Interviews

Stephanie Danler on the Restaurant Industry, Life Experience, and Choreographing a Novel

by Megan Cummins

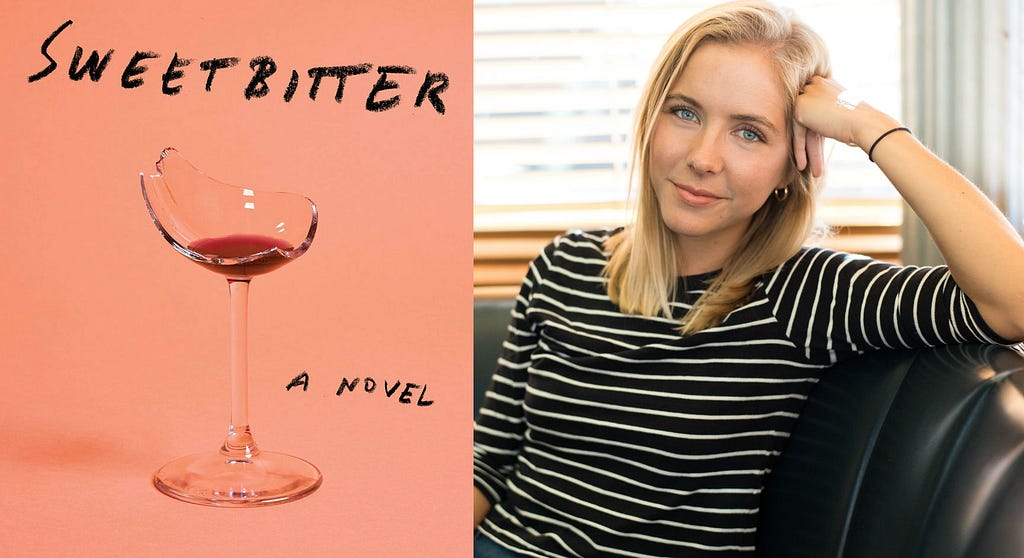

Sweetbitter (Knopf, 2016) is a profoundly sensorial novel by debut writer Stephanie Danler, in which the protagonist Tess — who is young and fierce, optimistic and hungry for experience — works as a backwaiter at a restaurant near Union Square. “You will develop a palate” is the book’s opening line, and from there Tess embarks on a luscious education on food, wine, sex and love. Central to this experience are Simone and Jake — a senior waiter and a bartender, respectively, cynics, both of them, who have a complicated history and who are seductive forces for Tess.

A former restaurant professional and incredibly talented writer of emotion and metaphor, Danler has written a book informed by her own deep knowledge of the restaurant industry. As Tess develops her palate — the central metaphor of the book — I fell under the spell of the book’s construction, through which one experiences the hectic and exhilarating nature of working in a restaurant and the gravity of food as story, thread, and history.

I met with Danler for coffee at Via Carota, one of Jody Williams’ restaurants in the West Village. We talked about New York, the choreography of restaurants, the structure of novels, and developing a palate that stays with you forever.

Megan Cummins: Sweetbitter opens with Tess, our narrator and protagonist, trying to get across the George Washington Bridge, but she doesn’t know about the tolls. I grew up in Michigan where there are no toll roads so I didn’t know about them either. I love that she gets turned away and she has to go to the Dunkin’ Donuts off the turnpike where she gets mistaken as a regular — and let’s face it, no one wants to be a regular at the Dunkin’ Donuts off the New Jersey turnpike.

Stephanie Danler: I’m so glad you got that. I was like, what is something terrible that could happen to her in this Dunkin’ Donuts?

MC: And getting recognized is exactly it. Because she’s so close, right? And she worries she’ll have to go all the way back to Ohio. But then she gets back to the toll both and she says, “Can I get in now?” And so that made me think of New York as this place that has borders and has a certain exclusivity to it — but also once you get in, it feels endless in a way. But you have to get in first. So I was wondering if you could talk about New York as a place that feels both exclusive and endless?

SD: A private club. Of course. I think that New York is this bubble and feels impenetrable for a lot of people that are not living in it. I think it takes a certain kind of person who has to be a little bit dumb and a little bit brave — and those two often go hand in hand — and also kind of ambitious, that comes here. There’s also some fearlessness involved. It’s so different from any other place in the United States, with its own customs and language. The people look different. It has its own grid. The maps look different. It has its own system of transportation. It is literally alien to 99% of the rest of the country. And so I think you find a long literary tradition of people coming to New York who have that drive and ambition and the desire for reinvention and the desire to penetrate the bubble. That penetration involves becoming themselves or becoming something. That is what every New York story that is close to me is about. The toll both is interesting because I kind of saw that Tess had these three points of entry early in the novel. They were the toll both, the bar where she has to get the keys to her apartment, and passing the test with Howard [the general manager of the restaurant]. And it’s not that she is in after that, and everything’s easy, but she’s allowed to play the game. She has been allowed to start. That’s really where the story takes off. From there it’s a series, to me, of initiation rituals like anything else, like any other private club or the military, where they take away your name, they take away your clothes. You don’t talk. You just learn and absorb the rules and language of this new world. And then when you emerge sixty pages later, or whatever it is, you’re a new person. And it’s interesting that you brought up that line — can I get in? — because that is really important. When I was writing this, my editor or classmates or teachers would ask, what’s the transition she’s going through? I think in fiction there’s this idea that there needs to be some transition. I made it from Point A to Point B, here was my trajectory, and Point B is so different from Point A. Here was my epiphany.

MC: Right — in the middle was my turning point.

SD: Exactly. It’s not even that it’s a formula. It’s how readers connect to the story. But I was really resistant because I wanted her journey to be a series of very subtle transitions because I think that’s how real growth happens. So that can I get in? changes when she’s walking across the Williamsburg Bridge at the end of the book. It shifts to it was my city when she realizes she didn’t need to ask for permission from anyone. And this whole process is her taking ownership of the city, and going from can I get in? to I’m here, this is mine.

MC: Taking ownership strikes a chord with me. Throughout the book everyone is asking her what else she does. What else do you do? And I feel sometimes that people in New York — or maybe everywhere — people are expected to be doing a hundred different creative spectacular things all while making a living. I was wondering what about both being young and being in New York makes Tess the subject of that question, What else do you do?

SD: It’s interesting that you say it’s about being in New York and the expectation that you’re managing five different lives simultaneously. I think in Tess’s case the expectation comes from an old stigma about the restaurant industry that has changed since the food culture explosion. The novel is set ten years ago. The food scene was already in the beginning stages of blossoming but since then we’ve seen it erupt. By seen I mean the industry as a viable job with growth that’s attracting highly educated, creative people, who aren’t just using it as a temporary stopgap before they go on to their real lives. I personally have been working in restaurants since I was fifteen, so for sixteen years when I stopped waiting tables, and there was always this stigma about this job as being throwaway. What I realized when I got to New York is that even the busboys were professional busboys. They knew their jobs inside and out. And it goes with this cliché that to live in New York you have to be the best at what you do. And these servers are the best at what they do. And a Danny Meyer restaurant, which is where I had my first job, attracts those kinds of people. I was blown away by it. I remember at that point in my life when people would ask me what else I was doing I would say, “Oh, I’m a writer.” But not everyone around me was. They were servers. They were career servers. And they were still pursuing their hobbies outside of their job, but they didn’t feel that same defensiveness. I think that for Tess, she’s so enamored with the world, it fills up her landscape so completely that she’s forgotten that she should be able to answer that question. I think that’s just very accurate of what I saw. And there was a time after my first couple years in New York that I stopped saying that I was a writer. Because I wasn’t. I was a restaurant professional. I was a sommelier; I went to wine school; I managed businesses; I helped open businesses. I was pursuing life in the restaurant industry, and I didn’t need to justify it with anything else. But initially in 2006 I think there was still that urge.

MC: Absolutely. And I also am thinking of a part from your book relatively early on when Tess almost opens the door to the coffee shop on Bedford Avenue to ask for a job but something tells her not to. And at the end of the book I thought about that moment again because I think something about the setting of the restaurant felt so perfect for a novel.

SD: Me too, obviously. [Laughs]

MC: You describe so well the very precise choreography of working at a restaurant, which Tess masters, and it made me think that you have to have a sort of similar, very precise choreography when writing a novel. So I was wondering why you were drawn to writing a novel rather than say a story? And I was wondering if you saw any parallels between the structure of working at a restaurant and the structure or balance of novel writing.

SD: Yes. There are two questions in what you just said. Why a novel, why not a story for this? And then there’s something about structure and form.

MC: I clung to the very precise choreography of the restaurant. When one thing goes wrong the whole service dissolves. And I think that can be true of a novel too.

SD: Absolutely. I was really interested in the form of the novel as mirroring the content exactly. And so you say choreography, and I’m thinking of rhythm, as far as the way the vignettes are set up, the speed with which the story unfolds, the speed of certain sentences versus the slowness of some other scenes, and I was very aware of balancing that the entire time. But all in an effort to make it feel like working a dinner service.

I wanted the experience of reading to be as close to the kind of dance of dinner service as possible

I wanted the experience of reading to be as close to the kind of dance of dinner service as possible. I’m so happy you said choreography because I paid so much attention to movement. So much of the book is Tess watching how other people are moving and trying to learn how to move the same way. I think consciously and unconsciously that falls away toward the end of the book because the job has become automatic to her, which also mirrors the real life experience of first starting a job and paying attention to every tic, where everyone’s eyes are landing, how people come from around the bar, how people are holding their plates, where people are positioned, and then it becomes second nature at a certain point and she can move on to the emotional intricacies that are bubbling all along the surface. But I agree that there’s something in the choreography of a dinner service that lends itself to writing a novel, if only in the fact that you are juggling sixteen different emergencies simultaneously and needing to hold them all in your mind at the same time. One of the more difficult things about novel writing that I found — because I’d never done this before — was being able to hold the end of the book in my mind while I was writing page seventy and knowing that they were all interconnected, and no decision was isolated. Nothing was isolated within the story. When I was editing it I would think, I need to do something on page twenty-five. You would think I could go to page twenty-five and make an adjustment. And I found my process to be horribly inefficient, but I needed to write up to that scene, and write away from that scene, in order to make any change, because of how interconnected everything was.

MC: Like if you drop the plate on the floor, you can’t just pick it up and put it on the table. You have to start over.

SD: Totally.

MC: The book is so metaphorically rich.

SD: It is a metaphor. It’s a metaphor about a palate, and developing a palate. The entire arc of the story is in the first sentence.

MC: You pull it off so seamlessly. The metaphor is carried throughout and yet it’s a real moving fully-fledged story of this young woman discovering her palate and her body in more ways than one. One thing that struck me was just how beautiful the descriptions of food are and how important food is — clearly it’s at the center, the restaurant is the food. I was wondering what your relationship with food was as you were writing the book. Did food and wine like the food and wine in the book fuel the language as you were working on the book, or was it all from memory?

SD: I was a food professional from 2002–2009 and then I went to graduate school and I continued waiting tables. And then I had already been changed as a person. This transformation Tess goes through where she learns to pay attention to the world through food and wine had already become my life. I was surrounded by incredible cooks, I’d been traveling to every wine region in Spain with my bosses for five years, multiple times a year. I’d been going to France. My life had been eating. On my days off my ex-husband and I would eat at three different places in a day because we only had one day off and we wanted to try everything in the city, and we’d go to Flushing to Chinatown there. So I already had that obsessive knowledge. But by the time I was writing the novel and in graduate school and working nonstop it wasn’t my life anymore. I loved being around food and I chose [to work at] Buvette because it’s one of my favorite restaurants in the city. I cherish being around Jody’s food. But it was also the only kind of job I’d ever had. And I knew it could give me the life that I wanted and I could support myself while I was writing. So a lot of it was from memory. A lot of it was trying to remember what it felt like to be fully inundated and cosseted in this industry. At this point I was learning about the publishing industry and learning about being a graduate student. And my whole life had changed. Every single aspect of it. People have asked me whether I had to research the book. And it wasn’t that I had to research, but I had to re-access something I wasn’t living in the moment anymore. And I was lucky that I remembered, and that I stayed close to wine. Because I had worked in wine retail more recently than I had in restaurants. Definitely. It was far away at that point. And being twenty-two was far away at that point. That was hard to access as well.

MC: Yeah. In some ways I feel like twenty-two, perhaps for our generation, is the first year of being an adult.

SD: Yeah, that’s why I chose it.

MC: Not for everyone, but in many cases. So it’s a perfect age for Tess, I think.

SD: There’s something about this prolonged adolescence through our twenties that so many writers and filmmakers have tapped into. But I do think that when you’re twenty-two, especially if you move to New York around that time, you’re not protected by your parents or the town you grew up in or your continuous identity from people that have known you. You’re not protected by an institution. There’s no school and academic calendar. There’s this brand new autonomy and a lot of twenty-two year olds that I see in New York — because after I was one I managed them for years — are drunk on that power. And so that part of Tess’s giddiness is something I could recall from myself but also observed over and over again hiring people in restaurants that were just getting here. And free.

MC: The back-story for Tess is relatively spare in the book.

SD: It’s very spare!

MC: We know enough and we know it’s good she got out. That she had to flee in a way. Her mother left when she was very young. Her father seems very distant. I was wondering if you could talk about that decision to exclude a lot of Tess’s family history.

SD: It was really such a natural choice and of course one that throughout graduate school a million people told me would never work and I was determined for it to work. I knew that it worked for the story that I wanted to tell because Tess is a present tense creature. I wrote her to be new. To be blank in a certain way so that her impressions of the world could be heightened and so we could feel everything through her fingertips as she touches it for the first time. It was a very delicate balance because a real blank slate is not a character and it’s certainly not a protagonist. So she needed to have weight from the very beginning, and a lot of weight comes from voice, I find, in fiction. It comes from the ring of authenticity of the voice. We know enough to know that she’s had some damage, we know that she’s escaped, we know that she’s observant, sensitive, ambitious, innocent. We know that in order to make the decision to move here I think you have to be inherently optimistic which is something that comes out throughout the book as she realizes I am different from these people who are nihilistic. I’m actually an optimist. Which is what saves her. So nothing else was necessary. The other aspect of that that I wanted to capture in the book is sort of the claustrophobic nature of living in New York and working in a restaurant where there’s really no context outside. New York experience is the only thing that counts — they tell her that — but you find that’s true in every single industry across the board. People want to know where else you’ve worked in New York as though you didn’t exist before you got here. A lot of your prior experience isn’t translatable because this is such an idiosyncratic place and so by keeping her within that bubble it felt more true to the experience of living here.

MC: I’m so glad you brought up optimism because I definitely saw Tess as an optimist. And her optimism sort of runs up against the cynicism of the other characters. Particularly Simone and Jake. And of course with Jake, I was seduced by him too. He’s just this beautiful bad news.

SD: He’s a nightmare.

MC: Such a nightmare. And so I was wondering…there are so many parts where I could see her attraction to Jake, and especially thinking back to how a twenty-two year old would be so compelled by someone like Jake. I saw him too as just being so careless with her. Tess is the youngest and she’s an optimist, but in general many people in the restaurant aren’t very careful with each other, so I’m wondering what about that age makes people not be careful with each other?

SD: So Jake’s thirty. Simone’s thirty-eight. I think that there’s something about overstaying your welcome, especially in the restaurant industry, people staying too long at the party, and it creates toxicity. And the toxicity comes from boredom. This is enchanting and enthralling to a twenty-two year old over the ten months — I think we get to eleven months — that we’re with her. For twenty years I think it’s probably stifling. I know that it has stifled Simone’s ambitions. And Jake is at the cusp where it’s about to stifle his. Tess for him is his last chance in a way. Or the closest he’s come to being able to break out of this disillusionment.

This is a disillusionment coming-of-age-story

And you have the old world disillusioned cynical characters but Tess reminds Jake that he doesn’t have to be that way. That’s his attraction to her. But at thirty, having been there seven years and having been Simone’s collateral damage for his entire life, he has the smallest amount of hope which is what Tess taps into. And not every day, because I didn’t want to make a fairy tale out of this. He’s an asshole. He’s an emotionally stunted asshole who can’t give her what she needs. But I think in the experiences that I’ve had with those kinds of men, and that my friends have had, there are these moments of softness and lucidity, and those are what keep you going for so long. And Tess definitely has that with Jake, especially toward the end. But I do think that a lot of broken dreams, stifled ambition, all of this can create a cloud, that Tess isn’t aware of when she first gets there, of bitterness. And you see that in the restaurant even though it is such an incredible job and it gives you an incredible life, anyone who stays too long anywhere finds that they lost their way and risks bitterness.

MC: I thought the struggle with Jake was expressed perfectly when he and Simone surprise Tess with a birthday cake. Tess is talking about traveling, and Jake comes up behind her and says, “Where do you think you’re going?” in a very affectionate way and at the same time is planning a trip to Europe without telling her.

SD: He doesn’t even know. Tess registers so little [to him] in a way when she’s next to Simone. I remember discussing that with my editors, whether Jake registers a betrayal, and I said no. He doesn’t. He registers that she’s upset and that he’s hurt her feelings but I think he’s too far gone down his path. It’s the worst.

MC: I felt the betrayal so strongly. And it’s interesting that you describe Jake as Simone’s collateral damage. Family is such a big theme in the restaurant. The whole restaurant is a family. They have family meal. But then Jake and Simone and Tess as well have a small family within that family. In some ways it’s edifying and nurturing, and Tess learns so much from Simone, but as you said Simone has already crossed into the realm of bitterness. That just made me think about family. I was wondering if in the book being in a family is emotionally perilous?

SD: My personal beliefs might differ from what I put into the novel. New York City attracts these orphan types and I have always thought of Tess as an orphan. Even if you’re not an actual orphan most of us here are cut off in a way from our families. Everyone came from someplace else for the most part. I think that your natural inclination is to recreate that security as quickly as possible and for someone who’s never had it, like Tess, to fall into a restaurant, where there’s family meal and everyone feels they’ve been born there and they’ve been there a million years, and then for her to be attracted to Jake and Simone who have this strange mother/son, brother/sister underlying bond of actual family, that makes sense to me. The way she latches on to Simone is very connected to her having never had a mother. I do not think that for Tess family is perilous. I think being so unformed and not knowing herself — and this might be true with family as well — I think being at the mercy of the people you love is perilous. And so if part of her journey is taking ownership of her city, I would also say part of her journey is developing boundaries, even boundaries as simple as I don’t like that. I think that’s what puts her in a position to fight back against Simone and Jake toward the end. I think that I’ve had a lot of experience with toxic families, and through my friends incredible experiences with great families, but I do think that losing your individual identity within that family is very dangerous.

MC: Interesting. You answered my question in a much more nuanced way than I phrased the question. What you said about how it’s not family that’s perilous but it’s about not being fully formed — that’s what’s perilous.

SD: It’s really dangerous to give yourself over to other people. Of course that’s the thrill of intimacy. But when I was writing the book, something I was obsessed with was how we don’t know each other, how we get into these professional environments. I’ve worked with so many people over the years, and I know these tidbits about them, and in the moment our intimacy was so intense and military-like, just like being in the trenches with someone, and when I left I knew nothing about them, sometimes not even where they were from and we had shared so many evenings together. And I think that where Tess is really reckless isn’t with the drinking or the drugs, but it’s with giving herself so freely to people.

MC: Yes. She’s very thoughtful and she’s very curious and she’s very genuine and earnest whereas everyone around her is —

SD: Not saying what they mean.

MC: Exactly. And she believes them because she means what she says. And that to me was so much the heart of Tess’s journey throughout the book. And the drugs and the drinking, they’re both substances for the body. They’re two parts of her life that in a way revolve around the restaurant and they’re both things that fuel her. Are the drugs for her working in concert with the food, or are they separate?

SD: I think that cocaine is a drug, food is a drug, wine is a drug, sex is a drug. Xanax is a drug. So what we mean by drug is that they put her into a heightened state. They give her a rush that she becomes addicted to. And she has the realization several times that she’s gotten into a lifestyle of more. I want more flavor, I want more feeling, I want more hours in the night. And so I don’t think the substance matters. I think that what she’s exploring throughout the book is an appetite. And that appetite is for life and for experience. And so food and drugs are absolutely on the same level. But determining what’s good for me and what’s bad for me is something I’m still negotiating at thirty-two, but that’s a big part of growing up and coming of age. Initially, especially when you’re quite young and you haven’t fully understood consequences yet, or maybe you haven’t had enough autonomy to understand them, there is no distinction between good and bad. It’s all just new.

MC: It’s part of her palate too. The night she blacks out, when she gets out of the car she says she takes a bump of some really good shit, and I had this feeling that at the beginning of the book she might not have been able to register what was good quality and what was bad quality.

SD: Yeah. Absolutely.

MC: At times in the book Tess is depressed, or maybe just sort of sad in the way young people are sometimes sad.

SD: Young people? Everyone!

MC: Right! Of course! Sadness doesn’t end when you’re not young anymore. I wrote down a quote here, something Tess thinks: “Sometimes my sadness felt so deep it must have been inherited.” That made me think about how food in the book is something with a history, a thread, a story. And then there was the dinner service with the seafood towers. There were only seventeen seafood towers to sell and they were gorgeously constructed, $175 each, and something about them made me so sad for some reason. These beautiful things that were so fleeting. I think food for Tess is an ecstatic experience, but is it also ever a sad experience for her?

SD: Of course. And you talking about that makes me think how so much of the sadness for Tess is that these things aren’t permanent. Her highs aren’t permanent. Her relationships with Jake and Simone and her coworkers aren’t permanent.

Food is a very intense but transient, fleeting, ephemeral experience that is erased at the end of the night

Food is a very intense but transient, fleeting, ephemeral experience that is erased at the end of the night. I think mentally that’s really hard on you when you’re working in restaurants. I think — and I say I think because I worked in restaurants for so long and I don’t really know another way of life — but there’s something about a job, an actual profession, where there’s no accumulation, where you don’t make lists that carry over from day to day, where you never complete projects, you complete evenings, and you could have had a great night and the next day you’re starting over from zero again, and I think it’s a hard space existentially to live in. To recreate this experience every single day. I also think there’s something about sex that is also a temporary intimacy that she’s struggling with, and trying to extend, and that’s what she’s beginning to figure out — first that sex can be intimate, and she’s trying to see if she can spread that out over her entire life, and she can’t. After eating an incredible meal, after consuming this seafood tower. I think about this all the time because I’ve spent such ridiculous sums of money on food. For my 27th birthday, my ex and I saved up and went to Per Se and it cost as much as our rent. It was really important to us. But it was six hours and that was it. It was over. I don’t have anything left of it but these memories. There’s no accumulation. It’s all ephemera. And it is sad, but also the way of life. And what that produces for Tess is a heightened awareness of beauty when she has it. I don’t know if she fully gets there within the novel but I think that accepting how temporary it all is often gives you those highs and those lows.

MC: Throughout the book people are telling Tess, “It’s just dinner.” Or Simone is saying, “Don’t worry little one, none of this will leave a scratch.” But by the end Tess is saying no, the point is that there are scratches.

SD: Everyone wants to brush it off, the experience. The entire novel, because she’s young, everyone is telling her that what she says doesn’t matter. That what she thinks is important or permanent is not going to be. I find myself talking to young people like that now, discounting what they say as “You don’t know what you’re talking about yet.” They haven’t lived enough. But their observations and experiences of the world are still valid and so precious. And I remember feeling that when I was young. I wanted to tell people older than me that were disillusioned that they were wrong. That they just weren’t in touch with that part of themselves anymore that could feel the way I could feel. So that is Tess’s very sincere genuine struggle with Jake and Simone. I think that her realization at the end that she is marked is kind of fighting back against that fleetingness, that knowledge that this experience is something she’ll never have back. The permanent part is that the way she experiences the world has been changed. She’s developed a palate. That never changes, for the rest of her life.