Craft

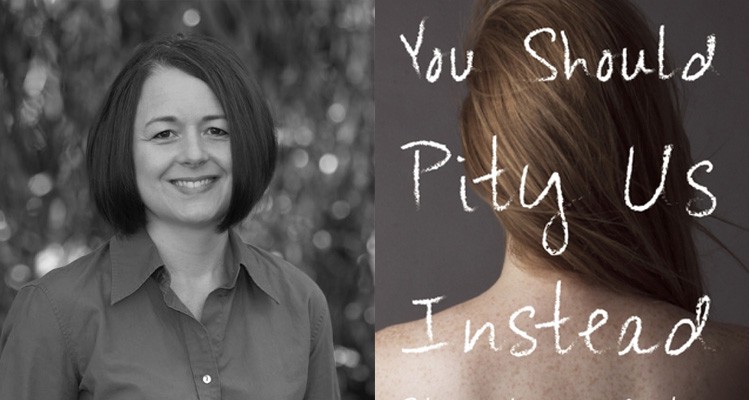

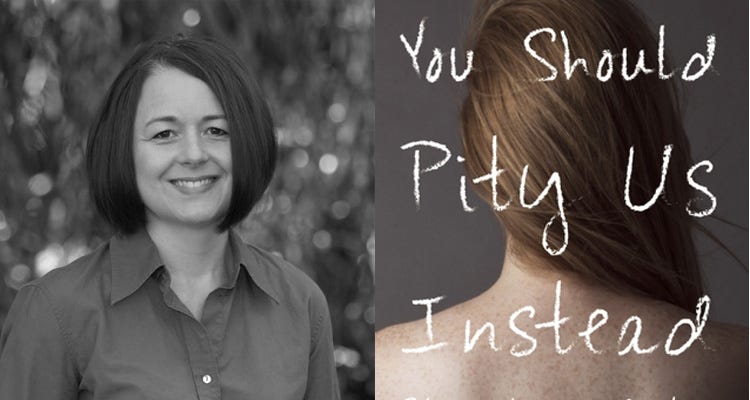

Truth is Shockingly Hard to Pin Down: An Interview with Amy Gustine

by Melissa Ragsdale

“When We’re Innocent” is featured in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading with an introduction from Kristen Miller. Amy Gustine’s new collection, You Should Pity Us Instead will be available from Sarabande Books on February 9.

Melissa Ragsdale: In this collection, we see everything from a mother searching for her son in the Gaza Strip to a woman who has fifty-five cats. Yet, even in the most remarkable of situations, the piece seems to hinge on the relationships between characters. When you’re crafting a story, how do you make these connections? What comes first — the situation or the characters?

Amy Gustine: What motivates and fascinates me is the spontaneous and unique meaning that arises out of the complex interaction between character and situation. The same person is capable of leading entirely different lives. Which life we lead is wholly luck — to whom we are born or adopted, whom we meet when, whether we get hit by a truck or win the election, and on ad infinitum. Equally, people in very similar situations will lead very different lives because of their personalities. So any story is equal parts situation and character — it’s THIS person in THIS situation that makes the story what it is. Character + situation = meaning. That said, I almost always start with situation, which is odd, because I have always considered myself a primarily character-driven writer; it’s the people who arouse our emotions in a story and I find all people fundamentally interesting. However, I love to do research, learn things about different jobs, time periods, academic disciplines, cultural forces, etc. My favorite type of story is both compelling on an emotional and psychological (i.e. character) level and set in a time and place that teaches me something new. One way to think about it is that the situation is the intellectual side of my writing and character is the emotional side. Characters show up in my work in some strange, instinctive way. It’s kind of like this: you decide where to go (the local post office, a ski resort, a dive bar, nineteenth century Warsaw) but you don’t determine whom you meet there.

MR: Right now our culture seems obsessed with ambiguous stories about violence/crime — I’m thinking specifically about the success of Serial, The Jinx: The Life and Death of Robert Durst, and Making a Murderer — and while this story has many of the same elements, it has a very different focus. This is not a story of “what happened?” (though, at points, it teases at the edge of it), but rather a story of “What now?” When you wrote this, did you have answers in mind about the reason and circumstance behind Jocelyn’s death? Or Brian’s alleged crime? Do you think those answers are important?

AG: No, I never tried to answer, even in my own mind, what precisely led to Jolly’s death or whether Brian had in fact raped the woman he invited to his apartment. Those questions are as unanswerable to me as they are to Obi and Brian. For me the story is about the longing for understanding and how often we are denied it — even about those things we ourselves do. Yet it is the ability to trust others, and to anticipate their behavior, that makes all social bonds possible, and social bonds are what make life possible among all the world’s animals. I feel like every culture is interested in stories about violence and crime because it’s part of our survival strategy to understand what others are capable of, what motivates them, what we need to be on guard against and how we can leverage other people to our own benefit. I think ambiguous stories about crime are a mark of an increasingly sophisticated society. High literacy rates, advances in science and a distribution of power across society (among people with different ethnic, religious, knowledge, and sexuality backgrounds) leads to opposing voices being heard, which leads to the idea that people in established positions of authority are not always correct and the appearance of things is not always a reflection of truth, and this quickly leads to the realization that truth is shockingly hard to pin down. That sometimes truth and being “correct” don’t even have meaning. It’s similar to the journey we make as individuals, from childhood, in which there is always a yes/no answer and the adults are always correct and powerful, to adulthood, in which there doesn’t seem to be a clear yes or no answer to anything.

MR: This story addresses two types of guilt: the outward guilt of whether or not an act was committed (e.g. guilty versus not guilty) and the inner feeling of guilt that both Brian and Obi are experiencing. For you, how do these inform each other?

AG: Mysteries novels have to end with a definitive and factually correct answer about outward guilt: who did what. You’ll notice, however, that a motive is always presented, because motive is the essential inner complement to the outer act that makes someone guilty. We are interested in knowing who did what, but in order to feel truly satisfied by a story we also need to know WHY they did what they did. This allows us to assign a DEGREE of guilt to people and that is a fundamental need of the human confronting another human. If you murder your husband because he was sexually abusing your daughter, you are less guilty than if you murder your husband because you want his life insurance — and I want to know HOW guilty you are. This will determine my level of fear of you — or my affection for you.

The law deemed Obi at fault (he ran the light) but didn’t feel it useful to punish him (because it was an accident not caused by obvious recklessness or misbehavior). From society’s point of view there was no deterrent or protective value to punishing Obi. But Obi himself wants to be punished. Without punishment, there is no expiation. Thus, decades later, his impulse is to interpret Jolly’s death as a kind of retribution. Outside an explicitly religious framework, we might call this magical thinking, and in some sense it is both a relief and a crushing blow to Obi, one more thing to feel guilty about. It reminds me of the ceremonies that some cultures have for making amends or being cleansed of one’s sins (Catholic confession or the cleansing ceremonies many communities have). The thing is that you have to truly believe in the power of those rituals or those authority figures to absolve you. For people who either don’t believe or don’t live in a culture that offers such rituals, the legal system is the route to absolution. For Obi the legal system failed even though it felt it was doing “the right thing.” For Brian, too, the legal system is not sufficient or useful. There is an irresolvable duality that hinges on the inner feelings he and the woman had: if at the time of their interaction he thought she was consenting, but she did not feel she had indicated consent, then he simultaneously did not rape her and he did rape her. Brian is simultaneously not guilty and guilty, and the law has no way of resolving that duality.

MR: Still thinking about guilt, this story centers around a lot of accidents and situations (e.g. Obi’s car wreck) that aren’t concretely the result of malice or intention. How does intention factor into innocence? Do you see any of these characters as being innocent?

AG: I don’t know if they are innocent. Maybe the woman is a liar who was hoping to get some money out of Brian by making a false accusation and she did in fact expect and want him to touch her as he did. Or maybe Brian knew or suspected his touches were not wanted or expected and now he’s rationalizing to make himself feel better. Maybe the traffic light had a momentary failure and Obi didn’t run a red. Or maybe his brain had a “short out.” Can we be blamed for a chemical or physiological process we can’t control? Looked at one way, his running the red light might be like a person who has a seizure and in the course of it knocks into another person who falls down a flight of stairs. The person having the seizure isn’t culpable, but they might feel guilty. However, parents who keep a loaded gun in their nightstand could be said to be culpable if their six-year-old kills herself even though they never intended the child’s death.

I have always been fascinated by the concept of guilt and how it relates to intention. It started in grade school. I was raised Catholic and went to Catholic schools run by nuns. I remember having a strong reaction to the notion of original sin even then. Taken literally, the Bible makes the claim that sin is inherited (original sin stains each of us because we are descended from Adam and Eve) while at the same time making the claim that we have completely free choice. I couldn’t resolve these two ideas into a coherent system of thought about guilt, responsibility, or punishment. Later I learned that some people think of the story of the apple in Eden as an allegory representing how humans are inherently capable of both good and bad, but this didn’t help. What if you do something that turns out bad but you had good intentions? We still feel guilty, and somehow being punished makes us feel better. But punishment doesn’t undo the damage. What if you’re faced with a Sophie’s choice? What if you did something without thinking or planning at all, a kind of “instinctive” badness? What about people’s urges? Serial killers feel very unhappy and restless until they kill someone. Does this in any way speak to their guilt? That their actions weren’t driven by greed, say, but by an urge that is linked to their ability to feel content? Maybe the rest of us shouldn’t feel so smug in our innocence, because we don’t have the urge to kill in the first place? Some people take great pleasure from helping others. Does this diminish the credit they should get for doing good? How does a belief in a reward (e.g. in the afterlife) impact how we should feel about a person’s good deeds? I’ve also thought a lot about what it means to believe that Jesus’ death absolved or saved us. His crucifixion is a kind of proxy cleansing ceremony: he suffered on our behalf. That doesn’t make sense to me. It seems to me like we would have to suffer ourselves in order to be cleansed. My work often struggles with all of these things: guilt, intention, responsibility, free choice. I never seem to get any closer to a coherent system of thought than I did in fifth grade. Which is probably why Brian and Obi never find out why (or if) Jolly killed herself intentionally.

MR: We have three incidents at play in this story: Jocelyn’s alleged suicide, Brian’s alleged rape, and Obi’s car wreck, none of which happen in real time. For you as the writer, how do these relate to each other? Particularly, how is Jocelyn’s suicide informed by the other two events?

AG: All three incidents are connected by the question of why. Why did Obi not see the red light? Why did Jocelyn commit suicide (IF she in fact did; intent is everything here). Why did Brian arrange for the woman to come to his apartment? Obi doesn’t know why he didn’t see the red light. Brian has a sense of why he invited the girl and he feels the urge to explain his motives to Obi — again we’re back to guilt being connected to motive, and to receiving absolution from another person who assesses our motive and, based on it, assigns us a degree of guilt. We can’t know Jolly’s motive, and neither can Obi or Brian, though they try because they believe if they can answer why, they will know whether or not they are to blame for her death. In the end, however, they must live without knowing. This is how it turns out most of the time in life: we must accept not knowing. But Brian gives Obi a gift: tell his wife that it is Brian’s fault Jolly died. This is a symbolic act, in which Brian takes on guilt he doesn’t truly bear which frees Karen (who presumably also feels guilty) and Obi and may expiate Brian’s actual guilt about the woman he (may have) violated. It also speaks to the way we are responsible for everyone. In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus says, “Rarely is suicide committed through reflection. If a friend addressed him indifferently that day, he is the guilty one.”

MR: Your characters throughout the collection are characterized by a unique three-dimensionality. Even seemingly minor characters (such as Adoo in “You Should Pity Us Instead”) come to us with full, intricate lives and backgrounds. What is your process for creating character?

AG: It’s organic to the story. In other words, I don’t decide ahead of time what type of person each character will be. I work off a kind of instinct that brings a person to me whole, the same way you might “get a vibe” off someone you meet at a party. Then as I lay down dialogue, facts about their past, actions, etc. I emotionally check each one against my instinct about this character. It either fits or it doesn’t. I think, as I said earlier, characters sort of come along with the situation and the concerns that that situation represents to me; they almost seem to pre-exist in the story. It’s odd, I grant. It’s like that old saying about sculpture — that the figure exists in the marble and the sculptor is unearthing it. It’s a mystery to me.

***

Amy Gustine’s fiction has appeared in numerous magazines, including The Kenyon Review, Black Warrior Review, North American Review, and others. Her story “Goldene Medene” received Special Mention in Pushcart Prize XXXII. She lives in Ohio