Books & Culture

The Migrant Experience: From Page to Screen

by Sarah Jilani

Literature has undoubtedly fed into cinema in ways both mutually enriching and somewhat frustrating for fans of exclusively either one or the other. Luckily, rarely are storytellers and story-lovers willing to divide the two, despite their differences. In mainstream Hollywood or “First Cinema,” recent decades have seen producers lean heavily on adapting existing material, as original screenplays seem increasingly shelved in favor of films based on bestselling fiction, graphic novels and re-worked classics. Simultaneously, however, arthouse and independent film have slowly but surely moved out of festival circuits; from being seen, critiqued and distributed amongst a certain (rather white, male and privileged) slice of the art world, to the screens of a young, multicultural audience through digital on-demand film platforms such as Mubi, FilmDoo and Festival Scope.

It would not be a far stretch to say this kind of repositioning reflects a lot of the increasing diversity in themes, voices and human experiences in the subject matter of films adapted from literature, too. In fact, if the 20th and 21st centuries have seen film of all art mediums grow at a singularly popular, global rate, they have also been decades marked by unprecedented amounts of human migration, alienation, assimilation and re-orientation. After all, art reflects life — or so they say. The memoirs, novels, autobiographies, short stories and poetry borne of these collective experiences of home-making and belonging, leaving and arriving, are as central to literary production today as ever. As film continues to speak to us with the kind of visual power that transgresses borders, language barriers and increasingly (thanks to newcomers disrupting old distribution channels) challenges of access, our experiences of migration and movement are becoming a popular genre of their own on the big screen.

These 5 must-see films bring to visual life literatures that recount lives and histories marked by emigrations, exiles and new beginning, taking the text to new audiences and showcasing the communicative power of film and literature working in creative tandem.

The Reluctant Fundamentalist (Dir: Mira Nair, U.S.A, 2012) — based on The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2007) by Mohsin Hamid

Pakistani author Mohsin Hamid’s 2007 novel is a snappy, penetrating and multi-layered read, and Indian director Mira Nair handles it well in her 2012 adaptation of the same name, The Reluctant Fundamentalist. Hamid’s novel gets much of its zing from the second-person narration that builds a tension akin to Albert Camus’s The Fall (1956), the rich psychological undertones of which are lost in Nair’s more sweeping, action-oriented version. Riz Ahmed stars as Changez, the smart young Pakistani emigré, fresh out of Princeton and straight into an elite Wall Street valuation firm. With ambitions for the future and an American upper-class photographer girlfriend Erica (Kate Hudson), Changez relishes his culturally and socially mobile persona in cosmopolitan New York. However, after the World Trade Center attacks, his life and mind undergo a slow-burning transformation. Met with increasing suspicion, prejudice and worrying news of his family’s safety in Pakistan, Changez returns to Lahore and becomes embroiled in dense political intrigues.

Black Girl (Dir: Ousmane Sembene, 1966) — based on La Noire De… (1962) by Ousmane Sembene

Sometimes dubbed the “African Brecht,” Soviet-educated Senegalese writer and director Ousmane Sembene adapted one of his own short stories into his first feature-length film in 1966. La Noire De… meaning “The Black Girl Of…” follows the story of Diouanne (Therese N’Bissine Diop), a young woman employed as a governess in a white, bourgeois French household in Dakar. First excited at the prospect of going with the family to the French Riviera for the summer, Diouanne soon finds her employers’ attitudes much changed in France, her chores more numerous, domestic and slavish, and her identity overwritten by her race. A true classic of African auteur cinema, Black Girl remains as effective as ever in its psychological exploration of prejudice, belonging and gender.

The Namesake (Dir: Mira Nair, 2006) — based on The Namesake (2004) by Jhumpa Lahiri

Taking us from Kolkata to New York, The Namesake is a touching drama following Ashoke and Ashima Ganguly as they migrate to the States from India. The nuanced difference in the second-generation migrant’s experience is explored through their son Gogol (named in half-seriousness after the famed Russian writer). Growing up wanting to be a typical American teenager, Gogol acts hostile to his parents at times and fiercely feigns indifference to his Indian cultural roots. Changing his name to Nick and leaving for Ohio with his American wife, as time passes Gogol begins rediscovering his roots in small personal ways, eventually deciding to travel and narrating the story that in fact is the film itself. Witnessing the difficulties and joys of more than just physical departures and arrivals, we are won over by Nair’s quiet but moving directorial touch in an honest depiction of life going on, despite upheavals and the complex inner states engendered by our need to belong.

Brooklyn (Dir: John Crowley, 2015) based on Brooklyn (2009) by Colm Tóibín

Brooklyn follows Irish wallflower Eilis Lacey (Saoirse Ronan) as she leaves for 1950s New York in search of a better life. By a much-celebrated Irish writer often acclaimed as following in the footsteps of literary names such as John Banville, Brooklyn the novel has a greater depth and slight darkness than its new film adaptation: nevertheless, it delivers on providing an affecting and honest narrative of a different kind of migrant experience. Some emigrations can seem voluntary or for personal betterment, as it could be said for Eilis, who makes a career move — yet the nuance of her situation is one many today could relate to. Sometimes, voluntary migration can be much like forced migration: that is not to say the story compares Eilis’ troubles to someone fleeing war-torn countries, but she is still someone without much choice, in that her home lacks the prospects and life she seeks. Transitioning to American life alone not only brings out the confident woman in her, but also has Eilis redefining ‘home’ at a time when its stability meant that of women’s place, too. From homesickness after arrival to eventually finding joy, love but also a divided self, Brooklyn is a genuinely heartfelt story with a believable trajectory and heroine at its center.

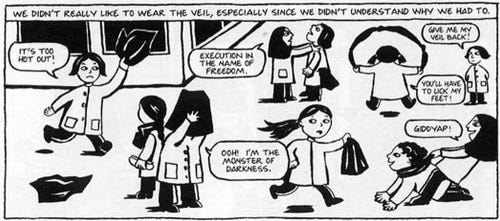

Persepolis (Dir: Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud, 2007), based on Persepolis (2000) by Marjane Satrapi

Based on an autobiographical graphic novel that tells the coming-of-age story of its author, touching upon life in pre- and post-revolutionary Iran, adolescent angst, moving abroad and growing into multicultural, defiant and independent young adulthood. Winning the Jury Prize at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival and narrowly missing out on the Oscar for Best Animation, the film garnered criticism from the Iranian government and acclaim from the international film circuit in equal measure. A playful and visually fantastic animation in the style of Satrapi’s original graphic novel, Persepolis’ precocious, young and imaginative protagonist Marjane has both an acerbic wit and a big heart — unsurprisingly, this makes her narrative of political events, life’s milestones and her not-so-ordinary family upbringing a delight to watch. Fearing her arrest for her outspokenness, Marjane’s parents send her to a French boarding school in Vienna for her safety. Feeling isolated amongst people whose cares seem superficial compared to those of friends’ at home, frustrated with the double standards of the Catholic nuns she lives with, and disappointed in her Austrian boyfriends, Marjane tries to survive in her new surroundings by recalling her grandmother’s advice on retaining her integrity. However, her experience of migrant life is one of anticipating the holidays so she can return home, and feeling helpless when she leaves. Eventually, when Marjane returns to a new and very different Iran, she realizes her experience has taught her to survive in difficult situations with her rebellious spirit intact. It is an adaptation that is inspired, simple and frictionless in its transformation of the source material, effortlessly juggling comedy and drama while reminding us goodbyes and returns are a part of all of our stories.