essays

A Complicated Faith: Alex Mar & Leslie Jamison Discuss Witches of America, Spirituality & Writing…

A

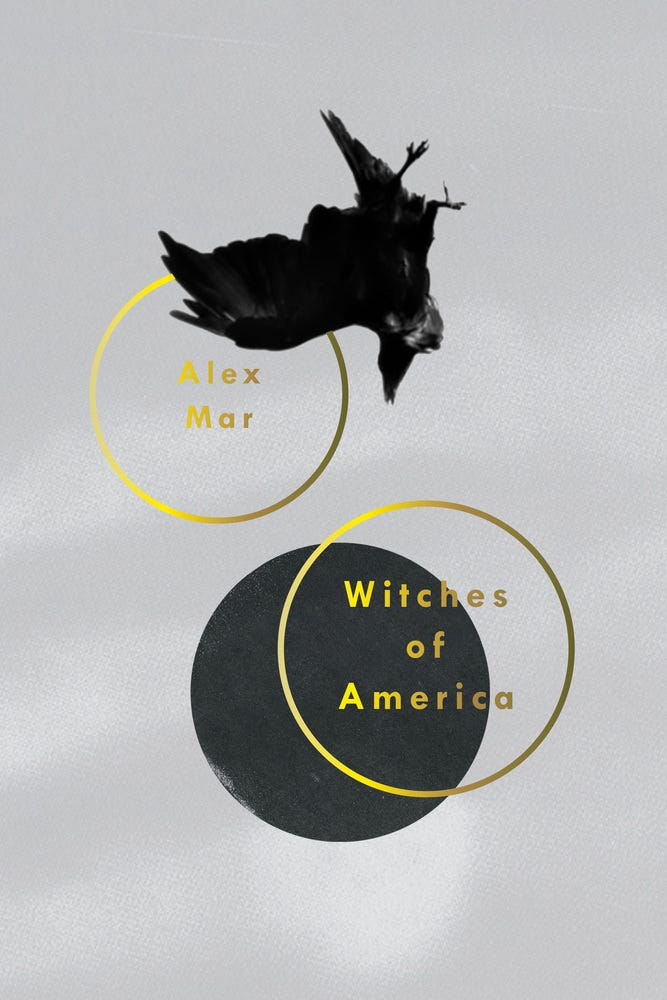

Leslie Jamison, the best-selling author of The Empathy Exams, recently joined Alex Mar at New York City’s Housing Works to discuss Mar’s first book, Witches of America (Sarah Crichton Books 2015) — an intimate, immersive account of present-day witchcraft all around this country. (The book was recently included in the New York Times’ list of Notable Books of 2015.) The two writers discussed Mar’s debut, their shared obsessions, and some of the stranger challenges of writing non-fiction. What follows is a slightly revised and edited version of their conversation.

Alex Mar will be reading — along with Alexandra Kleeman,Melissa Febos,Angel Nafis, and Lincoln Michel — as part of Electric Literature and The Rumpus’s holiday event at Housing Works next Tuesday, December 15th.

Leslie Jamison: At one point in your book, you talk about mixing the “me” up with the “them,” and I’m curious to hear you talk about how you got mixed up in this. In particular: how did you decide to make your journey part of this book? To not just be a receded observer, but to let yourself move through these worlds as a real character, to make that journey part of the story?

Alex Mar: Actually it’s funny — when I first pitched this idea to my publisher it was very much with the sense that I would use myself as a light framework. Like, okay I will guide you into this world, but otherwise I’m really going to have a minor presence. And not that long into writing it and having these experiences, I sent an email to my editor saying, more or less, “I think you should know, I’ve already gotten in too deep.”

I just felt like it was disingenuous to pretend that my interest in witchcraft was neutral.

I just felt like it was disingenuous to pretend that my interest in witchcraft was neutral. I think really for anyone the word “witchcraft” has this kind of primitive, gut-level impact that goes back to childhood — folktales, fairytales, movies that you’ve seen. And on my side, I was raised partly Catholic but also politically liberal and a feminist and in New York City — and that was messy, ideologically. As an adult, I ended up with the sense that there wasn’t any organized religion I could commit to, while feeling, at the same time, that there was some big mystery out there that I wanted to get a handle on. Is there some way to get closer to that? So I realized that was the reason I wanted to write this book in the first place. And then I just dove in.

LJ: And I think what you’re talking about — this sort of intuitive, strongly-felt sense of there being a larger mystery — that becomes this shared terrain between you and the people you’re writing about, which I think charges the book with a different kind of energy than you as an observer, standing back, looking at these fringe communities and offering them to us. I mean, you’re in them, and you’re taking their questions and their quests so seriously, which is part of why we, when we read it, take them seriously too. It speaks to something primal in all of us.

AM: I hope so! That was the idea. I wanted to use myself as a bridge. I don’t know who the mainstream “average” American reader is, but I’m assuming that that person doesn’t have experience in the Pagan community, hasn’t experimented with witchcraft, and all of this is going to seem kind of alien and exotic. So how can I use myself to communicate “My starting point, on the surface, seems really far away from the people in this community, but come with me as I show you the ways in which that distance is a lot shorter”? I just felt that was the best approach.

LJ: Well, the distance really gets collapsed. Not to give too much away, but there’s a point when you find yourself camping in a swamp with some gigantic banana spiders. I mean, your mind, body, and spirit really get implicated in this, and that makes the journey compelling in this very visceral way. I’m curious what those relationships are like. A woman named Morpheus is a really big part of the book — she’s a Feri priestess — and your relationship with her is part of the story. How did these relationships develop? How did you come to a place of trust with Morpheus?

AM: Yeah, this is obviously a big part of being able to write about people who are alive and walking around on the planet independently of the writer. You can’t relate to this at all, Leslie! [laughs] But, basically, I made a documentary about five, six years ago called American Mystic, and it was meant to be intertwining portraits of three different characters: people in their twenties in very far-flung parts of the country who were engaged in different fringe religious communities that were mystical in some way and that really set them apart from the mainstream. I really liked the idea of showing another piece of what faith in this country could look like, and also the higher cost to your mundane life if you’re part of a community that really sets you apart, that a lot of people can’t relate to.

…they’d cleared out this plateau and dragged these huge standing stones with the help of a bunch of fellow Pagans from all around the Bay Area to create their own henge. A stone henge in Santa Clara County…

So, over the course of about six months traveling around the country trying to find the right people for this film, I met this woman Morpheus out in Northern California. She was, at the time, living way off the grid on a hundred acres of extremely wild land in Santa Clara County. She and her then-husband lived in this double-wide trailer on one part of the property, and if you hiked up this hill, they’d cleared out this plateau and dragged these huge standing stones with the help of a bunch of fellow Pagans from all around the Bay Area to create their own henge. A stone henge in Santa Clara County — and none of their neighbors knew about this.

Anyway, I really admired this sense of dedication because, in her mind, she was creating a sanctuary. People from all around the Bay could come and practice witchcraft. They could just get in touch with her and they could have these rituals on the hill, under the moon. So we talked, and Morpheus had this wonderful sense of humor. She was really no-bullshit, and just a goofy, low-key person — and then she would dress up and prepare for ritual and be completely transformed. I was just so impressed by her magnetism, and her level of dedication. I like that phrase “walking the walk” because you know it when you see it, right? When someone is “walking the walk.” And Morpheus was.

The thing about a documentary, however, is there are always cameras in the way, and you can’t achieve a real intimacy, I think, when there are cameras in the room. So when filming wrapped and I was back in New York, I realized that I had left something behind — a missed opportunity. I really wanted to step into circle with Morpheus and her people and try to understand what it was that drew me in in the first place. Now that cameras aren’t rolling anymore, what is this to me? And as someone who is fundamentally a writer, I then thought, “Ok, well, it’s a writing project. That’s why I’m interested. It’s something intellectual.” I don’t know if you have this, where you feel like there are themes you’re drawn to, certain situations or individuals, and then you kind of have to double back and be honest with yourself about why you’re there?

LJ: Yeah, well, I certainly know the dynamic of doubling back on the same kinds of recurring questions or preoccupations. I would always joke with my editor that my next book was just going to be called Even More Empathy Exams. You find yourself exploring the same topics — you’re not done with them. It’s hard to be done with them. I think that feeling of asking yourself “Why am I interested in this thing?” is such a compelling layer of the process to me — as the reader — and it sort of feels like an inevitable layer of the process for me as a writer.

A piece I wrote about Morgellons disease came to mind for me at certain points when I was reading your book — in terms of writing about a community and balancing skepticism and respect. I’m at a conference in Austin with a bunch of people who understand strange, unidentifiable stuff to be coming out of their bodies. Why am I here? What’s my stake in this? What’s shared between me and them? What remains alien to me about their experience? All of those questions. Getting into those questions, not backing away from them — that’s how I get into the thick of what matters and come clean to readers about my own presence in the room and what that presence is about. And that’s certainly one of the plot-lines of this book, you constantly asking yourself “What am I seeking from being in this space?”

AM: Definitely.

I just think that’s the way humans work: you identify with someone for whatever reason — you like their voice or little details you find out about them — and that allows you to relate to them.

This also makes me think of the way in which you and I both blend genres in our approaches to nonfiction, and how people have different ideas or emotions around that. For instance, I’m a very strong believer in using the first-person as a way in, because it works for me as a reader. I just think that’s the way humans work: you identify with someone for whatever reason — you like their voice or little details you find out about them — and that allows you to relate to them. And they take you into this universe that for you seems a million miles away from your own experience, but now you’re relaxed and you’re willing to go along. And before you know it…

I have a dream scenario in which there’s some conservative Christian reading this book [laughs] who I’ve made feel comfortable in some way, and then they’re immersed in Aleister Crowley’s Gnostic Mass, and before they know it they have a different perspective on what they’re willing to explore.

LJ: To speak briefly to your fantasy about the conservative Christian reader, I feel like — I don’t know how many people saw that image going around that’s Claudia Rankin’s Citizen at the Donald Trump rally, but —

AM: Oh my God, yes.

LJ: Yeah, so I feel like maybe Witches of America is next —

AM: At a megachurch!

LJ: Yeah.

AM: Great, I love it.

LJ: At various points, I’ve felt a real range of reactions to what happens when the story of the self is brought into the same chamber as the stories of others — in relation to my own work, but in relation to other people’s work as well. And I think that for some people that combination feels like an honest portrayal of what happens when people have some kind of encounter — that two consciousnesses are present, and so there’s something to be said about both of those consciousnesses in the piece that results. That’s certainly how I feel and how I write, but I also think that that kind of blending of genres, of memoir and reporting, can also raise this feeling of the self as an intruding presence, you know?

AM: Like “I’m so fantastic, I’m in this scene.” Oh God.

LJ: Right. It calls to mind Mystery Science Theater 3000, with the two little robot silhouettes in front of the films.

AM: I never saw that coming! I never saw you dropping Mystery Science Theater. This is amazing.

LJ: I never thought that our conversation would have taken me to this point, but here we are. Sometimes I think there’s this obnoxious version of that, that’s the way in which people see the self of the reporter of the piece. Where you’re this little robot silhouette that’s threatening to block out what’s really of interest.

AM: Right. Like “What right do you have to be there also?”

LJ: Yeah. But I think, as opposed to quietly squirreling away the possibility of some kind of transgression, that approach makes visible the dynamic — something that’s not about either person in isolation but about what happens between them, or the magnetic energy between their stories. Allowing both voices into the frame reckons with it more openly. I like to be able to ask these questions more explicitly, about: what right I have to be here, and what’s my stake in this? What’s my relation to this?

AM: And your book obviously grapples with that in a major way. For my money, I really do think it’s an incredibly honest approach.

In the case of someone like Morpheus, who’s a central subject in the book, it almost felt like a collaboration. But it’s a really delicate thing — and I know you’ve encountered this too. When you write nonfiction, people will say, “Sure, you can write about me.” But this is the touchiest terrain. I think the human impulse — for any of us — is to immediately think “You’re telling me that my life is interesting, that my stories are important, that people want to know about my life.” You feel validated in a way. And very few human beings know writers really well, are also journalists, and understand that when someone says, “I’m going to write about you” they may include details that to you feel incidental or unexpected. They may see you differently than you see yourself. So the relationship is delicate; it’s a balance that way. And I think any journalist or nonfiction writer would tell you the same thing if they’re being honest.

LJ: That’s something that both of us have articulated in different ways in our work, a desire to believe fully in what our subjects believe, the desire to align ourselves with the beliefs of someone, the frustration of never quite achieving that total alignment. I know, for me, some of it comes back to quite primal aspects of my personality that have to do with being a people-pleaser in a job that could not be more antagonistic to people-pleasing. I think writing about the lives of other people is not the right line of work for a people-pleaser — but it is the work that I seem to have found myself in.

When you narrate the life of another person in whatever fragmentary way, there’s some violence, or some possibility of violence.

When I spend time with somebody, especially somebody who’s in some condition of vulnerability or some condition of pain, I want so deeply for my writing to be a positive experience for that person, for him or her to feel represented by me in a way that is wholly good. But, for all the reasons that you were speaking to, Alex, there’s something impossible about that dream. When you narrate the life of another person in whatever fragmentary way, there’s some violence, or some possibility of violence. Even if there are no ill intentions, there’s a real possibility of violence in the inevitable gap between self-perception and somebody else’s perception of you. So in those moments in my writing when I speak to that desire to believe fully what one of my subjects believes, I’m kind of mourning that gap, or I’m mourning that violence, or I’m trying to acknowledge what’s happening in that space where I’m presenting another life but I’m not fully standing at the same angle as my subject — I’m not seeing them in the same way as they’re seeing themselves. So it doesn’t solve the problem, but sometimes I reach a point where I feel like I have to speak to the problem or bring the problem onto the page. So that’s sort of why and how it comes up for me.

AM: Honestly, this is really the crux of the matter.

But one difference between something like your essays and my book is this: this is a book about faith, and a book in which I became an active participant at a certain point. So for me it was less about “Do my beliefs align with the beliefs of everyone in this situation?” and more about “Am I going to connect here?” Seeking out that connection. Like in the way that, if you were a practicing Catholic, you might not say, “Okay, am I going to relate to the priest?” but rather “Is there something in this specific religion that’s going to give me some answers or point to a door that might open slightly for me?”

If you write about a religion, and you take part in a ceremony, you’re not doing some sort of scientific, sociological documentation…Because spirituality is inherently totally subjective.

And here’s the thing: you can’t go and write in an objective way about witchcraft rituals. That would be absurd. If you write about a religion, and you take part in a ceremony, you’re not doing some sort of scientific, sociological documentation. I mean, obviously that’s been done — but I think it’s a little bit bullshit. Because spirituality is inherently totally subjective. I can’t tell someone, definitively, what it feels like to sit in synagogue; I can’t tell someone what it feels like to take part in a Catholic mass. So I wanted to embrace that all the way. There are these descriptions of rituals that I wasn’t there for, but most of them I was present for. And hopefully, in those scenes, I raise questions for the reader, like “What would my reaction be to this? Can I imagine myself in that room? Would I have had the same experience? What she’s describing is compelling to me, but I don’t have the same hang-ups.” I think there’s room for that in there, right? And the reader can feel what is was like to stand in that space, and at the same time they’re with the narrator so they feel a bit safer.

There’s been this extremely mixed reaction to my book from the witchcraft and occult community online — depending on where you explore on the Internet, in different chat rooms and whatnot, or my Amazon or Goodreads pages. Some of the people commenting are open about not having read the book. It’s generally a strong reaction — one that I perhaps naively didn’t anticipate — along the lines of: what right do you have to write about this community if you’re not someone who’s a lifelong devotee? If you’ve been trained in a particular witchcraft tradition, initiated at x number of levels, and been at it for decades, then that’s a situation in which you have permission to write about this material and these experiences. And I strongly disagree. It’s certainly complicated — but I think that’s like saying that if you have any doubts, or if you’re exploring as a spiritual person, you don’t have the right to write about faith. And I just — The thought of that makes me really lonely.

There’s this false idea out there that faith and belief is some black-and-white thing. You’re either an atheist or a complete convert. And in this culture in particular, people really love a conversion narrative in which you find God! And then you write a book about it! And that’s fine. But I really wanted to make this book, at least in part, about this gray area. So many people in my life, that’s their experience: they don’t know where they land, but they feel compelled to be searching in some way. And maybe by writing about that it becomes less of a lonely situation in terms of how we’re able to talk about religion and what the meaning of our lives is and all that lofty business. [laughs]

LJ: I love that. It feels so true to my experience of your book, as well as my experience of all the ways that people move through the complexities of spirituality, that so many of us live in a “gray area.” I want to talk more about that. Because, like you said, it’s complicated to write about faith, and I’m interested in what set of competing desires or competing impulses or fears or anxieties or hopes were running through your mind when you thought about how to both do justice to what felt inspiring and beautiful to you from what you saw in these communities while also operating with some degree of questioning and skepticism. How were those impulses towards respect, on the one hand, and skepticism, on the other, moving through you when you were writing?

AM: Like, the question of how to strike a balance? It’s so tricky. I definitely tortured myself over this a lot over the last three and a half years — that’s about how long this book took, between the writing and the research. There’s a number of books out there that are written for the Pagan community by the Pagan community — but they’re written in a sort of insider lingo, or they’re how-to books in some way. So there’s really no desire to reach out to the mainstream with that kind of book. Margot Adler’s Drawing Down the Moon, back in the seventies, was an important crossover book about this community — but that was very deliberately a survey, with no narrative arc. A very different project.

I looked at some of the stories of this very recent history, of the Pagan movement, which in this country only goes back to the 1950s — which is unbelievable! You can trace it back in a very specific way to the south of England. And there were these incredible individuals who were only recently deceased or are still alive, people who were pivotal in the spread of Paganism, and community authors wrote about them with so much reverence — it was almost like they missed a sense of amazement at how these people had had the balls to do the things that they had done, to go “Okay, I’m a poet who’s mostly blind, living in this small town in Oregon, and I’m going to secretly train with a coven of Dust Bowl refugees that I’ve encountered. And now I’m going to train students of my own at my house, and I’ll keep it secret that I’m teaching renegade witchcraft out here in the 1940s.” Are you kidding me? Completely amazing! But, from within the community, many are looking at these people as prophets, in some cases, or as sacred individuals. And I think that runs the risk of —

I think it’s wonderful to write about how complicated an individual is, even the head of a witchcraft tradition.

Sometimes I think about how, when you go to someone’s funeral service, and that person was a major character and kind of a pain in the ass in a wonderful way, no one says that out loud. I’ve always felt that there was something tragic about that. I think it’s wonderful to write about how complicated an individual is, even the head of a witchcraft tradition. So I felt that was a balance that I could bring while still being respectful. In telling someone’s story, I could simply acknowledge, “Holy crap, that was an incredible circumstance for someone to be in.”

In terms of my own involvement, I think I very deliberately put myself in a number of embarrassing and vulnerable situations. I wanted to be as open as I could about my whole range of feelings about eventually choosing to train in witchcraft, and my relationship with my witch-teacher in Massachusetts, and the idea of being affiliated with a coven, and going to meet the coven on a certain date at, like, a castle in New Hampshire. “What is going on? I feel conflicted — how am I supposed to feel here?” And, as a writer, you choose to reveal specific things about yourself to signal to the readers “Hey, I’m exposing myself. There are embarrassing things that you should know about me. Let’s just get them out on the table.” And perhaps not all readers understand how self-aware and deliberate that choice is. That the writer is actively, strategically extending her hand in those moments.

People don’t just exist in one dimension, in your book, whether that’s a mundane dimension or a spiritual dimension — you’re asking them to exist in both. And that makes it so much more stereoscopic.

LJ: Yeah. Well, that question about the revelation of the self is so never-ending, for both of us. I often bring myself into the frame in order to complicate what I’m saying about someone else; almost a way of stopping myself from making an overly simple determination. But part of what I love about the portraits of the people in your book really has to do with that urge toward complexity, that desire to come out and say, at a memorial service, “Here are the ways in which this person was a pain in the ass when they were alive.” Not that you’re making everybody into — I don’t even know how to make that plural — pains in the asses? But we get people in their fullness. Like, we get that this guy was trying to spend time with his six-year-old daughter after he’d split with their mom — we get that vision of him and we get the vision of him in an occult mass. We get your teacher as your witchcraft teacher, and we get a vision of her at home raising her kids. People don’t just exist in one dimension, in your book, whether that’s a mundane dimension or a spiritual dimension — you’re asking them to exist in both. And that makes it so much more stereoscopic.

AM: Oh, I like that: stereoscopic. For instance, there’s the moment in which I decide to start training, maybe halfway through the book. I write to Morpheus — because at that point we have this friendship and I feel like I can trust her — and I say, Okay, I guess I want to train in witchcraft. How do you do that in 2012, 2013, whenever it was? And she sends me someone’s email address. And I thought, “What? I email this woman and she becomes my personal Jedi master, my mentor in this secretive, ecstatic Feri witchcraft tradition? Um, okay. Is that disappointing or — ?” But I realized that was a childish reaction. I wanted some sort of fairytale version of things when actual priestesses are sitting at home thinking “I just don’t have time! If you want me to pass on the tradition, let’s be efficient about it. We’ll e-mail. You fill out this form. We’ll schedule a call. And if you make it past the phone call, well, then we can go somewhere with this.” And actually at some point my teacher said, “I want you to know that this is like grad school. So you should be prepared to do some serious reading.” [laughs] And I loved learning to accept the mundane aspects of it all. I mean, that’s life! That’s real. That’s what made it more than a lot of fairytale hocus pocus. This is a living, evolving, religious movement. And, you know, a witch usually still has a job. And she picks up her kids and shops for groceries and plans the ritual for her coven that weekend…

LJ: Yeah, the book ultimately offers both. I mean, we get everything that some part of me, when I started reading it, was hoping for. The naked priestess! The necromancer! All that. But we also get the email exchanges and this process that looks maybe more pragmatic than what we had in mind. The fact that there’s room for all of it is part of what kept surprising me.