Reading Lists

Contemporary Innovators of the Short Story

A Reading List from Rebecca Schiff

There’s something embarrassing about writing short stories. First there’s the word “short,” a word I’ve always associated with my height, with having to stand in the front row in class pictures. I have a nagging feeling that if I were more disciplined, a bigger thinker, or even just taller, I’d have written a novel by now. Maybe I’d have written Herzog for ladies. The problem is that I really like stories. I like the efficiency. I like the things that are not said. I’m a sucker for an epiphany. Most of all, I like that stories are a chance to experiment.

Great novels also experiment and innovate, but a short story can make a never-before-seen formal leap and then peace out, before you’re even sure what’s happened. And we live in a thrilling time for stories — the last half-century, the last decade, the last year. In the past year, I’ve read stories by Paula Bomer, Rebecca Curtis, Greg Jackson, Shelly Oria, Matt Sumell, and Deb Olin Unferth that are strange in all the best way, stories that have excited me as much as anything I’ve read before. These writers are my age. Why are they — we — so bold? We may be less afraid to take chances in our stories because we grew up knowing that we were alive at the same time as writers who took even bigger chances in their stories — Grace Paley, Barry Hannah, David Foster Wallace. I mention these three because they died recently, and so can’t be included on my list, which will just be about the living.

— Rebecca Schiff, author of The Bed Moved.

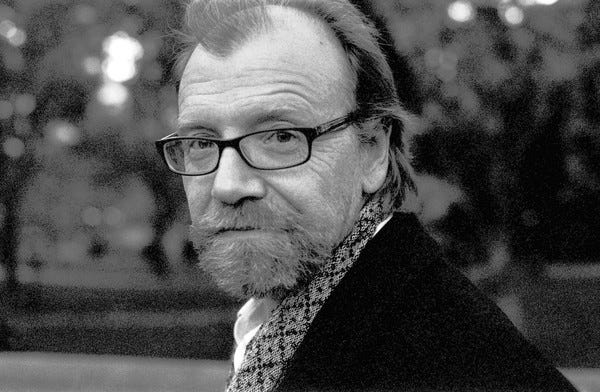

1. Lorrie Moore

This is supposed to be bad, but I learned how to break the rules of fiction before I learned the rules.

For some people, the short story starts with Chekhov. For others, it begins with Hemingway. For me, in the mid nineties, it began with Lorrie Moore. I was wandering under the klieg lights at Barnes and Noble, looking for the next book to get me through adolescence, and a book titled Self Help seemed like a good idea. There was no Electric Literature then to tell me that I would love Moore, that I would age quickly into her demographic (alienated women), that she would wind up mattering to me and a generation of short story writers. This is supposed to be bad, but I learned how to break the rules of fiction before I learned the rules. “Plots,” says Moore’s narrator in “How to Be a Writer,” “are for dead people.” For the living, there are Lorrie Moore jokes, whole pages that just say “Ha! Ha! Ha!”, completely original metaphors, and with them, a new way of seeing.

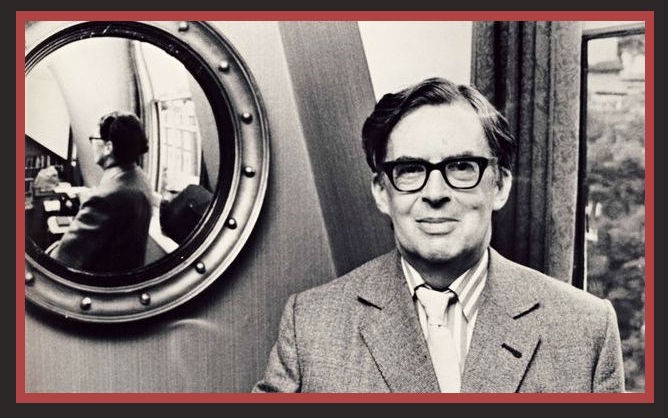

2. George Saunders

I hated the first George Saunders story I read. The story was “Sea Oak,” anthologized in the O’Henry Prize stories of 1999, and it confused and bothered me. “What the hell was that?” I thought, after I finished reading it. “I’m ready to get back to the rest of these stories now. Give me affecting realistic fiction, thank you very much.” Of course I don’t remember the other stories anymore. “Sea Oak” is a Saunders masterpiece, the story of a male stripper and his dead aunt Bernie, who never had anything nice in life and so comes back from the dead to give the narrator some memorable financial advice — “Show your cock.” Saunders has figured out a way to write about poverty in America, to cut through the clichés and sentimentality. “At Sea Oak, there’s no sea and no oak, just a hundred subsidized apartments and a rear view of FedEx.” There’s also a made-up TV show called “How My Child Died Violently,” a title that works because it has both consonance and assonance, for writers who want to learn how it’s done.

3. Joy Williams

Her stories make craziness seem so natural that I’ve become convinced that sanity is a construct…

Things get even darker and weirder in the stories of Joy Williams, whose collected stories came out this year. One of my favorites is about a woman named Miriam who is dating a forensic anthropologist named Jack Dewayne (“[His students] called themselves Deweenies and wore skull-and-crossbones T-shrits to class.”) Jack accidentally stabs himself in the eye mid-story and spends the rest of the story brain damaged, nursed by a student named Carl. Miriam befriends a lamp. The four — Jack, Carl, Miriam, and lamp — take a road trip. Another story of displaced affections involves a man who becomes convinced that his employer looks just like Darla. The employer replies, “This is of no interest to me, but who is Darla?” Darla was a beloved childhood babysitter, and like the lamp in the previous story, becomes more emotionally significant as the story progresses. Williams’s stories take things we think are of no interest to us and make us interested in them. Her stories make craziness seem so natural that I’ve become convinced that sanity is a construct, something we keep around because we are too scared to look (or stab) ourselves in the eye.

4. Alejandro Zambra

Alejandro Zambra is actually around my age, but he lives on a different continent and has already written three novels, three books of poetry, a collection of essays, and a collection of short stories. Maybe growing up under Pinochet gives you a sense of urgency — this needs to be said today in case I’m disappeared tomorrow. Zambra’s stories are urgent but still loose, funny because he has confidence that he is allowed to play. In the title story of his collection My Documents, Zambra writes, “My father was a computer, my mother a typewriter.” I don’t know what this means, but of course I know exactly what it means. My father and mother were the same way. Zambra also has a story called “I Smoked Very Well” where the narrator asserts, “I was good at smoking; I was one of the best.” He tries to quit and fails and tries again. It’s hard to stop when you’re good at something.

5. Sam Lipsyte

His stories take every risk you wish you were brave enough to take, and then risk some more.

Another writer with a smoking story is Sam Lipsyte, though his narrator has “quit quitting them again.” It takes courage to know that something as small as a pack of cigarettes is going to get us to childhood and parent death and lost love, but Lipsyte lets language lead the way to the cancer ward, where the narrator’s mother is dying and everyone is still lighting up. “Bald men, bald women, bald teens sat out in the summer twilight in their gowns. Cut open, sewn shut, garlanded with IV lines, poisoned with their futile glowing cures, they puffed away like wild heroes.” Lipsyte has written three novels, but his two story collections, Venus Drive and The Fun Parts, should make him a wild hero to short story writers. His stories take every risk you wish you were brave enough to take, and then risk some more.

6. Lydia Davis

I’m going to end with Lydia Davis, because I’ve exceeded my word count. Davis rarely exceeds hers. She can do in a paragraph or in a sentence what most writers can’t do in whole novels. “There are also men in the world,” begins a story called “Men.” Davis knows that half of her readers will get the joke. She knows we’ll get everything. I’m not worried about plot or characters when I read a Lydia Davis story. I just want her to do her thing, to play with language and obsession, and to frighten me. You could call her a stylist, but that would be undervaluing style, which in Davis’s hands is so original that it remakes the world.

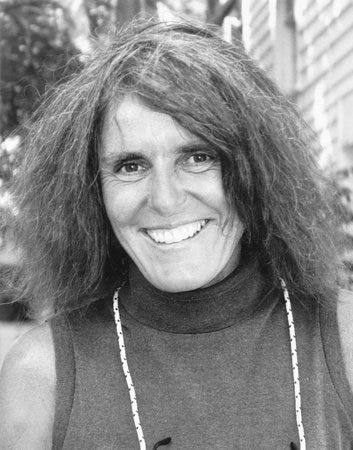

About the Author

Rebecca Schiff is the author of The Bed Moved. She graduated from Columbia University’s MFA program, where she received a Henfield Prize. Her stories have appeared in n+1, Electric Literature, The American Reader, Fence, and Guernica. She lives in Brooklyn.