interviews

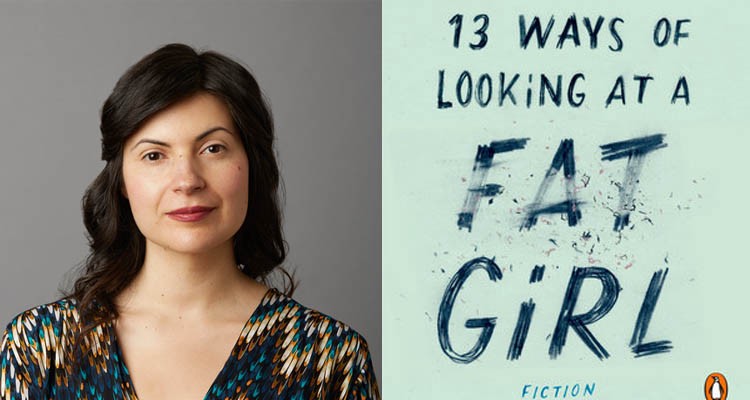

We Do Adjust Our Reality for Other People: An Interview with Mona Awad

by Melissa Ragsdale

“If That’s All There Is” is featured in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading with an introduction from Laura Van Den Berg. Mona Awad’s debut collection, 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, will be is now available from Penguin Books.

Melissa Ragsdale: This book is very much about how a woman perceives herself and how the outside world perceives her. Often we talk about the “male gaze,” but Lizzie is constantly aware of many other gazes too. For instance, in the taxi scene, we see her torn between reacting for Archibald and being polite to the taxi driver. How did you approach gaze while writing?

Mona Awad: I think that’s a large part of the reason I chose the title 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl. It seemed like a very appropriate way of approaching the story of a woman whose self-perception and whose body image is really informed by not by one gaze but a number of gazes, male and female, real and imagined. So much of Lizzie’s struggle is bound up in how she sees herself and how she imagines others see her. It was very important to me that Lizzie’s struggle not be bound to any one gaze. That moment in the cab with Archibald is just such a moment when gaze is about want. Imagining what others want and trying to be that for them. It’s exhausting. It’s disorienting. And you can really lose yourself. For this character, throughout the novel, that’s the impending danger.

MR: In “If That’s All There Is,” we see Lizzie develop a fascination with Archibald, despite the fact that she doesn’t particularly enjoy him (sexually or otherwise). What draws Lizzie to Archibald?

MA: It was important to me to explore how body image can distort our sense of our own worth as humans. We all want to be attractive and Lizzie is drawn to Archibald because he sees her that way. The danger however, is that she doesn’t value herself to begin with, so when he begins to treat her poorly, it doesn’t matter. She clings to him all the same, in part because she is clinging to the part of his gaze that sees her fondly. It doesn’t even matter that it’s destructive. There is something too, I think, in Lizzie, of the masochist.

MR: Mel has a presence throughout the book and Lizzie’s life, though it waxes and wanes throughout. In this story we see her in close quarters with Lizzie as her roommate, often painted in a place of judgement. For instance, Lizzie adjusts how she refers to Archibald in front of Mel, only adding “sort of” after “boyfriend” when Mel is within earshot. How does their dynamic feed into Lizzie’s personality?

MA: I think Lizzie’s relationship to Mel is important throughout the book. Lizzie is embarrassed by Archibald, knows on one level, that he isn’t good for her. But she proceeds anyway, and it’s embarrassing to acknowledge, especially to her best friend. It’s a guilty secret she’s ashamed to admit. I think we do adjust our reality for other people.

MR: Each of these stories zeroes in on a specific moment from Lizzie’s life, and we see her character bloom in new ways with every piece. How did you find these particular moments to explore?

MA: I wanted to really complicate all the ways in which fatness or body image affects our lives and our relationships: with lovers, sex, food, friends, family, clothing, and always, inevitably with ourselves. I also wanted to document how those dynamics change or don’t depending on our size or how we see ourselves in relation to others. So I chose moments/encounters that really illustrated this. I knew I needed an encounter with a thin friend when Lizzie is fat. I knew I needed one with a fatter friend when Lizzie is thin.

MR: This book explores identity, self-esteem, and body image, all hot-button issues in today’s society. Lizzie is constantly aware of her weight, and we see how her awareness and anxiety affect her life. In your eyes, is this behavior specific to Lizzie or is it a more pervasive tendency? Does this book have a message?

MA: I’d like to say it isn’t pervasive, and perhaps I’m too close to the situation because I’ve been exploring this subject for a while, but when I overhear conversations between women at bars, restaurants, in change rooms, I think it’s even more pervasive than I initially even thought.

In terms of a message, I think my hope is that it provides what a story or song provides, for people to feel a sense of connection, for people to feel less alone. I wrote Lizzie with as much honesty as I could in the hopes that I would provide that sort of connection for the reader. I think what I wanted above all was for women and men who are struggling with these issues, not to feel alone.

***

Mona Awad received her MFA in fiction from Brown University. Her work has appeared in McSweeney’s, The Walrus, Joyland, Post Road, St. Petersburg Review, and many other journals. She is currently pursuing a PhD in creative writing and English literature at the University of Denver.