interviews

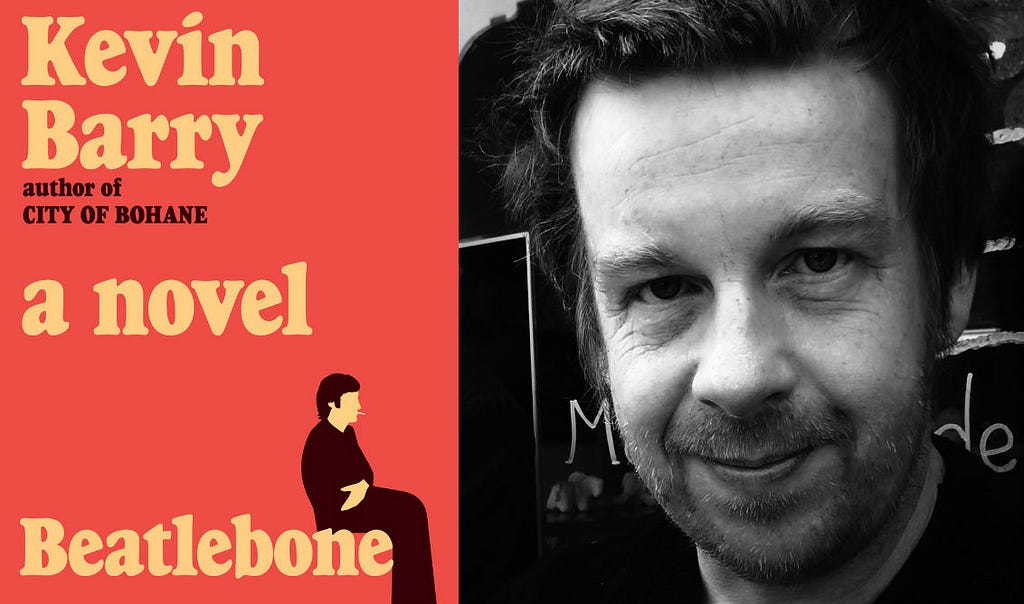

Madness At The Edges: A Conversation With Kevin Barry, Author of Beatlebone

by Dan Sheehan

Kevin Barry is an Irish novelist and short story writer whose linguistically dextrous, darkly comic, and sometimes phantasmagorical style has produced some of the most critically lauded and cultishly followed fiction of recent years. The impact of his Rooney Prize-winning collection of short stories, There Are Little Kingdoms, has been credited by many as the first major catalyst for the recent post-Celtic Tiger fiction boom in Ireland. The success of his debut novel — the futuristic west of Ireland gang saga City of Bohane, which received the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award in 2011 — was instrumental in introducing Barry to a wider American readership. The New York Times called it “an extraordinary first novel…full of marvels…as true as the Macondo of Gabriel Garcia Marquez [or] the Yoknapatawpha County of William Faulkner.” In 2012, “Beer Trip to Llandudno,” a story from his latest collection, Dark Lies the Island, won the Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award, the largest monetary prize in the world for a single short story.

Barry’s new novel, Beatlebone (Doubleday 2015), tracks an imagined excursion taken by John Lennon in 1978 to Dorinish, his uber-remote private island off the Mayo coast. With the help of a philosophical local fixer named Cornelius, John evades the British tabloid press; falls down a psychological rabbit hole with a sinister communal trio of Primal Screamers inside an abandoned hotel; and considers his relationship with his wife and parents, his music and memory. All of this while trying desperately to make it to a gnarled, inhospitable piece of rock in the stormy Atlantic, where he can finally be alone with his thoughts.

Barry spoke to me over the phone from his house — a former police barracks in rural Sligo, on the west of Ireland coast. Warm, candid, and prone to excited bursts of expletive-heavy remembrance, he talked about Lennon’s real life interactions with the Irish communes and crazies of the 1970’s; his fascination with the idea that “human feeling settles into places”; the importance of a varied writing life; and his impending return to the anarchic world of Bohane.

— Kevin Barry will be in Brooklyn launching Beatlebone at Greenlight Bookstore, co-hosted by Electric Literature, on Tuesday, November 17th, at 7:30 pm. RSVP here. You can find his story, “Wifey Redux,” in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading.

Dan Sheehan: Beatlebone is somewhat of a departure from what you’ve done in the past. Why did you choose a real historical figure as the focus for this novel? Why someone as iconic as John Lennon?

…it’s a tall tale, and that’s the area I’m always interested in bringing the reader out toward. That edge of believability, where the reader is thinking to themselves “ah c’mon, no fucking way…but maybe.”

Kevin Barry: Without wanting to sound too Flann O’Brien about it, my bicycle brought me to this one. I go out cycling around Mayo and Galway in the summer and since we moved to Sligo I’ve been doing that every day or two. I’d be looking down at Clew Bay and all the tiny islands, and I had this weird little piece of information in the back of my brain: that John Lennon used to own one of those islands. So I starting Googling this — research would be too fancy a term for it — but I didn’t really know what I was up to. I thought that maybe I could make a little radio documentary about all this or maybe I could write an essay about it. But then I found myself scratching down lines of dialogue and I thought “uh oh, I’m in trouble here” because I was obviously going to start doing this as a piece of fiction. It’s a very risky thing to take such an extraordinarily iconic and important figure and just land him into one of your stories, unasked (laughs). This one took an enormous amount of work in terms of drafts, and the sheer amount of words written out in my shed, just to get the voice to a place I was happy with. I went through lots of variations of voice for him in the book; I tried first person, second person, third person, past tense, present tense, future tense and eventually I just decided to fuck it all in there. I guess what I wanted to do, to use the Joycean term, was to give a portrait of the artist. I wanted the reader to be lowered down into a kind of cauldron of a creative brain and see what that would be like. It was on my desk for about four years. The last year of that was great fun, when I had the voice for the book that I was happy with, but to get to that point took a lot of heavy lifting. Endless drafts and cutting and cutting and cutting until it sounded like it could almost be him. I guess where it’s similar to my stories and my previous novel, City of Bohane, is that it’s a tall tale, and that’s the area I’m always interested in bringing the reader out toward. That edge of believability, where the reader is thinking to themselves “ah c’mon, no fucking way…but maybe.” Very often, with the stories, I find that on the surface they’ll be presented as a kind of realism but then very quickly that starts to fade away at the edges and you realize that you’re in a different kind of world altogether.

DS: That was one of the aspects of the book that I found most interesting: that this is recognisably John Lennon, but he’s also very much embedded in your world, he’s playing around in your wheelhouse. How did research play into to this approach? I mean, there must be hundreds of books written about Lennon and the Beatles but they probably didn’t do you much good.

KB: I was actually very keen not to do any traditional research because, as you say, there’s just so much stuff out there on Lennon and The Beatles that if you open that cupboard door the whole world falls out on top of you. The only real research I did, and I mention this in the essay in the middle of the book, was watching YouTube clips, a lot, and trying to get the rhythm of his spoken voice right. That was really difficult because he’s very changeable in tone; even in the course of a single sentence he’ll go from fluffy to very spiky and thorny and it’s hard to get that down on the page. I developed this weird psychological tic while I was working on it as well where if I saw something on the TV about him, or something in a magazine, I would have to look away. I didn’t want the real world to intrude too much on the fiction. I wanted to have it as a very separate, alternative universe, a might-have-been story. It was interesting for me later on, toward the end of the book, when I did look at a couple of things here and there. I found a book written by a photographer who had been quite close to him who said that late in life Lennon had started to make these odd little solo trips. He went to Japan and he went to South Africa, and it was really nice to find out that my nutty little story was something that really could have happened. And of course underpinning all of it was the connection to county Mayo and how he had been talking about renewing the planning permission with Mayo County Council. There’s just something delicious about the idea of John Lennon and Mayo County Council having dealings with each other, you know (laughs)? I just couldn’t leave that alone.

DS: When worlds collide.

KB: And I think the book started sitting up and coming to life on the desk when I gave him his sidekick, Cornelius. That was a very important thing for the story. It made me discover that John was on this quest and he had this sidekick and so this was the most old-fashioned book on the planet really. It’s essentially Don Quixote. It’s tilting at windmills. There’s nothing new under the sun in the novel, as we know. It’s just what you can do within that, what you can do with the sentences. What I’m interested in is trying to get as much intensity as I possibly can into the sentences, whatever form that may take, whether it’s a comic intensity or whether it’s about getting other emotions down onto the page. I’m rambling spectacularly here, Dan, as always.

DS: Ramble away, Kevin. This is good stuff. But now that you mention it, did that approach, that focus on the intensity of the sentence, factor into your decision to mix writing styles in this novel? I remember hearing a podcast interview you did recently where you said that you love to read your work aloud and collaborate with people in other literary disciplines, describing how one form can aid in enhancing the power of another. In Beatlebone you have stream-of-consciousness sections, you have an essay, you have an intense passage in the Amethyst Hotel that’s almost like a play. How did you decide on what mode to use and where?

We still love to hear stories told to us. We’re all fundamentally children at heart in that regard…

KB: I kind of threw the fucking kitchen sink at it to be honest! (laughs) What the book seems to be like, more than anything, is kind of like a radio play of a novel. It’s a story for voices that primarily works on these kinds of dialogues and monologues. It goes back, I suppose, to the way we take in our stories now and the way that we process narratives and fiction. We’ve all clearly become much more impatient as readers because we’re online all the time and we’re much more inclined to flit around from one thing to another. But I do think that one thing which can still stop us and arrest us, that can slow us down, is the human voice. When we hear voices aloud. This explains why podcasts have become so popular, it explains why there are so many literary festivals now. We still love to hear stories told to us. We’re all fundamentally children at heart in that regard, and I think I’m trying to get that down on the page. This book is supposed to have an oral feeling to it. One of the literary references that’s constantly made in the novel is to Dylan Thomas, who John was apparently obsessed with as a teenager, as all teenagers should be. I found in places that the world of the book was moving toward a kind of Under Milk Wood world. It seemed suitable because there was that link, he had loved Thomas’ work. The main thing for me, always, is to give myself a good time at the desk. It’s based on the very straightforward assumption that if I’m having a good time, the beloved reader at the end of the process will be having a good time too. And what I love about the novel as a form is that it is so capacious; you can kind of do anything as long as the reader is having a good time. You can throw in a play and you can throw in an essay and you can put in a crazy five-page stream-of-consciousness monologue, or whatever, and if the reader is having a good time line-by-line-by-line, they’re happy to go with you to the ends of the earth. Which is great because even though there’s nothing new about the novel and even though it has all been done before, it’s infinitely adaptable. You can try anything inside it, which is why it’ll never go away.

DS: I love that idea of the big, meaty, anarchic novel where you can find space to fit in little nuggets and gems of writing that would otherwise have to be reluctantly discarded. Do you squirrel away bits of abandoned projects to reuse when you find a suitable opening?

But I love for nutty things to happen in books, for mad things to happen around the edges, because it’s not a rational or sane way to proceed with your days or to proceed with your adult life, so why not have a bit of fun with it, you know?

KB: For sure. It’s a sort of authorial thrift. Actually, I got the opening lines for this novel very late on, literally in the last couple of weeks. It’s interesting, sometimes you have a novel on the desk for four years and then it’s only in the last few months and weeks that you can suddenly make big improvements very quickly, because you finally have the tune of it, the melody of it, right. For example, on the last morning before I sent the novel off to its various editors, I wrote in a whole new character: a one hundred and twelve year old woman named Margaret who shows up toward the end, just for a page or two, and kind of talks to John about life. I did call my wife out to the shed that morning to tell her that I’d just put a new character into the book and she went “ah fuck, you’re sending it off at three o’clock!” (laughs). So I showed her the pages and asked if she seemed ok and my wife said “yeah, she’s good. Leave her in.” So I did, and nobody has complained so far. Everyone seems to be very fond of the one hundred and twelve year old woman who shows up at the end of the book. But I love for nutty things to happen in books, for mad things to happen around the edges, because it’s not a rational or sane way to proceed with your days or to proceed with your adult life, so why not have a bit of fun with it, you know?

DS: Absolutely. The hundred and twelve year old woman chastises John for swearing, if I’m remembering correctly?

KB: She does yeah, and she says “the other boy was lovely, the other young fella in the band.” Something like that. She’s a Paul fan obviously.

DS: John would have loved hearing that in the mid-to-late 70s I’m sure.

KB: He would have I’d say.

DS: But even though the book’s incidents are outlandish, they’re also grounded in an historical reality, aren’t they? There were primal screamers and hippie colonies living out in the west of Ireland during that period.

KB: It’s funny, Dan, when you read back through Irish literature of that era — of the 60’s and 70’s and 80’s — it’s all small town stuff, stuff about the farm. And that’s brilliant, fine, but there’s no reference to the fact that the west of Ireland was full of freaks as well at that time (laughs). When I was growing up in Limerick and being around the west of Ireland on holidays, there were always fucking gangs of hippies and primal screamers wandering about. I remember there being a commune of streakers around the corner from our house in Limerick. Crazy stuff going on. It was the end of the hippie trail. It was cheap to come and settle in the west of Ireland so it became full of nuts, who really improved the place. Anything good that happened in the west of Ireland in the last fifty years has been because the freaks moved in and changed the nature of the society there. It used to be this catholic monolith, and it’s fucking not now, because all the crazies started to arrive. It was fantastic and it saved the place. But it struck me that this whole thing had never really shown up in Irish literature, not to any significant degree. You’d see some bits of film here and there — like a Bob Quinn picture or a documentary — but that was about it. So I thought it was very sweet to come across the fact that John Lennon actually had a very real, concrete role in that period of history. When he gave his island to the Diggers, that was really the first organized commune in the west of Ireland as far as we know. So it was really nice that this person, who apparently considered himself to be very Irish, played a role in freaking-up the west of the country!

DS: A much-needed freaking-up.

KB: A much-needed freaking-up of the western zones, yeah.

DS: It is strange to me that writers, for so long, refused to embrace this idea of the west of Ireland as a weird, mythic, psychologically potent place — something which appears time and again in your fiction, whether it’s the Ox Bow Mountains, or Clew Bay, or Bohane.

KB: Well I think that if you go back far enough it’s there. I reviewed a book over the summer called cré na cille, or The Dirty Dust. It’s a Máirtín Ó Cadhain book, an Irish language classic from the 1940’s, just translated into English, and it’s fucking crazy stuff. So if you go back through Irish language literature and through Flann O’Brien and Laurence Sterne and all of that, there was some fucking mad stuff being written. I think the country tried to appear to be in some ways more sophisticated than it was in its literature for a while, as a sort of post-colonial hangover, and we lost any sense of connection with the fact that the place is tuned in to some very weird frequencies. It is nice to think that there is another world out there when you’re writing about the west of Ireland. I’ll get some really strange buzzes off parts of it when I cycle around on my bike. You mentioned the Ox Mountains; fucking hell, man, that place. Whenever I’ve cycled over there I’ve always gotten this deeply weird malevolent fucking vibration of the place, and I knew I was going set a story out there eventually. I think, for me, that’s where stories come from initially. They almost always come from a geographic inspiration. It’s always a place. I pick up on some weird energy and start to write something for that. I used to think that my stories came in with dialogue and started with the ear, but I think the truth is that it’s places more than anything. And I’ve found that to be a very good reason to get out of the house, not to just sit in my cosy little writing shed all the time. Because if I do that I’ll inevitably start writing the novel about a guy sitting in his shed. You have to get out, and you have to listen to people, and you have to tune in to weird energies so see what comes up.

DS: Is there anywhere you’ve been outside of the west of Ireland that can compare to it in terms of that weird, psychic energy?

KB: Well I travel quite a bit and I’ve lived abroad quite a bit. There was guy down in Kerry — a philosopher who died in 2007 named John Moriarty. I saw a very interesting interview with him recently where he talked about how, depending on where you are and what kind of landscape you’re in, your brain feels a different size. He described spending time in Canada, and how his brain felt like a little pea when he was out in that vast landscape. But then when he was back in Kerry it felt like a huge melon! The odd thing is that one of the most important decisions you can make in your writing life has nothing directly to do with the writing. It’s the decision of where to put yourself, where to locate yourself, because that’s going to start feeding into the work, inevitably and very strongly. I mean, I didn’t move to rural county Sligo for literary reasons. We moved here because it was one of the last affordable places to buy a house during the Celtic Tiger, but it ended up working out very well for me because it’s brought me back to the west of Ireland again, and to a part of it that I didn’t know all that well, so it’s fresh to me. I didn’t know Mayo, I didn’t know Sligo, I didn’t know Donegal. So it’s definitely opened up new and strange worlds to me. Wild, elemental places.

I’ve always had this belief that human feeling settles into places — into the hills and into the stones and into the streets and into the buildings — and it lingers there.

You realize how sparse the country is, in terms of population. There’s a kind of eeriness to it, a hauntedness. I read an article in the newspaper last weekend about how Ireland at one point had eight and a half million people in it, and now we have about four and a half. It was a busier place in times gone by, and there is a haunted air to it sometimes. I’ve always had this belief that human feeling settles into places — into the hills and into the stones and into the streets and into the buildings — and it lingers there. In Beatlebone John and Cornelius are constantly tuning into these vibrations as they drift around.

DS: You actually drifted around these places yourself, right? The island, and the old hotel, and the remote coastal caves?

KB: Yeah, all of that stuff from the essay in the middle of the book is more or less true. I went out to the island and I did scream and I did have a look around the Amethyst Hotel. Actually, it was something that started with that Ox Mountain short story I wrote. I said that I would try to write a story on location in the actual place where it’s set; and then I adapted that for Beatlebone. So I was going out on these trips with a load of tape recorders and note books and jotting stuff down very directly on the page as I drifted around. Literally cycling around, stopping the bike and writing things down, almost like reportage. What I love about this book as well is that it’s opened up new areas of interest for me. I’m now very interested in essays having only done a few in the past while — and also in writing plays. So the book is prodding me in unexpected directions, which is really cool. It’s a nice to have new possibilities open up for your writing. I have a lot of friends who are visual artists and they’re much less set in their ways than writers; they’re much more inclined to try new things all the time and to investigate their practice, the way they go about things, their methods. And I get inspiration from that. I think you should always be trying to change. I really hate this idea of the writer who finds a voice, and then writes in that voice for forty years.

DS: Until no one wants to hear it anymore.

KB: It just seems like utter tedium to me. I much prefer the idea of letting the story, or letting the project, dictate the voice and the style.

DS: I remember reading recently about novelists like Alex Garland who, having dipped a toe into a more collaborative literary field like Hollywood screenwriting, found it to be so exciting and addictive that they ended up moving away completely from where they originally started. Can you see something similar happening in your own career, or will you always return to prose fiction?

KB: Well I’ve done bits of everything over the years; I’ve had a couple of short films made and I’ve written longer, feature-length scripts and plays. I guess by nature I’m quite sociable. I like getting out of the house and I like having colleagues. When it’s prose fiction it’s just you and the four walls, so increasingly, when I open the laptop I have two folders: one says ‘scripts’ and one says ‘stories.’ I’m in a weird situation lately in that whatever I’m working on, I’m not sure what folder it’s supposed to go into. The stories are turning into monologues and the scripts are turning into stories. But I’m definitely drawn to actors, I’m very sympathetic to their plight, because it’s a real, vocational thing that they do and I increasingly find myself writing for them, in whatever form that might take.

I also think that, pragmatically, in a writing life it’s a good idea to be doing a lot of different things, because you’re certainly not going to make a living as a short story writer. Very few people can even make a living as a novelist these days so having plenty of pokers in the fire is a good thing.

Over the last while I keep making attempts at plays, and they’re fucking hard. With a dramatic piece you can’t just tell a story, you also have to build a little machine with all its component parts that’s going to work in a room forever. It’s slow work. I slide through the dialogue but then what’s around the edges of that takes a lot of thought and a lot of drafts.

DS: I suppose you’re also put in a new position where people are telling you what you can’t do. You’ve spoken about City of Bohane and the planned adaptation; how in the writing of the story you could create this gigantic, labyrinthine world full of battles and costumes, and it didn’t matter because you and the reader were doing the work, but once that moves medium to theatre or TV or film, budgets come into play.

KB: That’s the glorious thing about writing short stories or novels: you can do whatever you want. All that’s holding you back is your own imagination. It is interesting though, how working in one form can benefit you in another, and I think you learn a lot about yourself, as a short story writer say, by writing a play, and visa versa. Only positive stuff can come out of trying new things and finding what’s right for you. Everyone is going to change as they move through a writing career as well. I look at someone like Gore Vidal and I really admire a career like that, because he did fucking everything! He had a long period where he was a screenwriter, he had a long period where he was a Broadway playwright, later in life he became a renowned essayist, he was an historical novelist. He just did the lot, and I love that polymath approach. I guess I have a kind of impatience as well; I’d go nuts if I was only writing short stories or if I was only writing novels.

DS: And why not? If you can combine forms in a book and that book becomes successful, why not use that as a springboard? Who sets the rules for what type of writing you’re supposed to do going forward?

KB: Right. I want to be unpredictable to myself as much as to a reader. I want to surprise myself as a means of keeping myself interested. I want to present stuff that people don’t expect. There’s a great quote from Harold Pinter, who said once “don’t ever give them what they think they want,” which I think is kind of heroic. When I published my first book of stories it went down well; they were quirky, funny stories often with small town settings, and I guess then when I was about to publish a novel I would have been expected to create a similar world, and I didn’t do that. And sometimes people can be a little tetchy when you do something that they’re not expecting, but fundamentally it’s just about trying to keep myself engaged with what’s going on on the desk.

DS: Do you think you had that impulse even before you started writing? I know you worked a number of different jobs when you were younger including being a court reporter in Limerick, where you were able to just observe this array of darkly comic, verbose, grotesques.

KB: Yeah, my first job was as a cub reporter when I was a nineteen year old in 1989. And it was really weird, starting to write a novel nineteen years later and having no idea that those two or three years spent in court houses and council meetings in Limerick would serve as large part of the research that was needed for City of Bohane. I didn’t even realise that when I was writing the book, but when I look back on it now with a little bit of perspective it’s clear that while the book is a fantasia set in an alternate future, it comes from growing up in Limerick and Cork in my twenties and it’s really about how small cities operate. The interconnections and the sense that, even though the rest of the world is out there, really it’s just a kind of rumour. Nothing really matters unless it’s happening on O’Connell Street in Cork or on Patrick Street in Limerick, or on De Valera Street, as it is in Bohane. Where you are is the center of the universe and anywhere beyond city borders is Big Nothin’. But all the research for that, unbeknownst to me, was sitting in court houses in Limerick City, which as you can imagine is a ripe education. Sometimes the best research happens when you don’t even know you’re doing it, when you’re just going through your day-to-day life. But it can take a long, long time for it to filter into the fiction. I regularly look back at my short stories and ask myself “where did that come from?” Often it comes from periods of your life, feelings or emotions, that happened ten, eleven, twelve years ago, and it takes that long to hang around at the back of the mind, in the subconscious, where all fiction begins, before it’s ready to be transmuted. Maybe it needs to embitter you (laughs) for a few years before you can use it in that way. I don’t do any teaching but I sometimes give talks in colleges to young and emerging writers and the one thing I always say is that it’s really hard to write about what happened to you last week or even last year. It can just be too soon. It needs time to compost, to get murky, before it’s ready to come into your work.

DS: I wanted to ask you, Kevin, about whether or not there is a sequel to City of Bohane in the works. You built such a detailed, kinetic world in the novel, it seemed to me that any one of those main characters could have their own spin-off.

I’m going back out to the quare place…Because when you build a city it feels like real estate, and you might as well use the fucking place.

KB: I am definitely going back. I’m going back out to the quare place. I wouldn’t be promising trilogies or anything like that, but I did feel, even when I was in the middle of writing the first one, that I was going to do at least one more. Because when you build a city it feels like real estate, and you might as well use the fucking place. About two years after I wrote it I was recording the audio book, and I noticed that I was having great fun whenever the characters Jinni Ching or Girly Hartnett appeared. The thing I felt was most lacking in the book was that these two main female characters weren’t in it enough, so I can’t wait to go back to Bohane to see what they’re up to. Nothing good I expect. The plan is to head back out there on the Winter Solstice, December 21st, and to return on the Summer Solstice, with the tablets of stone!

DS: Ready to greet the world again.

KB: I definitely don’t intend to spend fucking four years on this one. I wrote the first Bohane novel inside a year, and I have the language for it now, I have the world, so I think I can get the second one down pretty quick. I’m curious myself, in a weird way, to find out what’s going on out there and the only way to do that is to sit with it in the shed for at least six months. I wrote City of Bohane in 09/10 so I’ll be going back to it six or seven years later with more experience as a writer, and probably with more technique in some ways. But what I’ll be really interested in is to see if I can get the same vitality into the sentences, if I can make the sentences pop, because that’s what elevated the first book, that’s what I was happy with. And I have no idea what’s going to happen. Maybe it’s going to be a really quiet Bohane book, a subtle novel with no gang fights or brash fashion descriptions (laughs) or love triangles. It could just be pure kitchen sink realism.