Craft

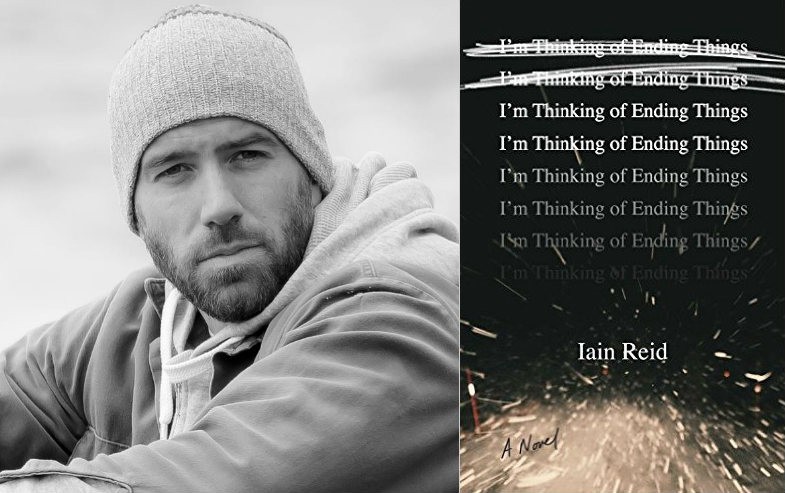

Iain Reid On Switching Genres, Loneliness, And Writing as a Culinary Reduction

by Ann Cinzar

To meet Iain Reid in person is to wonder how such a dark, suspenseful, and genre bending novel could be written by such a charming guy. Reid’s debut novel I’m Thinking of Ending Things (Simon and Schuster, 2016) takes the reader on a frightening road trip with a couple trying to determine the fate of their relationship, while nimbly exploring bigger themes of marriage, identity and solitude. This work is a stark departure from his two previous critically acclaimed memoirs. I spoke with Iain Reid about the move to fiction, finding a balance between wanting to be alone and being lonely, and the quest to find the answers.

Ann Cinzar: After writing two funny, light, entertaining memoirs, you’ve now moved to fiction. But, apart from that, you’ve also written something which in many ways defies categorization. Did you set out to write a book that would be totally different, one that might not fit a specific genre, or did it evolve?

Iain Reid: A little bit of both I think. I wanted for my own sake to do something that was different and that was for me exciting and interesting. As a reader I enjoy books and novels that make me feel a little unsettled, and not just in the content. I like that feeling as I’m reading something that I’ve never read anything quite like it. I’m not sure what I would describe the book as, or where it would fit in the bookstore. So that was in my mind, but not actively as I was writing, because by then you become obsessed with the story. But it came into my mind early on that I wanted to write something distinct and knew it would probably frustrate some people as it’s hard to classify or fit into any specific genre. I did think that would make it harder for a publisher to commit to releasing this book, because it’s a risk. There was no guarantee when I wrote it that someone would published it. I feel lucky that it found the editors who believed in it and got the chance to help and work on it. I think where it ended up turned out be the best place for it.

Cinzar: If you had to categorize it, what would you call it?

Reid: I would call it a novel, which I guess is vague. I would call it a story. It has elements of certain types of genre books but I don’t put it in any of those. Some people will, and that’s fine with me. There have been people calling it a philosophical thriller, and that isn’t a genre but that sounds right to me. I was more comfortable with that than some other things.

Cinzar: Maybe it’s a whole new genre?

Reid: That’s not up for me to say. That’s up for people who read it and they can decide. I’m just as interested as anybody else to hear what people will say, and what they make of it, or if people even read it. But I’m comfortable calling it a novel.

Cinzar: Your first two works of non-fiction, both memoirs, were well received and critically acclaimed. Why not stick with that genre and write another?

Reid: I think partially it’s because I’d written two books of non-fiction that are similar in tone and style. They’re about pleasant experiences in my own life and about real people in my life. Also, the process of writing them was comparable. So for my own sake I wanted to do something very different. First of all, that meant writing fiction, and second it meant new content. If I was going to think about something for a few years I wanted it to be unexplored and interesting for me. I remember meeting my agent for lunch right around the time my second book was set to come out and she asked what are you thinking for your next project? And that’s when I said ‘I have this idea for this story. It’s pretty disturbing and it’s a novel’ and she right away encouraged me to keep going. That’s when I committed it to it fully. Maybe if she had dissuaded me and said ‘I think you should write another memoir or non-fiction first’ I would have put it on the back burner but I think getting her early encouragement made me go into it full force.

Cinzar: Early reviews have compared I’m Thinking of Ending Things to everything from Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin to Michel Faber’s Under The Skin to The Shining — -or maybe it’s just me comparing it to The Shining. Were there any specific influences as you were writing this book?

Reid: Definitely. I don’t know if I would be able to untangle everything and identify each specifically, because there wasn’t only one book or movie that I had in my mind when I was writing it. But all these books that were relevant to this story were in my mind. All those you mentioned, I wasn’t directly thinking about any of them, but they all have a place, as far as being influenced by them. I’d say even some movies, like Hitchcock. And Music. In particular, the band METZ — both of their records are ones that I listened to a lot while I was writing the book. METZ’s music captures a certain type of feeling and this book shares similarities to what that music evokes and conveys. A lot of times while I was stuck I’d go out for a walk and listen to that music and they go well together. And other music too. I often find music can have that effect and can influence and shape the way you write. But definitely any book that has rattled me would have in some way influenced the writing of the book. I can’t say one more than another — -It wasn’t an homage to any one book or author or music but it comes together in a way that is beyond your control. It happens on a level somewhere that is basically hidden but you know it has an effect.

Cinzar: It’s funny you mention music because as I read the book there were a few times when I thought “What is with the country music?”

Reid: Again, I think music is relevant to the story. We often listen to songs we like over and over again, and music is very evocative and brings us back to certain places and time, or messes with our sense of time, and it was relevant to the story.

Cinzar: It’s not giving anything away to say that the book begins with Jake and his girlfriend starting off on a road trip together. I love how within the first few pages, as they begin to drive into the country, Jake’s girlfriend comments that it must get really dark out there where they’re driving. And Jake replies, simply, “It does.” To me that line sets up the whole story you’ve written, which is so dark and ominous. After writing two light, funny books, how did it feel to write something so dark?

Reid: Darkness comes up in the story, in a few spots, even when they talk about space. So that is a theme in the book. But writing something that was dark was part of this progression as a writer. The two things I wrote previously were meant to comfort people, make them laugh, warm them. I don’t know too many writers who want to continue doing the same thing. You want to challenge yourself and do something that’s difficult. So I had done one thing and this novel was different. So it does have elements that are quite dark. But It’s not entirely dark for me.

Cinzar: Really? Which parts aren’t dark?

Reid :(Laughs) Some readers might disagree. For me, ultimately the book is about people and the people in our lives, friends, family, etc., and how important those relationships are and how easy it is to take them for granted. And that’s something I was thinking about a lot while I wrote and keeps it from being a totally dark book. That reflection on others in our life provides meaning for everybody. You can’t exist entirely on your own or in solitude. As someone who believes in solitude, it has a limit.

As someone who believes in solitude, it has a limit.

I was thinking about a lot of the people in my life who bring meaning to it and that counters some of the darker elements of the story.

Cinzar: Definitely that theme of relationships, as well as other themes and ideas like marriage, identity, and loneliness recur throughout the novel. Yet you’ve explored them in what might be considered a suspense/psychological thriller/horror story. What was the impulse to use this unlikely vehicle for those themes?

Reid: I think that’s what is was. If you wanted to write an essay or long non-fiction book on these themes it would probably be less fun to read. It would be dry and no one would want to read it. I thought I could think about these larger ideas and themes and incorporate them into a suspenseful story, which to me seemed natural anyway, because I find some of these themes unsettling. But, I also thought it might draw more people to the book. Some people may come to this book and they’ll just get the hit of dopamine when you read something suspenseful and that will be enough for them, and they won’t even realize they’re ingesting the other stuff. But I thought this type of story and the pace fit the ideas and the content nicely. In my mind this was going to be a story that was uncomfortable. For some people at least. I’m curious because I think this book will garner a wide variety of reaction so that’s interesting to me.

Cinzar: I’m Thinking of Ending Things is a relatively short and tightly written book. Was that a conscious decision?

Reid: Oh yeah, that was in my mind right from the start. And it became a priority particularly as I was finishing the first few drafts, even before getting into some of the big edits with the editors. I probably removed as much of the book as what stayed in. The book could have been twice as long but I knew that I wanted it to be as concise and short as possible. And that can be hard because sometimes you work on something maybe for a few months and it could be a chunk of the story, and you like it and it works technically, but you realize it doesn’t need to be in there, it doesn’t progress the story, so you have to delete it.

Cinzar: That’s a good lesson for writers.

Reid: Yes, it’s like liposuction. There were months of that. Removing stuff that took a long time to write, but you had to go in and clean it out. For this story it needed be that way. There are long books that I love that provide their own kind of pleasure. But I thought of this, to use a food analogy, like a reduction, something that you boil down, and then you have a spoonful of it and it has its own flavor. A full thanksgiving feast is something else, and that’s also great, but this you give on a spoon and you hope it still provides a certain enjoyment. But it was definitely in my mind to keep it that way. Hopefully all the stuff they talked about in the car is still in your mind by the time you get to the end. I know people are busy so I wanted them to feel maybe they could read it in one or two sittings. I think that way you’ll get the most out of it.

Cinzar: Let’s talk a bit more about this idea of solitude, because that theme of being alone and loneliness runs throughout the book. And it’s not only the question of can we be alone or are we meant to be alone, but that question of “are we alone?’ It reminds me of that scene from the Sopranos where Tony’s mom is dying and she tells him, “Anthony, don’t expect happiness…in the end you die in your own arms.” Do you think that’s true? In the end, are we all just alone?

Reid: Well, that’s a good question. That’s a heavy, important question to think about and I don’t think there is one right or wrong answer. You could talk about it for hours or days and never fully reach a satisfying conclusion. The only thing you can do is consider more questions. And that’s a lot of what this book is about: finding things to discuss and creating a dialogue to work through things. That’s how the story starts. Jake’s girlfriend is trying to figure out things about her own life and this relationship and whether she should continue or not, and she falls into this pattern of the philosophical dialogue to get through it without even realizing she’s doing it. So the question, are we just alone, I think there are multiple ways to look at it. I would answer yes and no. I’m not trying to be evasive but I think that’s the truth. I would say as a human being we require others. We’re seeing it more…even with restrictions on solitary confinement in prisons. This idea that you can’t withhold food and water, that’s a human requirement, but there’s an element of that with the presence of others, that we can’t withhold that either. It’s a balance, though. There is a tension, I think, between the ability to spend time alone and the requirement not to be.

Cinzar: It does feel to me that the book points to the conclusion that people are not meant to be alone?

Reid: Certainly there is solitude to a point, and then it can lose the benefits that it provides. That will be different for everybody. Feelings of loneliness can be productive for certain things, even writing. In some ways I think this book is a little about the process of writing, too. A writer can feel lonely throughout the process and give themselves over to the created world of the story. But at some point they have to finish the book and move on. No one can understand that process or what’s happened for that time, because you’re living it as you’re doing it. It can feel lonely. But you need that time, the solitude. You need to be working. Again, it’s the balance and tension between others and the self.

Cinzar: It seems we live in a culture where it’s easy to be alone and yet feel like you’re not, for example, with all our social media. But in the book you touch on the idea that as a culture there is so much pressure to be happy and yet so many people aren’t. Are the two related?

Reid: Exactly. In a lot of ways, the way culture is modernizing and progressing can perpetuate feelings of loneliness. We haven’t adapted to some of the changes. It seems like people are spending less and less time with each other and more and more time alone. They feel like they are spending time with others, but they’re not. Maybe we will adapt to that, as humans, because that’s the way we evolve, but right now it seems like we have sped up and its happening too quickly. I think that’s the case with an over-reliance on social media. You don’t want to be reductive, because there are a lot of good things about it, but it can be a lonely place. There is very little meaningful give-and-take. It’s more expression and comparison. But it’s not real. As opposed to meeting someone in person, hearing the good and the bad, and trying to work through that, that provides some kind of nourishment for relationships and friendships. It requires more work but you get more out of it. Even when people go to the gym they’ve got their earphones in and it’s about improving themselves but there’s no larger benefit or feeling that you are contributing to a group or something larger. It’s about ‘What can I do to improve myself?’ And this emphasis on how we should be happy all the time, which is a fairly new obsession, is also unreal and no one can achieve it and no one should want to. It’s unattainable. It’s a weird pursuit that heightens the tension and the stress level and everything becomes self-perpetuating.

Cinzar: The book also delves into this idea of the nature of identity, and whether we can ever truly know someone else…

Reid: Or ourselves. Can we ever know ourselves?

Cinzar: Exactly! That was my next question.

Reid: That’s one of those impossible questions to answer. But it’s a good question and one I think about and have thought about for years. And I continue to change my answer. I don’t know if we do. What I do know is we behave differently when we’re alone than when we’re with others. I think that is inherently human.

Cinzar: Do you think we do always behave differently?

Reid: I do. I think we have to. Even when you’re with someone you’re very close to, there always has to be a slight element of performance. And not in a way that indicates a phoniness, there is that sometimes, but it’s just there has to be to allow human interaction to happen. There is a slightly altered person each time. Just slightly. And the way you behave, the things you say, aren’t always the same. So how do we know ourselves if we’re always adapting to each new situation? It’s interesting to think about without coming to a definitive answer.

Cinzar: And so do you also believe, as Jake does, that “all relationships have secrets?”

Reid: Yes, and it’s not even just husband-and-wife but all relationships, between friends, family members. And not inherently malicious secrets, like a husband cheating on his wife. But it goes all the way down the spectrum, to the tiny small almost subconscious secret that isn’t meant to be a withholding of information but it happens when you put things together.

Cinzar: So which secrets are the most pernicious? The little acts we do that no one knows about, or the thoughts we have that we keep to ourselves?

Reid: You could go either way. That’s something that Jake expresses early on. His assumption is that thoughts are purer than actions. We deem actions to be a depiction of reality when in fact we can act any way we want and it doesn’t necessarily reflect how we’re thinking. But according to Jake it’s impossible to fake a thought because if you think a thought, it’s real. As soon as you think it. It doesn’t mean you’re right, but that thought is real.

Cinzar: At one point, Jake and his girlfriend have a discussion about the desire to have someone know them — — really know them. And yet, as we’ve just talked about, everyone has secrets. Is there a contradiction between our need to keep our secrets, and the hope to have someone really know us?

Reid: Good question. A little bit probably. Like so many things in life it’s about finding that balance. But I think there’s something appealing about the idea of trying to get to know someone better than you know anyone else. Especially when there is no biological need to do so, as with your children as an example. But it’s an appealing potential, in a relationship that’s something you decide to do between the two of you, attempt to progress to a point where you know each other better than anyone. But there are situations where it’s not like you’re keeping a hidden life, but the truth in your own brain is the only spot where there’s full access to what you’re thinking. And another person can’t be in your brain in that way. Plus, people change over the course of their life. So, I think you can get to know someone in a way that is still profound and extremely meaningful but never entirely, never fully.

Cinzar: Isn’t that a bit sad?

Reid: It can be. But it can also nice, because it never stops. The fact that you don’t ever [know someone] but you still love them and you have a desire to keep improving and working towards something…what a great thing. What a cool thing to be able to do with someone else. That means something.

About the Author

Ann Cinzar writes about family, culture, and lifestyle. Her work has appeared in a number of publications, including The Washington Post, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Brevity, and The Globe and Mail. Follow her on Twitter and Facebook or read more of her work at www.anncinzar.com.