Craft

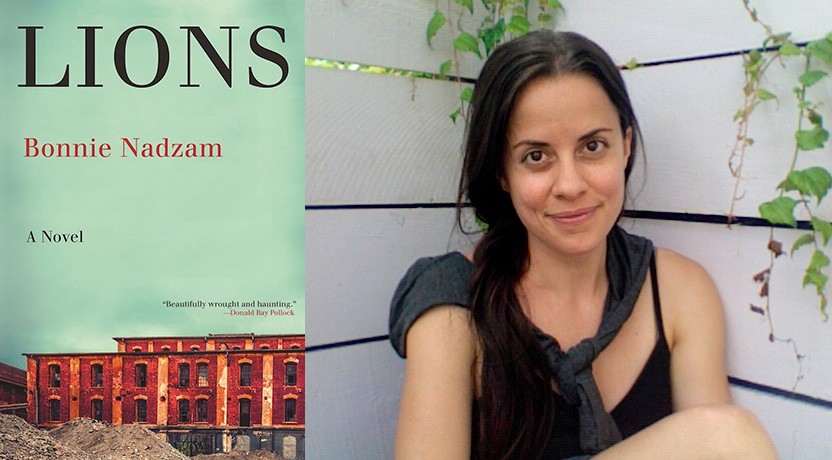

The Failure of Language and A Dream of the West: An Interview with Bonnie Nadzam

Bryan Hurt Interviews the Author of the New Novel, Lions

Bonnie Nadzam is my dear friend and favorite writer. We met in graduate school at the University of Southern California where we studied under T.C. Boyle, Percival Everett, and Aimee Bender, and bonded over too many beers at on-the-beach dive bars in Venice and Santa Monica. I immediately sought out Bonnie’s friendship, not just because she was the most talented writer I’d ever met, but also because I sensed in her a kindred spirit, someone who felt a dis-ease with conventional fiction and who sought to experiment and push against the boundaries of expectation and form. Her stories are often, and alternately, gorgeous, weird, and thrilling, written with a sense of urgency that comes from the sentence-level up, using language that reorients and rejuvenates the reader, both in terms of what’s on the page and what’s in front of them in life.

She’s also a deeply compassionate writer, capable of pushing readers to feel empathy for the most unexpected characters, and asking us to contend with the fact that humanity resides in all of us, even when we’re behaving at our most despicable and worst. Her 2011 novel Lamb is the story of child abduction told, mostly, through the eyes of the abductionist. It’s a thrill ride, a road novel, deeply unsettling, and also deeply moving. It won the Center for Fiction’s Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize, was longlisted for the Bailey’s Prize in the U.K., and was recently adapted into a complicated, nuanced, and stunning film by Ross Partridge.

Nadzam’s second novel, Lions (Grove Press, 2016) is even better and more ambitious than her first. Set in the high plains of Colorado, it’s a ghost story, a love story, a story about stories, and a story about unimaginable sadness and loss. Bonnie and I talked in June 2016 about nonjudgment in fiction, the expectations of readers, writing what you know, ghost stories, and the particular pride of being from Cleveland.

— Bryan Hurt

Bryan Hurt: I thought Lions was so good. It’s expansive, elliptical, and haunting and is as much a story about the West as it is a story about the stories we tell ourselves, the ways we twist and delude ourselves into manipulating reality. But one of the things I admired the most about the book was its sense of generosity. The book isn’t just big, it’s big-hearted. You might be telling a story about how we Americans have led ourselves astray, but at the same time all of your characters sit outside of judgment. Leigh, Gordon, the mysterious drifter. Even if I didn’t agree with them, I felt drawn close to them, and as reality shifts for all of them I felt a great sense of sadness. This is something that I really liked about your first novel, Lamb, too. So I want to ask you about this impulse towards nonjudgment in your fiction. It puts a lot of pressure on readers because you’re not telling us how to feel. We have to make our own assumptions. Is this something that you’re explicitly aware of while you’re writing? It strikes me that making an assumption or a judgment is another way of telling a story and so this might be very empowering to readers. At the same time you might just be giving us a chance to further fool ourselves.

Bonnie Nadzam: Something I have learned about myself alongside writing four novels — two I’ve completely thrown away, two I’ve published — is that knowing a character is as complex a process as knowing myself. Both seem to involve a process of patience and observation, and of allowing space for unexpected things/motivations/behaviors to arise.

I’m sorry to say that I’ve often made choices, taken actions, uttered things… without having a clear understanding of why I was doing so, or of what might be the consequence (though I’m not sure I know anyone in this world who is fundamentally different in this regard). I’ve also discovered that, though for a long time I wanted to believe otherwise, I am not a “good” person. I’m also, however, I think, not a “bad” person. I’m a human being, and that’s a package deal — it involves a full spectrum of behavior. Maybe if I had myself all figured out, the characters I draw would be less ambiguous too. But I think the reality is that a person can always be more self-aware — there is always more about a person to pull out into the daylight; I try to practice this gently both with myself and others (even fictional others, I guess), because once you start rooting around in that shadow, as Carl Jung might call it, there are a lot of surprises. No one is off the hook, no one is above judgment. Curiously, I don’t think anyone is all good, but I do think there are people who are all bad — or at least, we might say more accurately, all “sick.” People who are lost, utterly. Maybe my thinking on this will change. To address the question on a simpler level, stories are predictable to the extent that their characters are predictable, aren’t they?

Finally, I wanted, with Lions in particular, to practice not judging the reader too harshly, either; I did try to make the reader a character in this story, to the extent that the reader is tracking signs and assembling and telling stories alongside everyone else in the book. And everyone is mistaken; and also, by the end, everyone is also peculiarly exactly right.

Hurt: Beautiful answer. To follow up let me ask you about something you and I talk about a lot, and that’s your distrust of “realistic” stories and the complicity and predictability of readers in telling routine or automatic stories — stories that we tell out of a kind of laziness that end up confirming or reaffirming our pre-established sense of the world. But Lions, especially, seems to shake us out of our comfort zones. It’s a realistic story insofar as the domestic, socioeconomic, and problems of the heart are all chillingly present and real. But it’s often told as a fairy tale or a ghost story and eventually becomes something else entirely, something that defies easy categorization. Just when I thought I knew what I was reading and was switching into autopilot, the story took a new turn and I was both made aware of my assumptions and had to throw them out the window. This isn’t a question so much as a long observation, but I’m wondering if you could talk about writing and reading against the grains of expectation.

Nadzam: I’m not sure it’s a good idea to opine on predictable readers when I have a new book out, ha ha, but I will say that something I’ve learned as a reader and scholar myself is that on a first read of anything, it’s a good idea to give the writer the benefit of the doubt, assume the book is well made, and take it for granted that everything in the text is there for a particular reason, even if the reason isn’t obvious to me. On a second read, that’s the place to get critical and inquisitive. And if I don’t have time for a second (or third or fourth read), I’m not likely to write or say anything about the text in question. It’s a way of greeting a text with an open heart — it’s a willingness to be changed by the text. And I wouldn’t love reading if this didn’t happen all the time. Also, readers of my own work never cease to amaze me. The range of responses on the same text — of both Lamb and of Lions — is just fascinating. I always think if a reader picks up on something I didn’t intend, that’s a good sign that I wasn’t steering too hard while writing, but still. It is amazing what some readers see and don’t see. It’s all tremendous fun. I can also say, along similar lines, that it would be no “fun” writing something if I knew where it was going — if the process is defying my own expectations and taking turns I don’t expect, that’s “good” to the extent that I’m not writing to communicate something I believe or think I know, but to dispense with — as much as possible — things I believe or think I know. But that’s probably all stuff we’ve heard before. Regarding a distrust of realistic stories, I of course love reading them. I love as much as the next person being so immersed that I look up from the book and forget who or where I am. But when it comes to writing, it’s just not the right form for me. I love the alphabet, but these lovely and arbitrary marks never fail to communicate what I’m trying to say, or to represent accurately the world of forms I think I’m perceiving (so you see, I don’t trust my limited human perception, either).

I can’t just write fiction as though language were functioning and reliable.

Everything is always slipping, not only the river itself, but these five letters we use to point to the mystery of running water. I can’t just write fiction as though language were functioning and reliable. I also, however, don’t want to write heady philosophical fiction. So that means experimenting to find ways to drop into stories that are as unreliable as the language in which they’re written.

Hurt: So much of your work — your novels and your short stories — is set in the West and deals with a very particular idea of the West: West as ideal, West as fairy tale, West as collective delusion. What draws you to this setting? The idea of this place?

Nadzam: Perhaps, given my resistance to acting as if language works and stories can be reliably told, the American West is the perfect subject matter. Almost no matter what you say about it, it will be a fiction if not a lie. Almost nothing Americans (non-Natives) have said about it from the beginning has amounted to more than destructive stories and lies. And despite the beauty and good friends and wonderful times I’ve had in many places in the West, I find most of it uninhabitable. Especially anywhere in Colorado. Two of my favorite texts on the subject are Wallace Stegner’s The American West as Living Space and Jonathan Raban’s Bad Land. Or you know, something like Bob Drury and Tom Clavin’s The Heart of Everything That Is, which I recommend. Loving and living in the American West is a very complicated proposition if you’re committed to peace and wildness. Also, I’m from Cleveland (which I’ve never written about); I have an outsider’s attraction to and resistance against the West. Somehow that is a source of energy.

Hurt: Why don’t you write about Cleveland? Sorry if this is a silly question but as you know I grew up around Cleveland too. I find myself coming back to it in my own writing, using Cleveland as shorthand for a certain kind of tragic Midwestern-ism. But I’m also pretty proud of my roots, especially in regards to writing. There are so many great writers who are from Cleveland or who have passed through.

Nadzam: The old saying is to write what you know. But in my experience, some things you know too well to say anything about. Writing about Cleveland — I haven’t had the skill for it. It’s like asking me to write a story about my hand, or how my skin feels from the inside, or the quality of my own breath. Add to this that I moved away at age 10, at a time when my parents were young and beautiful and alive and in love; we were surrounded by friends and wonderful neighbors; my mom sang songs as she played the piano; my dad taught us to fish and sand and hammer and paint; we had a huge garden, a swing set, a beautiful two-story deck my dad had built himself, with an iron bell he put up on a post next to a plum tree, which was surrounded by ferns; I shared a bedroom with my two sisters and we had a giant oak tree outside the window, and shelves and shelves of children’s books… so I have this wonderful, magical childhood perfectly preserved in a city I was forced to leave on the edge of adolescence. To top it off, we went from our wonderful, diverse neighborhood to Wheaton, IL, the whitest and most terrifying conservative Evangelical community imaginable. The only thing tragic in my mind about Cleveland is that I had to leave it. All of this said, I’m right now working on a long form story that takes place in Cleveland, on the South Side, where my grandparents are from…

Hurt: I can’t wait to read it. I want to ask a little more about “write what you know” because as I understand it Lamb was very personal. Not that you were abducted as a child, but the main issues of the novel — predation and victimization, innocence and complicity — all hit pretty close to home and draw from your own experiences. Lions strikes me as a pretty personal novel, too. You lived in Colorado, in a former cow town that maybe shouldn’t still be there (and maybe won’t once the craft beer economy goes bust). What makes some experiences more worthwhile for exploring through fiction than others? Why not write a long essay or memoir?

Nadzam: I suppose when I write fiction, it’s because there’s something I feel the need to express that I can’t get at intellectually. Either I’m not ready — as with Lamb — or I don’t know how — as with basically everything — or it’s just not a matter of the intellect. I was arguing with a woman a few years ago about whether or not, if pressed (e.g., if starving to death), we would eat our mothers’ dead bodies. I insisted I would not, even if my mother had told me to eat her as she was passing (imagine we’re abandoned on a ship out at sea, or something like that). This woman I was arguing with was a professional philosopher, and insisted that I had to have “an intelligible reason” for explaining why I wouldn’t eat my own mother’s flesh, when I didn’t necessarily object to eating roadkill, if pressed, or any kind of animal flesh, if pressed. But it seems to me one doesn’t always need intelligible reasons, explanations, or stories, because there is much more to being human than empowering the intellect and engaging the rational mind. My life would be very impoverished, and terrifying, and I’d probably be a psychopath, if all I entailed was intelligible reasoning. Our ability to reason, as humans, is a wonderful tool. But so is hammer, or a knife, and you don’t use either one for everything.

Hurt: In Lions I see you swapping out these “tools” quite frequently, often in the form of embedded narratives: shifting from story to story as told by Leigh and Gordon and the other inhabitants of the town. Most striking, I thought, were the frequent ghost stories that form a sort of connective tissue that holds the many different parts of the novel together. Why did you choose to focus on ghosts and ghost stories? Can you talk in context of the novel’s stunning first line: “If you’ve ever really loved anyone, you know there’s a ghost in everything.”

Nadzam: Well, I can start by saying that when I wrote that first sentence, which was fairly early in the process, I thought I knew what it meant. I don’t anymore. I think “my” process is fairly common and not at all mine — I make discoveries as I go and a lot of early work gets cut as a result, and those elements that don’t get cut are shifted around in a changing context I don’t feel in control of anymore — nor do I understand it. For better or worse, during the process, this sentence remained. Actually, I cut it several times, but it kept coming back. I knew also from the beginning — or sensed, perhaps I should say — that I was exploring around shapes and colors and ideas about the West that I understand to have been there from the earliest days of European exploration. Impressions I had from reading about fur trapping in the 1700s that were somehow the same mood and tone as things I felt myself when I lived out there on the high plains in the 2010, 2011 in an overpriced 1930 bungalow with no furnace and only wood heat… and the more I rooted around in my memory of American history, the more it seemed no matter what time period I landed on — the 1700s, pre-Civil War, the Homestead Act, the Great Depression, the day before when I was for the fourth consecutive day washing the floors with soap and water, sometimes actually with a bandana over my mouth and nose, and thinking things like: “This isn’t the life I signed up for” and “I wish I were in California.” Which as you probably agree is quite a fantasy that would ultimately land me — what’s the idiom? Out of the frying pan and into the fire. It seemed to me that in my life I was repeating a story that was no more than shadowy baggage from the culture I both serve and sometimes despise, and I wanted to pull whatever that was out of my unconsciousness so I could stop perpetuating it.

It seemed to me that in my life I was repeating a story that was no more than shadowy baggage from the culture I both serve and sometimes despise…

So I put the worst of myself into Leigh, and exaggerated her — the vanity, the envy, the longing to be in a better place — and let that play out against a character who embodied — again in the most exaggerated, fictional way — my better instincts.

Hurt: You’re talking about Gordon, right? What’s funny is that in my reading he’s just as selfish as Leigh, maybe even more so.

Nadzam: Huh. It’s interesting that I didn’t specify the character who is embodying better instincts. Yes, I was probably thinking of Gordon. But when I consider who really might be a “foil”, so-to-speak, of Leigh, it’s Boyd, not Gordon. Gordon is a bit of a wild card, an unknown. Though I do find it fascinating that you find him as selfish as Leigh. Just amazing. It gives me this feeling of being in an English class and wanting to argue with you, the texts before us, as if I didn’t write the text myself, as if I didn’t know the answer here, which, as you’ve pointed out, I don’t. What a mystery. The more I write, the more foolish and mistaken intentional fallacies look. I don’t even know what I intended.

Hurt: See that’s what we’ve been talking about — the power and danger of assumptions!

Nadzam: It’s really crazy that I could have created something I have no insight on. It’s so weird.

Hurt: Okay don’t kill me but I want to ask about the titles of your novels: Lamb and then Lions. It seems like you’ve got a theme going. I know the decision to call Lions Lions was somewhat agonizing, and I also fully acknowledge that I was one of the people pushing you in that direction.

Nadzam: My favorite working title for this one was Metalwork, but that didn’t fly with my publishers because, since I’m female, they were afraid people would think it was a book about jewelry-making. Lions was always the name of the fictional town, I think — and I’m not sure why. It felt right. Of course those early homesteaders would have named a town that was more of an idea than a fact after something grand and glorious and God-like but that has never existed there, nor ever could. I saved the document as “Lions” for a while, and went through dozens of alternative titles, but my editor at Grove liked Lions. Personally I still flinch a little when I hear it — Lions after Lamb. Many have asked me if it’s a reference to a passage from Isaiah, but it never consciously was. I suppose it’s appropriate, these books about delusion and misleading storytelling, because to my knowledge, that phrase “the lion lies down with the lamb” never actually occurs in the Bible. Someone out there will have to tell me what all of this means. It there’s a good explanation, I might run with it. Name the next book Young Goat or Fatted Calf.

Hurt: Your first novel, Lamb, was recently made into a movie by the great Ross Partridge (and is streaming now on Amazon Prime) and you also recently published a book of science fiction about climate change, Love in the Anthropocene, that you co-wrote with the environmental philosopher Dale Jamison. Writing is sometimes thought to be lonely work but you seem to thrive on collaboration (and also lack of sleep). Can you talk about the difference between working for years and years on a novel alone and working on a project with a collaborator?

Nadzam: I don’t feel at all like writing is lonely work; going to a party is lonely work! Writing Love in the Anthropocene with Dale was really interesting — on one hand, I moved a lot more quickly through scrapping ideas/passages I loved but that didn’t work, because there was a second person saying very early on: no, this doesn’t work. It was an instant ego-check, which was beautiful because awareness of the ego as an obstacle to love is something we focused on in the Coda, and also because cooperation is one of the “green virtues” Dale recommends in his opus Reason in a Dark Time. It is a characteristic that is almost entirely neglected by ancient and contemporary writers/thinkers on virtue. On the other hand, this sort of process had me walking a fine line between: “you’re right, you’re right” (after years of knowing Dale it’s almost automatic to defer to his experience and wisdom), and “No, I trust my instinct here — I’m right.” Working with Ross on the film was a lot different, because I didn’t really work with him — I loved him the minute I met him and trusted him to do whatever he wanted to with the story, and told him so. It was a privilege to watch him work; he did everything he said he was going to do, and then some. It’s true though that he and I are also working together on something new — it’s just good to work with other people, especially when they’re brighter than you! In my experience though, even with novels and stories there is so much collaboration. With Lions, for example, I had so many long exchanges with good friends — including you of course — about the early drafts. And spoke with my editor, Corinna Barsan, every other day, it seemed, for a while there; my agent Kate Johnson probably read the draft in pieces and in whole a dozen times. And I had some of the most beautiful conversations about belief systems with my father in the days when he was sick and dying, which I incorporated, too.

Hurt: Lions is dedicated to your father and so much of your experience with his long and painful illness resonates throughout it — obligation, grieving, loss. What’s so triumphant and wonderful about the book is that you turn this sometimes painful meditation into something absolutely beautiful, a stunning work of art. Did your father get a chance to read a final draft? What did he think?

Nadzam: What’s really strange is that I began and finished this book, about a father who is a master welder (my father was a master welder) and who dies, and the subsequent tremendous grief, before my father was even ill. It isn’t — as with the novel — that by telling a certain story I incarnated some reality, but that I was always worried about my father’s health, and knew the day had to be coming. Though he didn’t read it in its entirety, I hope he knows that much of the work was an attempt to articulate my love and admiration of him. He read some of it, and helped me with some of it, and was alive long enough to read the epigram, which made him and my mother cry. My father was a true artist, to the bone. In everything he did — designing and building a deck, making a meal, painting or drawing or writing, laying down a bead, or tying flies or designing a room — he had an artist’s eye. And so could sometimes, exasperating everyone, take an excruciatingly long time with even the smallest decisions. When he did a thing, he did it right. He was as much an expert and artistic welder as John Walker (in the novel) — and put all three of his daughters through college before he said it was his turn, and in his fifties, while continuing to work full time for Lincoln Electric, went to college too. He studied English Literature and got a 4.0 at a small liberal arts college (as a very nontraditional student!). I went to a religion class with him once, on campus; I’m so glad I did that. Before he died he gave me his library of books — hundreds of the most beautiful editions of the most beautiful books, and in 10 years he’d read and notated every one of them in his perfect handwriting. In decades of school, without a full time job or sometimes even a part time job, I didn’t read as much. He in fact also published before I did — a story based on a real night in his life when, in 1969, the night Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, he mistakenly brought a black friend, Lenny, to Fat Molly’s (now Cafe Isabella’s) in Little Italy, in Cleveland. To spare Lenny’s life he took a beating by a circle of men in their undershirts, wielding baseball bats — my dad was curled up against chain link fence, I can’t think of it without tears in my eyes — and spent days in the hospital. It was a life-changing, traumatizing event. Lenny was sick with cancer the same year my dad was. It was a hard, hard year — I still have a difficult time with memories of it, heart-stopping memories. I was there with my mother, and holding my father’s hand, as he took his last breath and gave his life back to the universe. He loved this world. I love and miss him terribly. More all the time. It’s incredible to me that loss on such a level is happening all the time, every day, every minute, to every one of us.

About the Interviewer

Bryan Hurt is the author of Everyone Wants to Be Ambassador to France (Starcherone) and editor of Watchlist: 32 Stories by Persons of Interest (Catapult). His fiction and essays have appeared in The American Reader, Guernica, the Kenyon Review, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Tin House, TriQuarterly, and many other publications. He lives in Columbus, OH with his family and teaches creative writing at Capital University.