interviews

Ben Lerner Is Apprehensive: John Freeman Profiles The Newly Minted MacArthur Fellow

by John Freeman

Just before news broke that Ben Lerner was among the 2015 winners of a MacArthur “Genius Grant,” John Freeman sat down with the novelist to discuss his body of work, his fears for the future of American discourse, and the newest changes coming to his life.

IN SEPTEMBER OF 2001, Ben Lerner was living in a profoundly unclean house in West Providence with his childhood friend Cyrus Console. The two poets were finishing their graduate studies at Brown University, living like young bohemians. They drank a lot of green wine–the nearby liquor store being run by a Portuguese man–and whiskey at night. Console fed red meat to the bats which circled their back yard in the small hours. “I don’t think we ate a vegetable the whole time we were there,” Lerner remembers. “We did manage to finish our first books in that very, very, very cold house.”

It was also in that cold house, on the morning of September 11th, that Console woke Lerner to watch the news of the attacks on the World Trade Center. They saw a lot of news in the days to come. Among the circulating stories was an item from a major news network about the face of Satan appearing in the smoke of a burning tower. “That moment of the faces wasn’t an end of innocence about American empire,” Lerner says now, “it was a realization that the forces of empire no longer even had to pretend to speak a discourse of reason…that the debasement of the language had reached a new level.”

But when Lerner opens his mouth and begins talking about the phenomenology of an unequal and uncertain future, or the unsustainability of our lifestyle, it becomes clear that these are more than just phrases to him.

Lerner tells me this in an email, but the remarkable thing about this novelist is he speaks this way in person, too, without sounding, well, like he’s on a panel at the Brooklyn Book Festival. Sitting outside of a Park Slope cafe which sells $4 flat whites and gluten free cakes, he looks every bit the Brooklyn cliché: retro trainers and glasses, a large iced-tea in his hand. His smashed-screen iPhone sits by his side, buzzing every few moments. But when Lerner opens his mouth and begins talking about the phenomenology of an unequal and uncertain future, or the unsustainability of our lifestyle, it becomes clear that these are more than just phrases to him. That if we are going to examine the morality of privilege in this present moment, a need to reclaim language and its precision is paramount.

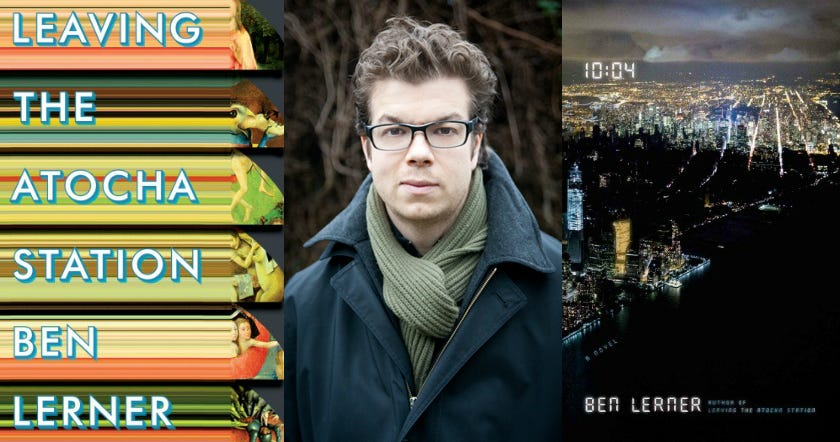

The reason we’re sitting here at all is not Lerner’s poetry, which has won him awards and made him the youngest National Book Award finalist in recent memory, or the recent MacArthur “Genius Grant” he won, but a novel he wrote “by accident”: Leaving Atocha Station. Named after the Spanish rail station that was bombed by terrorists in 2004, the book tells the story of a young poet named Adam who travels to Spain on a Fulbright Grant, as Lerner did. Adam spends his days wandering around museums, smoking hash, chasing two different women. From page to page he flails in a sea of self-doubt and feelings of his own fraudulence.

The book might have long since been relegated to the slag heap of novels about loser writers if it weren’t so funny and acidly observant. Adam’s self-loathing torques constantly around his American insularity. Yoked into the company of various groups of Spaniards, who are busy protesting, Adam tunnels ever deeper into his own neuroses, fantasizing and wishing that another bomb would go off and imagining, if it did, his “friends from the U.S., their amazement and envy at the death I had made for myself, how I’d been contacted by History.”

Ultimately, Leaving Atocha Station is a profound study of two linked questions. The first, as Lerner explains, is whether you can “ground your relationship to art in anxiety about your inauthenticity.” Adam has gone to Spain in order to write an epic poem on the Civil War, yet he writes barely a word. He becomes convinced poetry is useless. This thrashing around the idea of poetry’s supposed power is an issue that Lerner has given a lot of thought to. Not long ago in the London Review of Books, Lerner laid out the ways in which poetry, to be poetry, must fail, for the idea of the poem in the writer’s head is never fully achieved. A book version of the essay will appear next year.

The novel’s bigger question, though, concerns American power and the peculiar morality of privilege and self-identification in this present moment. As Lerner says, “it’s about how you reencounter the American in terms of violence and assimilation and capital, even going abroad. And so you have this weird way of both reinventing yourself but also getting your news about the bombing right next to you from reading the New York Times.”

Outside the Park Slope café, I ask Lerner when these preoccupations originated with him, and his answer is as clear as it is unexpected. It throws a wrench into anyone seeking to relegate the United States to a monolith with a useless fly over region at its center. “I grew up in a lefty Jewish family in a very red state with an outspoken feminist mom and had been a student of political theory and the left tradition,” he says, “so my sense of the politics of language–or the debasement of the language in the context of capital and empire–was there growing up in the 80s and part of what drew me to poetry in the first place.”

In other words, he learned it in Topeka, Kansas.

* * *

A BRIEF DETOUR here is necessary. There are parts of Kansas which are well-known pockets of liberal life, such as Lawrence, where William S. Burroughs lived out his later years in walking distance of the University of Kansas, and with its coffee shops and gay nightlife. Or Wichita, which recently voted to decriminalize marijuana possession down to a $50 fine.

Topeka is not one of them. The city is better known for racial strife. It was home to the first black kindergarten west of the Mississippi and it is where Oliver Brown, a welder in the Santa Fe railroad, participated in a class action suit against the U.S. government to argue that the “separate but equal” segregation of schools was unconstitutional. He won and a whole new chapter in America’s race war began. Topeka is the state capital, but drive a few miles outside of town and there are huge skies.

“It was a fine place to grow up,” Lerner says. “It was just very open…The Kansas poet William Stafford talks about a ‘treasured unimportance’ about Kansas….There was no exclusivity, in good and bad ways. There were no fine arts…but there was also…kind of an openness.”

Lerner’s parents were both family psychologists, and worked at the Menninger Clinic, a psychiatric institute founded in the prairie in 1925. In addition to being a clinical psychologist, Lerner’s mother is a writer and author of the influential The Dance of Anger, which was a New York Times bestseller and the first book in the United States on the subject of female anger.

The Lerners had dinner together most nights and encouraged their sons to talk and be expressive. “It wasn’t group therapy,” Lerner explains, “but [family life] was really, really verbal. It was…about sharing feelings and not withholding stuff.”

Cyrus Console, the Providence housemate who grew up in Topeka a few years ahead of Lerner, remembers his friend’s verbal skills as beyond precocious: “In high school he was something of a ‘tough guy’ but also of course one of the nation’s all-time greatest champions in debate and extemporaneous speaking.” Console isn’t exaggerating. Lerner was the state extemporaneous speaking champion all four years he was in school and national champion his final year of high school. He is the all-time national points leader in forensic debate. This is not just a nerdy version of glory days. It was in these dusty high school gymnasiums in tiny towns–watching competitors ‘spread’ a debate by raising the maximum number of arguments, however silly, forcing their opponents to reply to each and every one– that Lerner glimpsed a frightening vision of American political discourse.

At nights following debates Lerner would attend beery house parties and switch to another primary discourse of the time–hip-hop–and participate in freestyle rap battles. A comical image given that nearly all of them were white and upper middle class. Several years ago Lerner wrote a piece in Harper’s Magazine that spelled out how this unlikely collision of speaking modes formed the person he is today:

“When I was in my Dillard’s suit spewing arguments in a largely empty school, when I was a belligerent little wankster rhyming in a basement, when I was an ignorant undergrad abandoning the clichés of my macho midwestern romanticism for the clichés of poetic vanguardism, I was, in all my preposterousness, responding to a very real crisis: the standardization of landscape and culture, a national separation of value and policy, an impoverished political discourse (“There you go again”) that served to naturalize our particular cultural insanity. I was a privileged young subject — white, male, middle class — of an empire in which every available identity was a lie, but when I felt the language breaking down as I spoke it — as it spoke me — I felt, amid a general sense of doom, that other worlds were possible.”

Two of Lerner’s high school mentors, Ed Skoog and Eric McHenry, were former Topeka debaters and through their guidance Lerner began to look to poetry as a way to at once meaningfully connect and rescue language from its increasing degradation. Then luck intervened. At sixteen, Lerner was browsing in a Topeka Barnes & Noble and picked up a John Ashbery book off a prize-winners section. “I was baffled, dizzied,” he remembers. “I had no sense of liking it or disliking it–I was initially just caught up in the strange machine of it.”

Lerner wasn’t alone in this drift toward poetry. Console was writing his own verse, as were a striking number of other local poets. In fact enough poets emerged from Topeka in that decade that one could label them a school, were it not for their aesthetic differences.

Many of these poets stayed in Topeka. Lerner knew he wouldn’t. “I was always going to leave Topeka for college and did not feel trapped there,” he wrote in the Harper’s piece. So he followed his brother Matt to Brown. The university then, as now, was particularly known for its deep roster of experimental writers, from the novelist Robert Coover to the poets Michael Harper and Keith Waldrop, both of whom have won the National Book Award.

Lerner started out studying political theory and his first poetry class was with Harper, of whom he was terrified. The modus operandi was hands off. “They didn’t really teach, you know?” he says of the Brown faculty. “They were just kind of examples of living artists who had opinions, and you would read books that mattered to them.”

“I saw the Waldrops read,” he says referring to Keith Waldrop and his wife Rosemarie, who is one of the most prolific and important translators in post-war America. “And I was like, who is this weird, wizardly couple and what is this avant-garde nonsense that also has a kind of power over me?…They had this house, which was incredible — I mean, they let everybody go there, and when you’re an undergrad you can pretend to be a writer, and they would listen to you and be non-judgmental and act like you had something to say.”

In his third year, the wizardry rubbed off, and in one night Lerner wrote ten sonnets. They became the basis of his first book, The Lichtenberg Figures, a series of playful and aggressively associative fourteen line poems that zoom between the language of intimacy to advertising to the apocalypse. “Could this go/on forever in a good way?” one poem asks in a grim way.

* * *

BY THE TIME The Lichtenberg Figures was published, Lerner was out of Brown and had decamped to Spain, where he was spending a year on a Fulbright. “It was a mixture of contingencies and desires,” he says. “I wanted to learn Spanish, but I also wanted to go to Morocco and Portugal; I had been to Spain before a couple of times. I was interested in the way the Spanish Civil War had been such an international catalyst for a literary left.”

Lerner’s time in Spain was similar to and different than Adam’s. He did spend a lot of time going to museums and being confused, but his style of writing fiction isn’t necessarily life writing, like Adam’s. “I’m more interested in what’s left out,” he says. “I think of the Adam Gordon character really as a kid…And I have a tenderness towards him because he shares some of my anxieties. He’s a version of me even though there are huge differences. And I think of him as this kid kind of testing out his relationship to his art and thinking through his parents’ mortality.”

In fact Lerner spent a lot of his time in Spain alone writing his second book of poems, Angle of Yaw, which takes its title from the angle of a spacecraft’s ascent when seen from above. The submerged political critique in The Lichtenberg Figures becomes externalized in its successor. “All across America, from under- and aboveground, from burning bulginess and deep wells, hijacked planes and collapsed mines,” runs one of the book’s prose poems, “people are using their cell phones to call out, not for help or air or light, but for information.”

“I wasn’t aware that I was writing a novel,” he says of that period…”I think it’s useful to say, I’m not doing whatever it is I’m doing in order to avoid a certain kind of pressure.”

When Angle of Yaw came out Lerner was living in Berkeley, California with his wife Ari, who was working on a Ph.D. in education. When she finished, they moved to Pittsburgh for teaching jobs, bought a house, and for the first time Lerner began to feel restless for a new form. An essay he was writing on Ashbery and poetics kept growing and expanding. “I wasn’t aware that I was writing a novel,” he says of that period. “I was resistant to the idea that I was writing a novel for a long time. I think it’s useful to say, I’m not doing whatever it is I’m doing in order to avoid a certain kind of pressure.”

Lerner was less interested in remembering the time, than in characterizing the oblique nature of experience against the backdrop of larger forces. Ashbery, whom Lerner refers to as the enabler and threat, is like the book’s godfather. “He has that phrase that I thought about a lot in my novel, the experience of experience. His poems aren’t about particular experiences. They’re the experience of experience, which is the kind of definition of abstraction.” In many ways Leaving Atocha Station approaches Lerner’s time in Spain with a similar refractory power.

The novel also tries in its own way to reclaim the form’s radicalism. There are photographs throughout the book, poems, an extended chat message sequence between Adam and his friend Cyrus, who witnesses a drowning in Mexico. “You know, like Moby Dick — it’s gonna have a play, and it’s gonna have whaling textbooks, and it’s gonna often be written in iambic pentameter,” Lerner says. “And that heteroglossia of the really ambitious, experimental novels appeal to me even though the books I’m writing aren’t anything like that, obviously.”

One of the strengths of Leaving Atocha Station is how it absorbs these radical impulses without compromising narrative shape and speed. Upon publication the book was an immediate critical success. It wound up on a dozen end-of-year lists, has sold somewhere in the neighborhood of 30,000 copies after a small paperback first print run, won the Believer Book Award, and is fast becoming a secret handshake among young writers wrestling with feelings of political frustration and guilt over their seeming inability to say something new about that frustration.

Jonathan Franzen, who was one of the books early proponents, admires it still for its attempt to ground anxiety within a broader context. “Politically, what impressed me about it was its tangential approach to the bombing at Atocha Station, which shadows the whole book and adds — to the misery of a narrator whose native anxiety is so intense that it fosters extreme self-involvement and demands almost ceaseless self-medication — a miserable awareness of his American parochialism amid global political turmoil,” Franzen wrote in an email. “In that sense, the book is kind of a highbrow version of Girls: both of them critique privileged American self-involvement precisely by reveling in it.”

* * *

IF THERE HAS BEEN ANY resistance to Leaving Atocha Station, it comes from the perception of self-absorption being the topic rather than the delivery mode of ideas. Lorin Stein, the editor of The Paris Review, which has published Lerner’s poetry and sections of his second novel, 10:04, is surprised of the mislabeling of Lerner’s work.

“It surprises me that critics so rarely describe Ben as a political novelist,” Stein says. “His books aren’t just deeply engaged with politics — they raise the question how serious or funny a realistic American novel could be that *didn’t* notice changes in the political and economic landscape (or the landscape landscape, for that matter).”

Lerner seems to agree with this assessment of not just realism, but the novel in general, and what it requires in today’s America. “It doesn’t seem right to write a novel set in the contemporary that isn’t shot through with all this craziness,” Lerner says.

More important, however, this blending — of perception and politics — comes right out of how Lerner sees the world in real life. In the wake of Leaving Atocha Station, Lerner and his wife returned to New York, and as he walked around he realized he had all the inspiration for craziness in front of him.

“There’s the remaking of the city in the image of finance where you feel like wherever you go you are already there. And then there’s climate change, but the uncanny way in which it’s everywhere and nowhere if you’re in a position of privilege. You know, California’s out of water but you can still get your avocados at the co-op for a while. So this gap — the question of, it’s everywhere but where is it experienced? Where is the locus of experience of all this galvanic change?”

All of these questions and more are poured into 10:04, Lerner’s most recent novel, which on the surface has a lot of similarities to Leaving Atocha Station. The main character is an unnamed writer who has just signed a large book deal following the surprising success of his first novel. The opening scene takes place on New York City’s High-Line, where the narrator celebrates with an expensive meal of octopus that have literally been massaged to death so he can eat them.

Very quickly, however, the novel detours from Lerner’s earlier work. Where Leaving Atocha Station skewered poetry and art for its impossibilities, and its narrator for his inability to connect, 10:04 meditates on what Lerner calls “places of possibility, amidst a system which is out of control.” The main character, who may or may not have a serious medical condition, agrees to help a female friend conceive a child on her own. He works at a Brooklyn produce co-op where he meets a Middle Eastern woman whose life has been buffeted by the course of History.

Where Leaving Atocha Station would burrow ever inward to Adam’s self-absorption, 10:04 moves consistently sideways into a new scene. Lerner describes these transitions as “passing the mic.” So a series of characters tell their stories within the story. Lerner talks about Virginia Woolf and modernism and the problem of dialogue before settling on a simpler explanation for this newer structure: “For me what’s problematic is the idea that you have perfect access to other minds.”

Even if the structure of 10:04 has solved Lerner’s narration problem — by turning the narrator from an orienting consciousness to a mediating one — a lingering issue of what can be told exists. “I don’t know how to write from a position that isn’t a version of myself,”Lerner says, “but I also don’t know how to write firm, unmediated lived experience with whatever that would mean.”

In many ways one gets the sense that Lerner believes deeply that these spaces are where the American polis can rebuild and work against the forces he has been writing against.

The novel threads a line between these mutually reinforcing problems by turning outward, by keeping moving. 10:04 is a walking novel, and almost all of it takes place in public spaces: on the streets, where the narrator walks, regarding the city, in bars racing to be more studiedly retro, in a school where he volunteers in helping a young boy, in museums where he takes the kid after school. In many ways one gets the sense that Lerner believes deeply that these spaces are where the American polis can rebuild and work against the forces he has been writing against.

“The co-op is easily mockable and full of shit,” Lerner says, still sipping on his tea, “and totally contradictory, but it also is a space where labor practices are better and where a story like this can happen because of this work, even if the work is also silly.”

The novel dovetails neatly with Lerner’s third poetry collection, Mean Free Path, which takes its title from a term in physics about the trajectory of particles that collide in space. The book collects a series of love poems that seek to create a space of love in an environment of violence and destruction.

“They are both Ari books,” Copper Canyon editor Michael Wiegers notes, remarking on how both are dedicated to Lerner’s wife, “as if he needs to address larger notions of empire and power in order to fully engage the language of marriage and the freedom to love without relying upon love’s more reductive, traditional idioms. The political opens a path for the personal, just as the personal urges him to engage the political.”

* * *

AS OUR CONVERSATION WINDS DOWN, it becomes clear Lerner will be spending a lot of his next year living this space, not just thinking about it. On the day we meet, his wife is exactly one week away from a scheduled C-section. She arrives to pick up Lerner for one final lunch as a couple before their life changes again. She is huge and beaming, and Lerner is apprehensive, if not skeptical of any pretense at wisdom.

“I experience it mainly as this huge betrayal of [our daughter],” he says, referring to their first child, Lucia, “even though it’s this great thing for her, because it’s really hard to imagine…loving another kid as much as I love her, and I can’t decide if it’s gonna be a whole other love, or if it’s one love that envelops them both. It’s some sort of fundamental problem of division.

“But I don’t know, it’s kind of an unreal thing to me, still. I think it stays unreal — I used to think the unreality was a sign of oppression or denial, and now I think the unreality is actually an attribute of the experience.”

After things die down, he has a notion of another novel. It’s growing inside of him like a dream. “I’ve written some things,” he says, “and it’s not that I think they’re bad so much as I don’t think they’re parts of anything. They’re more like sketches. Like I woke up and I was like I have an idea for a novel, and then I realized that my idea was just that I would like to have a novel.”