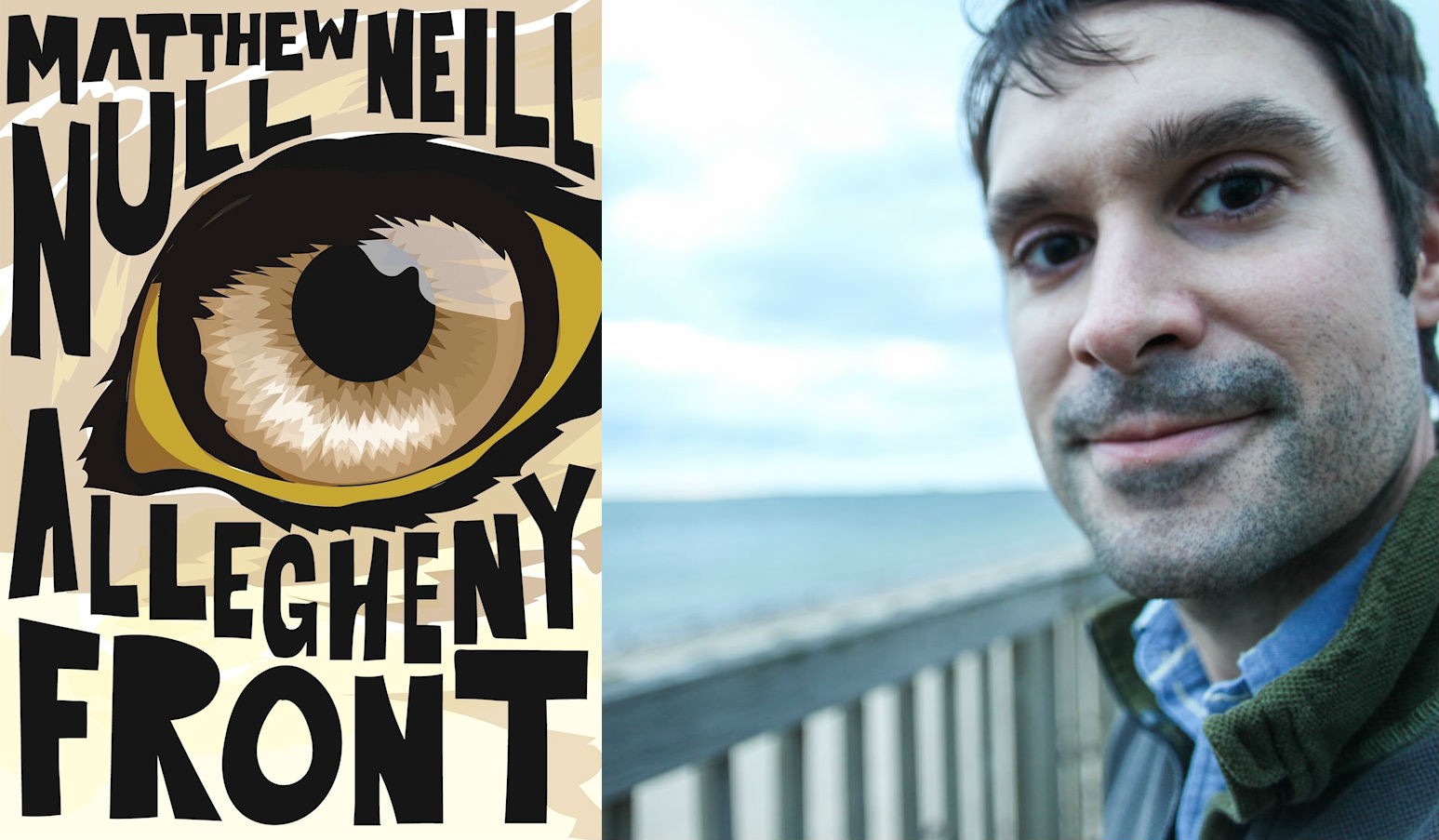

Books & Culture

Hecho En Venezuela: The Private Poetics of Narrative, Memory, and Lies

by Sebastian Castillo

“Every landscape has its card-carrying genius.” — Juan García Madero

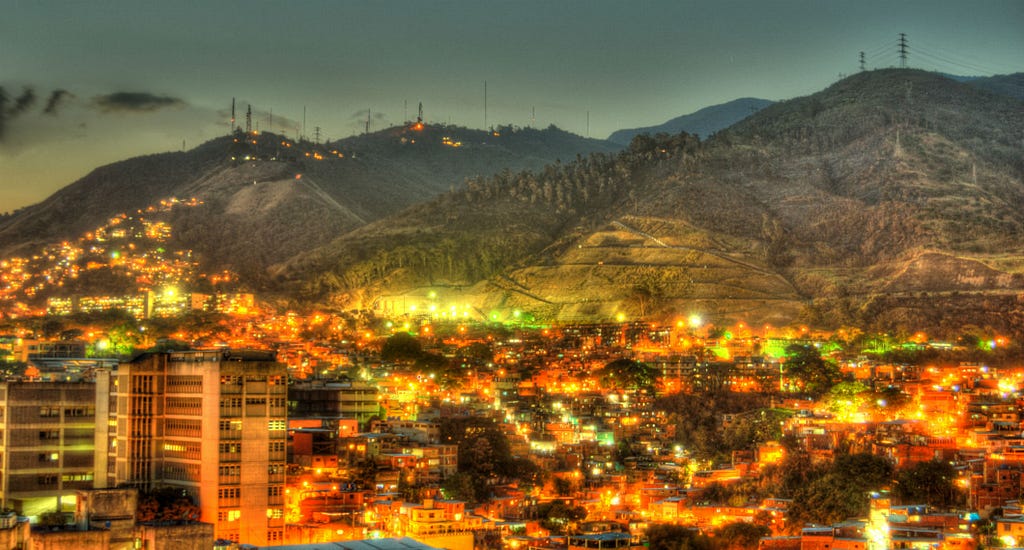

A few years ago, on Twitter, Guillermo Parra wrote, “Venezuela is a continuous goodbye.” Guillermo is a poet, a translator, and a friend. Maybe it’s the kind of offhanded aphorism that invites too much drama — that it portends to a sentimental perspective. But I never allow myself sentimentality, even when I should. I liked Guillermo’s words very much. It spoke to my experience, and to much of my family’s experience, too. Venezuela’s present moment is an erosion of a distant and imaginary country. When I first started writing this, there were tanks rolling down the streets of Caracas, outside of my father’s window. The tanks are gone now, but the situation is as dire as it was then. If our recent conversations are indicative of anything, he’s ready to leave.

Venezuela is a continuous goodbye.

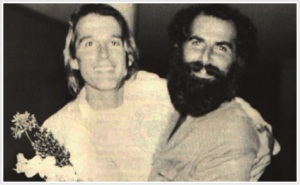

My father’s uncle, Carlos Castillo, is a filmmaker. He’s made low-budget art films on 8mm film for years. A few of them have screened at Cannes, though I’ve never seen any. I’ve found stills on the internet, and the films sound interesting enough, but that kind of second-hand experience doesn’t amount to much. In the summer of 1972, the Austrian filmmaker Hans Müller spent a weekend with Carlos in Caracas. I believe Hans was directly responsible for the few European screenings of my great-uncle’s movies.

Venezuela’s present moment is an erosion of a distant and imaginary country.

I remember Carlos telling me about the first day Hans visited — they were walking down a hot, crowded street in Parque Central, eating ice cream. After exchanging a few nebulous remarks about the political situation in their respective countries, licking droplets of strawberry and chocolate ice cream sliding down their knuckles, Hans asked Carlos, “How do Venezuelan filmmakers approach reality?” Carlos responded: “Hans, this is a crazy country where anything might happen — mattresses could fall from the sky, and no one would bat an eyelash.”

After finishing their ice cream, Carlos and Hans turned the corner down a sleepy side street near the Teresa Carreño Theater, away from the oppressive heat of the sun. It was covered in mattresses. There was an accident; a delivery truck had overturned. A trail of mattresses littered the sidewalk up to the open container of the truck. I assume the truck was delivering them, maybe to a warehouse, or a department store. Hans thought that Carlos had planted the whole scene, like an elaborate set for a film, but he hadn’t.

Carlos Castillo (right) with Diego Rísquez (left). Carlos is holding flowers. Photo taken by Hans Müller.

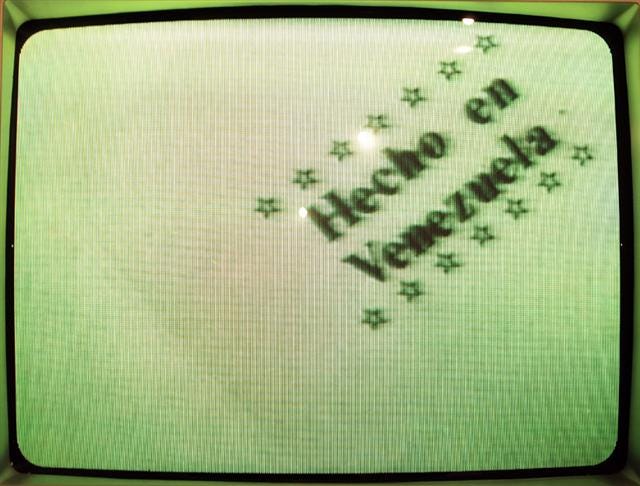

I’m not sure how Carlos met Hans. I’ve asked him a few times and always got different answers. He said that Hans was a friend of Lissette, Carlos’ wife. He also told me that he met Hans in Iran, where Carlos once screened his most successful film, Hecho en Venezuela (1977), which takes place in a garbage dump, though he didn’t explain why Hans was in Iran. Another time, he said that they met on the Paris Metro, where the two struck up a conversation because they were reading the same book, Cortázar’s Hopscotch (1963), in English translation, a language they both spoke poorly. I can’t imagine either of them reading Hopscotch in anything other than their native languages, especially Carlos. They probably met through friends in their field, the most boring and obvious rationale, which is why Carlos didn’t mention it.

My mother used to tell me that a bag of cocaine cost about the same as a cup of coffee, if you can imagine.

Hans’ visit was during one of Venezuela’s last periods of economic prosperity. Even then, most of the country was still very poor, and mired in political corruption. My mother used to tell me that a bag of cocaine cost about the same as a cup of coffee, if you can imagine. Hans was visiting Venezuela for two reasons: he was on his way to Santiago to act in a few scenes for a noir murder-mystery directed by Chile’s most prestigious filmmaker, Raúl Ruiz. Ruiz had asked Hans personally if he would consider playing a small role in the film, because he admired Hans’ work greatly, and thought that Hans had a good face. Hans was staying in Caracas for a few days before filming because he was also doing research for a brief anthology on contemporary Latin American cinema. He wanted to interview Carlos for the book, and a few other filmmakers in Chile and Argentina, including Ruiz, of course.

I don’t know my great-uncle Carlos Castillo very well. In fact, I only have a few vague memories of him, from before I left Caracas for good. I left when I was eight, and while I used to visit in the summers, I haven’t been back in over fifteen years. When I think about my life in Caracas, I feel as if I’m remembering a movie I half-watched at some point in the distant past. I can see angles in the landscape — Mount Ávila presiding over the city in its valley. I can see the food and useless images of the beach. I can see the dirty, hazy city and the super markets that always smelled like raw meat. But it’s more or less indistinct, which to some may sound upsetting, though I don’t think so. I don’t remember my childhood, not really, just like Georges Perec. This gives me the great liberty of inventing much of it.

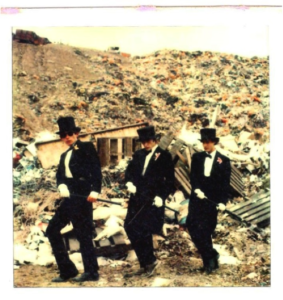

from Hecho en Venezuela. Standing in the garbage dump, blindfolded.

Carlos wanted to introduce Hans to Juan Loyola, a family friend, and a conceptual artist. In his lifetime — he’s dead now, sadly — he’d been arrested for his work and radical politics several times. Carlos thought it would be fun for Hans to participate in Juan’s chatarra project. In Spanish, chatarra usually refers to scrap metal, but it’s a word with a particular connotation in Caracas — a city that’s more like a country, and given as much deserves its own language. For Caraqueños, a chatarra is a rusted, decayed car, abandoned in the streets. Many stay in the same spot for years, if not decades. In the 1970s and 80s, the city was covered in chatarras, most of them in poorer neighborhoods. Juan’s project was simple in conception: he would find a chatarra and re-paint the car in the colors of the Venezuelan flag. He had to work at night, quickly and alone. The police had no problems arresting Loyola, punctuated by a casual beating for his vandalism. But he was essentially painting trash — reframing the public’s unwanted furniture.

The stories I love are usually told by other people. Each person invents a logic of their own when they begin a sentence with, “One day…”

The stories I love are usually told by other people. Each person invents a logic of their own when they begin a sentence with, “One day…” Watching that logic refract and swirl into idiosyncrasy is, for me, the pleasure of the story. The events and their significance are always debatable, if not entirely arbitrary. What matters most is who’s telling you what and for what reason. I won’t make an exception here. I would rather read along, and abandon writing for a moment. Hans was quickly convinced by Juan and Carlos to paint a chatarra during his stay in Caracas. Here it is in Hans Müller’s words, from his essay collection, The Opposing Light: Essays on Films and Filmmakers (1996), only recently translated into English —

Juan Loyola painting a chatarra with a friend. They haven’t yet added the seven stars of the Venezuelan flag.

The day I met Juan Loyola, Carlos took me out to dinner at what looked like an expensive seafood restaurant in Alta Mira, but none of it made sense. It was in the basement of an office building, and while the waiters were dressed in formal attire — almost too formal, maybe, it made me a little uneasy — they all yelled at each other as if they were living through an unending, collective marriage for years. While taking our order, our waiter punched another waiter in the arm for having made a mistake with a drink order earlier in the evening. Thinking it was a bit of aggressive camaraderie, I laughed, but Carlos didn’t. The waiter looked furious and didn’t hide his general animosity from us.

The menus were baffling. The food sounded delicious by description alone, though at the time my sense of Spanish was not as developed as it is today. What struck me as curious, however, were the covers of the menus: they were filled with pictures of disembodied asses on both sides — a collage of asses, all of them cropped at the cusp of the cheek and the small of the back. The various genders of the asses were indistinguishable, though I tried my best to guess while we were waiting to place our order. I remember the restaurant was lit by candlelight only; I could barely see Carlos’ face, even though he was sitting right across from me, smiling or whistling or folding his napkin like a piece of origami.

“Do the menus have something to do with the name of the restaurant?” I asked. We were waiting for our food and already had a few drinks. We started at his apartment.

“No,” Carlos said, “the restaurant is called Restaurante en el Sótano. Restaurant in the basement.”

I laughed. I felt that such literalism either augured very well for the food, or very poorly.

“So why the asses?”

“I don’t know. I think I remember a waiter telling me once that the owner’s son — an artist — won a bet with his father and the result was asses on the menu. Two or three years ago the covers of the menus were just brown leather. Now it’s asses. I think people like it. Either way, I wouldn’t believe whatever the waiters say.”

A man approached our table. It was so dark in the restaurant that I couldn’t see him for a moment. I thought that maybe our waiter had come back to say something disparaging to us. It was Juan. Carlos didn’t tell me he was joining us for dinner. There was a big, idiotic smile plastered on Juan’s face; I though that maybe he was high. I didn’t know if I should take it as a threat or as a welcome. He sat down next to Carlos, and introduced himself.

Carlos had been talking about him all day, so I had to feign ignorance when asking him the usual questions about his life and his work. I was essentially interested in his chatarra project — I thought that it risked the possibility of being too allegorical, that Juan was maybe attached to the easy cache of re-appropriating images of nationalism for protest. But Juan surprised me.

“What I find most interesting about what’s happening with the chatarras,” he said, “is that they only last for about two days or so, at the most three.”

“What do you mean by ‘last’?” I asked.

“The government sends a sanitation crew to tow the chatarras after I paint them. All of them. They erase them.”

I heard a loud smack on the other side of the room — another waiter communicating with his co-workers, maybe. I turned my head to look but it seemed as if no one else in the restaurant was interested, or had even noticed.

“He’s basically doing ecological recovery for our city. By accident,” Carlos said, laughing.

“More or less,” Juan said. “I wish they would let a few of them stay, but I guess that would compromise this unforeseen development.”

I thought it was brilliant. Juan was repurposing the city’s refuse — the government’s casual indifference at the environment of the poor — and instilling it with the specter of a symbol, opaque as it may be. The government in Venezuela essentially found this gesture unacceptable. So unacceptable, in fact, that they provided a service that would not have been granted without Juan’s trespasses… [86–88]

Juan Loyola performing a public reading in 1990. People on the floor and people walking around him.

The rest of Hans’ essay switches from narrative to theory. Carlos, Juan, and Hans paint a chatarra, though it’s an uneventful experience. They find one in Los Chorros, at the end of a dead-end street — close to where Carlos lives now, actually, and about a mile east of Alta Mira. The street is deserted, with the exception of a few listless, stray dogs, and the process goes uninterrupted. Hans sounds a little dejected, as if he wanted to run away from the police, or get into a fight, or experience some kind of simulacrum of art meeting activism in South America — a place many well-intentioned Europeans think of as a magical island filled with bleeding-heart radicals who play out Leftist political fantasies from a safe distance.

Films are particularly effective at achieving this type of narrative rest, because the images are always moving, even when they’re not.

But I shouldn’t let Hans inherit the naïve politics of some of his compatriots: he makes it work, at least in the essay. The story of his weekend in Caracas shifts into a contemplation of Raúl Ruiz’s poetics of cinema, one that’s distinctly opposed to what Ruiz calls the “central conflict theory.” Hans cites Raúl: “A story begins when someone wants something and someone else doesn’t want them to have it. From that point on, through various digressions, all the elements of the story are arranged around this central conflict.” Ruiz’s opposition to this method, one that dominates Hollywood films, is not rooted in a rejection of easy entertainment, or pop consumerism, but in a personal narrative ontology: to understand narrative not as a preoccupation with past or future concerns, but as an anchor to a total present which makes itself available for “an intense feeling of being here and now, in active rest.” Films are particularly effective at achieving this type of narrative rest, because the images are always moving, even when they’re not.

Hans mentions meeting Ruiz a few days later in Santiago, where he tells him the story of his weekend in Caracas. Ruiz suggests that it’s possible that Hans didn’t allow himself to be available to Loyola’s work — the chatarras were already being projected into an imaginary future, where something is always going to happen.

from Hecho en Venezuela. The garbage dump is a place of many endings.

I had my tarot cards read the other day. A friend read them for me. I don’t really believe in those kinds of things, but I was excited nonetheless. Believing in the future is embarrassing enough — I might as well listen to the cards. My last card, the card that’s supposed to tell you what’s to come in the next few months, was the five of swords. It doesn’t bode well. My friend told me that it usually means conflict and isolation — hurting people, pushing them away. It signifies difficult things from your past coming back to affect your future. If it sounds like it could mean anything, I think it’s because it does.

I was telling my father about it when I talked to him on the phone recently. I thought it mostly funny; it didn’t incite anxiety, though maybe I was looking for someone to legitimize my lack of concern.

“You know, it’s funny,” my father said, “I still have this painting that Juan Loyola made for you.”

I remembered it. Or at least, I remembered the memory of the painting, though I couldn’t recall what it looked like.

“It’s of a chatarra. A woman is painting it. It’s kind of dark, a little too gray. But it has your name on it, on the bottom. It says: “Para Sebastian, el futuro del siglo XXI.”

That made me laugh. I told him I was writing a story about Carlos and about Juan and about a few other things. I asked him if he could take a picture of the painting, but he doesn’t own a camera, or a cell phone. He said he would ask his neighbor if he could borrow one, but I’m still waiting for a photo. I told him I wanted to include it in my story. He asked me what else I was writing about.

“Parasitism. I want to write a story that’s parasitic in nature — writing that only exists through other work. It’s called “Hecho en Venezuela,” like Carlos’ movie. I think it makes sense.”

“It does,” he said, “though you don’t always have to make sense.” He paused. “What time is it there?”

What I find more interesting is that a person effectively changed the time for an entire country.

We had been talking for an hour and both lost track of time. He had to go to a friend’s party; I did, too. It was 8:45 in Philadelphia, so that meant that it was 9:15 in Caracas. In 2007, Chávez reestablished the meridian that was used in Venezuela between 1912 and 1967, setting their clocks back half an hour. There were several reasons provided for the decision, for example, that it helped farmers in the far west of Venezuela, so that they didn’t have to wake up as early in the morning. Many took it as a symbol of Chávez’s megalomania. I don’t really have an opinion either way. What I find more interesting is that a person effectively changed the time for an entire country. People who existed in one time were, one day, permanently moved to another.

One of my favorite films, Tsai Ming-Ling’s What Time Is It There? (2001) is about a street vendor who sells watches in Taipei. He meets a young woman who’s moving to Paris in the next week, so the vendor sells her a watch before she goes. He doesn’t know her very well, but he forges a connection with her nonetheless, or maybe simply an obsession. The film exists in a narrative present, like Ruiz’s films, that doesn’t reveal the psychological conditions of its characters in a way that allows for closure, or even intelligibility. In fact, the street vendor never sees the woman again after she leaves. He watches François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) on repeat, perhaps as a way of maintaining a connection to the woman’s new life in France. Watching the film is a way through which the street vendor creates a living connection in disparate temporalities — however delusional it may be.

What I love about the film is that it frequently presents long, static takes of the street vendor at home, alone and in his pajamas, watching the Truffaut movie. We are effectively watching him watch the film. The 400 Blows, as you may know, is about a young boy attempting to make sense of the neglect and emotional apathy of the authority figures in his life. In the last scene — the movie’s most famous — he wanders the beach, dispossessed and uncertain of his future. The camera freezes on a close-up of his face, where he permanently lives. In What Time Is It There?, the street vendor’s gaze reflects a kind of permanence of its own. He watches the movie in a present that’s endlessly eroding, one that provides him an anchor to a different time, but which also functions as a closed gate between his time and another. Like the old man in Kafka’s “Before the Law,” he sits outside, waiting for the moment of entry.

I read Álvaro Enrigue’s Sudden Death (2016) a few weeks ago. It’s a stunning novel interspersed with obscure historical research, absurd fictions about its central personages (which include Caravaggio, Quevedo, and Galileo, among others), intricate structural play, and a lightness in Enrigue’s prose which makes it a total delight from beginning to end. Two-thirds through, the narrator — maybe you could even say Álvaro himself — interrupts the novel to tell the reader: “I don’t know what this book is about.” The admission is startling. I felt that I had never read something so generous in a novel. It reminded me of one of Enrigue’s earlier short stories, “On the Death of the Author,” where he concludes with the following: “Sometimes writing is a job: to obliquely trace the path of certain ideas that seem essential to put on the table. But other times, it’s to grant what’s left, to accept the museum and contemplate the sum while waiting for death…To put our little boxes on the table and know that what ended was also an entire universe.”

Two-thirds through, the narrator — maybe you could even say Álvaro himself — interrupts the novel to tell the reader: “I don’t know what this book is about.”

When I first started working on this, I wanted to write an essay that was filled with lies, one which placed the source of its affect (which is always a burden) elsewhere. The truth is that given its intent, its lack of narrative fixity, and its subject matter, a true ending is impossible. Or maybe I’m simply allowed to end wherever I place the final period, which is what always happens anyway. If I finish with any faith (which I’m allergic to), it’s that perhaps Ruiz, or Carlos, or Müller, or Loyola would accept this baggy museum. Maybe one day this will be a book. That way, I can forestall my punctuation a little while longer, for an imaginary future, where something is always going to happen.

— Philadelphia, October 2014 — May 2016