it.

If Pynchon were to set a story anywhere on the African continent today, I would be outraged. African writers — and we are many — ceaselessly strive to put our histories and cultures on the literary map; what we find excruciatingly difficult is to get our writing published and noticed, even when we choose to write in English. Our voice has been cast as niche, all blood-orange sunsets and acacia trees, and moving away from this cliché is formidably challenging, even with the success of authors like Ayobami Adebayo, Akwaeke Emezi, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Chibundu Onuzo (all Nigerian — there’s definitely something special happening in that country).

The threat of a foreign white writer taking my stories away from me is real: take Chris Cleave again. Shriver claims that Cleave told her he “completely sympathize[s] with the people who say I have no right to do this. My only excuse is that I do it well.” He means, undeniably, that he writes the story of a Nigerian girl better than any Nigerian could. By his tone-deafness, by his wilful ignorance, he may very well have stifled the voice of an up-and-coming Nigerian writer who had the same book in mind: she pitches it, she’s told that it’s been done already. It’s easy to understand, then, why I write with dread. I worry about foreign authors. I also worry about second-generation Mauritian writers living abroad, who only know Mauritius through tales, photographs, and one or two family vacations: I worry when they are commissioned to write about Mauritius today. More opportunities lost for us, here. I’ve been told I should move to America or England, get an MFA: there are no such opportunities on my island. An MFA is one of the best ways for us Africans to be legitimized as writers, it’s true — but England’s economy is about to implode, and I’m the wrong color for the Trump administration. Even if I were accepted in a program, how on earth would I emigrate? Our currency is so much weaker. I live with my partner and my cat, loans on our heads. These are my set of problems at the moment: minute, compared to my friends on the continent who have had to flee their countries due to civil war.

The threat of a foreign white writer taking my stories away from me is real.

Besides, the white-dominated publishing industry has political reasons — though it may not acknowledge them — for keeping African writers on the fringe. Though we are, of course, so much more than colonialism and “Western” influence, the more our voices are heard, the greater the rest of the world’s sense of responsibility for what they’ve done and what they continue to do on the continent. Here’s one example: it is not in the American or British military’s interests for the world to know about the forceful displacement of the Chagos people from the Chagos Archipelago (now know as the British Indian Ocean Territory). Once the islanders — referred to as “Tarzans” and “Man Fridays” in military documents — were evicted and forbidden to return, the island was converted into a military base. This occurred as recently as 1967. The base still exists today, crucial to surveillance and attack programmes in the Middle East. Most people don’t know about it, or what happened there. BOMB magazine and The White Review have published Natasha Soobramanien’s fiction pieces on Chagos (Natasha’s an English writer of Mauritian heritage living in Europe, who has beautifully written on the Mauritian immigrant experience), but that’s about it. These pieces form part of her Chagossian novel, a book she’s been working on for many years. It’ll obviously be spectacular, when published: I’ll be counting the amount of reviews she’ll be getting, the kind of conversations she’ll be provoking, in the hopes that her voice won’t be stifled or dismissed. Perhaps it’ll even be a bestseller, fostering Black Lives Matter protests in support of the Chagossians. A Chagos bestseller: an American military nightmare.

Through literature, we can hold people and institutions to account, even when they escape blame outside the pages. V. and Gravity’s Rainbow held the German military responsible for their actions, and helped the world know about the massacre. Real-life justice is less swift. The German government refused to acknowledge its actions and the term “genocide” until 2015, when the president of the German parliament, Nobert Lammert, described the killing of the Herero and Nama people as Voelkermord — literally, “murder of a people” (or genocide). The Namibian people are still waiting for reparations.

What about the would-be Pynchons of today? The justice warriors, sickened by events around the globe, wanting to help but afraid of speaking for the Other? If that’s you, then the greatest thing you can do is help us speak for ourselves, and read our work: be an ethical megaphone. Social media, obviously, provides multiple platforms for you to engage with writers and showcase their work. A Google search will easily tell you all about authors in different, ‘remote’ countries: contact them, and if they write in a foreign tongue, contact their translator or agent. Today’s writers are often hyphenated multi-taskers: writer, editor, editor-in-chief, reviewer. That means, in general, that you’ve got a lot of ways of drawing attention to authors of different communities and places: in the choice of books you review, in the pieces you accept for your literary magazine, even in the way you reject unpolished work by marginalized voices. For those of us without access to creative writing programs, a detailed rejection may be the closest we get to mentorship.

Through literature, we can hold people and institutions to account, even when they escape blame outside the pages.

Or if you want to tell our stories, tell them with us. Take Dave Eggers’ What is the What, published in 2006. It recounts the life of Valentino Achak Deng, a Sudanese refugee, and Eggers and Deng both worked on the novel over many years. Though the book was panned by a few critics — “couldn’t Deng tell his story himself?” — the important thing is, Deng actively wanted to work with Eggers on his story. He wasn’t manipulated or coerced into it. Through McSweeneys, Eggers also published There is a Country, a book that comprises eight pieces written by South Sudanese authors. All of this to say: there are multitudes of ways to help us foreign authors from distant lands, but please don’t write our stories for us: collaborate with us if you must, but otherwise, invest yourself in making sure that we will be heard.

Pynchon did it right, but he did it right for his time. Today, the best way to call attention to something like the Herero genocide would be by standing alongside Namibian authors — or, even better, giving them a leg up and getting out of the way.