Books & Culture

“Teen Mom” Reality Entertainment Has Been Around for 600 Years

Why do we have such an enduring fascination with the lives of the young and pregnant?

When seventeen-year-old cheerleading captain Lexi performs at the first football game of her senior year on the opening episode of Teen Mom: Young and Pregnant’s first season, her third-trimester baby bump is unmistakable under her red uniform. “I already feel judged,” she says. “They all keep looking at me and talking.” Her baby’s father, sorely in need of a haircut, is in the stands, preoccupied with his phone. “My body hurts so bad,” she groans when the game is over.

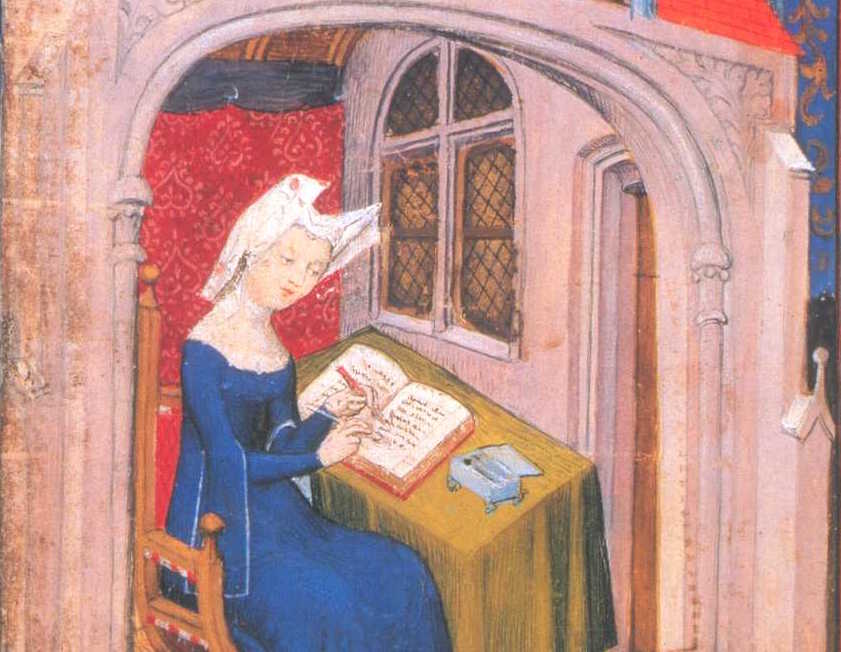

Teen Mom: Young and Pregnant, whose second season just finished up on MTV, is one of a host of similar reality shows—including MTV’s 16 and Pregnant, Teen Mom OG, Teen Mom 2, the short-lived Teen Mom 3, the new Teen Mom: Young Moms Club, and TLC’s Unexpected—claiming to provide an unfiltered look at teenage pregnancy and early parenthood framed through the young women’s perspectives. One could dismiss these shows as trashy reality television voyeurism. But they share surprising parallels to popular medieval songs voiced by pregnant, unwed young women lamenting their unplanned pregnancies, showing that audiences have long been interested in narratives like these. Numerous medieval English songs feature a common scenario: a sexually inexperienced teenage girl meets a charming young man at a party. They dance and drink together before having sex—just like seventeen-year-old Brianna on Teen Mom: Young and Pregnant, who says “Where I got pregnant, how I got pregnant, was totally because of the partying and everything.” He then disappears, leaving her unexpectedly pregnant and alone. She attempts to hide her pregnancy, worries how her parents and employers will respond, and curses the man who impregnated her. Like Lexi reacting painfully to the crowd’s judgment at the football game, one medieval speaker sighs, “My friends now mock me for my misstep.”

Both the medieval songs and the television shows emphasize unplanned pregnancy’s physical, social, and economic consequences.

Groups of young women sang these popular songs at village festivals or dances, giving them a mass appeal directed at their peers—not unlike reality television. The similarities don’t end there: Both the medieval songs and the television shows emphasize unplanned pregnancy’s physical, social, and economic consequences, and they depict young women encountering these consequences alone, with minimal help from their partners. One medieval speaker declares, “I curse the one who impregnated me, unless he provides the child with milk and food,” showing that she is well aware of the financial hardships she will face as a single mother, just as Teen Mom: Young and Pregnant shows Kayla applying for state assistance and trying unsuccessfully to make her baby’s unemployed father pay child support. Lamenting pregnancy’s toll on their bodies, the young woman in one medieval song observes how “my belt arose, my womb grew outward,” echoing Jade’s complaints over her size as she attempts to squeeze herself into an unaccommodating restaurant chair near her pregnancy’s end. “Welcome to the big bitch club!” her mom replies, cackling uproariously.

The medieval songs and Teen Mom shows do share one key difference regarding reproductive choice. Some of the medieval lyrics feature women who contemplate abortion or infanticide: “Shall I keep it or slay it?” one wonders in one particularly popular song that survives in multiple manuscripts. In another, she seeks herbal remedies “to be flat again” from the women in her community, listing a series of plants that were known abortifacients in the Middle Ages. In this respect, the medieval songs are surprisingly more pro-choice than their contemporary counterparts, which portray young women as unhappily resigned to parenthood when they learn that they’re pregnant, or else pressured by family and friends not to have an abortion: Kayla, facing a second unplanned pregnancy, says glumly to her one-year-old son, “I guess Mommy’s gonna have another baby, Zay,” while holding a positive CVS-brand pregnancy test with her long yellow fingernails. When seventeen-year-old Rachel finds out that she’s pregnant again when her daughter Hazelee is only five months old, her boyfriend of one month says, “I don’t want you to fucking kill it, obviously.” Her mom sobs on the couch while clutching a cigarette lighter when she sees the positive test, but then tells her, “There’s not options. You wouldn’t want to get rid of another little Hazelee. You’d regret it for the rest of your life.”

One of the things that has always struck me about both these shows and the medieval songs is their normalization of young men’s abusive behavior. In all the medieval songs, the women’s partners abandon them immediately after sex, leaving them to face the consequences alone. Some are even darker: in one, a girl relates how her boyfriend assaulted her while she was drunk after their date at the village ale festival. “You’re hurting me!” she tells him as he penetrates her, but he refuses to listen. In another, a priest rapes a girl next to a well and makes her promise that she won’t tell a soul. All five young men on Teen Mom: Young and Pregnant’s first season are habitually awful to their partners: Kyler, an inveterate lover of basketball shorts and puffy vests whose hair hangs down in greasy clumps like strands of over-boiled linguine, constantly insults and demeans Lexi. “I love you. Just kidding,” he says as he hugs her goodbye at her graduation party, smirking as her face falls. Stephan, the father of Kayla’s son Izaiah, steals her debit card and drags her from a car, hitting and kicking her until her friend calls the police. The next day, Kayla’s mother kneels on the ground, using her phone to photograph the plum-colored bruises on the backs of her daughter’s thighs. Ashley calls the police on her boyfriend Bar after he comes home drunk and attacks her. “I know that he shouldn’t put his hands on me. I know,” she says later, wiping tears from her false eyelashes. While driving past an Indiana Dairy Queen, Sean admits to verbally abusing his partner Jade in front of their baby and confesses to his sister, “Sometimes I say meaner things than I should.”

These narratives discourage rosy ignorance about the realities of teenage parenthood.

Why are these teenage pregnancy narratives so wildly popular in spite of the six centuries that separate them? Why, in spite of the advent of reliable birth control and condoms as well as the lessening of cultural taboos around unwed pregnancy, are we still fascinated by narratives of young women who are unmarried, unexpectedly pregnant, and struggling? Why do we watch them, and why did medieval people sing them at festivals and copy them in manuscripts? On one hand, these songs and shows could serve as educational warnings to other young women: don’t have unprotected sex, the implicit message goes, or this could be you. “For more information on preventing pregnancy and protecting yourself, go to itsyoursexlife.com,” a confident female voice declares during commercial breaks on all Teen Mom programming, implying that the show’s viewers are young women who do not want to get pregnant. These narratives discourage rosy ignorance about the realities of teenage parenthood by portraying the accompanying struggles in vivid detail: Brianna needing childcare in order to keep her job but wondering how she can pay a babysitter when she makes only $12 an hour; medieval servant girls terrified of losing their jobs once their employers discover their pregnancies; Kayla dropping all her college classes because she doesn’t have childcare, much to her advisor’s horror. The fact that these “lessons” about avoiding unplanned pregnancy are still necessary also point, more starkly, to the fact that things between the Middle Ages and now have not changed as much as we might think: birth control is not as widely available or accessible as it should be, young men’s abandonment and mistreatment is still portrayed as inevitable, and affordable childcare and other forms of economic support remain sorely lacking.

On the other hand, the shows are voyeuristic, featuring repeated scenes of teenagers in labor sobbing and screaming in hospital beds, their hair spectacularly disheveled. We see Ashley hobbling around painfully in a nightgown after giving birth. Jade declares, “My vagina feels like it is on fucking fire with, like, gasoline,” on the car ride home from the hospital. The men who copied these medieval songs into manuscripts were often clergymen, a detail that is particularly alarming because most of these songs feature clergymen exploiting, coercing, and abandoning young women. In this context, the songs could represent clergymen making fun of young women’s naïveté, sharing tips for how to take advantage of them, and mocking their distress. There’s a fair amount of potential schadenfreude in watching these shows or singing these songs: they depict teenage girls suffering after having unprotected sex with poorly-chosen partners, enabling us to feel better about our own lives and choices while seeing these young women “get what they deserve” for breaking the rules.

Sixteen and Pregnant first aired on MTV in 2009, when I was midway through my six-year Ph.D. program. I spent way too much time watching episodes on my laptop late at night when I was supposed to be writing about medieval pregnancy laments for my dissertation. It seemed as though everyone my age was getting married, buying houses, going on vacations, and starting families while I was stuck as an eternal student in a tiny studio apartment. I found these shows to be oddly comforting, since they made me feel as though I had my shit together by comparison, and they reminded me that my issues were relatively minor. Sure, I might have to ditch the chapter I’d been writing for four months and start over from scratch because it turned out to be a dead end, but at least I wasn’t leaving my baby with my mom to do heroin with my new boyfriend, or sobbing in a Michigan parking lot after giving up my baby for adoption.

But I also knew that I could have been—and that idea may be the true heart of our centuries-long fascination with teen mom stories. As my sister pointed out in a late-night conversation about our mutual devotion to Teen Mom programming, these narratives encourage audiences to identify and empathize with the young women duped and abandoned by unsavory men. This is especially clear in the medieval songs, which feature young women doing activities that would have been shared by wide swaths of the population—completing everyday domestic tasks, dancing with their friends at holiday celebrations, drinking at church-sponsored ale festivals, accepting courtship gifts from attentive young men—in order to remind audiences that they, too, could just as easily be in their position. These narratives encourage us to think back to the losers we dated in high school, all the shaggy-haired assholes we were attracted to, all the poor judgment we showed, all the foolish risks we took. Kayla, facing the prospect of parenting two children under two years old and realizing that she won’t be able to return to school any time soon, says, “I feel like I’m, like, failing. Like I had a plan for my life and it just did not go that way at all.” These shows—and, even more explicitly, the medieval songs—serve as uncomfortable reminders that many of us, no matter how firmly we believed in our naïve bravado that we knew what we were doing and that our lives would go according to our plans, could have ended up as the center of one of these narratives.