interviews

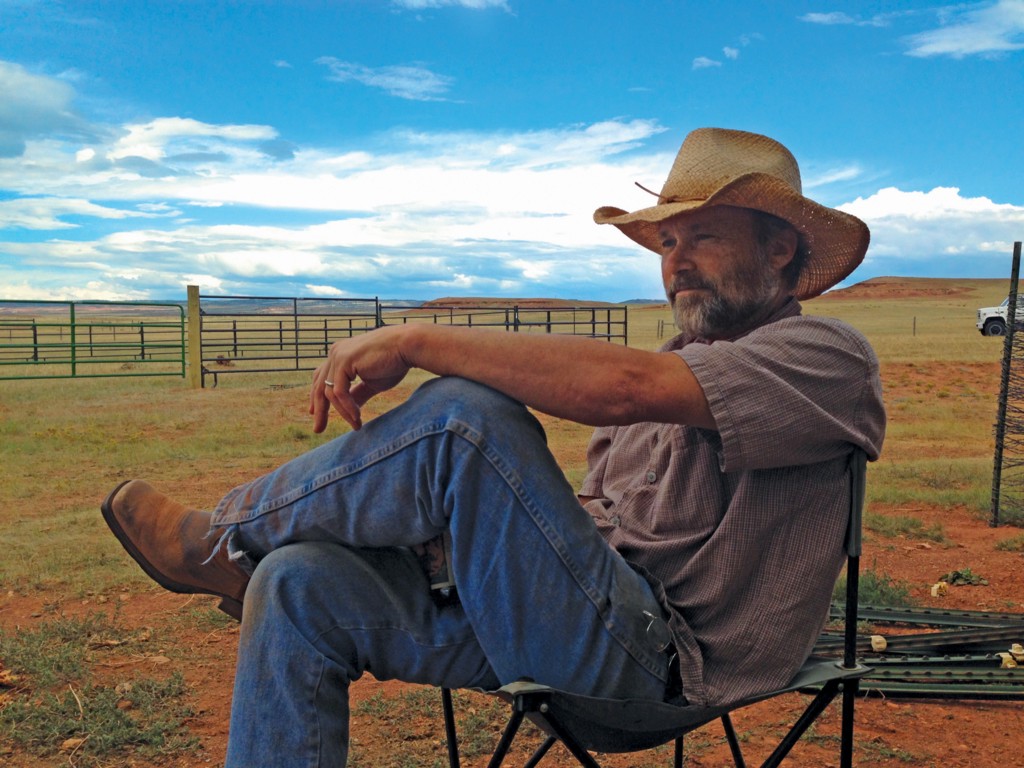

Brad Watson on Scoundrels, Medical Mysteries & Building His New Novel out of a Family Secret

by Matthew Neill Null

I first read Brad Watson’s debut Last Days of the Dog-Men while riding in a screaming box (the DC Metro), wearing an outlet mall tie. The book, full of men and women at the end of their tether, was a welcome counterpoint to the scene at hand, with long musical lines of prose that were just as lush and image-rich as the hot green Mississippi they described. A shining book. I was happy to open the newly-released Miss Jane (W.W. Norton & Co, 2016) and find the qualities I’ve long admired in Watson’s work. The novel is the story of Miss Jane Chisolm, “born in rural, early-twentieth century Mississippi with a genital birth defect that would stand in the way of the central ‘uses’ for a woman in that time and place — namely, sex and marriage,” according to the jacket copy. The novel traces her long life on the margins of that society, where neighbors whisper about her condition but never speak of it directly. In that silence she cultivates — is forced to cultivate? — a rich inner life.

The central paradox, for me, is that Miss Jane is surrounded by the fecund, sexualized natural world of her parents’ farm, a pageant of birth and death, as when she discovers a tomato worm eating her best plant in this stunning passage: “The worm’s fat, segmented body was studded with the rows of pure white cocoons that had grown from wasp eggs laid under its skin. They looked like embedded teardrop pearls or beautiful tiny onion bulbs growing out of its bright green skin. Inside the cocoons, wasp larvae sucked away the worm’s soft tissue as casually as a child drawing malt through a straw. The worm seemed entirely unperturbed. No doubt a tomato worm is born expecting this particular method of slow death, a part of the pattern of its making somehow, something its brain or nerve center, whatever it has, is naturally conditioned to recognize and accept. Just as a person hardly registers, until near the end, the long slow decadence of death.”

In addition to Miss Jane, Brad Watson is also the author of the novel The Heaven of Mercury, a finalist for the National Book Award, and two collections of stories: Last Days of the Dog-Men, winner of the Sue Kaufman Award for First Fiction from the American Academy of Arts & Letters, and Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives, a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award. His short fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, Granta, Oxford American, and Ecotone, among other journals. A two-time winner of the O. Henry Award, he teaches creative writing at the University of Wyoming.

— Matthew Neill Null

Matthew Neill Null: As a fellow product of rural WASPs, I still struggle to understand why we were so tight-lipped about sex — like Miss Jane, my first inkling came from seeing animals fuck, a common farm occurrence, though you got hushed for pointing it out. I would guess that many people of Miss Jane’s era, both male and female, would describe her as “chaste” (their compliment) or “barren” (their pejorative), but she has an erotic inner life, she masturbates, she fantasizes, she falls in love. I love that balance of external silence and internal symphony. Could you speak to this aspect of creating the character? Was it there in the first draft, or did it develop over time?

Brad Watson: My introduction was my neighborhood’s alpha dog, a big collie named Lonesome, and a tiny little mutt named Honey. He curled over that little dog in a way that was fascinating and obscene. All the lesser dogs stood around them in a circle, watching mournfully, and all the children stood around behind the dogs, in some state of enrapture, I suppose.

This book went through more than the usual number of drafts. I began with a dual story, first-person of a man in the present, who tells the story of his great-aunt, Jane. There was something in that guy’s narration, his story, but it did not belong in Miss Jane. Truth is, I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to fully imagine this character, Jane Chisolm, so I was looking for a prop of some kind. Cowardice never gets a novel written.

Cowardice never gets a novel written.

Everything that’s in the novel developed over time. Everyone says first and even early drafts are awful, but the problem with mine, this time, was just how far off the mark they were, how far they fell short of realizing the character Jane. I had to keep turning it on again, recycling my imagination, layering things in (even while I kept throwing a lot out). It was like a very slowly developing photographic world and person. I’d re-read a scene, a moment, and try, like a painter I suppose is the better analogy, to add just the thing that would make it richer, more real in the mind. She, Jane, was very hard for me to get at. A life and mind hard for me to imagine. And so it just required a lot of patience and tenacity, a willingness to start over more times than you’d like.

MNN: Jane is partly inspired by your great-aunt’s medical condition. I’m curious, did your family speak openly about this? Or did you have to piece it together? You mentioned doing an incredible amount of urological detective work.

BW: No one still living knew anything specific about the nature of my aunt’s condition beyond her incontinence. And then, before the real Jane died (one of my clues to work with was that Great-Aunt Jane lived a long and, under the circumstances, healthy life, from 1888–1975), my mom’s sister got it out of her that she had just one opening — for everything, it seemed. But you’re right in assuming that they really just didn’t talk about it. In those days, especially among Southerners, especially among Southern country folk, you did not talk about such private matters. It would have been disrespectful. They loved Aunt Jane and were not ashamed of her, nor was she apparently ashamed of herself — though I wondered how much of that was the family’s tendency toward stoicism.

I talked to my great-aunt’s oldest surviving nephew, who was by then old and in bad shape (and, ironically, in Depends and a tee shirt, in a trailer home under which two dogs were shaking the whole dwelling with their blissfully ironic humping) and all he could say was, Well, yes, Aunt Jane had a problem. I could find no medical records (they destroy them after a certain number of years, or used to, anyway). The nursing home she’d lived her last years in was gone. I combed through Dr. Hugh Young’s pioneering 1937 book, Genital Abnormalities, Hermaphrodism & Related Adrenal Diseases, a 600-plus-page tome with all hundreds of images of bodies and body parts and genital abnormality close-ups and drawings of dissections and surgeries and logs, etc., but nothing seemed to echo my aunt’s condition. It possibly sounded like “vaginal agenesis with cloacal anomaly.” That did not work out. There were other conditions with a single opening, but they involved complications that my aunt seemed not to have suffered. It was a long process of considering various conditions and discounting them before I finally saw something on “persistent cloaca.” Very little research on it for the longest time because of its rareness: something like one in 20,000–25,000 births. So Young probably had not even seen a case of it. I found it on the web, and given that a) there is incontinence, hard to repair, and b) it is possible to endure it without a constant infection(s), and c) there was no real ability to repair the condition surgically until several years after my aunt died, I thought, “This must be it.” The one urologist I got to talk to me didn’t know anything about it, said I’d need to talk to a pediatric urologist. I talked instead to a student’s father, an OB-GYN, an energetic guy who often collaborates with various colleagues in surgery, and he knew about it, and confirmed some things I wasn’t sure about, being an amateur net-surfer pretty confused, by that time, over the incredible variety of ways the urological system can go awry from the “normal” in the process of bodily formation. I could not really imagine Jane’s story until I could be reasonably certain of what her condition was. And that’s just one reason it took me a long time to figure out what, in the end, is a pretty simple book. Other things I knew that helped imagine a fictional Jane were the real Jane’s extremely thin physique — which helped me to imagine the parts about her habit of starving and dehydrating herself in order to be “safe” in public — and a tidbit an older cousin gave me late in the game: Jane took to wearing several petticoats beneath her skirts, and a little bit of perfume, in what was no doubt a futile effort to disguise the scent of a urological “accident.” And my mother remembered that, as children, they had giggled because Aunt Jane “squeaked when she walked,” because she had to wear rubber undergarments over her diapers.

Why the hell did I decide to write this book? I was fascinated by my great-aunt’s “secret.”

Why the hell did I decide to write this book? I was fascinated by my great-aunt’s “secret.” And, I thought, no one else is going to write it. She must have lived an extraordinary life (she did get out, and often traveled by bus to see her siblings and nieces and nephews who’d moved to east Texas), and she was very much on the verge of being forgotten. She was a family legend, a mysterious one, and — I thought — a noble character. That’s how I got caught up in the idea of writing a novel about her. I didn’t know what I was getting into.

MNN: I’ve always admired that, in a world obsessed with “likeable” characters, you aren’t afraid to write about scoundrels. Miss Jane’s father is a taciturn drinker, and her mother is a scold and a bit “flighty” as we’d say in West Virginia, but my favorite is her older sister Grace, who is sexually malevolent in such a marvelous way. Without giving away too much of the book, I will say she uses sex as a bargaining chip, all while throwing it in the face of a sister who is denied access to the erotic world that is such a part of the human experience. So Brad, do you have any practical advice for those of us who want to write about scoundrels? What do you tell your rising talents out in Wyoming?

BW: One of the difficulties I faced as a newspaper reporter (beyond the fact that my professional competence was minimal — I wrote well, but had little real training as a journalist) was the degree of empathy I carried into any story involving people who appeared to be crooks or scoundrels. I didn’t like the idea of ruining someone’s life if I couldn’t be one hundred and ten percent sure of my case. Of course, some people were so obviously (not at all subjective, there, right?) slime-balls that it felt good to uncover their misbehavior or criminal activity. But other people were apparently just people who screwed up, made a mistake, a poor judgment, or reacted to a situation improperly out of fear or incomprehension. I had newsroom colleagues who were ready to nail anyone who got into trouble. There was an uncomfortable level of self-righteousness, in some cases, it seemed to me. Unlike them, I had not come roaring into journalism with a beat-up copy of All the President’s Men bound over my heart with duct tape. I had come from a frigging MFA program in creative writing, for Christ sake. Writing fiction, in terms of dealing with your characters, is all about empathy. All about figuring out this or that person’s humanity, her or his human-ness. A scoundrel in fiction had better be just as interesting if not more interesting than the good folks. A scoundrel might believe she has very good reason for her actions. She or he had better be a complex character who can’t be summed up in the simple language of good versus evil. If you don’t understand that, you should be writing propaganda for some extremist group or another. You shouldn’t be writing fiction. You shouldn’t be your newspaper’s crime reporter. A writer friend has said that the notion of a writer loving or even liking her characters is ridiculous. It’s not at all about them being likeable or loveable. It’s about whether or not they’re interesting. So, in short, your scoundrels should be among your most interesting characters. They, like inherently good people, face the greatest risk of being oversimplified, two-dimensional, unrealistic, sentimental, or laughably sinister creatures.

MNN: You have an epigraph from the phenomenal Swedish writer Lars Gustafsson, and I feel I detect a strain of Gustafsson in here, particularly in the opening pages, which are just this phenomenal willing up of a world — a corrective to anyone who thinks exposition hinders narrative. I’m thinking of this passage: “You would not think someone so afflicted would or could be cheerful, not prone to melancholy or the miseries. Early on she acquired ways of dealing with her life, with life in general. And as she grew older it became evident that she feared almost nothing — perhaps only horses and something she couldn’t quite name, a strange presence of danger not quite or not really a part of the world.” You make a statement, then qualify it, with “perhaps only horses” and similar emendations, like you’re going back to darn a stitch. Her inner life is given nuance, complication. Out of curiosity, I went back to your 1996 debut, Last Days of the Dog-Men, and found the different style I remembered: these swaggering, musical, image-rich sentences that remind me of Barry Hannah (who said of your work, “Only the Irish geniuses wrote like this,” a blurb to beat all blurbs), with more of a focus on the outside world. While the old music is still here in Miss Jane, there’s more of a meditative quality to your prose, exploring the inner emotional topography of your characters. Do you see this evolution yourself? Or am I making it up?

BW: First, I suppose you can get away with expository writing in something that is, effectively, a prologue. So I took advantage.

I re-read that amazing short story by Lars Gustafsson [“Greatness Strikes Where It Pleases” from Stories of Happy People] more than once while I was working on Miss Jane, hoping to capture at least something like the cool wonder and patience that works so powerfully for Gustafsson there and in other works of his. I thought it appropriate, also, to study that story for the way in which Gustafsson manages to write about a character who is essentially inaccessible to most (if not all) of us — a great, beautiful mystery of a human being who eventually finds his own version of greatness. Of course my character is not nearly so closed off from the world, from “reality” as most of us know it, as is the boy-then-man in “Greatness.” But it served as much-needed inspiration, in that I tried to learn from his ability to get at that deeply profound sense of (in his case) inarticulate wonder.

As for the prose in this book — yes, I did not want to write a book that indulged so much in stylistic flourishes as my previous work (although I’d already begun to draw back from that a bit in Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives). Not only was I a little tired of that voice, that self-indulgent fun, I also did not think it appropriate for this story. I thought Jane should be center-stage, and that the language should only support her, not embellish her. I wanted whatever strangeness there is there to come from Jane’s condition, her awareness of it, not from forcing the language. At one point, my editor (and my agent) said I was holding back too much, so I loosened up a bit. But I was cautious, even then. I didn’t want to muck up the reader’s sense of Jane. I wanted there to be as clean a sense of her on the page as possible.

MNN: Much of the book hinges on Jane’s lifelong friendship with Dr. Thompson, the traveling country doctor who delivered her and discovered her condition, a bond perhaps informed by his own status as an outsider in that place as a highly-educated and childless widower. Could you talk about the genesis of that character? While reading the novel, I kept thinking of William Carlos Williams’s fabulous and overlooked story “Old Doc Rivers,” about a drug-addicted country doctor of great skill and great unpredictability, so I was pleasantly surprised to see you mention that story in the acknowledgements.

BW: In earlier drafts he was different, physically and temperamentally. In fact, he was a lot more like Old Doc Rivers than now. I can’t recall when I read the Williams story but it was early-on enough that Thompson had a more rascally side and leaned more heavily on the cocaine and drink than the man he turned out to be. I wanted Dr. Thompson to be kind of romantically mysterious, I guess — and handsome in a refined sort of way — and started to work on another figure in my head. Since I’d once met Dr. E.O. Wilson, and was so in awe of him, admiring him as a person as well as a scientist and writer, he (or my impression of him from c. 1988 and his public persona) found his way into being a kind of very basic model for my doctor. So you can see there was quite a transformation from the original portly, bearded, rather boisterous figure into the more genial man with a sly sense of humor and a great capacity for empathy and love for his fellow human beings — as well as birds, especially his peacocks.

MNN: You’re a master of writing hell-raising children. I’m not only thinking of Grace Chisolm, but of the roving brothers in stories like “Eykelboom” and “Vacuum,” which first appeared in the New Yorker. Were you a hell-raising child? Or do you have them? I sense hard-won knowledge.

BW: It’s funny, because when I was the age of the boys in those two stories, I was “the good boy,” just like the middle brother in the stories. But in the South when and where I grew up, being timid (as a boy) was suspect, as if you might not be “all boy.” My older brother was an anti-authority hell-raiser from the get-go, and my younger brother was plain trouble. And there I was, the middle brother, a goody-goody. My older brother teased me about it. Others teased me. I very much admired tough kids, and wanted to be one. So, I determined to change, to get tough, to transform myself from the pale, timid weakling into something else. I did it with a vengeance, first with honest sports, and soon enough with cars, alcohol, violence, trouble with the police (arrests) — being an all-around wanna-be-asshole who secretly had a good heart. Being sensitive was not safe. So, yeah, I ended up married between junior and senior years of high school, out on my own with a family. It was an extended rebellion that did not end well, although all is well enough with that, now. That is to say, we all survived it. But I deal with the effects or consequences, even now, and enough said on that.

MNN: Could you imagine your aunt reading this book?

BW: First, I don’t know if my great-aunt was a reader, or not. Although I suspect, for some reason, that she was not much of one. Maybe that’s because most people on that side of my family, in the generation before mine, were not big readers as far as I know. Second, given her time and place (Mississippi, 1888–1975 — my Jane Chisolm was born later, in 1915), what and where she came from, it might’ve horrified her. But I like to think that whatever is left of her in the world, physical or metaphysical, would absorb it now in the spirit it was intended. A song of praise and admiration — and of wonder, as well.

About the Interviewer

Matthew Neill Null is a writer from West Virginia, a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and a winner of the O. Henry Award, the Mary McCarthy Prize, and the Joseph Brodsky Rome Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He is author of the novel Honey from the Lion (Lookout Books) and the story collection Allegheny Front (Sarabande). Next year he’ll be in residence at the American Academy in Rome.