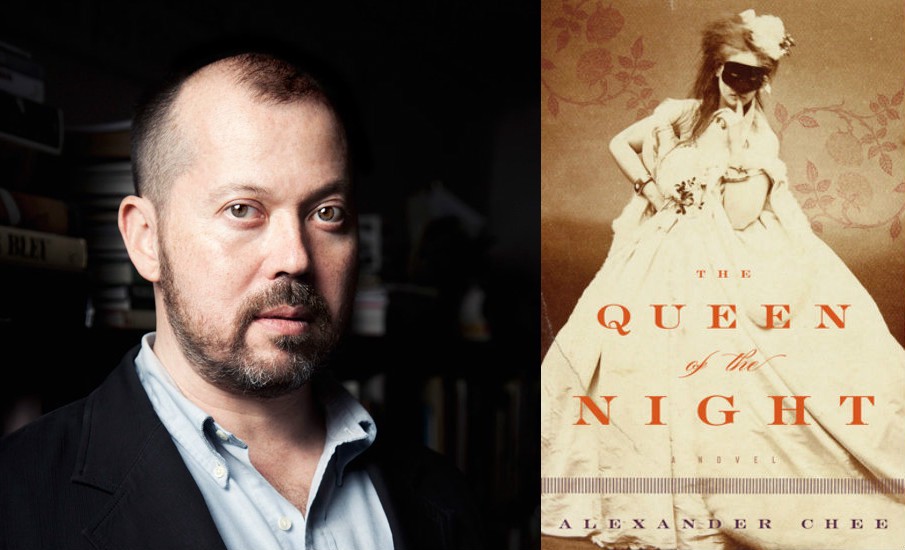

Interviews

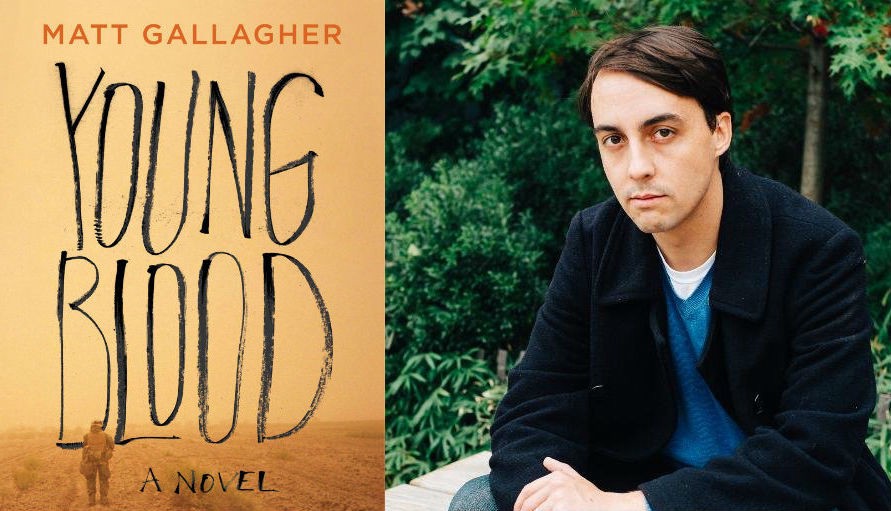

Matt Gallagher & Phil Klay Discuss the War in Iraq and Finding Purpose at Home

by Phil Klay

If you’d like to understand the modern American way of war, there aren’t many books that rise to the level of Matt Gallagher’s Youngblood (Atria Books, 2016). A war novel wrapped around a murder mystery and wedded to a Bildungsroman, the book dramatizes in ways no one else has the conflicting strategies that characterized the American effort in Iraq. Gallagher, an Army officer who served in Iraq, has long been a fixture on the veteran writing scene. He maintained a popular military blog while in Iraq, only to have it shut down by the U.S. military, and later wrote the memoir Kaboom, a smart and funny and irreverent look at his 16-month deployment.

In addition to writing fiction, he’s one of the smartest essayists and commentators on veteran’s issues, whether it’s on the members of my generation becoming ‘professional veterans,’ his meta-hot take on the hot takes on American Sniper, or what it’s like to compete in the world championship for the bar arcade game Big Buck Hunter (which, yes, counts as ‘veteran’s issues’). It’s fair to say many of us in the veteran writer community have been looking forward to his first novel for a long time, and Youngblood does not disappoint.

I sat down with him to discuss the novel, the various phases of the conflict in Iraq, and the modern American way of war.

Phil Klay: It seems like one of the challenges veterans have, when talking about the Iraq war, is of getting across the incredible complexities of a war that stretched across years.

The most vivid description of COIN I ever got as a young lieutenant was, “You know, like British imperial occupation.”

Matt Gallagher: The general public thinks of the Iraq war as one cohesive event, and the truth is there are so many parts of it, both from the American side and the Iraqi. There’s the invasion, of course, in 2003, which occurred over the course of three weeks and that was it. Mission accomplished. The Iraqis view that very differently. They call it “the collapse.” Their entire infrastructure, their entire way of life was totally upended. And then there are different phases: the sectarian war, the rise of the insurgency, from 2004–2006, then the shift to counterinsurgency, which took place in 2007. The most vivid description of COIN I ever got as a young lieutenant was, “You know, like British imperial occupation.” That’s not totally exact but it ain’t wrong, either. It’s about the long-game, being a jack of all trades immersed with the people, being beat cops and conducting electricity surveys and dealing with roadside bombs and snipers all at the same time. Obviously that conflicts with the popular American understanding of what war is, or at least what our wars “should” be. We push back fascist onslaughts! But the reality is that it’s much more likely that America will conduct another counterinsurgency campaign in the 21st century than we will fight another standard force-on-force war.

PK: Except that’s not really what we’re doing now. If counter-insurgency was the dominant philosophy of the second term of the Bush Administration, counter-terrorism has clearly been the dominant philosophy of the Obama Administration, with an emphasis on maintaining a light footprint, avoiding boots-on-the-ground, and a heavy reliance on drone strikes and kill/capture missions doing high value targeting.

MG: Counterinsurgency has an end-goal of a stable, self-sustaining local government. You can argue about its effectiveness, since the case studies that worked out pale in comparison to the case studies that didn’t. But at least it has a clear end-goal. The “counter-terror” approach, or whatever we’re doing now, doesn’t even have that as far as I can tell. It’s a low burn — but a constant low burn. It puts a heavy, heavy burden on special operations, and keeps the perpetual warfare machine going. It’s not about bringing the peace over there, or anywhere. It’s about keeping things calm back here. I can understand that approach, even appreciate it. But I find it deeply cynical and deeply disturbing, not so much as a veteran, but as a citizen of a republic.

PK: Your novel is set toward the end of our “boots-on-the-ground” phase in Iraq…the end of the era of counter-insurgency. And the different approaches to warfare that characterize different stages of the war come up in the novel, most clearly through the tension between Lieutenant Jack Porter and Sergeant Chambers. Jack is a young, untested platoon commander trying to do counter-insurgency, and Chambers is an experienced noncommissioned officer who learned how to be a soldier in a part of the war that was a lot more violent, and there’s a tug of war between these two for the soul of the platoon.

MG: I think the tension between Jack and Sgt Chambers is a natural one, in terms of their ranks and backgrounds — junior officer, just out of college, probably comes from a much more privileged background than most of his soldiers, and then there’s the battle hardened noncom who has been there and done that, walked the walk, who comes from a more blue collar background. Chambers is a product of his environment. He’s done what it takes to survive and bring his men home. There’s a Machiavellian aspect to Chambers that I found myself drawn to as I was writing him, and I hope readers find intriguing, as well. Say what you will about the man and his worldview, he gets things done. But his ‘war-is-war’ philosophy and approach comes with consequences, both physical and moral. And often enough, those physical and moral consequences are not the expected ones.

PK: And though Jack starts out wanting to get rid of him, once the tensions flare up in the town and there’s a lot more violence, Jack second-guesses himself because, brutal or not, too aggressive or not, Chambers knows what to do when the bullets start flying and Porter doesn’t.

MG: Absolutely. Combat is a lot more, as Jack learns, than theory and strategy and tactics. There’s a real raw, visceral leadership style that Chambers has, and not only do the men start gravitating toward him but Jack starts gravitating towards him too. The Army and the Marine Corps, frankly, need more Chambers than they need Lieutenant Porters. But they need Porters too, and they need them to stand up and say something when these morally questionable dilemmas are posed.

PK: Chambers exemplifies a particular type of physical courage, one that is admirable and clearly necessary in the Corps. Jack, as a young man at war, wants to live up to that standard of physical courage that we think of most readily when we think of warfare, but his true trials test his moral courage far more than his physical courage.

Moral acts of courage tend to come from a different place. They don’t happen in a moment, with a burst of adrenaline. They requires thoughtfulness, time.

MG: Moral acts of courage tend to come from a different place. They don’t happen in a moment, with a burst of adrenaline. They requires thoughtfulness, time. And then you make a decision and keep going. There are many cases where he maybe made the wrong decision, and that’s going to carry consequences, for him, for the Iraqi townspeople, for his soldiers, for the war effort as a whole. It’s so easy, in our culture, to criticize after the fact. But it’s never so easy in the moment, when everything is confounding. You think the only thing you can trust is yourself, but after 48 hours of no sleep, three different conflicting stories, and a subordinate that you want to trust but cant, how do you figure out what right even looks like. Often there are no clear answers. And that is such an inherent part of counter-insurgency, both for the occupiers and for the occupied. I think that’s true even for Chambers, who is the ultimate consequence of sending young men and women to war over and over again. He has done everything in his power to bring his men home — what more could you want from an NCO? But that kind of attitude can prove very dangerous, especially in a Wild West environment like the fictional town of Ashuriyah in Youngblood. Ashuriyah’s right on the sectarian fault line between Baghdad and Anbar Province, so these questions and consequences are happening in a potent, dynamic environment that’s difficult for any stranger–no matter how smart or accomplished–to grasp. Even Chambers seems baffled by it at times, and he’s been there before.

PK: Reading the novel, you understand why Chambers provokes both love and awe in his men. Jack may be essential for keeping them on mission, but Chambers is the one that really bonds them together as a unit. In the scenes with him, you can seen some of the deep satisfactions someone can get from time at war.

MG: War can be hell, but if war was nothing but hell it wouldn’t perpetuate. War nostalgia is a very old, time-honored tradition. It’s what led to the Red Badge of Courage, Crane interviewing these Civil War veterans who were dying off, wanting to tell their stories. Our friend Elliot Ackerman has written about nostalgia for war, about the type of veteran who is gravitating toward the Middle East now, to be closer to it. Jen Percy just wrote about veterans fighting ISIS, trying to respark something.

PK: Respark what?

It’s not just the adrenaline or the thrill that keeps drawing people back to war. It’s that clarity of being. It’s intoxicating.

MG: That sense of purpose, that clarity of being. It’s a common refrain for vets of Iraq and Afghanistan. America is this great, moneymaking empire that does a lot of good things but can be confusing and messy. Going through combat with good individuals on either side of you, doing that patrol, accomplishing that mission. Doing that every day, every night, with a tribe of like-minded souls who have your back, literally and figuratively … It’s not just the adrenaline or the thrill that keeps drawing people back to war. It’s that clarity of being. It’s intoxicating. I know I have not experienced anything like it since I got out. And I love writing. I found a sense of purpose back here at home that some of my peers are still looking for. But I think it’s a natural thing. It’s also something easy to say when you come back with all your limbs, all your faculties. I imagine some conversation down at Bethesda my have a darker tinge to it.

PK: And that purpose is part of why we joined in the first place.

MG: Looking back at it later it almost seems quaint, but people who joined after 9/11, it very much felt like a calling. We were attacked. Innocent civilians in our home were attacked and killed. Joining is something I’m proud of, as an individual, and it’s something I feel pride for in anyone who signed up. But fast forward a few years later and you’re occupying a country, wearing fifty pounds of body armor, wearing black Oakley sunglasses, realizing that the Iraqis are looking at you like what you are…a martial occupier…

PK: Those Iraqis get a lot more of a say in this book than they do in most American novels about the war.

MG: When I set out to write Youngblood. I kept thinking about inheritance. A cumulative inheritance. I wanted to write a book that, if it didn’t cover the entirety of the Iraq war, covered a large swath of it, something that was more than a slice of life. I’d already written a slice of life story with Kaboom. And as I figured out a way to do that larger story, the idea for a bi-level narrative came to mind. Setting it near the withdrawal made a lot of sense, so I could reference the entirety of the war. But also having that mystery part set during the height of the sectarian war made a lot of sense, too, because in many ways that was the fulcrum of the American experience in Iraq in 2003 to 2007, where everything changed and didn’t change simultaneously. Having that mystery set there, and having Jack and his soldiers encounter what had happened a few years earlier, felt important.

It wasn’t a possibility for me to reconcile all those things and form a coherent narrative without prominent Iraqi characters.

Also, the one continuity in these towns, in these villages, as the insurgency and the counterinsurgents were playing out against each other, was the Iraqi civilians. Every year units would rotate in and out. There’d be new commanders. New power players. New American moneymen. But the sheiks didn’t change. The imams didn’t change. The guy that sold ice at the corner didn’t change. The insurgents, unless they were captured or killed, didn’t change. So having them be an important part of the narrative was not just vital, it was inevitable. They’d been there through the duration. They’re still there, dealing with what we wrought in 2003. It wasn’t a possibility for me to reconcile all those things and form a coherent narrative without prominent Iraqi characters.

PK: You’ve been heavily involved with the veteran community — you worked for Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, you co-edited an anthology of veteran writers called Fire and Forget, and now you’re working at Words After War, which is a writing NGO specifically designed to address the civilian-military divide. I wonder what your sense is of the current civilian-military divide. Are we getting better? Are we backsliding?

MG: It’s tough to say. In some ways, in the center of the storm, I want to say we’re getting incrementally better. Certainly that’s what I see every week at the Words After War writing workshops, where vets and civilians wrestle over issues of war and conflict in literature. They learn from each other, they better one another’s work, they argue and debate and find common ground. It’s fucking inspiring. Then I go home and see polls like the one about Millennials being pro-Syria invasion as long as they don’t have to fight themselves, and wonder if we’re all just pissing into the wind, to use that beautifully poetic Irish phrase.

PK: Watching the course of the war, the sheer horror of what is happening to the Iraqi people, and contrasting that with the level of the political dialogue about war here can certainly be intensely frustrating. In the book, you describe one character, saying, “A broken nobility was all that he had left.” What’s the state of your nobility these days?

My understanding of our generation of vets is that we were idealists. And for many of us, that idealism has been broken…

MG: Personally? I just wrote a book, and I think once you finish a book you have nothing left, to include nobility. Good bad or indifferent, that just matters to me less now. I think, writing, finding a new purpose was immensely helpful in that way. I know it’s something a lot of veterans of our generation are trying to reconcile with. My understanding of our generation of vets is that we were idealists. And for many of us, that idealism has been broken, not just by the rigors of war but by the ways these wars have been carried out, the immensely complex moral ambiguities of these wars, and just growing up. That broken nobility of Chambers reminded me of a lot of people I know, and have great admiration for. Both for their service, and for their capability, when they were in that service. But I think a lot of us, when Chambers is having that moment, it’s a reckoning. It’s something I wish more of us were talking about, I think America as a whole needs to have a reckoning with how Iraq played out. To see that reckoning largely being dealt with largely by twenty and thirty year olds who gave the best years of the lives to this effort is largely dispiriting. To see that reckoning still being dealt with in an incredibly brutal way by the Iraqis, over ten years after we told them we’d bring democracy, it’s tremendously dispiriting. Both of those things were part of the drive for me to keep rewriting Youngblood, even when it wasn’t very good, the desire to get a larger share of the country to deal with it. Because we didn’t just wear our unit patches out there, we wore the American flag. If you paid your taxes, we were representing you, even if you don’t feel like you were.