interviews

Jack Pendarvis on Movie Stars, Annie Hall, and The Small Ghost Donkey That Defines Us All: An…

J

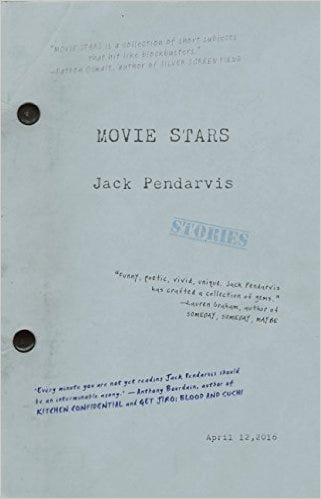

Jack Pendarvis’s new story collection, Movie Stars, is out April 12th from Dzanc Books. Pendarvis writes for Adventure Time and recently put out a work of non-fiction called Cigarette Lighter, but it’s been a long wait for a new book of fiction (his novel Awesome was released in 2008). As a fan, I couldn’t be more excited. These sixteen stories are hilarious first and foremost, but they’re also tender and kind and melancholy. They’re infused with the sort of dreamy wonder that only a good-hearted genius like Pendarvis can access. Movie stars like Bob Hope, Joan Crawford, Jerry Lewis, and Scarlett Johansson haunt the lives of the characters in these stories, as do movie memories. Everything these folks do has been shaped and continues to be shaped by what they’ve seen in movies, lending the whole collection an atmosphere of cinematic yearning. There are also cats in these stories. Lots of cats. If I had to give you one sentence that summarizes the overall spirit of the book, it would be this from “Duck Call Gang”: “I worry about all the little cats out there in the world.” Or maybe, from “Jerry Lewis,” this: “He had a bad day and couldn’t get any turds painted.”

I met Pendarvis at a coffee shop in Oxford, Mississippi, where we both live. He’s one of my writing heroes, a former teacher and someone I’m glad to call a good friend. Two guys at the table next to us were having a religious meeting where they used phrases like altar call. The staff was inexplicably blasting Billy Joel over the house speakers. Before I got there, my five-year-old son had told me that he believed his spit was full of escape pods.

[Read Pendarvis’ “The Black Parasol” in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading.]

William Boyle: Movies are a unifying force in these stories. How did movies shape your life as a kid in Alabama?

Jack Pendarvis: There are different ways I came to movies. One, of course, was seeing them in the theater, especially things like The Aristocats (not to be confused with The Aristocrats) or The Biscuit Eater, which was a Disney movie about a rascally dog. And there were a lot of old movies on TV. I guess they were cheap to program. A bunch of Abbott and Costello movies. Tarzan movies — that’s in the book. There’s one traumatic memory of a Tarzan movie, which comes from my own life. They’d show things like Shirley Temple movies early on Sunday morning before church. Also, when I was a kid, I got a big coffee table book called The Great Movies by a guy named William Bayer. He was writing about movies I hadn’t seen at all. I was just looking at pictures. I read that book over and over. It was shocking. There was a picture of the Last Supper scenario that Buñuel does in Viridiana, and there was a matching shot from Robert Altman’s MASH. (I’d see Altman movies a lot on TV too. California Split came on a lot for some reason.) When I saw these matching shots — really blasphemous shots that imitate the Last Supper — it was kind of shocking and seemed taboo to me. You know, I was a Southern Baptist kid. I couldn’t believe that people were messing with the iconography that way, but it was also fascinating to me, and I wanted to know more about these people that were engaging with this stuff.

When I went to the University of South Alabama — uh, you can’t put that it in there, yeah you can, I don’t care — I went down to this smelly basement and they had tapes — I don’t know if they were VHS tapes or what — but you could go down to this really damp, moldy basement and watch movies. I watched Rules of the Game for the first time in that smelly basement. The Magnificent Ambersons, which Bayer talked about. Things that I’d just only heard of. And then I’d sneak into film classes. I saw Boudu Saved from Drowning and Hiroshima Mon Amour that way. VHS introduced a bunch of new movies to me. I remember you could go to the Phar-Mor drugstore in Mobile and rent a movie for 65 cents and keep it for as long as you wanted. And they had a really strange selection, like Under the Volcano and Harold Pinter things, you know, just lots of weird movies and foreign movies. That was revolutionary. I did see a David Lynch movie in the theater. I took a date to see The Elephant Man in high school. That’s not a good date movie when you’re in high school! We had to sneak out to see the rest of Private Benjamin, which was playing in the next theater. To be clear: When I talk about my childhood, I could mean anywhere from about age 10 to age 30. I’m serious. It all blurs together.

WB: Was there a movie experience that you had early on that was transformative — like you were too young for that movie and it changed the way you saw the world?

The ticket-taker said, pointing to other side of the theater, “In that movie, they do it. In this movie, they talk about it.”

JP: My brother talks about walking into our parents’ room and The Innocents was on and he saw a bug crawling out of a little cherub statue’s mouth and that it scared him to death and only years later when he was an adult he saw that scene again and realized what it was from and it freaked him out again. A movie I saw too early that had a big impact on me was Annie Hall, which came out in ’77. I was 13 or 14. I went to see it with my friend Franklin Tarelton, whose father had been my father’s high school football or baseball coach. We went to a place called the Airport Twin Cinema, which had two screens, on Airport Boulevard in Mobile. On the other screen was a soft-core movie that was very popular at the time. Something like Emmanuelle 3. And I was such an earnest 13/14 year old that I asked the cashier about Annie Hall: “Is this movie okay for us to see?” The ticket-taker said, pointing to other side of the theater, “In that movie, they do it. In this movie, they talk about it.” I felt nervous, but we bought the tickets. I was like, I guess I can handle that. I understood hardly any of the jokes, but it really made a huge impression on me. I think I mostly understood the slapstick.

WB: That was your first Woody Allen movie?

JP: I might’ve seen Sleeper on TV by then. It used to come on a lot. I’d already read some of his prose collections, Getting Even and Without Feathers. So I knew about him. It’s weird to think about now, but everyone knew about him then. He was quite famous and popular. I remember the woman who drove our car pool saying, “He’s a genius, but I don’t approve of him.” I liked the slapstick in Annie Hall, the way it was cut together, the imagination. It was instructive. I wanted to be a writer even back then. I loved James Thurber and I saw a connection between the kind of humor James Thurber wrote and what I was seeing on the screen. I associated it with New York, The New Yorker, that whole world I was fascinated by. I was too young. I mean, anyone else could’ve handled it, but I was a very young 14.

WB: Most of the stories in Movie Stars are set in Mississippi, but “Cancel My Reservation” takes place, in part, in Los Angeles. I’m assuming that movies influenced how you thought about place too? Your first impressions of New York and Los Angeles would’ve been through Woody Allen, through movies?

JP: My first impression of New York was probably from reading James Thurber and reading about James Thurber. I read a lot of stuff about New York. I was fascinated by Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley and all those people. Ugh, I sound like just a horrible kid. So my impressions of New York were really like in Radio Days — which came out much later, obviously — when it shows the little kid listening to the radio and the elegant people in their penthouse eating breakfast, that sort of thing. I recently watched the Michael Ritchie movie Smile, which came out in ’75. Seeing it now, that movie looks so much like my childhood, even though it takes place in California and I grew up on the Gulf Coast of Alabama. The people, the buildings, the cars, everything. If you want to see what it looked like when I was a kid, you should see Smile.

WB: Since your formative movie-watching years were the ‘70s — this kind of golden age of filmmaking — did that generally shape how you write and think?

And we went to see The Deep, which was a distressing thing to see with your parents because Jacqueline Bisset brought out certain feelings I didn’t feel comfortable experiencing with my parents around.

JP: Well, I wasn’t going to see Taxi Driver when it came out. I was going to see things like The Biscuit Eater. I saw Smokey and the Bandit in the theater. I couldn’t believe all the cursing coming out of Jackie Gleason’s mouth! I kind of indignantly walked up the aisle and I expected my parents were going to be soon following in similar haughty indignation and they were just still in there and I was like, This must be okay, and I went back and watched the rest. And we went to see The Deep, which was a distressing thing to see with your parents because Jacqueline Bisset brought out certain feelings I didn’t feel comfortable experiencing with my parents around. And then, let’s see, I remember going to see The In-Laws with my parents. That was a wonderful movie-going experience. I’m talking about the original, with Peter Falk and Alan Arkin. That was a huge experience because my parents loved it so much and they were laughing and I was laughing. We all thought it was hilarious. That was a nice bonding experience.

WB: But you don’t think your taste wasn’t shaped by that specific ’70s aesthetic?

JP: I mean, I did see California Split, Smile, Cotton Comes to Harlem, and things like that on TV. I’m sure it seeped in there. And The In-Laws, Smokey and the Bandit, Annie Hall — those are all ’70s movies. I was getting a good dose of that. But the first Scorsese movie I saw in the theater, for instance, was After Hours in ’85. I was pretty ignorant about a lot of things. The Blues Brothers had a big impact on me too. I went to see it with my most religious friend. It had a lot of what I thought of then as blasphemy in it. But, at the same time, the scene with James Brown, that was uplifting spiritually. Saturday Night Live certainly gave me permission in new ways. The movies I went to see that pushed me into the Devil’s Crew were starring people I’d seen on SNL like Chevy Chase, Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd, and John Belushi

WB: Another thing that unites these stories — though they’re all hilarious — is melancholy. For me, as a kid, watching movies compulsively was often sad as hell. Do you see a connection between movies and melancholy?

Movie characters are these vessels you can pour your own emotions into.

JP: Movies are supposed to be social, but I guess a lot of my characters are watching movies by themselves. I find that to be an enjoyable experience. Sometimes I like it better. I remember crying at the end of Shane the first time I saw it. And then I showed it to some of my friends in my 20s and they were just laughing. Same thing with Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast. I didn’t cry, but I thought it was amazing. Then I showed it to some friends of mine. Every time the Beast came on screen, these two young women would say, “Courage!” like the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz. It was really getting on my nerves. So, I enjoyed that movie a lot more when I watched it by myself. I’m ambivalent, I suppose. I like watching movies by myself or with my wife. We have a similar frame of mind about movies and we enjoy the same things. It’s fun to watch a movie with her. In the book, one guy’s watching a Joan Crawford movie after his girlfriend’s just left. Movie characters are these vessels you can pour your own emotions into. If you want to think about the melancholy/lonely aspect, there are guys like the narrator of the story “Pinkeye” who’s imagining he can be a henchman in a movie. He’s projecting himself into a movie.

WB: There’s a lot of that. It’s funny, but it’s sad too. When you grow up watching a lot of movies, a lot of your knowledge comes from movies. You think of projecting yourself into a movie or when you see someone do something it recalls a movie memory. Your characters are always thinking that they’re doing things “like in a movie.”

JP: Movies actively — almost perniciously — encourage that. Think of Sherlock Jr. with Buster Keaton or even The Last Action Hero. Movies encourage that kind of identification. I guess fiction does the same thing. Not mine. Somebody’s. Think of Mary Katherine Gallagher in Superstar. I think that movie is an accurate portrait of a melancholy film fan.

WB: There’s a lot of facing down mortality in the book too. In “Duck Call Gang,” for instance.

JP: After that story came out in McSweeney’s, our friend Elizabeth Kaiser was concerned about me. Because, you know, they put it in the letters section. So, I think, maybe it was worrying. But it’s pretty close to documentary, I suppose. I made up the part about a gang that blows on duck calls.

WB: There are other narrators that think about getting old and dying in the way that narrator does. And that’s tied into the horror influence in these stories. There’s your take on the ghost story here, but also people are kind of haunted by their own mortality and there’s an awful lot of dread.

JP: What’s the point of writing if you can’t put in a little of that feeling that we all have that there are invisible people watching us? Don’t we all have that feeling? Or that we’re all kind of walking a line between two worlds? Aren’t we all walking a line between two worlds?

WB: The epigraph is from a book by called The Ghost World.

That’s the way I feel all the time, split between, ‘Oh that thing looks like a funny donkey’ and ‘Oh no, now that I saw it I’m going to die.’

JP: A book I found at the University of Mississippi library. Not the Daniel Clowes graphic novel. A book from 1893. It says: “In the neighborhood of Leeds there is the Padfoot, a weird apparition about the size of a small donkey, ‘with shaggy hair and large eyes like saucers’ . . . to see it is a prognostication of death.” Now what I like about that epigraph is that it’s funny it looks like a donkey — that it’s the size of a small donkey is a funny detail — but then if you see it you’re going to die, which is terrifying. That’s the way I feel all the time, split between, ‘Oh that thing looks like a funny donkey’ and ‘Oh no, now that I saw it I’m going to die.’ That’s my general feeling at all times. And maybe that kind of plays out through the book.

WB: Ha ha ha. It does.

JP: I thought of something. I saw Caddyshack at the theater. It was right after my grandfather died. And I was like, Lord I’m sorry, as I sat there watching a turd floating in a pool and a priest cursing and being struck by lightning. I was like, Any punishment that you give me will be just, Lord. That’s probably what I was thinking as I watched Caddyshack.

WB: What’s the role that nostalgia plays in the book? There are some characters who shun technology, who talk and act like they’re from another time, even though technology is very present in their lives. There’s not a yearning for another time, more of a general out-of-placeness. But maybe they’d be out of place any time?

JP: The narrator of “Cancel My Reservation” might be a nostalgic type, and that doesn’t work out too well for him. But otherwise I don’t think that’s a big motivating factor. I had to go back and add some technology. I always forget that everyone has a cell phone now. So, I might’ve gone back and stuck a few cell phones in so people have the illusion that I live in the present.

WB: To me, a lot of the things I was somehow nostalgic for as kid, came from the movies. Typewriters, record players, old cars.

This is the saddest interview ever. “Ancient Man Manages to Crap Out A Book! 167 pages! Barely a book! But you’ve got to hand it to him because he’s so decrepit!”

JP: I loved those things because they were part of our daily life back then, ha. In fact, I didn’t learn to type until I got my first job. My grandmother showed me where to put my fingers on the keys and I taught myself to type really fast. This is the saddest interview ever. “Ancient Man Manages to Crap Out A Book! 167 pages! Barely a book! But you’ve got to hand it to him because he’s so decrepit!”