Books & Culture

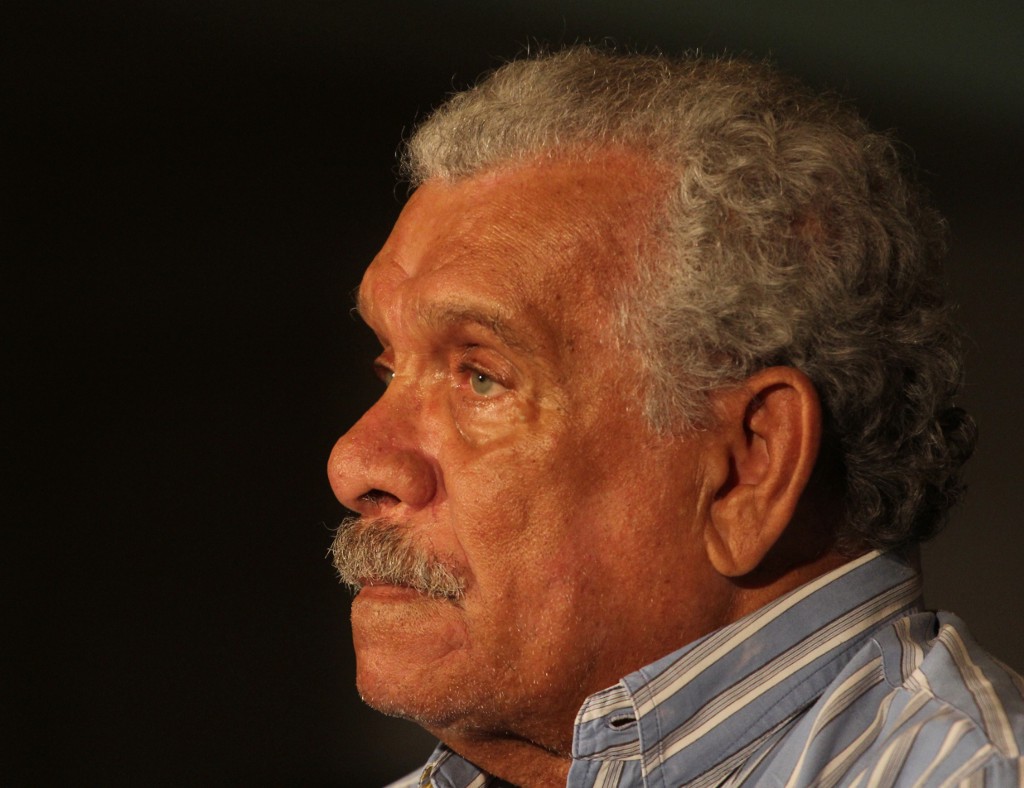

We Need to Talk About Derek Walcott’s Sexual Harassment Scandal

A year after the poet’s death, I’m reckoning with what I know about his life, and how it intersects with mine

I n my final year as an undergraduate student I chose to study the poetry of Derek Walcott for my dissertation. Mauritians of my generation often consider Walcott to be the greatest of all island poets; we’ve adopted him as our own. No-one was ever so articulate in expressing the vicissitudes of our postcolonial selves. When I read him for the first time I remember feeling this intense joy, this peace that no matter what I would write or fail to write, at least I had these poems, these essays that paved the way, that taught me to be proud of being from a ‘remote’ island, and of writing from, for and about that island. I loved how I understood his St. Lucian Créole without a dictionary — it was so similar to ours. I got all the jokes. I felt like he was writing for me, for my hybrid people. I wrote the three famous verses from “The Schooner Flight” on paper and blue-tacked it to my wall:

I had a sound colonial education/ I have Dutch, n****r, and English in me,/ and either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation.

That was me (with some variations in ancestry — African, English, French, Indian).

The same year that I was writing my dissertation, I was sexually harassed by two members of the English department. The first had tried to openly flirt with me before an extra-curricular creative writing class (where he was also a student). I had apologized for any misunderstanding I could have caused and entered the empty classroom; he rushed for me, sat next to me and tried to touch my feet with his without speaking. He was trembling. I thought it was all quite pathetic. I laughed “the event” off the same evening, after having spent an hour locked in a bathroom, making sure he had left the building before I did.

Then there was the professor, who implied one evening that his special interest in me was the reason why I had obtained an incredibly high grade on a paper. He had been my mentor in many ways, an eminence in his field, a confidant, a father-figure far away from home — and roughly the same age as my father, too. It had made me uncomfortable, his way of greeting me by kissing my cheek, but I had dismissed it as an old man’s eccentricity. That evening he told me he would “make sure” I would always be “taken care of.” He offered to drop me home, repeatedly, hoping, presuming sex. I had had the audacity to believe my mind was a gift, one I nurtured by working harder than anyone I knew. He was telling me it meant nothing. He broke me, a little bit.

I went home and cried, and the next day I picked up Omeros — because I still had that dissertation to write, because reading it would bring me back home, because Walcott’s long poem had become the dissertation’s focus. I believed that it encapsulated his best poetry, that it stood as a complete manifesto of his ideas, as it were: the sea and forgetting, the postcolonial nation and its search for identity, the cauterising of History’s wounds. Each verse was song; I’d go read them again and again and each time new meanings, references would emerge, I’d discover the precise music he’d created in the composition of his diction, I’d tap my fingers as he must have done to the rhythm that he seemed to have conjured straight from a Platonic form.

The poem now unravelled and I clung onto the beauty as firmly as I could, since it was the only thing that kept me reading. It was clear now, clear as anything, the lacunae in Walcott’s work. I remembered how the professor was friends with the poet; numerous literary conversations, a trip to St. Lucia. I understood. They were both brilliant. They both looked at women the same way.

Walcott’s women in Omeros are described almost purely in terms of their bodies. The journey to understand one’s identity, to grow, to heal — the Homeric epic of the self belongs to his men alone.

Walcott’s women in Omeros are described almost purely in terms of their bodies. The journey to understand one’s identity, to grow, to heal — the Homeric epic of the self belongs to his men alone. Helen — a panther, St. Lucia, Helen of Troy, Circe — belongs to the text in the same way models are sometimes employed to decorate a room, to be contemplated as an aesthetic object. She is depthless, a fetish. She may be given characteristics— she has a temper, she is a thief, she is a businesswoman — but any attempt at introspection fails. She is always seen from the male gaze, which is why her face is always described as a “mask.” She is mysterious not because men fail to understand her, but because Walcott couldn’t see her beyond her body, beyond symbol.

These Helens are different creatures, / one marble, one ebony […] but each draws an elbow slowly over her face/ and offers the gift of her sculptured nakedness,/ parting her mouth.

I fumbled around, attempted to contextualize the poem in front of me, make it less uncomfortable, more academic, rational. Misogyny may be a recurring pattern in his work, I argued to myself, but that didn’t mean the man was a predator, or even consciously aware of his prejudice. I didn’t know to what extent the man’s writing was a reflection of his person — if anything, in fact, could be deduced from such a comparison.

But there was something there — in my gut, since his work was now intestinal. There was a layer thrumming beneath and through the art, a layer of enormous, toxic, masculine power. One that declares: this is my island, these are my women.

I recalled a particular section of a piece written by Hilton Als, who had visited Walcott in St Lucia.

“Hello, Mr. Walcott,” the waitress said, approaching. She was young and pretty and thin, and was dressed in a skimpy piece of madras cloth. She reminded me of Walcott’s Helen. Walcott turned away from her, mock dismissive.

“I’m not speaking to you, you know,” he said.

“Oh! Mr. Walcott! Why?” She seemed legitimately concerned.

“Dodo!” Sigrid said, chuckling, toying with her camera.

“You’re rude to me, you know,” Walcott said to the young girl, who did not laugh. “You deserve lash! You want lash!”

Walcott pulled the girl over his knee and began to spank her. The girl squealed. Now she was laughing. Her fear had turned to relief.

Walcott let the girl up. “Now you’re rude no more, huh?”

In February this year Als would say, in passing, that Walcott “was a terrible person; awful man.”

Walcott’s toxic misogyny is his great failure as a person, as an artist, in his art, for all three are resolutely bound. His work is lacking. It is flawed. This is a moral and artistic analysis. Both are possible.

That day I Googled “Derek Walcott Sexual Harassment Assault Misconduct.”

Walcott’s toxic misogyny is his great failure as a person, as an artist, in his art, for all three are resolutely bound.

I hadn’t heard of the “Oxford Controversy” before starting my dissertation. There is no mention of Walcott’s behavior in any study of his work, though I think I remember one female critic mentioning how “his” women are almost always caricatures of sex, desire and beauty. It was and probably still is a strict part of English literary criticism, this stark separation of the artist from his art.

Writing this piece feels scandalous, improper, shameful, even: I am fighting four intense years of prestigious English academia, where I was instructed that it would be tasteless to analyze art through the artist’s life. Such a practice would be a return to an obsolete, pre-New-Critical epoch. As a student I was the fiercest proponent of this instruction: reading art through biography requires a certain art, and not everyone is John Berger. Many such readings fail, in spectacular fashion: I had read too many poor essays that analyzed Sylvia Plath and David Foster Wallace solely in terms of their mental health.

If I were to draw anything from the artist’s life it had to be in their own terms: their interviews, their own analysis of how the loss of a lover spawned such-and-such a poem. I was taught to take the artist at their word or not at all. Crossing that line, I assume, would have led to raised eyebrows: “Are you Lacan?” Psychoanalytic criticism, in fact, was taught as part of the Critical Theory module: if you chose to analyze a novel using psychoanalysis, you’d have to make that very clear from the start, and then you’d only use the material in the text to craft your essay. In the end, you’d only be analyzing characters, symbols. Perhaps, as a conclusion, you would allude to the author’s possible understanding of psychoanalysis that would have perhaps informed their work. You wouldn’t connect the dots, as obvious as they were, to the author’s personal life.

Dismissing the biographical seems a little absurd to me, now.

Can you separate the artist from his art? Art, when it is recognized, when it is bequeathed awards and shortlistings — and this recognition alone more often than not involves racial and sexual prejudice — elevates the artist, deifies them even, in this celebrity culture. The artist obtains privileged positions, events, deals, money, tenure. They exert even greater influence and power, as long as they continue to produce, as long as their talent remains intact or grows. This status enables the artist to continue producing art. The work and the person are indissoluble in this respect. The trampling and abuse of others along the way to artistic stardom (or once such stardom is obtained) is also indissoluble from the work of art.

The trampling and abuse of others along the way to artistic stardom (or once such stardom is obtained) is indissoluble from the work of art.

The artist and his art. The academic and his papers. The producer and his films. The writer and his fiction, poems, non-fiction.

When Walcott died on March 17, 2017, the obituaries sometimes contained a little paragraph mentioning his “Oxford scandal.” The “scandal” is a lesson in silencing.

Walcott withdrew from the race to be elected Professor of Poetry at Oxford in 2009; he had done so on account of a so-called “anonymous letter-writing campaign.” The “campaign” was in fact a dossier, received by approximately 200 academics from a group of concerned students, which sought to bring forward the cases of sexual misconduct he had reaped over the years. Excerpts of The Lecherous Professor: Sexual Harassment on Campus by Billie Wright Dziech and Linda Weiner (a book published in 1984) were included in the dossier; these detailed the experience of a Harvard student with Walcott, where she recounted that Walcott sexually harassed her. When she declined his advances, he gave her a C grade and ignored her in class. Walcott accepted the facts of the case, but claimed that his teaching style was “deliberately personal and intense.” He also, of course, slut-shamed her: he apparently had “sensed no reluctance [in the student] to pursue the topic of sexual relationships,” since she had confided in him on a few personal matters. This opinion was shared by Harvard’s dean of faculty, Henry Rosovsky. This case did nothing to stymie Walcott’s winning the Nobel Prize in 1992. The dossier also contained the allegation made in 1996 by Nicole Niemi, who was a student at Boston University and a member of his creative writing class. Niemi stated that the poet threatened to stop the production of her play unless she slept with him.

Walcott stifled these emerging artists’ art, blackmailing their art for their bodies, their artist bodies. Meanwhile, he expects to be judged in terms of his art alone. Few are the ones to say that it is lacking. He may have elevated an island — many islands — and he may have given us islanders a voice, but he did it with a hand pressed to women’s mouths.

He may have given us islanders a voice, but he did it with a hand pressed to women’s mouths.

Walcott described the “campaign” as a “low and degrading attempt at character assassination.” Many respected professors — female professors, such as Elleke Boehmer — expressed their dismay at the decision. “How many male professors of poetry of a certain age and generation can safely hold their hands up and say that they are entirely clear of any history of sexual harassment?” Boehmer told a journalist, whose article ran the headline “Smear campaign dogs Derek Walcott’s bid for Oxford professor of poetry.” That he would have had place to roam and continue his predatory behavior was not, it seems, cause for concern: he would “only” be giving grand public lectures, not teaching a course, and hence, it was to be concluded, students (and faculty members) would be generally safe from harm.

Teach the art as separate from the artist, demands the culture, but revere the artist for his art. Say his art has nothing to do with the man, yet invite him in.

Ruth Padel, who was chosen for the post, resigned after nine days. She was the one who had apparently alerted journalists to Walcott’s misconduct and the letter campaign he was “victim” to during the election process. She was criticized for using his misconduct as a means to get her way. Again, Walcott’s sexual harassment wasn’t the focus of many of the think pieces that emerged that year — that honor belonged to Padel’s seemingly ruthless ambition. The journalist behind one of the pieces even felt bad that Walcott withdrew his candidature: “I wasn’t saying Walcott was a bad poet, just that he was a tiny bit creepy,” he said.

When I told a few other members of staff about what happened with the men who harassed me, I was repeatedly told that I had no grounds for complaint, since I hadn’t actually been touched or “clearly violated” in any way.

“I’m also aware that Byron’s life was not stainless, or T.S. Eliot’s for that matter — would we turn them down? There are other aspects to the character than the sexual. These kinds of concerns are raised when you prioritize character over poetry, and if it came down to absolutely blameless characters, then surely no one could stand. This is political correctness on overdrive about something which happened so long ago.” This is Boehmer again, in another article. Hermione Lee, another professor at Oxford who supported Walcott’s nomination, said that Walcott’s “unorthodox life” should have nothing to do with his job. “Should great poets who behave badly be locked away from social interaction? We are acting as purveyors of poetry, not of chastity.”

Professor Boehmer and Dame Lee. There was a time when I would have given almost anything to be taught by them.

Teach the art as separate from the artist, demands the culture, but revere the artist for his art.

Boehmer and Lee’s arguments are ridiculously flawed. Reading Walcott safely away from Walcott is one thing; having a man openly accused of sexual assault around campus is another. It is shocking that sexual assault is willingly conflated with other aspects of “blame” — that a man’s abuse of power, his harassment, his assaults are somehow the same as, say, one man’s moral failure to support his best friend in a crisis. Repeatedly, I see this same kind of resigned historical fatalism, that what these men have done they will continue to do in perpetuum. To evoke history as an argument is a perfect example of bad faith, of being so wilfully blind that one cannot accept progress. Progress will come, in the form of legislation, accountability. It’s already started.

Walcott’s “Oxford controversy” occurred a decade or so ago. Stars of academia lauded across the world, accused of rape, harassment, abuse, are still safe in their magisterial tenure: Harold Bloom, Franco Moretti. I wonder about some of the writers employed in universities, in creative writing programs. I wonder what they’ve done, what they’re doing.

There is no glory in taking care of your university, its students, and other members of faculty by dismissing a predator-professor. There should be. There is the belief that once a member of staff “behaves badly” and is made to leave, the institution will suffer as a result — whether the institution is a university, a magazine or review, a newspaper. The irremediable loss of a prestigious name, perhaps an institution in themselves. Underlying and concomitant to this is the belief that once a so-called genius is castigated, his genius will somehow be inhibited, and that this in turn would be terribly detrimental to arts and letters around the world.

There is no glory in taking care of your university, its students, and other members of faculty by dismissing a predator-professor. There should be.

Support predators, for they are the bastions of culture.

My own experience let me to believe that nothing that I could say mattered, that the men in question couldn’t be touched, and that if I were to aspire to academia, one day, then I would have to have the department on my side the day I applied for a job, which I clearly wouldn’t get if I had angered them in my refusal to be quiet. I’d like to point out that there were supportive voices, immensely helpful professors who I talked to about this: they looked at anonymous complaint procedures for me, thought about ways I could take action, but I was so terrified back then that I did nothing.

What should I make of Walcott’s work, now? I no longer author-worship. I no longer view his poems and essays as quasi-sacred tracts.

In order to write this piece I had to delve back into Omeros, Another Life, his Collected Poems, his essays, some of his plays. If I read him again, after this essay is done, I’ll probably read him as a poet in his time, though I won’t let time excuse him; read what he did with language, with voice, without forgetting all those he silenced, find out if these voices published any creative work, read them, read them alongside him, read them alone. Read him alongside other poets and writers of the Caribbean: he was so predominant in my life partly because he was one of the only Caribbean writers taught in the three or four lectures on postcolonialism at university. Yet the region is abundant with talent: Edwige Danticat, Kamau Brathwaite, Jamaica Kincaid, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Gabrielle Bellot. Maybe just read them alone.

Read him alongside other poets and writers of the Caribbean. Maybe just read them alone.

When I’m able to read Walcott at such a remove, then maybe then I’ll take what I find to be true and useful in his words and in his technique and separate the artist from his art at last, even though that act may seem deeply disingenuous. But not yet.

Perhaps, of course, I won’t touch his books again at all. This may be the last time I ever read Omeros: there it sits as I type, lilac cover with Walcott’s name in lurid yellow, the title in red. Some designer’s nod to the Caribbean sunset, perhaps. I am about to shelve it. This time, for this last reading of mine, my lips were no longer slightly open in wonder, I took no pleasure in his verse. There is no marvel left; disgust has seared every page, disgust like one of Francis Bacon’s grotesque men, screaming.

I write my island into literature, away and separate from him.