Interviews

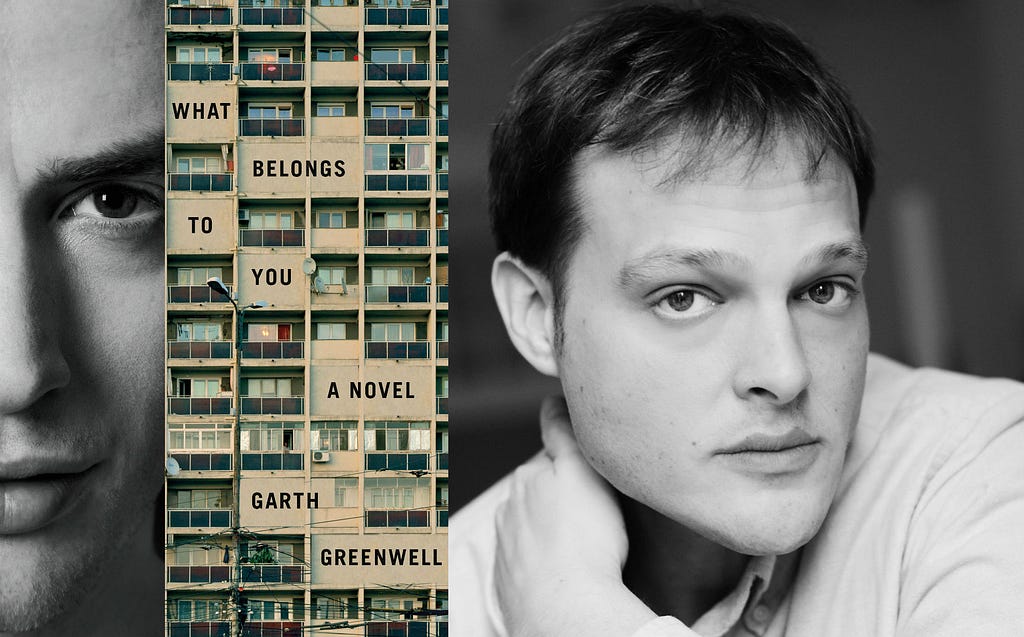

A Syntax Of Doubt: An Interview With Garth Greenwell, Author Of What Belongs to You

by Laura Preston

Garth Greenwell’s debut novel, What Belongs to You (FSG, 2016), opens underground, in the public toilets of Sofia’s National Palace of Culture. There, an American high school teacher encounters Mitko, a young prostitute with broken teeth and a curious, sphinxlike appeal. What follows is an exhaustive trip through the narrator’s consciousness as he recounts, in confessional, first-person mode, his infatuation with Mitko from its inception to its end. Mitko is at once a swindler, a lover, an object of lust, a tour guide through a certain kind of underworld, a riddle with no answer, and a grubby porthole through which the narrator can examine, dimly, his own childhood in the foothills of Kentucky.

Like a Tibetan throat singer, Greenwell performs the uncanny feat of sustaining two notes in one breath. Frank depictions of sex, of venereal disease, and of rotting infrastructure lend his prose a certain stench, and keep us grounded in a post-Soviet landscape with all of its earthiness and grit. But Greenwell’s tone retains a measure of delicacy: his sentences are formal and refined, often carrying the narrative into the celestial. From one angle the book looks like a long act of solipsism, yet from the other side the book is outward-looking, even journalistic. Greenwell documents the texture of contemporary life in Bulgaria with care, and the American reader will exit the novel familiar with the country’s language and its customs. And while the book is on the one hand a work of interiority, it’s also a detailed study, down to the movement, the manner, and the dirt under the fingernails, of Mitko, who seduces us as slickly as he does the narrator, and who still, somehow, remains an enigma.

“I used to be an opera singer,” Greenwell said on a recent Friday afternoon over coffee on the West Side. After leaving conservatory, he pursued an MFA in poetry at Washington University in St. Louis, then a PhD in English literature at Harvard. He left academia to teach high school in Bulgaria, and then returned for an MFA in fiction from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His look is pure flâneur — high cheekbones, wandering gaze — but he speaks with faintest of Kentucky lilts. We talked about St. Augustine, Apophatic theology, cruising as a poetic genre, and growing up gay in the nineteen-nineties. He apologized for being a little out of it, as the previous night, lost in a particularly good reverie, he had missed his stop on the subway and had to retrace his steps. “God,” he said, “I suddenly came to and was on the other side of the river.”

LP: For a long time your relationship with language was as a poet and an academic. What drew you to the novel as a medium?

GG: My time as a high school teacher in Bulgaria was really the beginning of the shift from poetry to fiction. My poems became more narrative, and then eventually I was writing poems that were scenes. I was in Bulgaria, and all of a sudden I started hearing sentences that were clearly not broken or blind, and I had no idea why that was or what I was doing. I had never taken a fiction workshop. I had never studied fiction, even as a scholar, but I just started hearing language in a different way. Somehow that was bound up with Bulgaria in a way that I don’t understand.

LP: How did you end up in Bulgaria in the first place?

GG: By accident. I was in a PhD program at Harvard but decided that I didn’t want the life of an academic, so I left to teach high school in Ann Arbor. At Harvard, the most important relationships in my life were with books, and the most urgent things in my life were my own thoughts. Then all of a sudden I was in Michigan, and I was intricately involved with the lives of seventy teenagers. I discovered capacities for feeling that I had not suspected before. As a teacher, your job is this kind of long looking; you watch your students in a way no one else does, and I got incredibly caught up in the narratives of my students’ lives. It was an extraordinary education in narrative.

While teaching in Ann Arbor, I was living in a horrible apartment complex right across the street from a retirement home. One day I woke up and thought “I’m going to blink and be moving across the street.” At the time, I had never really been abroad, so I went on the market to go abroad with the same agency that had placed me in Ann Arbor. I went on the market late, and there were two jobs left: one at a posh Swiss boarding school and one in Bulgaria. I knew one person in Sofia, a friend of mine from music school, and I just thought, “This is going to be the more interesting experience.”

The Bulgarian school serves really, really smart Bulgarian kids who come from all over the country. The school historically — and to some extent still — represents a way out of a place in which it is very hard to imagine a future for oneself.

Sofia ended up being a fascinating place. People say that about every country on the border of Europe and Asia, but I had never been anywhere where history as palimpsest was so evident. It’s an ancient city. If you stand on the street by the Serdika Metro Station, you can see an Ottoman-era mosque, an Orthodox church that dates to the Fourth Century AD, Soviet-era apartment complexes. Next to it you have a brand new metro station funded by the EU, and if you descend into the passageway, you can see Roman ruins.

LP: It’s a far cry your home state of Kentucky, yet in the novel, you still manage to render both places on the page, side by side. Did living in Sofia inflect your own understanding of Kentucky?

GG: I really did. Everything in Bulgaria was foreign to me, and I was living in a foreign language that I was really struggling to learn. But then I kept having these experiences where I would meet gay men cruising in parks, and the conversations I would have with them were the same conversations I had with the first gay men I met in Kentucky when I was sixteen years old. It was in the way these men imagined their lives — their horizon of possibility was drawn at the same place. I felt both surrounded by total foreignness, but I was also back in the world of my childhood where the kinds of interactions you can have as a gay man, with other gay men, were narrow.

The landscape of Bulgaria, too, is very similar to Kentucky. There are beautiful mountains and lots of farmland. It’s a society that in the last fifty years has quickly transformed from been largely agricultural to largely urban. Kentucky is like that too.

So in Bulgaria, I had this recurrent experience of being thrust back into the past I had fled. I think I had to go to Bulgaria in order to be able to think about Kentucky.

LP: I think this becomes most evident in the middle section of the book. One of the most interesting decisions in the novel, to me, is this section. At the novel’s open, we’re in Bulgaria in the present day. Then, about sixty pages in, you open up a wormhole in the narrative and step out into another universe in both time and space. What follows is a forty-page mammoth paragraph — no indentations, no line breaks — that carries us through recollections of a boyhood in Kentucky. We break from orthodox narrative rules and enter something closer to prose poetry. It’s a bold structural move. Could you talk a little bit about this rupture?

I really felt as though I was seized by a voice, and the voice was possessed of this rage that I found really frightening.

GG: Writing that middle section was absolutely terrifying. I really felt as though I was seized by a voice, and the voice was possessed of this rage that I found really frightening. So I just started writing and followed the voice as it moved between the very particular landscape of Bulgaria and fell back through these different levels of memory.

I wrote the first draft of the middle section very quickly, and I could only write it on trash. I wrote it on the backs of receipts and scraps of paper. I couldn’t write it in my notebook, and after I typed it up I couldn’t look at it. It made me feel physically nauseous. I put it away for a year and I didn’t look at it.

Then I started re-writing it. It went through far more revision than any other section, and as I distanced myself from the first part of the book I realized that there were things about the narrator I didn’t understand. He’s always confessing things, all of the time, but in another way he’s so guarded. He’s always keeping the reader out, and is, himself, distant from his own experiences. I soon realized that the middle section is meant to answer the question: “How did this guy get to be this way? What made him the kind of person who is so attached to language as a medium of expression and in another way, constantly hiding things from himself and from others?”

LP: I’m reminded of a line from Mitko that seems to contain the thesis of the novel. In a moment of anger, he turns to the narrator says something like, “The trouble with you is that you don’t know what you want. You say one thing and then another.” This brings me to a question of syntax. Your sentences build and swell — they are constantly self-revising, doubling back, and negating themselves. Each one is like a little a work of psychic origami. How did you develop this particular syntax, and in what way is it related to your poetry practice?

GG: I’m endlessly fascinated with the elastic capabilities of English. English — because it’s lost nearly all of its inflections — is a really limited language syntactically, compared to German, for example, and certainly compared to Latin. Yet despite those limitations, English syntax is so expressive and such an extraordinary vehicle for capturing the movement of consciousness. I do think that my sense of that comes from poetry, especially the 17th century metaphysical poets, who are the most important to me as a writer and a scholar. And it comes from the contemporary poets with whom I studied: Carl Phillips, who uses this syntax of doubt, this syntax of feeling your way forward, inch by inch; and Frank Bidart, who is a master of the sentence suspended over a long period. Then going further back, it also comes from Augustine’s Confessions, which I think is an extraordinary work of literature. What Augustine gives us in his Confessions is a portrait of a mind that says one thing and then says, “Oh no but what I really mean is. . .” and “Oh no, actually, that’s not right.” It’s Apophatic theology: a way of locating truth through triangulation.

Then the non-literary influence on my particular syntax is operatic singing, which is an athletic enterprise involving the entire body — you use your lungs to mold a phrase that moves through time incredibly slowly and that has a long arch in shape. I do feel language like this — as something physical. I have to feel the musculature of the sentence.

So I think all of those things conspired towards a certain of shape of sentence, a sentence whose music is the music of interrogation, and of doubt, and of self-questioning and self-revision. I’m only interested in assertion as something that can be worked against.

LP: It’s interesting that you bring up the 17th century, as so much of this novel, to me, read like a contemporary pastiche of 19th century novel. Many characters are names only by their first initial, and much of the narration comes in this high, rather formal register. I couldn’t help but think of Thomas Mann, of Henry James. Do you see this work as having some sort of inheritance from the 19th century — beyond all the usual inheritances, that is?

GG: It doesn’t feel exactly right to say that I align myself with the 19th century, but then it also feels not right to say I don’t. Because the syntax I use isn’t Dickens’s syntax. It’s not George Elliot’s syntax. It’s not Jane Austen’s syntax.

Thomas Mann, Henry James, Proust. . . all of these writers are queer writers, and it’s evident in the sense of transgression in their language.

Yet one thing that annoys me when people talk about the novel of consciousness — especially the 19th century novel of consciousness — is that it’s not acknowledged what a queer tradition that is. Thomas Mann, Henry James, Proust. . . all of these writers are queer writers, and it’s evident in the sense of transgression in their language. These authors maintain a kind of syntactical propriety that is at once excessive and extravagant, but also attached to a kind of grammatical decorum. In Proust, you have these sentences that just billow far beyond anything that should be possible and are totally transgressive in that way, but are also so attached to elegance and propriety. There’s something about that that to me is very queer.

And that’s the sort of character my narrator is. I mean, this is a guy who came to his understanding of his sexuality through anonymous sex in parks, which, you know, was part of the gay male experience for a long time. There’s a way in which the narrator longs for a kind of elegance and a kind of dignity. His experience of himself, not just because of his sexuality, but also because of his sexuality, is an experience of shame.

LP: He’s so ashamed. At some point he describes his sexuality as “That humiliating need that has always, in even in my moments of apparent pride, run alongside my life like a snapping dog.”

GG: Right. He feels is sexuality as a source of great humiliation and degradation, but also as a source of great exaltation. His sexuality is a door that opens him up to an experience of transcendence that he gets nowhere else. There’s a way in which I feel like those syntactical structures kind of improve that in the way that they’re both transgressive and break grammatical propriety. Some of my sentences are ungrammatical at times.

LP: I want to stay on the topic of language, but also shift gears a little bit. There’s a lot of active translation that happens between the Bulgarian characters and the English-speaking ones. Readers of the novel will encounter English approximations for Bulgarian words, English words with no Bulgarian equivalent, and moments where neither language is sufficient at all. There are also moments were you leave full sentences in Bulgarian intact on the page. Could you talk a little about the decision to place the Bulgarian language in the forefront of the novel?

GG: One of the things that I hope happens in this novel is that you see someone learning a language. If I’m going to represent the consciousness of someone going through that process, the other language had to be on the page. In some ways, it was just about verisimilitude: I wanted to get the sound of the place. But I also love that particular space of consciousness where everything is doubled because you’re thinking in two languages at once and engaging in a transaction between them.

LP: And so much of the book is transactional. There are exchanges of money, of sex, of affection — sometimes fair, and sometimes profoundly imbalanced.

GG: Right! And language is a big part of those transactions. We never experience anything in the world that is not mediated through language. That’s true, even, of something like sex, which seems to promise a kind of escape from the constant movement of consciousness, but it doesn’t.

In some way, the constant transactions between Bulgarian and English are a synecdoche for any kind of interaction between two people. You have these moments of contact, and in some ways those moments of contact are everything, and yet they’re also never certain, always imprecise, never fully accurate. So much of the other person is always lost. Translation is just a metaphor for any kind of interaction between people.

LP: Those moments of contact are rare, but when they happen they can shock you. I loved the moment, near the end of the novel, where the narrator is sitting in a crowded waiting room while an English-speaking nurse recites a list of STDs for which he will be tested. As other patients begin staring, the narrator realizes with some horror that the names of the STDs are exactly the same in Bulgarian as they are in English.

GG: Bless your heart for not asking if any of this is autobiographical.

LP: We’ve talked a bit about the interiority of the narrative, but there’s an aspect of this novel that’s also outward-looking. There is wonderful tension in this book between private and public spaces. As we plunge through private layers of consciousness, we’re also exposed to a rather journalistic account of Sofia, specifically the spaces inhabited by members of the gay community. What, to you, is private space? And what is public space?

GG: I was thinking about this recently: just as my early education in music was really an education in writing, so were, I think, the years that I spent cruising bathrooms and parks for sex. In every place I’ve lived I’ve found these spaces, often without any kind of indication that they were there. The book begins in one of those spaces, in the subterranean bathrooms beneath the National Palace of Culture in Sofia. It’s a real cruising space, and everyone in Sofia knows it. Straight people hardly go there because it’s so notorious.

What I’ve come to realize is that finding these spaces is an exercise in reading. The first time I went to those bathrooms in the National Palace of Culture, it was my second, maybe third week in country. I was exploring downtown with friends. We just needed to go to the bathroom, and we saw a sign for the toilet. There was no one around. There was nothing to see or sense. But as I started descending those stairs, I just knew. I turned to my friend, who was straight, and said, “Men are having sex in this bathroom.”

I was so new to Bulgaria. I barely spoke the language. I didn’t have any idea how to read social cues. I was constantly making mistakes. Then I entered into this space where I was absolutely fluent in the language. All of the codes of cruising were exactly the same. I knew exactly how to act. I could communicate complicated messages in this effortless way. It was a moment in which a random stimulus of experience snapped into a kind of focus and became legible. It felt like an exercise in finding significance in the same way that reading poetry is training in finding significance, finding symbols. I’m fascinated by poetry as public and private speech. Cruising also creates a private, lyric space of intimacy within a public space.

That transactional space between privacy and publicity is the space of poetry, the space of cruising, the space of sex.

I hope the book reproduces that experience of being in a public and private space at the same time, which is also, for me, what sex does. Sex is this experience where you are really focused on another person with a kind of intensity you seldom have. But it’s also, at least for me, an experience that thrusts you into the most intense kind of interiority. That transactional space between privacy and publicity is the space of poetry, the space of cruising, the space of sex.

LP: Which contemporary Bulgarian authors are you most excited about?

GG: There is not a lot of Bulgarian literature that’s been translated into English, but the landscape of Bulgarian literature has been radically transformed in the last ten years the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation, an organization that supports Bulgarian literature and fosters connections between Bulgarian writers and English language writers. They’ve developed a relationship with Open Letter Books, and most of the Bulgarian literature that’s available in English is available through that press.

There are some younger Bulgarian writers who are incredibly exciting. The one I would single out is Dimiter Kenarov, who is an extraordinary poet in Bulgarian, and an incredible journalist and essay writer in English. He’s written about the Bulgarian writer and dissident Georgi Markov, who’s famous because the Bulgarian KGB killed him with a poisoned umbrella. There’s also a writer named Theodora Dimova who has a book called Maikite which means The Mothers. The book is so fierce, and has these sentences that are so intense and possessed with emotion.

LP: And is there any tradition, at all, of queer literature in Bulgaria?

GG: There are only two openly gay writers I know who write in Bulgarian. One of them is a poet named Nikolai Atanassov who lives in the States and wrote the first sexually graphic gay literature in Bulgarian. He writes in Bulgarian and publishes in Bulgaria, but had to move to the United States before he could do that. The other one is a gorgeous writer named Nikolay Boykov.

I mentioned earlier that my experiences in Bulgaria constantly reminded me of my own coming of age as a gay person in Kentucky. But there was one major, important difference between those two experiences: for my Bulgarian students, I was the only openly gay teacher they had had, and for almost all of them I was the only openly gay person they had met in real life. That meant that a lot of students came to talk to me.

I could read these books, and even if it seemed in many of them the value of gay life was a tragic value, it was still valued.

What became clear to me was that the biggest difference between being a gay teen in Kentucky in the early 90s, and being a gay teen in Bulgaria now, is that even though everything around me in my daily life taught me the lesson that my life had no value, I could read James Baldwin and Edmund White. I could read these books, and even if it seemed in many of them the value of gay life was a tragic value, it was still valued. Those books showed me a representation of gay life that bestowed upon that life a full measure of human dignity. My Bulgarian students have none of that.

LP: Will your students be able to read your book someday? That is to say, will the book be translated into Bulgarian?

GG: It will be. And I’m almost certain that book will be one of the first books in Bulgarian to represent the lives of gay Bulgarians with dignity. And I know that if this book is noticed or discussed at all in Bulgaria, it will discussed as that, as a representation of gay life and as a sexually frank book. It’s going to be very hard to see this book as literature. That’s fine. In English, there’s nothing scandalous about this book. Nobody’s going to care that there’s gay sex in it. People are going to be able to think about it in other terms. In Bulgaria, I don’t think that will happen. I think people will just be like, “Oh, this is a book about gay sex!”

LP: And will you be going back to Bulgaria for a book tour?

GG: I hope to. The conversation, I think, is going to be about defending the place for this subject matter in literature. I’m happy to do that, because my life as a writer is largely in other places. I would like to do what I can to establish the most basic ground rules, which are that gay lives are human lives, dignified lives, and are just as deserving as a kind of reverent literary representation as any other lives and that, yes, graphic depictions of gay sex are absolutely literary and are absolutely consonant with a kind of language that I hope has an allegiance to poetic expression.

I am very happy to go in and make that argument as strongly as I can and take whatever heat there is because then I get to go home. As a writer, am very conscious of the extraordinary privilege and protection I have, as an American, to do that.