Craft

A Tale of Two Author Photos: Gender, Race and the Body Represented

by Nayomi Munaweera

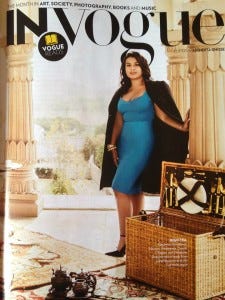

In 2013 I was in India for the Jaipur Literary Festival and by some adept maneuvering my publisher scored me a photo shoot in Vogue India. The concept was for three debut novelists to be photographed in couture and jewels in a Jaipuri palace. The writers would be Samantha Shannon, the British paranormal and dystopian novelist, Deepti Kapoor, author of A Bad Character, which was soon to be released, and me.

Vogue picked us up from the festival and whisked us through some of the bleakest and most poverty-strickened landscapes I had ever seen to a palace turned hotel. In a five-star room, they poured me into a teal bandage dress that was so tight it did not close up in the back; giant binder clips and prayers were employed to ensure that the dress did not explode mid-shoot. My feet were stuffed into totteringly high and pointed heels, my face was painted and my hair teased big. A jeweler appeared with his bodyguard in tow. He opened steel cases to reveal Rajastani gold and gemstones that glittered in the dark room. The stylist picked out a few pieces that had cost more money than I had made in my life. She slid these onto my wrists and fingers.

Four hours of meticulous prep later, I walked very carefully out onto the set. It had been set up as a tea party. We would be three writers interrupted at tea and photographed in all of our glorious candor, because you know- writers always get dolled up and drink tea in the afternoon. It’s a secret but daily and necessary writer ritual. (If you are an aspiring writer-take note. This is how the magic happens.)

The photographer looked at me and said, “ah a big girl.”

He sighed, he fussed and fretted about what to do about my arms which are the opposite of Michelle Obama arms. The Vogue team brainstormed and then threw a cape over my shoulders. Problem solved, scary arm flesh hidden away, photo shoot saved.

I’ve struggled with body image issues all my life. I grew up in Sri Lanka and Nigeria. I’d been a skinny infant among with other skinny infants in Sri Lanka, a fat child amongst skinny Nigerian children and a lumbering adolescent amongst svelte Sri Lankan girls in Sri Lanka when we went back for vacations. A well-meaning aunt’s nickname for me growing up was “Bursting At The Seams.”

At twelve moving to America and impending puberty precipitated a sudden and dramatic weight loss. Since then I’ve flipped and flopped between a size 8 and a size 10. I’ve heard the ubiquitous, “You’d be so hot if only you were 10, 20, 30 pounds lighter” numerous times. Sometimes this voice comes from the outside but often it speaks from within my own head. Sometimes, I’ve whittled myself down to a size 4, mostly by not eating much. This shape-shifting and estranged relationship with my flesh is what it means to live in a world where my primary worth is measured by the shape and size of my body.

When the Vogue India issue came out my friends didn’t recognize me. I barely recognized myself. I had been slimmed down, whitened several skin shades and given a sort of pig nose. I had to convince friends that this was really me. It is an uncanny experience to see oneself on the pages of a glossy international magazine, especially when the self presented is that of a perfectly feminized, sanitized, glammed-up stranger.

More than this, the irony was glaring. My novel, the one that had landed me in the pages of Vogue India is about two women caught in the atrocities of war. It is about what happens to the female body in the context of terrible conflict. One of my characters deals specifically with the discrimination that dark-skinned women face worldwide. My project, (as much as I could have said I had a project while writing) was a feminist one. This is something that the review of my book accompanying the photographs got right. The author even includes this sentence, “The novel is negotiated through two female narrators… Munaweera stresses telling stories from a feminist perspective.” And yet the pictures accompanying this article were decidedly not feminist.

Did I regret doing the shoot? No, of course not. I was a debut author with a book that had taken me seven years to write and another five years to place with a publisher. In that situation when Vogue India calls, one does not say no. Instead one gives thanks to whatever gods of publicity have made this miracle possible and shows up to the shoot bright and early.

Then too, as someone who spends most of my days writing in a threadbare pink robe and unwashed hair, it isn’t the worst thing in the world to be occasionally viewed as a glamorous cover-girl.

I don’t know how many books the Vogue photo shoot sold. I’m guessing not many. But it does pop up every now and then. Recently I spoke at a large Californian university where the students had read my book for their core curriculum. In the introduction the professor mentioned the Vogue shoot and there was a flurry of interest from the students, most clearly the female students. They liked my book in which women deal with war, love, violence, and migration but the magic word, “Vogue,” raised my estimation immeasurably.

A few months ago the online magazine Wear Your Voice approached me with a request to participate in a very different kind of photo shoot. The concept was to recreate the famous Dove ad that had pictured plus-sized models in white underwear with women of color, trans-women, differently-abled women, women of size etc. The Dove ad itself had been a commentary on the ultra-thin models employed in a Victoria’s Secret campaign. Wear Your Voice aimed to draw attention to the fact that even greater diversity existed in the world but that the media often ignored female bodies that did not conform to a certain narrow definition of femininity.

If I said yes to appearing in this shoot there would be no fancy clothes, no bling, no photo shopping, no Rajastani palaces, tea services or forgiving capes to distract the eye. There would just be a white backdrop, white underwear and bare skin. It was terrifying.

If the Vogue shoot had exposed the fear of not being presented as the self the Wear Your Voice campaign presented the exact opposite fear.

What would it mean to bare the self without the soft landing of digital manipulation? What would it mean to face the self unadorned?

In addition to these questions I had concerns about safety. I come from a culture in which women’s bodies are meant to be covered, where female chastity is prized above all other qualities. The magazine had asked a few other South Asian women to do this shoot but none of them had agreed. I understood why they would not. I had the same questions that probably made them refuse. Would being photographed half-naked be taken to mean that I was dishonorable in my home culture? That I was asking for sexual attention or that I was too Americanized? Simply put: would I be seen as asking for it?

And then there were the literary questions. If I appeared in my underwear what would people assume about my literary capabilities? Would I be written off as a publicity whore? Someone who would do anything to bring attention to her books?

Despite all these concerns I agreed to the shoot. And then I thought about cancelling a hundred times. I emailed my publicist bullying her with questions about whether participating would “hurt my image.” The second time, she said, “Only do it if you feel like it…” I asked my husband if I should do it and he said exactly what I knew he would, “Of course, if you want to, do it.”

I had been hoping someone would tell me not to do it for some good reason. But there was really no good reason and I had to grapple with the fact that I was balking for deep-rooted body-issue reasons and for the fear of possible repercussion. These were of course exactly the issues that the photo shoot was attempting to challenge.

On the day of the shoot, I showed up at an Oakland warehouse that was as far a cry from a Japuri palace as is possible and found myself in the midst of a crowd of women. We sat around and slowly, shyly shared stories. Quickly it became obvious that everyone was terrified about what we were about to do. One woman said that her conservative Mexican family was going to freak out when the pictures came out. Another whizzed around in her electric wheelchair and worried about how folks would react to her body, one almost never seen in this way, bared, and beautiful. A trans-woman talked about transitioning just eighteen months before and being bowled over by how much people attempted to police her now female body. She perhaps more than anyone had insight into how desperately the culture wanted to control femininity. Each woman I talked to had decided to participate despite what their families, their loved ones and society had told them about the value of their bodies.

We got in our white underwear; we did our makeup and hair. We watched as each woman took her turn in front of the camera and did her best to be as natural as she could be. Then we got together for group shots, our bodies close, sometimes playful, sometimes sultry. And yes, it felt warm, felt loving, and empowering. We were allowing a culture that shames and hates certain bodies access to our bodies. We were being vulnerable and ultimately that vulnerability felt powerful.

The Wear Your Voice photo shoot came out a few weeks later. I loved the pictures. They showed us as we were in all our varied loveliness.

We looked proud; we looked happy. We looked like real live human beings.

The campaign started out quietly and then it went viral, appearing in publications around the world. There were of course plenty of hateful internet comments. But for each of these there were many more from women and girls thanking us for showing them bodies like their own, for making them see themselves too as possibly beautiful.

I went to a party a week later. A friend asked me about the shoot and I was showing him the pictures when someone else that I did not know also looked over and said, “Why did you do this?” I said, “Because we are trying to change how culture views the female body.” He said, “That’s a useless cause. Body standards will never change.” I have to disagree. I think it’s important to keep knocking at the door and asking for change, asking for inclusion. I think that as we keep doing this change is not only possible, it’s inevitable.