essays

Electric Literature’s Best Novels of 2015

Each year, Electric Literature polls our staff and regular contributors to pick our favorite books of the year. For fairness sake, books by Electric Literature staff were disqualified (although we encourage you to check out Michael Seidlinger’s novel The Strangest and Lincoln Michel’s story collection Upright Beasts.) Otherwise, there were no restrictions, and the resulting list of nominated books was long and eclectic. We then collected the books that received the most nominations to make our final lists. You can also read our list of the Best Short Story Collections of 2015 and Best Nonfiction Books of 2015.

Below, in no particular order, are our favorite novels of 2015. The resulting 21 books include literary luminaries such as Kazuo Ishiguro and Michel Houellebecq alongside exciting debuts by the likes of Alexandra Kleeman and Sarah Gerard. These are stories of tooth auctioneers, figure skaters, talking crack cocaine, dragons, and much much more. Put them in your to-read pile if they aren’t already.

You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine by Alexandra Kleeman

Alex Kleeman, in her magnificently realized You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine, [contemplates] the yoke between individual body and singular self. As this story from the book reflects, not only are her characters shorn of even their names — they are, simply, A and C — but the world’s larger population has begun fleeing the demands of stress, and chores, and even love itself. And yet, she reminds us, even under such ascetic conditions, some things are irreducible… and perhaps the most irreducible fact of all, our physical selves, has become the foundation of an alimentary-industrial complex that feeds upon us daily.

Alex Kleeman’s work will likely stir the “gift-curse of recognition” (her typically tart phrase) within you. Happily, though, it should also have you laughing through the existential horror.

– Cal Morgan, former Executive Editor, Harper, introducing “Disappearing Dad Disorder,” excerpted from You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading no. 170

You can also read our review of You Too Can Have a Body of Mine and our interview with Kleeman.

Delicious Foods by James Hannaham

Delicious Foods…begins in a swampy hell. Our hero, Eddie, who has no hands, struggles to drive a stolen car to a sweeter place off interstate 45, where his aunt lives, in order to escape a horrible series of events that are not revealed until the end of the story. Darlene, Eddie’s mother, is grief stricken by the sudden death of her black activist husband; her identity becomes entirely eclipsed by crack cocaine. Darlene is literally held captive and drugged by a sinister food chain, human trafficking operation. Although the book is primarily focused on desperate acts born out of grief, drug addiction and rough terrain, “Delicious Foods” is, on a larger scale, an ambitious story about systemic racism and self-destruction — traps that can lead us to our own demise.

– Antonia Crane from a list of books about addiction and recovery

You can also read our interview with James Hannaham.

The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro

In The Buried Giant, an elderly couple sets off on a journey through a mythical England populated by ogres, dragons, knights and giants. Axl and Beatrice are in search of their son, whom they can’t quite remember how they lost. This is because the inhabitants of The Buried Giant’s mythical world suffer a collective amnesia, a ‘mist’ that keeps them from holding onto certain memories, both personal and historical. As we travel with Axl and Beatrice, the novel asks us what memory (and forgetting) means to a person, to a couple, to a society. In many ways, the book is surprising (The New York Times calls it ‘a departure’), but it also showcases some of Ishiguro’s most essential qualities as a writer: subtle prose, a dreamlike atmosphere, and powerful questions about loss and memory.

– Elysha Chang in her introduction to our interview with Ishiguro

The Book of Aron by Jim Shepard

Like Schindler’s List, The Book of Aron is haunted by a great man, in this case, Janusz Korczak, the pediatrician famous throughout Europe and appointed caretaker for a set of Jewish orphans. Central to the lives of saints, the act of bearing witness — to Korczak, to the struggles of friends and family — is performed by a boy who is not a model of moral purity, even as the occupiers’ crimes dwarf his own. Wracked by guilt, Aron needs to believe in Korczak. And Korczak knows it.

Shepard’s no sap, and his hunger for certified historic fact is voluminous, practically what underlies his entire literary career. As in another of his most impressive works-to-date, a short story titled “The Netherlands Lives with Water” set in Holland of a not-so-distant-future, inundated by relentlessly climbing ocean levels, the characters in The Book of Aronfind themselves practicing “a sort of apocalyptic utilitarianism: on the one hand they were sure everything was going to hell in a handbasket, while on the other they continued to operate as if things could be turned around with a few practical measures.”

– J.T. Price in our review of The Book of Aaron

The Story of My Teeth by Valeria Luiselli

There is something astonishing that the Mexican novelist Valeria Luiselli has achieved across the space of her three books — Faces in the Crowd, Sidewalks, and her latest The Story of My Teeth — by writing into and out of relingos, the forgotten, inexplicable open spaces of Mexico City…Luiselli has a talent for satire. She puts us in the room with a pile of old teeth — as Siddhartha has put Highway’s old teeth in the Jumex Juice Factory Art Museum — and shows us how far people will go, how a story is the only thing that gives objects value. A book without a story is worthless paper, we know deep down. The pleasure of reading, and living, exists in traversing the passages of the labyrinth and not in discerning the route to its center.

– Geoff Bendeck in our review of The Story of My Teeth

You can also read our interview with Valeria Luiselli.

The Small Backs of Children by Lidia Yuknavitch

The Small Backs of Children requires the reader to let go and give into the prose and story. Why do the writer’s friends so determinedly latch onto the idea of saving the young girl and bringing her to the writer? Once I had finished the book, I knew I had read something brilliant…The Small Backs of Children is ultimately an examination of the spectrum of creation — whether of self or art — and how often creation can uneasily exist along with destruction.

– Sarah Galo from our review of The Small Backs of Children

The First Bad Man by Miranda July

This novel will be talked about for its ability to test boundaries, particularly the boundaries of sexual labels or forbidden love. But it’s worth mentioning the readability of July’s prose. Her success in carrying us through the strange world of Cheryl Glickman is a testament to her skill. This is a bizarre story, but an alluring one, and one that ends in a moment of satisfaction. July creates a character in Cheryl who elicits our empathy, but also a visceral response. Her conviction in her specific belief system makes her a character we want to understand, if not become. She understands herself, and she is most certain of the genesis of Kubelko Bondy. “I didn’t make him,” she acknowledges, “but I did each thing right so he would be made.”

– Heather Scott Partington from our review of The First Bad Man

Submission by Michel Houellebecq

Some have called Submission satire, others a dystopia. Is it a warning cry, a near-reality to be feared, or a conception of the darkest fears of the ignorant? The truth lies somewhere in between. Houellebecq himself — interviewed extensively following the novel’s now-infamous publication on the date of the Charlie Hebdo massacre — said in a September interview with The Guardian, “The role of a novel is to entertain readers, and fear is one of the most entertaining things there is.” Houellebecq’s work is emblematic — a re-spinning of — the fear-driven headlines that sell magazines and newspapers and keep TVs tuned to 24-hour news commentary. By distilling the traditionally hysterical language of news into the very plausible and mundane life of his narrator, Houellebecq forces his readers — of every ilk — to consider the effect of the stories we tell ourselves daily in 2015. Fear is a powerful seductress, and Houellebecq, with his description of a disconnected, academic life, understands that the most powerful way to explore something is to put it into the context of the ordinary.

– Heather Scott Partington from our review of Submission

Paulina and Fran by Rachel B. Glaser

It is a fiercely intelligent work of fiction — often hysterically funny, often painstakingly reminiscent of my own college years — and, while reading, one knows oneself to be in the hands of an extremely gifted writer. I eagerly anticipate whatever Rachel B Glaser does next, and I know that when Paulina & Fran finds its audience, I will not be even remotely alone in that.

– Vincent Scarpa from his introduction to our interview with Rachel B. Glaser

Binary Star by Sarah Gerard

Sarah Gerard’s new novel Binary Star is an intense story about a young astronomy student struggling with anorexia and her relationship with a long-distance, alcoholic boyfriend. Together, the destructive couple takes a road trip around the United States and experiments with veganarchism. As she starves and purges, he consumes. The prose reflects the characters’ behavior. Sparse and lean, Gerard’s writing hurtles forward with a momentum that seems bent on burning up, much like the stars her protagonist studies. It’s a novel that takes risks, both in style and subject matter. Women are told that writing about eating disorders is cliché, or that if they write about their bodies or their own narcissism they won’t be taken seriously. Sarah Gerard refuses to let those experiences be devalued and instead puts them at the center of a serious literary work.

– Kristen Felicetti from her introduction to our interview with Sarah Gerard

The Hopeful by Tracy O’Neill

Tracy O’Neill’s The Hopeful, set in the mind-warping world of competitive figure skating, ranks among the best, most transcendent sports novels in recent memory. Alivopro Doyle is a “hopeful,” one of thousands of girls skating endless hours at her local rink and dreaming of the Olympics. A fall breaks two vertebrae and launches her into a course of therapy, chemicals, and regret over one elusive jump, the triple Salchow. The book revels in physical elegance (skating as “flying without wings, contorting through the cold”), but its finest moments examine not achievement, but aspiration and disappointment: the moment before the jump, the ice after the fall, the stale locker rooms, the hospital beds. The novel, O’Neill’s first, earned her recognition as one of the National Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35 for 2015.

– Dwyer Murphy, Interviews Editor, electricliterature.com

The Sellout by Paul Beatty

Beatty’s fourth novel is another biting satire on race in America. Kiese Laymon in the Los Angeles Times called it “among the most important and difficult American novels written in the 21st century . . . It is a bruising novel that readers will likely never forget.” In the Wall Street Journal, Sam Sacks described it as “Swiftian satire of the highest order . . . Giddy, scathing and dazzling.” We call it one of the best novels of the year.

The Beautiful Bureaucrat by Helen Phillips

I told Helen Phillips that her novel, The Beautiful Bureaucrat, is an “existential thriller.” That might sound like an oxymoron: after all, existential literature is known for its lack of action. Existential texts are usually about being stuck: waiting for Godot, or trying to escape an insect’s body. The Beautiful Bureaucrat demands that you keep turning its pages to find out what happens. And yet Phillips’s book — absurd, uncanny, tinged with dread — owes more to Beckett and Kafka than to Lee Child or Stephen King. […] The Beautiful Bureaucrat is as much about the mysteries of marriage as those of human existence. Phillips has created an abstract world, but the see-saw of Josephine and Joseph’s relationship is realistic. Their essential connection gives meaning to the absurd landscape.

– Elliott Holt, Author of You Are One of Them, introducing “The Apartments of Strangers,” excerpted from The Beautiful Bureaucrat in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading no. 169

You can also read our interview with Helen Phillips.

Infinite Home by Kathleen Alcott

Grief is a difficult home to leave, everything outside it seeming foreign and incomprehensible. Though it’s musky and poorly lit, at least this home is familiar, protected. At least it’s yours.

Most of the characters in Kathleen Alcott’s richly layered second novel, Infinite Home, are pacing the dusty corners of loss and estrangement, but they also share a literal roof, the brownstone where they all rent apartments from Edith, their elderly landlady who is descending into dementia. Edith’s tenants — Edward, a burned-out comedian, Thomas, an artist mournfully recovering from a stroke, Paulie, a young man with a rare neurodevelopmental syndrome, and Adeleine, a woman nostalgic for an era in which she never lived — slowly creep out of their private stagnations and into each other’s lives in surprising ways.

– Catherine Lacey, author of Nobody is Ever Missing, introducing an excerpt from Infinite Home in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading no. 166

You can also read our interview with Kathleen Alcott.

Girl at War by Sara Nović

Sara Nović has an agenda. The violent conflicts in Croatia, where she has many friends and family, and the complicated history of that region have been obsessions of Sara’s for many years. Her powerful debut novel Girl at War (Random House, 2015) tells the story of Ana, a 10-year-old girl who is living in Zagreb when war breaks out in the early 1990s. In telling Ana’s story, Sara hopes to shed light on a time and a place about which many people still know very little.

Sara’s novel gives us familiar childhood settings of school and play and family life, as well as harrowing scenes of civilian war and make shift armies, of teenagers-turned-soldiers in abandoned buildings called “safe houses,” where the inhabitants are playing cards one minute and shooting their enemies the next. We travel through this world with Ana, at an age where she is just starting to make sense of the world around her, while the world keeps refusing to make sense.

– Catherine LaSota from our interview with Sara Nović

Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff

Cradle-to-grave novels require the kind of ambitious, ambiguous specificity Groff wields. Rather than describing every year of her characters’ lives, an ensemble of scenes, moments and memories are utilized to great effect. In the first half of the book, Fates, we follow Lancelot — ironically called “Lotto” — through a thicket of traumas and life-defining moments, starting with his birth during the eye of a hurricane in Florida. A boisterous college party introduces us to Mathilde, a lanky girl whose beauty relies on a magnetic oddness. She lurks in the background during this first part, though we can sense the galaxy of her love slowly colliding with Lotto’s, all through his aspiring and failed dreams of becoming an actor, and then his victorious triumph as a New York City playwright. […]

What rescues Fates and Furies are Groff’s sentences, as always lithe and poetic, unrolling like a glimmering carpet to the gray and uncertain territory of her characters’ inner conflicts. She wields an almost-wizardly command of language, specifically metaphor. Each page contains sumptuous pieces of imagery. “A tiger of light” prowls in a bedroom in the morning. Tree branches are “stunned as soldiers after an ambush.” Mathilde’s blood is “humming like a beehive.”

– Zack Hatfield from our review of Fates and Furies

You can also read our interview with Lauren Groff.

Beatlebone by Kevin Barry

Beatlebone tracks an imagined excursion taken by John Lennon in 1978 to Dorinish, his uber-remote private island off the Mayo coast. With the help of a philosophical local fixer named Cornelius, John evades the British tabloid press; falls down a psychological rabbit hole with a sinister communal trio of Primal Screamers inside an abandoned hotel; and considers his relationship with his wife and parents, his music and memory. All of this while trying desperately to make it to a gnarled, inhospitable piece of rock in the stormy Atlantic, where he can finally be alone with his thoughts.

– Dwyer Murphy from the intro to our interview with Kevin Barry

All This Life by Joshua Mohr

The news delivered in Joshua Mohr’s novel All This Life is captured by the second headline. Mohr’s bleak view of our wired present is clear from the opening scene, where we find the “Bluetooth chain gang” enduring rush hour traffic on the Golden Gate Bridge. The chain gang universally hates their jobs, and they long, Mohr tells us, for “a day to feel free. To be alive.” Why these emotions are any different than those felt by every commuter, in every age, is never explained, but what is explained is the reason for the unusually awful traffic: a brass band that has been marching across the bridge begins, one by to one, to jump into the bay, instruments and all. Paul and his teenaged son, Jake, are two of the commuters that witness the mass suicide, and Mohr describes Jake’s reaction with the following emoji: “a head with a can opener spinning around its crown and peeling up the skull and plucking out the brain and whirling it around on an index finger like a basketball.” Jake captures the entire scene on his phone, and then, like any modern teenager, he immediately uploads the video to YouTube. […]

The novel’s strength is that it dramatizes the implications of our online selves; Sara at one point refers to her video as her “digital, conjoined twin,” and this twin is definitely the evil sort, the kind that stalks you and makes your life miserable. We all have these digital twins, with varying degrees of evil depending on your browser history, and if you allow your mind to concoct worst case scenarios, we might all jump off a nearby bridge.

– Eric Howell from our review of All This Life

You can also read our interview with Joshua Mohr.

After Birth by Elisa Albert

After Birth roars with the anger of betrayal. Albert is abrasive and sharp, intelligent and painfully real. There is no room for gentleness in her novel, no time to waste looking for a kinder way of speaking. It’s as if After Birth, while raging against the isolation of motherhood, wants to reverse it. […] After Birth comes twenty years too late to truly be Riot Grrrl literature, but something about it begs that you put on the new Sleater-Kinney, notch up the volume, and breastfeed (in public, why not) while you’re at it. Because After Birth is looking for a fight, it’s unladylike, it’s pissed off, and it’s going to tear everything you thought about birth and motherhood to shreds.

– Jeva Lange from our review of After Birth

You can also read our interview with Elisa Albert.

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara is an unsparing novel that follows the lives of four college friends as they achieve the successes they once dreamed of and strived for. There is a fairy tale quality to the wealth and fame these men achieve, but like all fairy tales there is an underlying darkness. The darkness at the center of this novel emanates from Jude St. Francis, a successful lawyer by any measure, but a man who remains an enigma to friends and family nearly to the end. The reader bears witness to the aftermath of the childhood abuse Jude St. Francis suffered, and barely survived, with the understanding that the brutality of the witnessing cannot compare to the experience itself. Unable to heal himself, or be healed by others, Jude is a character that calls into question the redemptive narrative arc we too often expect from stories of trauma. Yanagihara would argue that this isn’t a story about trauma but about life. Either way, she asks the tough questions: how do we live, and why?

– Adalena Kavanagh from our interview with Hanya Yanagihara

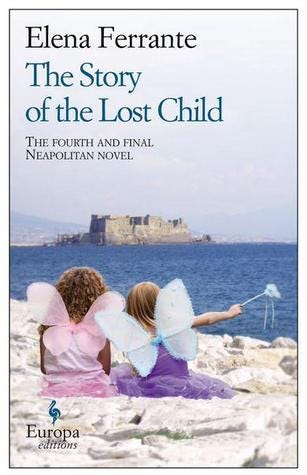

The Story of A Lost Child by Elena Ferrante

The subtitle of The Story of the Lost Child, “The fourth and final Neapolitan Novel,” broadcasts to Ferrante devotees and momentous and bittersweet occasion: the conclusion of the emotional, intellectually stimulating, and, at times, soap-operatic saga of Lila and Lenù, and their lifelong friendship that begins and ends in a working-class neighborhood in Naples. The Neapolitan novels are habitually referred to as a story of female friendship, however that description, especially in light of this stunning fourth novel, has always felt reductive. They are less the story of female friendship that the story of female identity, particularly female intellectual identity, and how relationships — platonic, romantic, and maternal — threaten, challenge and shape that identity.

Readers are highly recommended to enjoy these books sequentially, beginning with My Brilliant Friend, but for those who can’t wait to dive into The Story of the Lost Child may refer to our study guide, “Previously on the Neapolitan Novels.”

– Halimah Marcus, Editorial Director, Electric Literature