Craft

On Not Writing: An Illustrated Guide to My Anxieties

by Ingrid Rojas Contreras

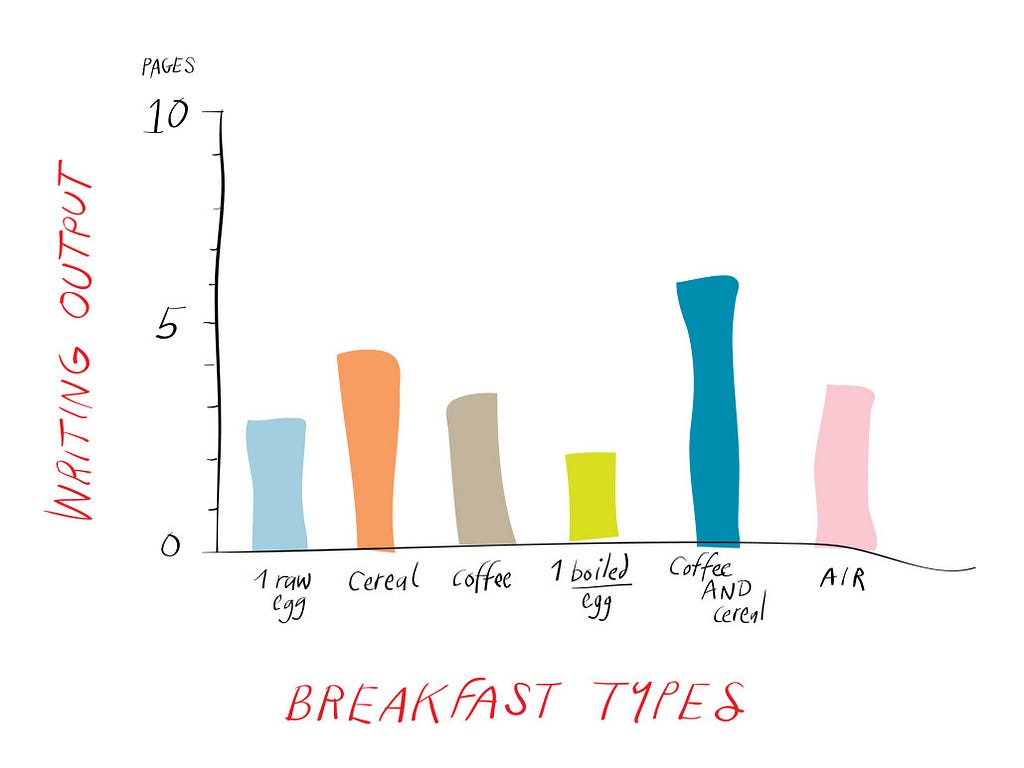

I experimented with food and sleep in order to find out the combination that left my mind and body feeling sharpest. I mustered up schedules in order to fit writing into all manner of work-related circumstances — grant writing days, copyediting days, transcription days, translation days. And for those unicorn days in which I had nothing else to do but write, I made schedules for those days too. I time stamped everything.

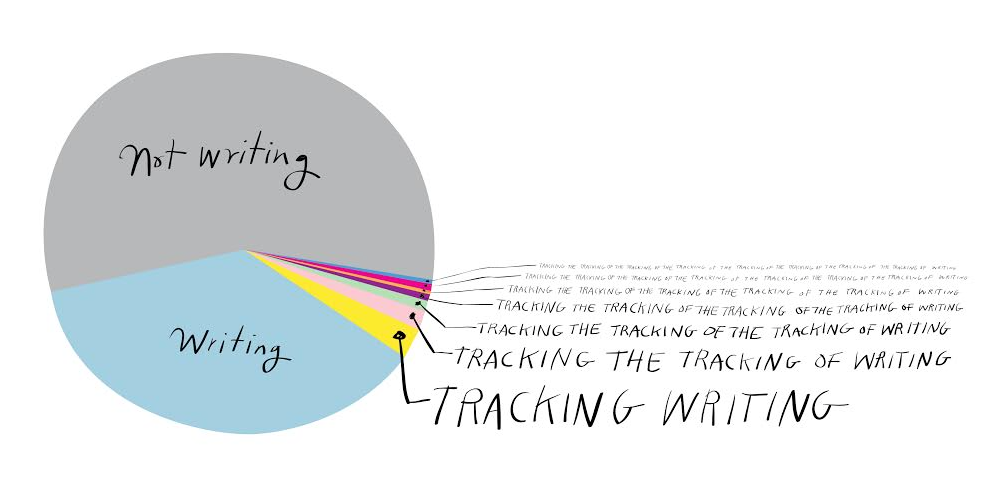

(As a joke to myself, I once started a meta chart, where I tracked the time it took me to track myself, then the time it took me to fill in the meta chart, then the time it took me to fill the slot indicating how long it had taken me to fill in the meta chart.)

The theory was that if I could figure out the science to writing, I would be able to create the right circumstances needed in order to land on my desk at the allotted writing time feeling refreshed, unblocked, and inspired.

Like a horse beginning a sprint at the sound of the starter pistol, I would write word after word, sentence after sentence, in glorious lap after lap of stirring storytelling.

But no amount of tracking, experimenting, and planning that I ever came up with kept me from the black eventuality of sitting down to write and nothing coming out.

There would be my mind a sheer blank, and there would be the white page so silencing.

I would sit in wait for an average of five minutes, fifteen seconds.

Then I’d turn to my journal in order to complain in all manner of metaphors about my lack of inspiration — the well run dry, the block, the free diver run out of air.

Then it occurred to me: What if in all my years of tracking, I had been keeping track of the wrong thing? What if instead of charting those hours that tangibly resulted in the creation of articles, stories, chapters, essays, what if instead it was more accurate to keep track of the types of writing I do that you will never see but are nonetheless necessary to produce the work that you do see? Isn’t that type of writing more important?

Because, see, writing about not writing is also writing.

But what else is writing?

All the hours I spend in the back of my throat, flexing my tongue, agonizing in unwritten sentences — is that writing?

What about the pen poised over the blank page, the fingers suspended above the keys overcast in the jeering electric light of the screen? Is that writing?

Is sheer inertia writing? Is sheer potential writing?

Is signing my name to a check writing?

Is making a list — buy the milk, the cereal, the frozen fruit, the greens — writing?

What about thinking — Oh, I could have written that — is that writing?

Is transcription writing? (Allow me to transcribe here part of that gem of Borges short stories Pierre Menard Author of the Don Quixote as flimsy defense, “[Pierre Menard] did not want to compose another Quixote — which is easy — but the Quixote itself. Needless to say, he never contemplated a mechanical transcription of the original; he did not propose to copy it. His admirable intention was to produce a few pages which would coincide — word for word and line for line — with those of Miguel de Cervantes.”)

And what if one notices a detail, composes a sentence in one’s head, but later forgets to commit it to paper and then the sentence is gone? Is staring at the departed silhouette of that sentence, the blank space in your mind that holds all the dark — is that writing?

So much of not writing is actually writing. A writer at rest may at all times be imperceptibly writing. It’s possible even that the type of writing that we do that you will never see in order to produce the writing that you will see, it’s possible that this type of writing happens at all hours and even in sleep.

The more I look at this line differentiating writing between not writing, the more this line disappears. Maybe there is no such thing as not writing. Maybe there is no such thing as the block. Maybe there is no such thing as an accurate chart that can show the real effort that goes into writing. Maybe the only accurate thing is to just look at the face of a writer — at the haggard lines, at the skin luminous with triumph — you can see the effort there.

Originally published at electricliterature.com on February 19, 2016.