essays

A History of the Christmas Story: Not Altogether Christmas but Christmas All Together

by Kate Webb

Winter darkening brings its own intensities: snowdrifts on rooftops, red berries in the trees, and for the lucky few, maybe a pub fire roaring in the grate. As the nights draw in and the season’s grand finale approaches, many of us still brighten our world with carol singing, high street lights and Christmas stories — key ingredients in the mix of paganism, consumerism and religion we call Christmas. The stories we read now first appeared 150 years ago. Dickens established the modern form, publishing one in most years of the mid-nineteenth century, and soon everyone from Anthony Trollope to Louisa Alcott was trying their hand. Few could resist the temptation of sentimentality, and a reputation for the maudlin persists. “The very phrase Christmas story had unpleasant associations for me,” says Paul Auster’s narrator in “Auggie Wren’s Christmas Story” (1990), “evoking dreadful outpourings of hypocritical mush.” Despite this, Auster understands that though the Christmas story is a low form (a literary ‘turn’), it sets challenges few writers would run away from, which is why so many grandees (Tolstoy, Waugh, Spark, Updike) have bothered with it. Part of the attraction is that Christmas is one of the few events still bound by tradition, making the Christmas story — a thing of retrospection and repetition — peculiarly literary and self-conscious.

Christmas is one of the few events still bound by tradition, making the Christmas story — a thing of retrospection and repetition — peculiarly literary and self-conscious.

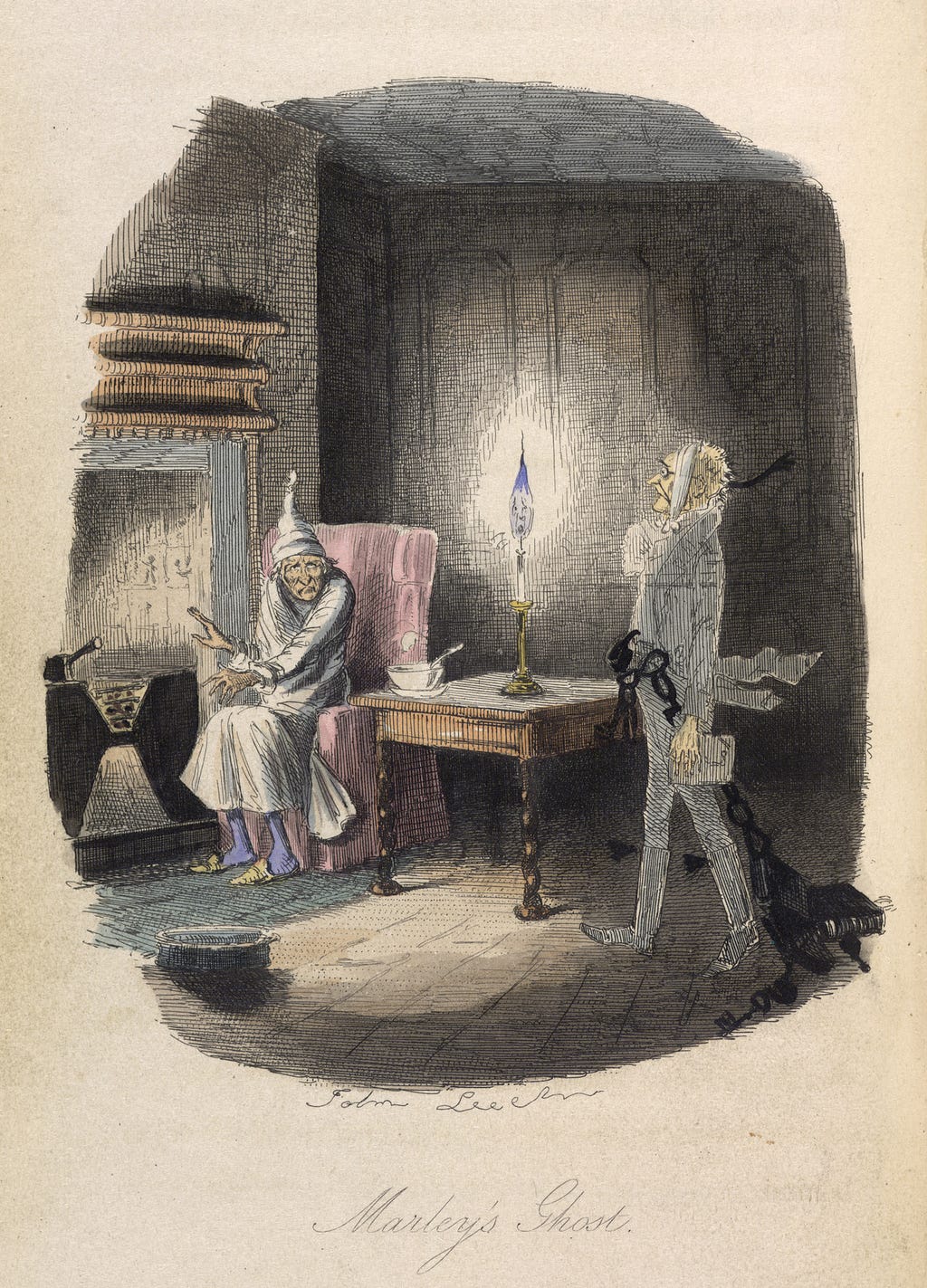

Christmas present, Dickens saw, always contains Christmas past (explaining why so many of its stories are inhabited by ghosts or children), and this gives rise to a moment of reckoning. In A Christmas Carol (1843), the accusation leveled at Scrooge is one of stinginess; the counting house turns men into creatures of rote, incapable of empathy or conviviality. Spiritedness is what matters, and even the poorest can revel in festivity. So on his ghost-flights Scrooge encounters miners, lamplighters and lighthousemen, all “blithe and loud” as they dance round fires and tell tales to one another. It was this lost spirit of Christmas that interested Washington Irving, whose sketches of customs that were dying out in England had first inspired Dickens. Irving included among these a lament about the disappearance of the Lord of Misrule — a figure older than the Anatolian Saint Nicholas, older even than the Dutch Sinterklaas or Nordic bearded elfman — who was outlawed during the English Civil War, along with the Christmas holiday and its twelve day riot of feasting and carousing.

No doubt it was Irving that Angela Carter had in mind when she wrote “The Ghost Ships” (1993), a fable about relations between the puritan New World and the superstitious old one. Even in Boston Bay, where Christmas was prohibited, citizens were still vulnerable to the witching hour. Into this permeable moment slip three ghost ships. One decorated in apple, holly, ivy and mistletoe. One fronted by a boar’s head, belching “swans upon spits and roast geese dripping hot fat.” And one carrying mummers and masquers, “large as life and twice as unnatural” (men dressed as women, bells jingling at their ankles) — the revenants of once Merry England. All three ships come sailing by and all are sunk by the puritans’ “awesome piety.” But something in their meaning will not be denied. As the Lord of Misrule falls into the Atlantic, he hurls a contraband pudding onto the shore. The next morning its plump raisins have scattered into the shoes of every child rising to pray in the “shivering dark.”

As the Lord of Misrule falls into the Atlantic, he hurls a contraband pudding onto the shore.

Inevitably, the struggle between Christianity and a barely-suppressed paganism is at the heart of many Christmas tales. Among the wintry Russians, Tolstoy and Chekhov produced stories in which Christian goodness prevails. But in “The Night Before Christmas” (1832), Gogol, writing in the folk tradition passed down to him by his Ukrainian mother, tells a wild tale that begins in the witching hour (literally, with a witch on a broomstick), where the devil gets his due. Gogol’s magic is not Christian (miraculous and didactic), but that of a trickster who steals the moon and hides it in his pocket. As in Dickens, a man is flown about by a spirit, but for the purpose of mischief-making rather than moral instruction.

A century later, Nabokov wrote two stories typical of his canon in their cunning and tenderness, while at the same time pinning the essential elements of the Christmas genre. “Christmas” (1925) is about a father visiting his country manor after the death of a beloved son, whom he remembers netting butterflies. When he moves one of his son’s pupae into the heat of the house it emerges unexpectedly, a rebirth as fantastic as the Resurrection itself. This is fiction as consoling and full of powerful magic as any religion. It is written wittingly, inside, and out of, tradition — Christian, rather than Gogol’s paganism — and, like the smartest of these tales, knows its place, even as it tries to usurp it.

Three years later in “A Christmas Story,” Nabokov conducted the discussion of a story’s “place” out in the open, pondering the fate of the imagination under tyranny and reconsidering the debate about puritanism. Wondering how to write fiction in a manner acceptable to Soviet Russia’s cultural commissars, an old writer, a novice writer, and a critic all discuss how Christmas can be viable in times that insist only on the real. Finally, the old man comes up with a story in which well-fed Europeans are mesmerized by a shop-window Christmas tree stacked with ham and fruit, all the while ignoring a body slumped “in front of the window, on the frozen sidewalk — ”. The sentence needs no completion: the winning formula has been found (decadent foreigners blind to the suffering of the poor). As one might expect from Nabokov, it is a knowing piece — the old writer struggling to describe Christmas in the critically-approved language (the “insolent Christmas tree,” the “so-called ‘Christmas’ snow”), and the critic, who writes for a journal called Red Reality, praising the novice’s depiction of peasant lust, but dismissing his portrayal of an intellectual because “There is no real sense of his being doomed…”

In the second half of the twentieth century writers continued to take the Christmas story apart, alerting readers to its dialogism; sometimes, as in Dylan Thomas’s unruly tale, “A Child’s Christmas in Wales” (1955), even granting them a walk-on part. Here, a memoirist channelling “distant speaking…voices” conjures a reader who queries his fantastic account of a time long ago when there were “wolves in Wales…and we chased, with the jawbones of deacons, the English and the bears.” Paul Auster’s tale comes less directly and innocently out of a folk tradition, but seems the most consummate of Christmas stories in the way it assembles and disassembles itself. There are multiple narrators and a story within a story; there is the “business about the lost wallet and the blind woman and the Christmas dinner”; notes to the reader about trusting the storyteller (“he knew exactly what he was doing”); lessons in the suspension of disbelief and fictional ‘truth’; and discussion of the “out-and-out conundrum” of the unsentimental Christmas story. Finally, there is a polite reminder to pay the piper.

For Grace Paley and Alice Munro the mystery is no longer a matter of miracle or spirit but a modern question of identity and doubt.

Other writers have reformulated the Christmas story by putting a new spin on the old tale. For Grace Paley and Alice Munro the mystery is no longer a matter of miracle or spirit but a modern question of identity and doubt. They find fresh perspectives with young girls as protagonists who speak distinctively in the first-person, though without a hint of Thomas’s orotundity or Auster’s complicity. Their stories, echoing the Teaching of the old story, are about education.

In Paley’s “The Loudest Voice” (1959), Shirley Abramowitz, child of the noisy Brooklyn street, is chosen to read the text in her school’s Christmas play. But she and her friends are Jewish immigrants and their involvement in a Christian drama creates tensions in a community divided in its views on assimilation. “This is a holiday from pagan times also, candles, lights, even Hannukah,” her papa says, arguing for his daughter’s inclusion, “So we learn it’s not altogether Christmas.” When the play is over, the parents debate in Yiddish, Russian, Polish. Why had so few American kids gotten big parts? “They got very small voices,” Shirley’s mother points out, “why should they holler? Christmas…the whole piece of goods…they own it.”

Munro’s heroine is too young to become a waitress so she takes a job as a turkey-gutter. “Are you educated?” is the first question anyone asks her in “The Turkey Season” (1980), and an education is precisely what she gets observing relationships in this family firm. She learns whose power is ostensible and who really runs the place; about the skill involved in dissecting a carcass; how seriousness and curiosity can overcome disgust (“Have a look at the worms…Now put your hand in”); even that there are some mysteries, “voluptuous curiosities,” such as the sexuality of her supervisor, which will not yield to scrutiny.

This one has a curmudgeon to match Scrooge — not in asceticism (she orders far and wide on the Internet) but in her refusal to get into the Christmas spirit.

In the twenty-first century, there has been a revival of the Christmas story, with examples from Jeanette Winterson, Will Self, A. L. Kennedy and Jackie Kay. One of the most attuned to the times is Ali Smith’s pointedly titled, “Do You Call That a Christmas Present?” (2008). This one has a curmudgeon to match Scrooge — not in asceticism (she orders far and wide on the Internet) but in her refusal to get into the Christmas spirit. What this woman wants for Christmas are comforters: wine and cake, socks and scarves; what she gets is a block of ice, a skeletal tree with dirty roots, a mad girl standing outside in the snow, serenading her. At first she is appalled, but her lover’s enthrallment to the season is infectious. Despite her cynicism, when a girl dressed as a boy soars through the air at the pantomime, she finds her face “wet with tears.” Soon she is watching Christmas films and singing Christmas songs. “Have yourself a merry little Christmas,” she hums and, at last, she is.

The whole piece is traditional as can be, hitched to “The Twelve Days of Christmas.” By the eighth day, she is “telling stories of Christmas past,” ones spent with lovers and family, and ones alone. She thinks about the old, old story (“no room at the inn”) and other exiled, lonely people. On the eleventh, she goes night-walking, marvelling at the snow’s “constellations” and the glistening, lit-up windows; she is already regretting the passing of the shortest day. Finally, on the twelfth, she shows her true love how much she has learned, giving her a present of logs and matches. Together they set a fire that throws “companionable shadows,” and sing to one another of the partridge and the pear tree.

As Irving and Dickens showed in their early attempts to resurrect the spirit of Christmas, and as Smith sees so clearly today, there is real, assayable value in the old traditions and great enjoyment to be had from them. Even in our prickly individualism, hemmed in by consumer goods, there are moments when we can escape from safe, homogenized lives to experience the tingling pleasures of heat and cold, of icy days and starry nights. The Christmas story reveals these freely available good things in front of us as it binds us to custom and continuity, drawing us back. Amid plenty and diversity it acts cohesively, bathing us in Platonic firelight and seating us at an imaginary hearth with ancestors for whom storytelling “in the light and the dark” was the greatest delight.