interviews

Uncertainty: A Conversation About War And Memory

by Maurice Emerson Decaul

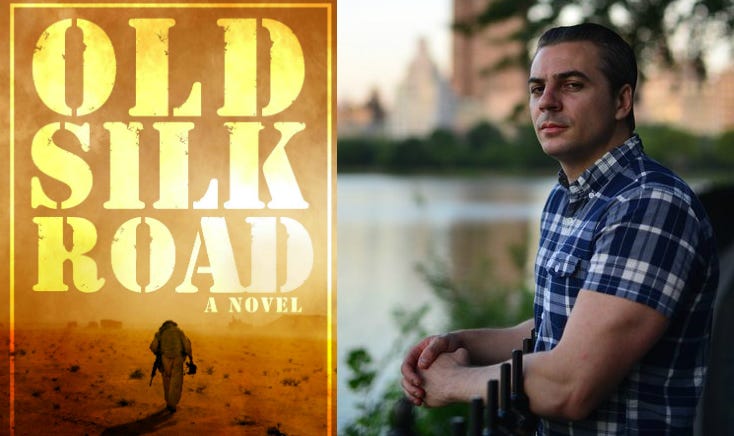

I walked into Swallow Café off the Morgan L a week before the massacre in Paris to meet up with Brandon Caro. We were to talk about Old Silk Road, his debut novel, recently published by Post Hill Press, but as fate would have it, Swallow Café because of the din and lack of available seating proved to be an unideal place. So, instead we decided to take a drive through the neighborhood and ended up for the most part talking about our wars and our experiences growing up in New York City a time before it was cool to say, let’s meet in Bushwick for anything, much less coffee.

My intent was to discuss the way Caro has situated the current American military involvement in Afghanistan, collapsing time through the juxtaposition of historical figures: Alexander the Great, The Khan, Dr. Brydon of the British East India Company, a unit of Soviet tanks and Pat Tillman, who is omnipresent in a dream time news cycle like, way. But as is common when veterans get together, we started to share stories, the type of discourse rarely discussed openly.

The President recently addressed the nation to describe the current way in which the use of the tactic of terror has evolved from the sophisticated mass casualty attacks of September 11th 2001, perpetrated by Al Qaeda, to a new, equally nefarious but exponentially more difficult to counter, low-intensity chronic threat posed by actors such as Da’esh aka ISIL ,whose modus operandi in Europe, North America, parts of North Africa and in Australia depends on individuals willing to commit murderous acts with little institutional support. The “Lone wolf” the “self-radicalized” person, he or she is called.

The drumbeats of this new war are being beaten. And with the deployment to Syria of American Special Forces, the rhetoric professing that there would be no American “boots on the ground” has been discredited. I bring this up to contextualize my conversation with Caro because we have both had our boots “on the ground” so to speak, me in Iraq and Caro in Afghanistan. As our elected officials’ debate strategy, our service people know already what might be asked, but it is important in our democracy for the demos not to be excluded. It is important for the demos to know.

Brandon Caro: I just want to talk about, the positive changes in New York in the last, I guess, twenty years, as far as the reduction in violent crime. I grew up here. I grew up in Manhattan. I was ten when we moved to Greenwich in 1992. And I just… I just remember an atmosphere of fear.

I just remember growing up during the crack and haze epidemics, fear really controlled my life to a large degree. I was a small kid. I couldn’t go anywhere alone. When we moved to Greenwich everything was different. We could go wherever we wanted. But we were talking earlier about how it’s not like that in New York anymore. It’s just not….It’s not nearly as dangerous as it used to be.

Maurice Emerson Decaul: New York is a very different city. I left New York in ’98, when I joined the Marine Corps.

BC: Yeah. Yeah, I think it was like… It was still a bit dangerous in the ’80s and then it’s got a lot less dangerous since the ‘90s.

I actually…I witnessed a murder in like ’99, or 2000, uptown, like 109th street. I was…like right in the place where it happened. It was in like a Chinese restaurant. I walked outside and a guy came in and shot a guy that was right behind us. I had never seen anything like that. But Iraq was a really dangerous place, certainly when you were there.

MD: When were you in Iraq?

BC: I was never in Iraq. I just know from the news and the people I know.

MD: Yeah.

BC: But it was a really dangerous place. Basically, ’03 to ’07 and then it wasn’t, you know?

MD: Yeah. Yeah

BC: Really, it was Pre-ISIS Iraq, after the Sunni Awakening it experienced a–

MD: –A surge in violence.

BC: –Right. It experienced first a surge in violence and then a drop in violence and now it’s obviously more violent, I think, than it’s been.

MD: I was speaking to someone who was telling me about his family. one of his brothers is a General in the Iraqi Army. His brother was talking about Tikrit and using American bombs on ISIS because they can call them in. Another of his brothers, I’m sorry, his cousin had just been shot by an ISIS sniper.

BC: Really?

MD: Armpit, yeah.

BC: Axillary, yeah.

MD: He didn’t die. He’s lucky.

BC: He didn’t? That’s interesting, because…a guy I served with was shot under the arm pit by a sniper and he was killed. He was on the MK19 and it jammed because that’s what they do.

MD: I hate the MK19.

BC: He was trying to fix the tray and he got shot underneath the arm pit.

MD: Our last or second to last night in Iraq we were coming back from patrol close to our compound, we heard guns fired. Nothing major. It was a wedding.

BC: A celebration

MD: But someone took the opportunity to take a couple of shots at our vehicle.

BC: Yeah.

MD: And, you know, timing–

BC: And pre-armor, right?

MD: Yeah. This is 2003. This is July 2003.

BC: You didn’t have doors.

MD: We didn’t have doors.

BC: Dangling your feet outside the doors.

MD: Yeah.

BC: That’s crazy.

MD: So someone took the opportunity to take a shot at the vehicle. And timing played a part in not getting shot in the same area.

BC: You were in a–

MD: I was in a Humvee. I was the A driver.

BC: But the doors was open.

MD: The door was open.

BC: That’s fucking nuts.

BC: One of the only times I was ever shot at was on base. The bases were really not well defended.

MD: This was in Afghanistan?

BC: Yeah, in Afghanistan. We were under this big tent and someone fired a RPG and it just barely missed the tent.

MD: That sucks.

BC: Yeah. Well it was great. But if it had hit the tent, it would have been a mass casualty because there were at least one hundred people in the tent, everyone was on the Afghan side of the base, it was like a dinner, you know? It was like an event, you know? A guy, someone fired an RPG. It missed, then they just started with machine guns…and then we got our stuff, and went back to the front and it was already over.

MD: That’s how it happens. It happens very quickly.

BC: Yeah, it didn’t last very long. It felt like a long time [laughs]

MD: It does. It feels like a long time in the moment, but in retrospect, you know, those engagements–they happen…[snaps fingers]

BC: Yeah. Really, really fast.

MD: With us, there were a few occasions sort of like that. Not with RPGs, no one had a chance to shoot those at us because the Marines were on their game, man. On their game. We were in control of the Nasiriyah Museum, which is on the banks of the Euphrates. One night, maybe 2o’clock in the morning all hell broke loose. I mean literally every piece of ordnance we had started going off. And I woke up.

BC: Oh! I think I heard about this.

MD: Did you heard about this? You heard about this? [Laughs]

BC: Yeah, yeah. I think I heard about it.

MD: You know what a CLU is?

BC: No, what’s a CLU?

MD: The CLU is the aiming system for the Javelins.

BC: Oh, yeah. I do.

MD: The great thing about the CLU is that it allows you to see in Infrared. Not only in night vision, so also body heat. One of the Marines was scanning the water and saw a small group, maybe three people, stepping out of the Euphrates and moving towards the building and he engaged them with the SAW and I think that was it, I think it was over with his engagement. One of the Iraqis had an RPG so he engaged them and everyone else engaged too. So we were sent out the next morning to recover

BC: Whatever was out there?

MD: There was nothing out there.

BC: Oh, really?

MD: Yeah. I mean, we soured.

BC: They just took off or something?

MD: I don’t know. I have no idea if we hit them or did not hit them. I don’t know. I mean who knows?

BC: You bring up uncertainty, which is something that I experienced that would influence my book, Old Silk Road.

There was a really nasty IED that went off outside the FOB, the casualties came into us… to be treated and evac’d out, so we did that. There was one KIA….three or four wounded.

MD: Americans?

BC: All Americans, and this one…one woman, too, actually. We treated them and then evac’d them and then like an hour later they brought in this little kid. He must’ve been, like fourteen. He had these little whiskers on his moustache and they were like, “Doc, look at him. Check him out. Make sure that he doesn’t have any injuries, because we’re going to interrogate him and we don’t want him to say that we beat him up.” I was looking at him and they were like, “You can’t interrogate him” but obviously I wanted to fucking ask him questions you know? So, I think I asked one of the ANA soldiers “is this the one?” And he said “We’re going to find out and if he is, we’ll cut his head off.” The kid-his face just like…I mean, I had never seen such fear in my life.

MD: I can imagine.

BC: Because they will, they will do whatever they want. And we had absolutely no control. So I checked him out, he didn’t have any injuries, I think, I actually took some photos, too, but that was it. And then I never…I never heard from him, I never saw him again. I don’t know what happened. I don’t know if he set off the IED or not. He just…he just, like, Disappeared, completely.

And I use that in my book.