interviews

Nordic Noir is a Reflection of Modern Europe

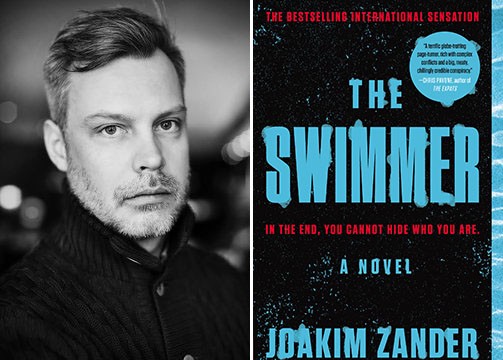

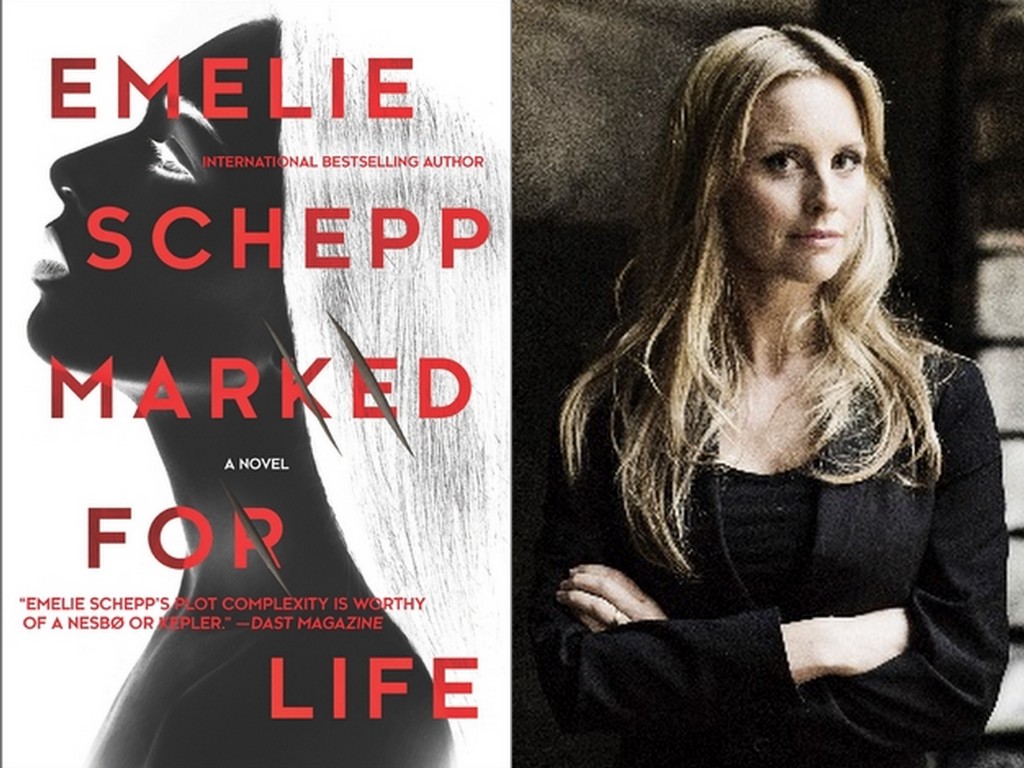

Emelie Schepp & Joakim Zander Discuss Scandinavian Crime Fiction as a Mirror For Evolving European Societies

Nordic crime fiction is a global phenomenon. Tonight, in London, New York, Mumbai, Tokyo, Lagos, Melbourne and Buenos Aires, readers by the thousands will be cracking open books populated by hardened Danish detectives, Swedish hacker-vigilantes and serial killers in Oslo. (Those who prefer their Nordic noir on TV will have more than a few options to choose from, too — The Bridge and The Killing, to name only the most famous.)

When we found out that two of the tradition’s notable and internationally acclaimed authors— Emelie Schepp, author of Vita spår (White Tracks); and Joakim Zander, author of The Swimmer — were corresponding in anticipation of the US release of Schepp’s latest novel, Marked for Life, we were intrigued, to say the least, and eager to share their conversation.

Schepp and Zander talked about what it means to be part of the literary legacy of Sjöwall, Mankell, and Larsson, about their writing influences, and about how they weave issues of immigration, refugees, ISIS, poverty and radicalization into the contemporary nordic landscape.

Joakim Zander: One of the questions I get the most when talking about my books abroad is: “Why is Nordic crime fiction so concerned with societal themes and criticisms?” I think there might be a number of reasons for this; the first relating to the tradition started in the 1970s by the “godparents” of Nordic crime, Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö, who began to publish their books at a kind of breaking point in Swedish 20th century history. Since the beginning of the century there had been a steady increase in economic and societal growth, but the ‘70s meant marked stagnation and societal unrest. It was natural, I think, for crime writers to be drawn to the darker and more overarching themes of those times. This tradition was then carried on by writers like Henning Mankell, Liza Marklund and, to some degree, Stieg Larsson, as Swedish society continued to experience fundamental changes brought on by increased growth, urbanisation and immigration. I think we can perhaps return to the issue of immigration a bit later, but I am curious to hear your thoughts on this, Emelie. Do you feel that your books fit into this tradition of Swedish crime? And if so, why is this the case? Why is this important to you?

Emelie Schepp: As with many other crime writers, my books are a mirror of the world and society I live in. Swedish crime fiction often explores very dark themes and is often greatly concerned with social issues and the problems of living here.

…it can be quite shocking to learn about Sweden as the paradise lost…

Readers obviously feel a fascination for what we might call ‘Nordic melancholy,’ concocted from winter darkness, cold weather, and isolated landscapes. And I do think that my books fit into this tradition. I am aware that readers in other countries have a romantic idea of Sweden as one of the best places to live. It really is a great place to live, but I think it can be quite shocking to learn about Sweden as the paradise lost, and a society where violence, corruption, and murder actually exist. Behind our locked doors anything can happen. My motivation as a writer is to give my view of those who turn to crime, why they do so and what motivates them. I do believe that we are formed by the society we are brought up in. And how about you, Joakim, how do you approach these issues? I am especially curious since your books are perhaps not classic ”nordic noir,” but more international thrillers.

Zander: My whole writing process is quite theme-oriented, and usually I begin with issues that I have been thinking about for a long time. With my first book, The Swimmer, I had been thinking a lot about the war on terror and the West’s complicated and contradictory relationship to the Middle East, and I decided to try to construct part of the narrative to illustrate my view on this. With my second book, The Believer, I had been thinking a lot about how Swedish and other European societies are changing as a consequence of immigration over the last decades, and particularly at the moment with the Syrian refugee crisis. Although the causes that force people to flee their home countries are horrific, I think that the current immigration to Europe is an overwhelmingly positive thing for our societies. It forces us to rethink our old ways, to change and to adapt our societies, something that only makes us stronger. However, the large number of refugees that arrive in a very short time span also pose great challenges. Integration takes time and is often a painful process, especially when the people arriving are often very poor and do not speak the language of the destination country. An unfortunate consequence of this is that some parts of our societies become isolated and excluded from the mainstream. In my view this is a transitory phase, but the problems in these areas are real and tangible.

…some parts of our societies become isolated and excluded from the mainstream…

In my writing I am interested in trying to understand and illustrate where society is at the moment, and right now I think these are the issues define us, so for me it is impossible not to write about it. How about you, Emelie? What are your views on the current refugee situation and is it something that you consider in your writing?

Schepp: In Marked for Life, I wanted to write about a woman who should be odd. But I did not know how odd she was about to be until I read an article about child soldiers. In 2012 there was a huge debate about child soldiers after the movie “Kony 2012” had been shown on Swedish television. The movie is about Joseph R. Kony who is the leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a guerilla group that formerly operated in Uganda. He has been accused by government entities of ordering the abduction of children to become child soldiers. Over 66,000 children became soldiers. As I read the article I remember that I started questioning myself: “What would happen if there were child soldiers in Sweden? And what happens if the solider want to be a child again? Is it even possible?” And where in Sweden could I find children? I know it sounds very strange, but I had to find children that no one would miss, nor search for. To abduct a child in a playground often leads to quite a storm in media and I did not want that. I wanted the abduction to take place in secret, without anyone knowing.

One evening as I watched the news on TV, I saw a truck with a container that had overturned on a highway. And when the police arrived at the scene they found several refugees in the container. They had not been registered at the border. They were illegal. No one knew they were in Sweden. So I went down to the port of Norrköping and looked around. When I saw all the thousands of containers I realized that anything could be hiding in them, including children.

As I began writing Marked for Life I wanted to tell a story of how children can be shaped into something they were not born to become. Children are incredibly loyal, particularly to the hand that feeds them and I understood that such loyalty can be lifelong. I tell a story about immigrant children that are smuggled into Sweden and disappear without a trace. The sad thing is, this actually happens in Sweden today. Because of the large flow of immigration, smuggling and human trafficking are increasing. Desperate people who have decided to flee and have put their lives’ savings toward succeeding won’t be stopped. They have nothing to lose and nothing to return to. They want to achieve their dream of a better future. They will do everything to reach it. Travel down roads that do not exist. On water, through fences, past walls. They risk their lives. Many never make it; they die on the road. Adults and children disappear, are kidnapped, are taken away and are forced into a life of prostitution or slavery. Human traffickers profit from people in peril. And people in peril will do whatever they can to reach their dream. Their motivation is far stronger than that of those who try to stop them. In my second book, Marked for Revenge, I write about the young woman Pim who, in her dream of a better life, agrees to smuggle drugs. In both Marked for Life and Marked for Revenge I write about young people who are forced into different destinies.

And people in peril will do whatever they can to reach their dream.

But you, Joakim, in your second book, The Believer, you write about a young man who choses to join ISIS, although he is in control of his own destiny. Why do you think people in Europe would consider joining such a brutal organization?

Zander: I decided to write a book that partially dealt with the radicalisation of a young Swedish Muslim because, like everybody else, I was horrified by the war in Syria, the quick rise of ISIS, and the reports of young Europeans deciding to join a medieval, brutal form of Islam. In particular I was interested in the mechanisms that make a person prefer such a primitive and violent life to the relative order of Western life. When I started doing research on this topic, ISIS was still in ascendance and not much had been written about the young men (they are predominantly male) who had left for Syria and Iraq. There were very few first hand accounts of the process involved and what they had experienced when they arrived, because many of those in the first wave of jihadists were sent relatively untrained to the battle fields and most of them died there. But I got in touch with Professor Leif Stenberg at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Lund in Sweden and he was extremely helpful to me, taking time to discuss the theology behind radicalisation and sharing case studies.

As I studied the topic more closely, the character that became Fadi in the book came to me. There are many factors that appear motivating for people who eventually become radicalised, but in Fadi I tried to create a kind of composite; a typical case or character. And the typical person is a young man who grows up in a disadvantaged neighbourhood. Often he would have a history of petty crimes and violence before radical Islam made him see the flaws in his old ways.

Almost always the story of radicalization appears to be a story about exclusion.

Almost always the story of radicalization appears to be a story about exclusion. Although there are exceptions, the people who are susceptible are usually not part of what could be considered mainstream society, and do not find that they are welcome there. Radicalization becomes an act of defiance and of solidarity with other Muslims that are oppressed around the globe. It was important to me that Fadi became real to the reader, that his motives were crystal clear. I want the reader to sympathise with and understand Fadi, despite his extremely poor choices.

One final question for you, Emelie: As you are continuing your series about Jana Berzelius, do you think that societal themes, like the current refugee situation, will continue to influence your writing, and if that is the case, how?

Schepp: I have just released my third book in the Jana Berzelius-series in Sweden and I have plans to write several more books about her. My ambition is that my books should reflect Swedish society but that doesn’t mean that I focus on a specific problem. Society can also be mirrored through a character. Our personalities are shaped in a complicated interplay between heritage and environment and it is these factors that I am curious of and want to try to understand. Therefore it is not possible to shut the world out; we are shaped by it and are a part of it. This is how it always will be. Also for the characters in my books.